The history of anticommunism in the United States in the post-war era is well documented. Recent scholarship and the availability of newer data from primary sources in the past five years, however, has made it possible to examine the extent to which anticommunism during the interwar years influenced and set the stage for the postwar Red Scare. These developments in the historiography owe much to the work of Ellen Schrecker, whose examination of anticommunism in film, media, and academia helped dislodge the history of American Communism from a history of subversives acting for foreign interests. We now know that this history of radical political and labor activism had extensive domestic roots. Newer scholarship specifically focusing on anticommunism, such as Jennifer Luff's and Donna Haverty-Stacke's works, help shed light on the domestic roots of resistance to communist organizing extending as far back as the early 1920s. This new research seeks to explore the domestic nature of anticommunism and its roots in an era prior to the Cold War era, where Communism as a foreign rival dominated US politics. [1]

According to Jennifer Luff, what we think of as "anticommunism" was a mix of decades-old resistance stemming from antiradical labor activists within the American Federation of Labor between 1921 and 1939 and anti-New Deal Republicans from 1936-1952 that took on the form of a social and political monolith. [2] The FBI's predecessor, the Bureau of Investigation (BI), had, as early as 1921, conducted regular checks on known Workers' Party associates as well as non-Party communists. While many civil libertarians protested the procedure of the BI, the Department of Justice viewed it as "the best way to avoid the snail's pace of the courts" and allowed the investigations to continue throughout the late 1920s and 1930s.[3] Anticommunism has roots in local communities across America, with many of its most effective organizers merely acting as informers and reporters for corporate or government bodies. One way the BI succeeded in localized operations was by relying on private companies that already had the means of infiltrating unions and shop committees. Such was the story of William Gernaey from Detroit. Gernaey's experience helps unveil the complex nature of both anticommunist industrial espionage as well as communist entryism tactics during the peak of the Depression and the early stages of the Popular Front. Both industrial informants and communist infiltrators understood "the skill of semi-illegal methods of work" to avoid being discovered as well as building relationships with fellow workers on the basis of trust and cooperation. In turn, they acted as class collaborationists to help limit the success of communist activism in industrial parts of the nation.

Born in February of 1903, Gernaey grew up the son of a tool and die maker near the east side of Detroit. After graduating from Eastern High School in 1919, Gernaey worked a series of intermittent jobs until deciding to attend Detroit Business University, which eventually landed him a position at the Detroit Independent Oil Company. There, his manager exposed him to Taylorism and efficiency management, as well as the growing effort to extend managerial oversight over the workforce in the midst of a growing national labor consciousness. Gernaey was a typical conservative-minded working class American and believed that the growing labor movement represented a threat to the life his parents worked hard for. He was proud to learn about efficiency management and believed he was helping to make American workplaces both safer and more efficient, thus leading to lower prices and more available products for the average American. Through this process, Gernaey became adept at pointing out ineffectiveness and discrepancies in worker output and managerial authority. He was also popular among the workers; he gave workers the benefit of the doubt in most scenarios and called out the inefficiency of management when he saw it necessary. After the company changed owners in July of 1925, Gernaey received an "anonymous" phone call asking if he would be interested in efficiency work for a private company.[4]

Created in the early years of the 20th century, the Corporation Auxiliary Company (CAC), also sometimes called the Corporation Auxiliary Service, functioned as an administration of industrial espionage that hired organizers and efficiency experts to sabotage industrial organizing efforts and hubs of suspected radicalism dating back to the early 1910s. The CAC particularly built hubs in cities like Chicago and Detroit, focusing on the parts and supply companies for the auto industry. Unlike other espionage agencies that hired gunman and violent strikebreakers, the CAC focused "exclusively on spying." By the mid-1930s, from '33 to '36, the Chrysler Corporation provided the bulk of CAC's funding, amounting to $275,000 over the course of three years. The CAC's promises to its clients were to penetrate union leadership positions and lower-ranking union member meetings to stimulate "racial antagonism in the union ranks" as a means to "undermine strike solidarity" and turn over the names of leading organizers to the company.[5]Most company spies, including Gernaey, faced exposure by sit-down strikers in 1937 and were identified to their union as company stool pigeons, effectively ending the highly influential role of the CAC on business practices in industrial cities. Those hired by the CAC and left without a job typically turned to management services for companies such as Ford, or to the federal government and subsequently employed by the FBI.[6]

One such effort by the CAC in the mid-to-late 1920s involved the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) and an investigation as to the extent to which communists influenced local labor union halls in cities such as Detroit and Chicago. This was during an era of the evolution of early anticommunist strategy that attempted to rationally combat the movement as opposed to placating it publicly as a pariah. Individuals like Gernaey were "not paid to help build the Communist Party, but rather to help, in whatever way possible, to break it down." To facilitate this espionage, the CAC's spies infiltrated local union efforts under the auspice of a genuine industrial worker; a tactic nearly identical to the 1920s unionist method of "entryism" promoted by leftist, syndicalist, and communist groups. Informants had to "gain the confidence of the people within" and most importantly "gain leadership" as a means to combating the persistent search for "stool pigeons."[7] When convincing employers to accept contracts, the CAC assured them that their informants and subversives would "get acquainted" with the workforce and "engineer things so as to keep organization out." Should this first effort fail, the informant would then "become the leading spirit and pick out just the right men" to lead the organization so as to assure its inevitable failure.[8]

Gernaey found his way to the CAC headquarters located in the Hoffman Building at Woodward and Sibley. Hired to perform "efficiency work" on behalf of the local business community, Gernaey was told that his employment would be contractual with individual clients. The company admitted to gathering data on his work with Independent Oil via their own internal sources and expressed promise in his ability to navigate between the sentiments of management and workers. For his first assignment, the CAC sent him to Shell Oil, followed by the Wayco Oil Company. While given a position and a manager to report to, Gernaey's managers were never made aware of his role as an efficiency expert. Working the factory under the auspice of an average worker, Gernaey "wrote daily reports of activities, sentiment of the employees, supervisors, etc." Gernaey also tried to imbue his fellow workers with etiquette, routinely instructing them on "how to conduct the work, give service, [and] courtesy." In under a year, Gernaey performed exceptionally for various oil companies in the city through CAC. He even prevented the loss of around $50,000 in oil after discovering a secret plan to steal oil reserves. To perfect his skills as a subversive efficiency expert, the CAC sent him semi-weekly lessons on "Time Study and Efficiency Detail." After working for the company for two years, he was given an assignment that would change his life forever.

In early 1927, the CAC tasked Gernaey with infiltrating the Chrysler plant in Highland Park just Southwest of Detroit. After obtaining an assignment on the line, Gernaey began his observatory work and his reporting of inefficiency; such as reporting foremen who pushed workers to the point that they quit, criticizing workers who slowed down the line and encouraging fellow workers to avoid loss of material. Like many of his previous jobs, Gernaey found it easy to get along with his fellow workers and showed little favoritism over efficiency issues. He also avoided reporting certain incidents such as theft and petty grievances because to do so would threaten his nature as a subversive for the company. Gernaey worked in the plant for two years, until being laid off in the spring of 1929 due to the early stages of the Depression. His managers could not make an exception for the very simple fact that they were unaware of his role in the company. This did not deter his employers, however, who desired to see him continue his work in another way: They asked him to infiltrate the local Detroit communist movement.

In 1929, the American Communist movement was emerging into its "Third Period" of organization where its goal was to contrast the goals of socialism against so-called "progressive" and "social-fascist" organizations such as the Socialist Party and segments of radicals who left the CPUSA on the grounds of their support for Russian Revolutionary Leon Trotsky. In Detroit, the CPUSA focused its efforts on organizing the factory and auto workers as well as combating discrimination of non-whites. The CPUSA's national tactic for organizing was the creation of radically-led communist unions under the umbrella of its Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), headed by CPUSA Presidential nominee William Foster. In many cities, however, such as Detroit and Chicago, the local scene of labor dictated the what path the communists would follow as opposed to the national leadership of the Party's preferences. In the case of Detroit auto workers, entryism, or "boring from within," was the preferred tactic.

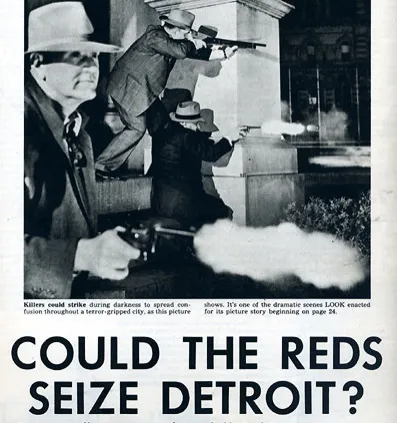

As far as domestic anticommunism at the time, recent research suggests a pattern between the development of "armchair anticommunism" who worried about the "social anarchy" of revolution and labor anticommunists who sought to curb the political influence of radicals in both the unions and in broader society. On the whole, however, American Communism "held little appeal for Americans" and thus the efforts to resist it as a movement were more of an attempt to expose the presence of communists as opposed to counter their methodology or philosophy.[9] Most average Detroit citizens believed that "communists were all foreigners or Russians with beards and bombs" and had caricatures in newspapers to sustain this image. The business community of Detroit was likely aware to some degree of the presence of communist organizers, but certainly not to the extent to which they had influence among the local workforce by 1929. To find the extent of communist presence and expose it, business leaders turned to companies like the CAC and men like Gernaey because they were effective but more importantly expendable units in the effort to identify communist organizers.

Gernaey was instructed by his adviser to attempt to join the CPUSA by "hanging around communist halls," which he learned quickly was a mistake. His first attempt at mingling with workers in labor-oriented bars "showed [him] that every communist is suspicious of a stranger." To get involved, Gernaey needed a direct in and he needed more than just placement to obtain it. He needed to build a character, and role play, with a background and an identity that gave purpose and meaning to an affinity for communism. Once he was ready, he attended a "youth mass meeting" at Grandy Hall on Theodore Street where he met Max Shapiro and Joe Siroka and two other organizers, who were the only men attending the "mass meeting." Gernaey told the local CPUSA and Youth Communist League (YCL) organizers that he was "a beraggled young fellow without a home, job or means to get a meal." As the only attendee of the meeting, the four men sympathized with Gernaey, fed him, and gave him instructions on where to find the next meeting.

The next night, Gernaey went to 2984 Yemens Street, where an underground restaurant was hosting a meeting for the local CPUSA district. In the restaurant, CP organizers and YCL leaders were spread out at different tables, talking amongst themselves about their hopes and plans for the coming months. Once the meeting started, Gernaey learned a few things about his local communist scene, namely that "plans [were] rarely carried out" and the district local was more talkative than it was effective at agreeing on what to do. When asked openly by the district leaders why he decided to join the CPUSA, Gernaey responded by saying "a new broom always sweeps best." Gernaey's commitment to his role resulted in precisely what the CPUSA wanted to hear: acceptance of the new Third Period program, rejection of the old ways. As far as the district leader Joe York was concerned, Gernaey "was in."

Despite "losing" his job with Chrysler, Gernaey ate for free while working with the local CPUSA, and was also offered places to stay rent-free. At the first meeting and in subsequent months Gernaey made friends with Mary Hemoff, a Central Committee member for the Michigan CPUSA and member of the National Secretariat of the YCL. In less than a month, the CPUSA sent Michigan leader Joe York to the Soviet Union to study labor theory, and Gernaey was handed the job of organizing Hamtramck and Northern Detroit and keeping watch on the local YCL. Within a few weeks, Gernaey noticed common trends within the Detroit CP, such as high turnover rate for membership but low turnover for leadership. Additionally, because the CPUSA remained isolated and removed from the broad masses of Detroit amidst its shifting base membership, the leadership formed "a bureaucratic clique." Within his local YCL meetings, he noted a tendency for the members to prefer study periods over discussions about activism. This sort of general malaise among local communists is not unknown; numerous examples of the CPUSA's limited organizational capacity exist in the historiography, such as future CPUSA leader John Gates' preference for attending reading seminars at college instead of organizing local workers.[10] Due to his tenacity as a newer member, Gernaey was offered the chance to attend the Lenin School in the Soviet Union, but turned it down. While accepting his role within the CPUSA as necessary for his goal as an informant, he felt that by accepting formal education in a school of Marxism he would undo his self-respect and become too caught up in the bureaucracy of the movement.[11]

In February of 1933, Gernaey and the local Detroit CPUSA found their first major moment when the employees of the Briggs Manufacturing facility went on strike over a wage cut. Nationally, the CPUSA reported the strike as the result of Briggs workers suffering as "the most exploited in the entire auto industry" throughout the early years of the Depression.[12] The company refused to negotiate with the strike committee on the grounds that they were communists. Workers, in turn, denied the charge and emphasized their use of American flags and the exclusion of communists from committee leadership positions.[13] Gernaey, however, reported that the Party not only had operatives within the plant including himself, they also were voted to the shop committee leadership. As the strike committee's lead organizer, Gernaey led "in all discussions on maneuvers and policy" and litigated employees on how to carry out the committee's demands.[14] A local radical publication, the Detroit Leader, responded in turn by telling Briggs factory workers to recognize "the class struggle" and accept that "the interest of the workers and the employers are never identical."[15] Again in 1934, because of his work during the Briggs strike, nation CPUSA leader William Weinstone gave him a chance to attend the Lenin School, and again, Gernaey turned the offer down.

From then on, Gernaey set his aims at breaking up the YCL and the overall effectiveness of the CPUSA at the community level. To accomplish this, he took steps to disrupt the attempt of the Party to engage with the public. His first attempt occurred on May 30th, 1935, when the district CPUSA organized an anti-war demonstration in Grand Circus Park. Gernaey told his YCL district to instead act as "nuisances" and ordered his comrades to remain isolated, avoiding the baseball crowds and masses marching for Memorial Day. Instead of marching on Grand River, where the CPUSA desired the members to be active, Gernaey held his YCL parade several blocks from the main boulevard, and began at 1pm "when the crowds [were] at their weakest." Gernaey also redirected pro-labor parades away from downtown regularly and avoided organizing near the major Dodge plants.[14] Despite numerous successful attempts to split and slow down the local effectiveness of the YCL, Gernaey retained his leadership position until by the end of 1935 he was formally brought into the CPUSA, given the title of district organizer for the Labor Sports Union (LSU), and a weekly salary of $5. Gernaey continued to command the local YCL as well, but his covert activities did very little to tip off local and national CPUSA leaders.[16]

At LSU, Gernaey met and worked with George Kristalsky and Jack Mahoney in Hamtramck to staff a local unemployment council. Unemployment councils were the bread and butter of the early-to-mid 1930s American Communist movement. Organized as a local response to the conditions of the depression, their history was rooted in an effort to "organize the unemployed" and the semi-joint effort of the CPUSA, the Socialist Party of America (SPA), and the Trotskyist Communist League of America (CLA). Between 1930 and 1932, the councils found common ground to build what they called a united front against unemployment. While never as successful in terms of policy as they were in numbers and popularity, the councils did serve as the basis for maintaining a cooperative alliance between Leftist groups in the early 1930s despite the Third Period ideology of resisting cooperative work. In other cases, they served to further divide Leftists as was the case in Chicago, 1932.[17] By 1935, the councils served as a membership recruitment system in industrial areas like Detroit. This process began after the Socialists refused to support the CPUSA's banners and symbolism in 1932, and as the depression worsened to increase evictions across the nation. Gernaey watched as his YCL local became infused with numerous new "young ruffians" who turned to militant radicalism and wanted to physically resist the efforts of landlords. To maintain his leadership, Gernaey did little to stop the younger members from putting the furniture back into homes after evictions and climbing telephone and electric poles to reconnect houses to the grid. By 1935, however, the CPUSA was beginning to change and so was their dependent unemployment councils.

Many organizations the CPUSA tacitly or overtly supported prior to 1935, such as the Ukranian Women's Club and the Russian Workers' Club, were liquidated to streamline meetings together and tighten up the local Detroit membership. The Detroit Unemployment Council was renamed the Workers Alliance Local and communists were instructed to direct their attention toward the organization of Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers. To secure their control over local unions, such as Teamsters Local 830, communists on the shop committee placed fellow comrades into the best positions and delegated the most difficult work to workers who refused to join. While the union attracted numerous WPA employees who were desired for their skilled labor, communist shop leaders ensured that initial meetings were mixed with an effort to encourage involvement in local CPUSA politics. Through his work with the WPA employees, Genaey found that communist organizers were exceptionally skilled at performing their "semi-illegal" activities while simultaneously embodying the idea of an "elite" Communist Party member. Likewise, the most active and visible communists within a union local or a community had "very little time for amusements." As representatives of their national Party, they went from meeting to meeting, event to event, dressed as professionals and financed by the Party to appear as the most successful of workers.[18]

Gernaey's work with the CPUSA continued unabated until spring of 1937 when two men entered the CPUSA office in Detroit and handed him a call letter to testify to the La Follette Committee in Washington. At the time, the La Follette committee was exposing the work of numerous CAC informants at various levels throughout Detroit. After agreeing to testify, Gernaey was told to leave Detroit. It was the belief of his non-communist associates that the labor movement would only continue to organize and retain communists in leadership positions, effectively limiting Gernaey's ability to remain active. He returned all of his union-related property, such as his typewriter, books, and stationary, and severed his ties with the local CPUSA. Quickly, the union issued a request to hold a public trial of Gernaey as a possible spy, which he avoided. Only a few days after the trial, Gernaey was told that the CAC was going out of business as a result of the continued exposure of its informants. When Gernaey pressured his boss to explain how the union became aware of his testimonies, he was told that the union or the local communists likely went through his mail or had figured out a discrepancy in post office box numbers between union members and Party members. The local CPUSA responded in full force, placing Gernaey's photograph in the pages of the Daily Worker and labeling him and all company informants as "rats." Also in less than a year, Gernaey's wife left him for a family friend and filed for divorce.[19]

The early work of William Gernaey is a watershed moment in the research of early American Communism and the roots of domestic anticommunism. Gernaey went on to testify before the Dies Committee, work as a subversive within the Ford Motor Company, and eventually hired by the FBI. What is compelling about Gernaey's story is the way it highlights anticommunism as a localized effort, and more importantly one that extends from specific business communities as opposed to industry or politics at the national level. Such a development took the onset of the Cold War and the rampant tensions of postwar Europe. It also helps further understand domestic anticommunism as a phenomenon taken up by both companies and individuals for personal reasons. For the CAC, anticommunism was business and throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, business was exceptionally good. Gernaey's testimony helps to show that for individual informants, much of their work was seen as a natural extension of their skills and passion for the ideals of capitalism. It is important, moving forward, to understand anticommunism as both endemic of the postwar Cold War, but also rooted in domestic, localized business interests in terms of controlling and swaying workers' sense of ideological commitment.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Jennifer Luff, Commonsense Anticommunism, First (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Ellen Schrecker, “McCarthyism and the Decline of American Communism,” in New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1993); Donna T. Haverty-Stacke, Trotskyists on Trial, First (New York: New York University Press, 2015). ↩

- Luff, Commonsense Anticommunism, i–iii. ↩

- Ted Morgan, Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America, First (New York: Random House, 2003), 60–61. ↩

- William Gernaey, “Autobiography of William P. Gernaey,” October 10, 1940, Box 1, Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. ↩

- Stephen H. Norwood, Strikebreaking & Intimidation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 204. ↩

- Norwood, 173. ↩

- Gernaey, “Autobiography of William P. Gernaey,” 7. ↩

- Harry Wellington Laidler, Boycotts and the Labor Struggle Economic and Legal Aspects (New York: John Lane Company, 1913), 291. ↩

- Luff, Commonsense Anticommunism, 134–35. ↩

- John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1958). ↩

- Gernaey, “Autobiography of William P. Gernaey,” 12. ↩

- “Some Lessons of the Strike Struggles in Detroit,” The Communist 12, no. 3 (March 1933): 197. ↩

- Samuel Romer, “The Detroit Sit-In Strike,” The Nation, April 23, 2009, https://www.thenation.com/article/detroit-sit-strike/ ↩

- Gernaey, “Autobiography of William P. Gernaey,” 9. ↩

- “To The Briggs Strikers” (The Detroit Leader, April 1, 1933), Joe Brown Collection, Box 19, Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. ↩

- Gernaey, 10. ↩

- “Oppositionist Speaks at Party United Front Meet,” The Militant 5, no. 19 (May 7, 1932): 4. ↩

- Gernaey, “Autobiography of William P. Gernaey,” 13. ↩

- Gernaey, 32. ↩