Sudip Bhattacharya analyzes the multiracial voting bloc that has coalesced behind the Democratic Party under the umbrella term ‘People of Color,’ arguing that this coalition, rather than organically producing a socialist politics, must be actively courted by socialists from these communities.

Introduction

In his bid for the governorship of California in the late ‘60s, Ronald Wilson Reagan (6-6-6), the godfather of Trumpism, gathered significant support from Mexican Americans, as well as some Asian Americans, across parts of the state. Of course, the major base of his constituency were paranoid whites and those who had become part of the “middle class,” but according to historian Mark Brilliant, Reagan managed to win just enough votes from Latinx and Asian Americans to land him the coveted governor position of one of the most important states in the country, providing him with a launching-pad for national stardom and notoriety.

Reagan, unlike some other conservatives, accurately recognized some of the simmering tensions and differences among and between various groups of color, especially Latinx and Asian.

“They’re Republicans, they just don’t know it yet,” he would later say once in the White House, regarding Latino voters.

At the time, there were a number of Latinxs migrating to the U.S., or who had been in the country for decades (for some, multiple generations) who did associate success with achieving the American Dream. Some, as would be the case up until the 2000s, believed that hard work led to material successes. Some would flee parts of Latin America, areas twisted into dysfunction by U.S. support for coup governments and right-wing demagogues. For many, all they saw was the promise of America versus the “corruption” at home.

For some Asian Americans, it was anti-communism that drove them into the arms of Uncle Sam. For others, it was their own class interests and aspirations that had them convinced that what impacted African Americans and some Latinxs would not affect them as much. In a few instances, this was to be the case, as some Asians would find it somewhat easier to climb up the ranks of the economically mobile and privileged versus the shut doors that more African Americans would come across in their own attempts at maintaining some financial security in the midst of neoliberal decay and Reaganism.

This dynamic has changed significantly in the past ten to fifteen years. For a decade or so, especially since Obama, a majority of Asians, Latinx, and African Americans now align on partisanship and some social issues. In the 2020 presidential election, over 60 percent of Latinos and Asian Americans, according to a Vox poll, along with 90 percent of African Americans voted for Scranton Joe and the Democrats, a party to the left of white nationalism and extremist capitalist hubris (low bar but nevertheless…).

With the explicit racist nature of the GOP and modern conservatism, included in this dynamic are Confederates and those who believe whites are being “replaced” (the irony considering the history of colonialism), it’s understandable how a growing number of Asian and Latinx Americans have joined African Americans under the Democratic Party’s umbrella. The extremism of the right wing and their failed economic policies have also made it far more stark in terms of what people lack and need in modern U.S. society, such as universal healthcare.

It’s clear something has been going on in terms of groups who would be defined as “people of color” or as “non-white” that could possibly shift U.S. politics significantly. Some, liberals and leftists alike, such as popular writer Steve Philips, have argued that this new emergency-based non-white alignment suggests a new coalition is on its way, and with the white population declining, exemplifies a more progressive trend. This is true to some extent, given that most “people of color” share similar experiences which would leave them more open to discussions regarding systemic injustices. But as much as various segments of various groups now find themselves under the Democrat party umbrella, it’s also true that this new potential “realignment” has some serious limitations.

After all, Trump is no longer in office. Bidenism instead has been dominant, encouraging people to not think beyond preserving our capitalist institutions, perhaps “reforming” them along the way. Indeed, there have been some types of “improvement” within the machinations of the machine, such as a more favorable National Relations Labor Board. Overall, the frustrations that existed prior to Biden’s run persist, the contradictory nature of being a working class person of color, someone who no longer needs to fear the explicitness of a leader such as Trump, all the while still finding themselves working two jobs to maintain a shitty apartment in a suburban outskirt.

Accordingly, you now have Asian American and Latinx voters once more slipping away from politics entirely, or expressing support for conservative candidates in major cities and towns. Even among African Americans, there is volatility and schisms. For instance, while most African Americans desire a change to our so-called justice system (a Biden campaign promise), many have also expressed support for police funding to stay the same, or to even be increased.

Kiana Nox and Khadijah Edwards write, “Similar shares of Black Democrats and Republicans say that funding should increase (36% and 37%, respectively), stay the same (40% each) or decrease (24% and 21%).”

Eric Adams, the “centrist” Democrat mayor of New York City, won his race by gaining the support of working class black and brown voters with pro-”law and order” rhetoric.

Clearly, some things have changed, but it is presumptuous to suggest that Asian Americans, Latinxs, and African Americans now constitute a pro-socialist constituency. If anything, a conservative or anti-socialist Democrat politics may be on the horizon instead, unless of course, we, especially as socialists of color, take the role of leadership more seriously and contend with ideas spewed out from Democratic Party members and their so-called “friends” in the communities we’re in.

Whither The “Person of Color”?

Efren Perez, political scientist at the University of California, has focused his research on the topic of “poc” and potential coalitional politics among segments of Asian Americans, Latinxs, and African Americans. Through in-depth interviews and surveys of various groups in the Los Angeles area, Perez has noted that most Asians, Latinxs (nearly sixty percent each), and African Americans (ninety percent) identify with the label of being a “person of color.”

Those who identify with the label cited the increasing prejudice and explicit racism exemplified in modern U.S. politics as a major reason for why.

“In other words, in the presence of prejudice or discrimination toward one’s racial in-group, Blacks become more pro-Black, Latinos become more pro-Latino, and Asians becoming more pro-Asian—not, as my intuition about PoC ID implies, more favorably disposed toward people of color writ large” Perez states in Diversity’s Child: People of Color and the Politics of Identity (26).

Characters like Reagan were racist themselves, personally and through policy. However, much of the focus on distracting white voters with paranoia over the Other would be targeted at African Americans, and done so sometimes in a thinly veiled manner. For instance, Reagan, without ever stating he was pro-segregation, still managed to get his message across to white voters in the south that he did believe in an old way of living and controlling people by visiting areas like Philadelphia, Mississippi, and speaking on “states’ rights.” At the same time, he did expand on some forms of amnesty for immigrants, Asian and Latinx, all the while funding right-wing regimes and terrorists that would destabilize the regions such groups heralded from.

George W. Bush himself spoke of “compassionate conservatism” and immigration reform. His bastardized Spanish, however cringe-inducing, was an appeal to Latinx voters at least. Again, the policies these two put forward were destructive, and one could argue far more destructive than Trump to a degree. After all, Bush and his acolytes invaded Iraq, a country that had nothing to do with 9/11, leading to decades of bloodshed and a collapse of government institutions and resources. To this day, many Iraqis are left to fend for themselves, while private contractors reap profits, and Iraqi politicians bloviate.

However, those same extreme reactionary elements, the Pat Buchanans and the like, those who speak of a “civilizational war” on the whites and a “southern invasion,” have become far more emboldened within the GOP and mainstream politics. The explicit racist rhetoric has become far more “accepted” and spread, in the dungeons of Congress and in the green rooms of Fox News. A rabid constituency now rears its head, chomping at the bit, eager to push forward candidates like a Trump, who would find it natural to refer to Covid-19 as the “China virus,” to suggest that all Mexicans are “foreign” and “rapists,” and who, even while seeking to attract a more diverse voting base, consistently referred to African Americans as “the blacks” and still believed Frederick Douglas was still around (if only).

Such rhetoric and buffoonery has pushed Asian and Latinx populations, or at least in certain corners of the country, to align more so with African Americans. This includes not only aligning at the ballot box, but also, when it’s in terms of thinking about coalitional politics and the need for it.

“I think saying a person of color is a bit more empowering compared to the term minority just because I think minority seems very isolating…I feel like person of color, you imagine more groups with you,” an Asian American respondent explained to Perez.

I’ve experienced this shift too, when speaking to family and friends. It was 9/11 and its aftermath that would reinforce among South Asians and some Arabs I knew personally that our fates were intertwined with other groups, especially African Americans. Indeed, South Asians, Indian Americans in particular, would prove to be a major constituency supporting Obama in his two terms in office.

During the Floyd uprisings, it was noted by various outlets the cross-racial support the unrest and resistance against police brutality did receive. This did include some whites, as well as Latinxs and Asians. In talking to friends of mine, all of us could connect our own experiences as non-black POC to the broader feelings of being marginalized or oppressed. The protests represented a broader resistance against Trumpism and reactionary elements.

The “poc” identity, therefore, reflects a positive direction toward groups identifying a shared set of issues and enemies.

Of course, this is not a new phenomenon. Du Bois, even prior to his political evolution as a communist, spoke of a global “color line,” in which Chinese, Indians, Africans and African Americans were united in their need to overthrow European and later, U.S. hegemony. Similarly, despite being maligned (by people who don’t read him accurately) as somehow parochial, Malcolm X had always been a proponent of various groups of nonwhite people, or colonized peoples, to see themselves in the others’ struggles. In fact, Malcolm X would consistently refer to the successes of colonized peoples abroad, such as the Viet Minh against the French, as examples to follow for African Americans. He would correlate French power to white supremacy in the U.S.

“Up in French Indochina, those little peasants, rice-growers, took on the might of the French army and ran all the Frenchmen, you remember Dien Bien Phu!” he exclaimed in his “Ballot or the Bullet” speech, adding, “The same thing happened in Algeria, in Africa.”

What’s different now is that some of this truth, this objective reality of people of color or non-Anglo people sharing some common issues and opposition, has become more accepted, or known. The Trump administration revealed how many explicitly white supremacists and racist forces do exist, despite the thin veneer of “civility” that emerged in the 1990s and stayed with us up until Obama’s final term in the White House. When you have men and women in the streets, waving Confederate flags, and a man with immense power calling countries in the Global South “shithole” countries, and suggesting that border police shoot immigrants along the U.S.-Mexican border in the legs, it’s difficult to ignore. For many Asians, the anti-Asian hate wave, precipitated by Trump’s rhetoric, had created an atmosphere of angst and anxiety, provoking many to vote for the first time, desperate for “stability.” It was the same for Muslims broadly and other groups who had been an explicit target of Trump’s racist drama.

Still, the “poc” identification, as much as it’s been a sign of people realizing some form of commonality, is also very much tied to partisanship rather than principles or values regarding how society should look like. For some, including those interviewed by Perez, many viewed being authentically “poc” as people who vote Democrat. Now, what that means is up for debate.

So far, we’ve seen various groups in various regions pick and choose different types of Democrat, from conservative to progressive, from those who’ve been in power for decades now, to others who are more upstart and challenging. The “poc” label is a sign that people are open to engaging with others, are open to solidarity and other forms of broader struggle. Yet, it is also not a substitute for building a pro-socialist constituency, which is still necessary if we are to win power and win a society that’s beneficial for most people of color existing within it.

In a sense, the alignment has been mostly restricted to voting Democrat nationally or to vote against the most extreme totems of Republican governance. Beyond this, political coherence and solidarity is still something that needs to be analyzed and developed with intention and drive by socialist organizations and leadership.

The Nonwhite Coalition Is Nigh

Over the past several decades, opposition to injustice has often been channeled through the Democratic Party. Opposition to explicit forms of racism to vague notions of fairness and inclusion have become intertwined with Democratic Party branding, or the very least, dissociated from the Grand Old Party and its various shades of old cranky white men and white women.

As co-founder of the Black Agenda Report and one of the few prominent voices on the left warning against the rise of Obama early on, Glen Ford had accurately presented the political capture of African American politics to the Democratic party establishment.

African Americans have been, for the majority of U.S. history, one of the more progressive forces in the country, especially when compared to their white counterparts. However, following the crushing of the New Left and the missteps of labor unions (which included conservative leadership AND membership purging left-wing organizers), a void had opened up by the late 1970s, right around the time of Reagan’s rise.

The Democrats too were now sliding away from New Deal and Great Society programs, producing a cynical brew of kinder and gentler forms of capitalist interest-groups as well as beaten down and sometimes, delusional labor leaders. Eventually, this too would uplift candidates such as Bill Clinton, who would appeal to some black voters all the while proving his bona fides as a “new” type of Democratic politician, one who had no problem scapegoating poor and working class people of color like his predecessors had done, and someone eager for such things as “welfare reform”, which really ended up being tossing poor people aside, compelling them to work for less than minimum wage to receive paltry social benefits.

“Democratic Party politics kills Black politics”, Glen Ford would state, time and again. Inevitably, seeing no alternative, many African Americans who are registered would vote Democrat, despite an economic agenda pushed by Clinton, Gore, and later, Obama, that cut against their collective economic interests.

Over time, a network of pro-Democrat community organizations and leaders would spread instead, reinforcing the idea that a politics of liberation and improvement could indeed take place through reforms and electing figures such as Obama, and now, Biden.

Ford himself explained:

The Democratic Party is hegemonic in Black America. I’m not just talking about the fact that Black elected officials are overwhelmingly Democratic. The mainline Black civic organizations—the NAACP, the Urban League, and the rest—are annexes of the Democratic Party. So are most Black churches. The party’s tentacles even reach down to the Black sororities and fraternities.

Some of this is also being generated across Latinx and Asian American communities, especially since Obama’s time in office. Once again, for many, there’s a stark choice between electing someone antagonistic to immigrants of color and to anyone who isn’t a particular brand of race and religion, and picking someone who is somewhat less destructive and can at least, exemplify some notion of astute leadership. Indeed, when we look at the 2020 presidential election, and in states like Georgia, where senate seats were up for grabs, it would be Asian Americans and sometimes, Latinxs that swung the election in favor of Democrats even in areas that are seen as typically Republican.

In my home state of New Jersey, you have emergent South Asian American lawmakers and organizations that throw their support behind the Democratic Party. Once more, this is understandable given the existing alternatives. However, as I’ve also seen, the state Democratic Party is very much centered around maintaining a pro-business ecosystem. Sometimes, this may lead to some wage increases, albeit incremental. Yet, overall, as the Democratic Party is currently conceived, there will not be progressive, and certainly no socialist policies being pushed. In the end, the party attracts people of color, and develops relationships with members of the Desi community who have the ability to fund their campaigns.

Yet, the need for socialism, for an economy run for the interests of most working people, has only become increasingly necessary. Clintonite half-measures, if you call them such, are no longer able to justify themselves, nor meet even the basic needs of people of color who’ve climbed their way into the vaunted “middle class.” The grand bargain that was made, implicitly like the rest of liberal social contract history, whereby some working people, including people of color, were fine with living and working in white-collar professions, with some form of pension, higher pay, and lush green lawns to gush over with friends, in exchange for navigating a social world where unions don’t exist, where healthcare and housing remain privatized. Now, it’s been forty plus years of neoliberal “reform,” of gutting the social welfare net and shaping society for the wellbeing and self esteem of major corporations, and society overall is now facing internal cleavages, and erosion.

For most people of color who work for a living, whether behind a desk all day or standing on their feet and smiling for consumers buying another six pack and some garam masala, society under capitalism is untenable. Not only were Great Society programs stripped away, we now have less social mobility than in decades past, along with increasing costs of living eating away at whatever minimal financial progress one could try to make.

“Despite working more on average than whites, Latinx families have far less household wealth,” Danyelle Solomon, senior director of Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center for American Progress, stated in a recent report focused on Latinx American issues and economic status.

Asian Americans, currently, have the widest gap in terms of wealth/income within the group, a direct product of neoliberalism as well as Asians arriving to the states with not much at their disposal. Overall, in many cities, including New York City, Asians constitute a high percentage of those languishing in poverty, not to mention all those who hover above said poverty line while working multiple low-wage jobs.

In my building, with the Philadelphia skyline beyond the trees nearby, you have Indian Americans, African Americans, Latinxs, and some East Asian, alongside some whites, who either wait together for the shuttle, wearing their wrinkled dress shirts, or you have many commuting, their name tags glinting under the sun. Most of the apartments here are still relatively cheaper than what you find in the city or in the surrounding areas, and yet, they’re also extremely cramped spaces.

Clearly, people here would benefit from a society where labor is done for public welfare, and where people are promised somewhere nice to live, good food, and healthcare. Right now, when I myself take the elevator, or pass people by, or speak with my neighbors, many of whom are older and African American, I can see the dark rings around peoples’ eyes. They grumble about the pests, the cracks in the hallway letting in rain, the rents increasing. Peoples’ anxieties seep through the walls, sometimes the yelling and slamming of doors jolting me out of bed.

The economic deprivation and loss of economic power can only be resolved through the anchoring of a socialist society and this cannot and will not be achieved through the paradigm we’re trapped in now, which is to keep voting for Democrats and disappearing until the next time a Biden style politician claims to be for “defund” or for “racial progress.”

Yet, to win that society, it requires commitment, passion, and solidarity that is deeper than just voting every few years, if that. Various groups of color must see one another as not just fellow Democratic Party voters but as people worth fighting for, people to trust in times of political disorder or calamity, or during times when repression cracks down over our heads and consciousness.

In political science, there has been a growing body of work having to do with how people of color view one another, politically and socially, which matters to this idea of bridging solidarity, of having people see one another as comrades. Overall, the research has been mixed in its conclusions. According to national survey work conducted by Natalie Masuoka and Jane Junn, various groups of color have internalized racist ideas about each other, ideas that can be exploited by anti-solidaristic political actors. Among some Asian Americans, for instance, the stereotypical beliefs about African Americans, beliefs rooted in white supremacist thinking, are also accepted. Conversely, when it comes to Asians, they are also perceived by African Americans and some Latinxs in an extremely reductive manner, very much seen as “model minorities,” somehow transcending the other problems that other groups face, including economic.

Betina Cutaia Wilkinson, another political scientist who focuses on the relations between African Americans and Latinxs, warned that economic crises can cause groups to battle one another for what they feel are limited resources. They state, “blacks and Latinos who reside in weak economic and political environments are often less prone to feel close to another minority group and are more likely to regard the other minority group as competitors.”

In my own research and organizing, I’ve come across people from various groups of color, including those who are workers, who express some sense of solidarity with others, albeit limited. Some express skepticism. Others feel obliged to say they believe in solidarity but when the topic is explored further, the concept feels vague. For the most part, I do feel most people of color who are workers are interested in improving their working and living conditions, and to do so with others who may not look like them, etc. but this feeling can be fleeting, and will never be strong enough on its own to push a majority to do that work themselves, of bridging divides, of going to a community with different groups of color and conversing.

Overall, there are other competing factors too, even when we focus on working class people of color, however exploited or burdened they may feel. Religion, region, gender (among Asian and Latino men, support for “poc” is lower compared to their female counterparts), and social position (how working people are arranged on the socioeconomic ladder, such as some being “white collar”) matter significantly. In certain parts of the country, like the south, voters of color might feel more eager to throw their support behind Democrats, and restrict themselves in that way politically. In terms of religion, you can find segments of Asians and Latinxs, evangelical for example, who might vote Democrat sometimes, but overall, express a very conservative point of view on numerous topics and issues that affect other working people of color. Age is another important factor as we’ve seen older voters of color believing in the Democratic Party more wholeheartedly, while younger people, at least for millennials, skew increasingly left.

But overall, the cohesion and coherence that’s necessary is still missing and will remain an abstract idea for years to come. How can it not be, considering the lack of robust left-wing alternatives and the continued strength of Democrat establishment politics, as well as the fear (justifiably so) and panic over a resurgent right wing dragging into the public square ghosts of our past, from eugenics to paramilitary groups.

As of right now, the political landscape is ripe for those with explicit class and political interests among our communities to also take advantage and lead us down a cul-de-sac when it comes to political mobilization and action.

Achieving Clarity Against The Tide of Uncertainty

A time period similar to our own is the post-war era following the end of WWII, as a new middle class among some sections of people of color was growing, while most were still trapped in low-wage work and marginalized positions in society generally. In cities like New York, African Americans and Puerto Ricans, two of the major oppressed groups, were very much politically and economically marginalized. The New Deal had done some work in raising up the standard of living and later on, so would Great Society programs, but overall, more had to be done in terms of greatly improving the material conditions of most African Americans and Puerto Ricans, who had now been migrating at greater numbers to major U.S. cities, mainly across the northeast.

Historian Sonia Song-Ha Lee explores this time period in Building A Latino Civil Rights Movement, which examines the political coalitions that were finally forged between both communities in the city.

Initially, despite economic disarray and precarity, many in each group were skeptical of the other. Many African Americans suggested that Puerto Ricans were more privileged and could not be trusted. The irony, of course, is the fact that since Puerto Ricans were relatively newer to the city, the group overall had a far more difficult time accessing stable work, and many more found themselves in poverty. However, many Puerto Ricans expressed their desire, a desire reinforced in them by so-called “community leaders,” to “assimilate” and view their pathway toward greater acceptance as following the experience of European immigrants such as Italians. Basically, the game plan was to bide their time and “prove themselves” to white New Yorkers.

“What Diaz [a Puerto Rican leader] found was a fear among Puerto Ricans that they might become, like African Americans, a people considered to be ‘naturally’ poor and dependent on aid,” Lee writes.

Once again, economic precarity did not naturally lead to solidarity between these groups. Some were seeing more clearly their shared interests, but these people realized too that organizations and institutions had to be developed for most people to finally achieve a similar level of political clarity. Such individuals, as Lee explains, learned the importance and the type of solidarity necessary by cutting their teeth on labor, tenants’ rights issues, and finally, with some having attended major events like the March on Washington, and having ties with figures like Bayard Rustin.

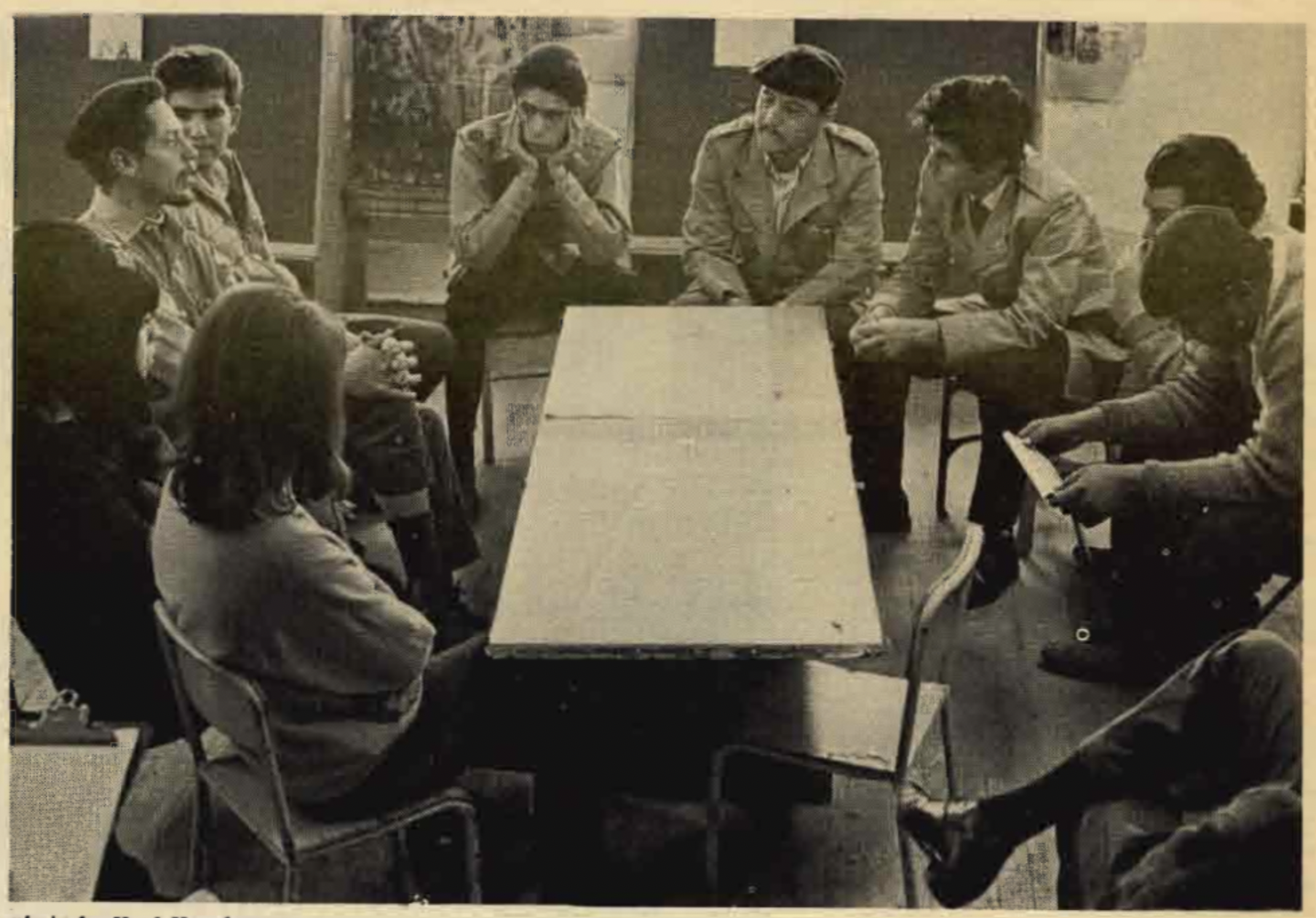

Left-wing Puerto Rican nationalists, like the Young Lords, took direct inspiration from the Black Panther Party, who were also very much driven by an analysis of how various groups of color (even poor whites) are tied politically in terms of their fates, and of course, their need for socialism instead of New Deal and Great Society liberalism. The YL branch in NYC incorporated African Americans into their leadership and organizing, and sought to work with other groups to bring people together from both communities, to have them strategize together, and develop clarity with one another.

“Far from ‘balkanizing’ blacks and Puerto Ricans into isolated, alienated fringe groups, nationalist movements brought them closer together,” Lee states. Over time, this approach did compel enough African Americans and Puerto Ricans to ally together on various campaigns, such as the campaign to diversify education and to have their local schools become more responsive to community needs.

The coalition would break down by the early 1970s for a multitude of reasons. One being the YL moving to Puerto Rico, leaving behind a political void for other types of anti-Marxist nationalist groups or “moderate” elements to fill. There were Puerto Ricans who advocated for shifting away from their alliances with African Americans and toward becoming part of a new Hispanic constituency instead. There were black nationalist groups that once again perpetuated the idea that Puerto Ricans couldn’t be trusted. Finally, a rising middle class of black and brown people meant a new constituency open to more conservative/”moderate” Democratic Party politics as well, such as the mayoralty of Ed Koch, a “law and order” sycophant who pitted group against group, class against class for a right-wing populist vision.

Socialists must lead. There is a growing number of people of color who have shown an interest in broader solidarity efforts. However, this feeling must be further developed into a pro-socialist ethos and anti-colonial struggle. Chaos, crises, precarity will not do the job for us. People will either be compelled to view oppositional politics as voting against the GOP, or for some, leaning on conservative Democrats, or, for some to advocate for such things as petty bourgeoisie forms of so-called economic “autonomy,” as in buying from black-owned, Asian-owned, or Hispanic-owned businesses. More important, or disturbingly so, questions surrounding U.S. imperialism, which affects us as well, will continue to be ignored for the most part, even among sections of people of color who consider themselves progressive-minded.

Currently, socialist groups like the DSA, according to some numbers from the last convention, remain extremely white (85%), with black membership hovering at an embarrassing level (4%). Socialist groups like the DSA clearly lack the presence in communities of color, including lower income. This will lead to other forces swooping in, cultivating relationships for groups to vote against their long term interests, and most of all, to not develop deep political relationships (or even social ones) between segments of Asians, Latinx and African Americans.

Perhaps DSA will not be the vehicle for our communities to win critical demands. Perhaps DSA will be someday replaced with another organization more serious about influencing and organizing black and brown people for a socialist agenda. Regardless, whatever group claims to be the next DSA, or to have the same level of membership (as opposed to what some socialist groups are, which are glorified reading groups still), that organization will need to find ways to intervene, to bring people closer, to educate and develop ties and leaders as did the YL and BPP and others had tried to do in the past, before their own political missteps.