Contrary to persistent accusations that Marx—and Marxism generally—reduced the world to economic systems, an understanding of ideology and its vital function in maintaining capitalism is key to a Marxist orientation to the struggle of working and oppressed people. Marx understood that ideology is absolutely essential to presenting capitalism as natural, ahistorical, or benevolent. Central to this ideological stability is alienation, which propagates false consciousness in large segments of the masses and, in so doing, enlists them into the process of social reproduction. False consciousness obscures relations of power, whereby the oppressed identify with their oppressors. In addition to promoting the shared identity of the dominant and subordinate in favor of the former, alienation and false consciousness serve to cover up the shared interests of subordinate or subaltern groups. Sectarianism among the subaltern stems from their alienation which is, in turn, intensified by sectarian divisions. Induced by alienation and false consciousness, the oppressed come to identify with their oppressors and in opposition to other subordinate groups, thereby encouraging their participation in processes of reproducing the conditions of oppression. A similar dynamic characterized the personal experiences of Antonio Gramsci, whose works on the North/South division in Italy remain some of the most insightful analyses of the division of urban and rural working class.

Internalization of ruling class identity and interests

Alienation obscures the conditions of oppression and the relation of segments of the subaltern to structures of power—most often along collective narratives of race or nationality. This social dynamic can be seen throughout the history of capitalism and colonialism at both national and international levels. Through what W.E.B. Du Bois refers to as the wages of whiteness, working-class whites in the U.S. identify with wealthy whites in order to elevate their social status.[1] This largely illusory sense of power has led many impoverished whites to consent to a system which appears to make them benefactors but in reality, exploits them. The fact that racist sentiments are often most loudly pronounced by those with little or no social, political, or economic power should not be overlooked. As Sartre states,

the rich for the most part exploit this passion for their own uses rather than abandon themselves to it … It is propagated mainly among the middle classes because they possess neither land nor castle…By treating the Jew as an inferior and pernicious being, I affirm at the same time that I belong to the elite.[2]

Clinging to such prejudices gives the powerless a false sense of shared interest with the powerful. They, therefore, are all the more encouraged to reinforce the structures that afford them what is often only the illusion of benefit.

Similarly, Marx saw the division of and antagonism between English and Irish workers as playing a fundamental role in the former’s identification with the English ruling class and the maintenance of capitalist relations of production. For his perennial relevance on the matter Marx deserves to be quoted at length:

Every industrial and commercial center in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker, he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the Negroes in the former slave states of the U.S.A.. ... This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organization. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.[3]

The above excerpt speaks to the need of the ruling class to create and intensify ethno-racial antagonism amongst the lower classes. English aristocrats and other ruling elites compromise the power of the subaltern masses by convincing the English or white workers that the Irish or non-white workers are the source of their problems rather than the ruling elite they are led to identify with. This antagonism is perpetuated by a capitalist superstructure which naturalizes the system of exploitation and diverts scorn back on segments of the working class.

On an international level, nationality also serves to disguise the power dynamics within nations and create a consensus for imperialist expansion. This can pacify and, when it is most successful, redirect the aggression of those afforded the least of a nation’s prosperity to an externalized other. With such cases, the collective sense of national identity can become all the more ideologically potent and thus essential to the cohesion and reproduction of both national and international systems of exploitation. This phenomenon occurred globally with the outbreak of World War I. The first decades of the 20th century were characterized by growing unrest and revolt to the increasingly inhumane system of international industrial capitalism. With the overthrow of the Russian czar, eventual Bolshevik Revolution, the establishment of worker’s soviets, and a global sense of unrest international socialist revolution seemed an all too possible threat to the capitalist order. The conception of shared national identities served to redirect tension away from the politicians and business tycoons and thus isolate the Soviet Revolution. Socialist organizing was dealt a severe blow in countries like the U.S. and Germany where a spirit of jingoism pervaded. The question of national identity and world war divided the ranks of many major socialist parties thereby interfering with international worker solidarity and recruiting some for the cause of kings, kaisers, and capitalists. Under the guise of patriotism and national interest, it also provided popular support for the coercion of those in opposition to the war and the imperialist system from which it grew.

These ideological distortions can and do go further than the minds of people that reside within an imperialist nation and those required to colonize or enforce imperialist order. The colonized often also show a similar tendency to identify with those that oppress and exploit them. Franz Fanon explores this sociopsychological trait in his Black Skin, White Masks. According to Fanon, “the Antillean does not see himself as Negro … Subjectively and intellectually the Antillean behaves like a white man. But in fact, he is a black man.”[4] The colonized mind is inundated with hierarchical social categories with which to interpret and relate to society. They are directed to identify with oppressors because they are taught to think like and by colonizers. In being reduced to a passive receptacle for the knowledge of the oppressors. "the Antillean has the same collective unconsciousness as the European…Through his collective unconscious the Antillean has all the archetypes of the European.”[5] As a result of internalizing the archetypes or principles of division of the colonizer, the colonial subject takes for granted the relations of power. The depositing of such social visions facilitates the formation of false consciousness in which the colonized see themselves as potentially sharing a common identity, position, or interest with the colonizer.

Misrecognition of subaltern struggles

In addition to obscuring the relations of the oppressed to the oppressor, alienation obscures the relationship of oppressed people to one another. This creates fragmented liberation movements that work at odds with one another in which adherents do not recognize the totality of exploitation that connects various forms of oppression. In taking the dominant categories of this division for granted, the subaltern comes to “utilize the same instrument of alienation in what they consider an effort to liberate … But one does not liberate men by alienating them.”[6] Sectarianism, therefore, serves to reproduce rather than transform or topple structures of inequality and exploitation.

From the colonial era to the present day, much of the struggles of subordinate groups to attain rights have been fraught with sectarian and reactionary tendencies. This was particularly true of many suffragist organizations. In the first half of the 19th century, Thomas Dorr led a group of suffragists in Rhode Island. Initially, in support of extending the vote to the Black community, the Dorrites came to reject the cause of racial equality. Codified in their Convention of 1841, these suffragists saw the political enfranchisement of Black people as a threat to their own suffrage and politics more generally. Shortly after, the Dorrites attempted an abortive uprising against the small rural elite that controlled Rhode Island politics. This rebellion was put down, in part by the Black community that had supported the group prior to their rejection of Black suffrage.[7]

A similar sectarian tendency divided the cause of women’s suffrage in a way that reinforced class and racial inequality.[8] Codified in the Seneca Falls Declaration, a dominant sect of suffragists rejected the struggles of both working-class white women and Black women. Rather than fighting for the rights of all women as an oppressed group, such movements were about asserting the dominance of wealthy white women. Likewise, many men in the abolitionist movement rejected the struggle of women and claimed such concerns would only interfere with the struggle for racial equality. Both tendencies promoted the reproduction of gender inequality. Whether dividing the subaltern along conceptions of ethnicity, gender, or another taken-for-granted principle of division “sectarianism in any quarter is an obstacle to emancipation.”[9] People like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Claudia Jones were keenly aware that solidarity would be essential to adequately combat the larger system of exploitation and oppression that is the international capitalist order. Regardless of intent, turning the struggle for human liberation into unrelated or conflicting issues reinforces the conditions of oppression. Contemporary examples of this include bourgeois or liberal feminism which equates the representation of women within the current structures of power with equality. In the same vein as the wealthy white suffragist sect mentioned above, this corporate feminism rejects the class struggle and cynically pays lip service to demands of racial equality.

Unlike the above critique—to which alienation and false consciousness are central—pervasive and insidious liberal ideology encourages people to take social relations for granted. What is, in reality, a collective struggle grounded in material conditions of the oppressed is perverted into individual endeavors to simply perceive inequality—an idealist rather than materialist conception.[10] As such, privilege is seen as central to maintaining social inequality and oppressive relations. Under this paradigm, it is the conscious desire to preserve privilege that reproduces inequality. However, there are fundamental problems with this line of reasoning. First, it is a tautological argument. Privilege is inequality experienced from the position of the dominant group. Therefore, such statements ultimately say that the desire to preserve inequality is what preserves (or reproduces) inequality. A second, more substantial critique of this individualistic understanding of power is that it reduces all social processes to the conscious decisions of agents. It, therefore, ignores the role of dominant ruling class ideology, structures of power, and their influence on agent dispositions and actions. The liberal narrative that puts privilege front and center do not consider how ideology informs people’s behavior and how it distorts conditions and relations oppression. It therefore also overlooks "the tendency of structures to reproduce themselves by producing agents endowed with the system of predispositions which is capable of engendering practices adapted to the structures and thereby contributing to the reproduction of the structures.”[11]

This line of reasoning is, in fact, a product of bourgeois ideology which corresponds to established relations of exploitation and oppression. In explaining inequality as a matter of well-informed agents, such critiques of power suggest oppression is a natural outcome of self-interest. This reduces social processes to composites of individual decisions and obscures the role division of the subaltern plays in maintaining hegemony.

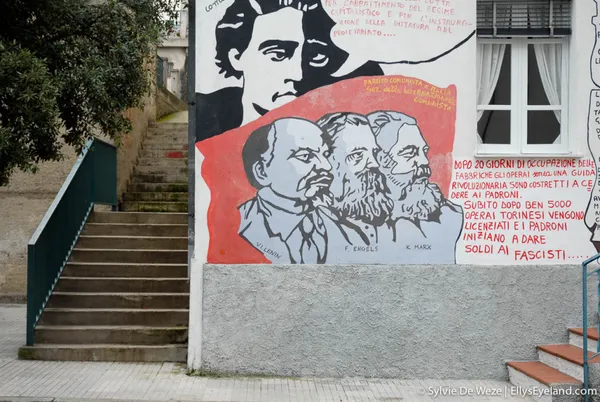

Antonio Gramsci and the North/South division in Italy

The distinction between reacting against oppression while adhering to the naturalized premises on which these structural relations are founded and outright rejection of the ruling class’ divisions of the oppressed is absolutely essential. Having experienced this social dynamic personally, Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci offers this vital lesson in both his works and life. Born in the small town of Ales on the remote island of Sardinia on 2 January 1891 Gramsci experienced the internal division within Italy’s subaltern masses and saw, over time, its function in maintaining hegemony. Located in the Mediterranean Sea between mainland Italy and North Africa, Sardinia’s history is characterized by extreme rural poverty and exploitation at the hands of mainland Italians in the North.

Despite his early interest in socialist thought, Gramsci’s initial intellectual character was shaped more by the exploitation of Sardinians at the hands of the Italian mainland and Sardinian nationalism created by mainland exploitation. In the mind of young Gramsci, the social relations of Italy could be summed up as the subjugation of the Mezzogiorno (the South) by the Settentrione (the North). At this time in his life, he was in favor of Sardinian independence rather than liberating all of Italy’s subordinate classes. Later, he would reflect on his incomplete consciousness: “I used to think…that the struggle for Sardinian national independence was a necessity. Continentals go home!—how many times have I myself repeated these words.”[12] As a young Sardinian, Gramsci internalized the city/countryside division which he would later denounce.

Historically, the antagonism between Italy’s rural and urban populations served to divide the country into the rough dichotomy of North and South. This division required a mutual distrust or hatred between the urban and rural masses. In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci reflects on the fact that in urban areas:

there exists, among all groups, an ideological unity against the countryside … there is hatred and scorn for the “peasant,” an implicit common front against the demands of the countryside … Reciprocally, there exists an aversion—which, if “generic,” is not thereby any less tenacious or passionate—of the country for the city, for the whole city and all the groups which make it up.[13]

Prior to his experiences as a student, activist, and journalist in Turin Gramsci certainly did share this aversion for the urban population and the mainland in general which he saw as comprising a single class of oppressors. At this time, he was attached to only one side of the national system of domination and exploitation. Nonetheless, the subjugation and struggle of the Sardinian workers served to initiate Gramsci’s unwavering partisan stance, which he would keep for the rest of his life. In 1904, the island’s salt miners went on strike in to demand an end to the brutal working conditions they had to face in the mines. On September 4 an altercation broke out between the miners and mainland troops in which the troops killed three people and wounded eleven more.[14] Two years following this incident a wave of protest swept over the island and it too was put down by mainland troops.

Events like this fueled hatred for all northerners in the minds of Gramsci and his fellow Sardinians—a hatred that was returned by most northern Italians. Such mutual hostility among subordinated or subaltern classes was a socio-historical construction introduced by the dominant urban and rural classes which served to maintain hegemony via consent of the divided masses. While Gramsci would later overcome such convictions, his early experiences and beliefs—centered largely on Sardinian nationalism—would set him apart from his mainland counterparts due in part to the fact that he had intimate contact with the problems peasants had to face. In fact, many people in the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) accepted that the southern peasants were inferior to varying degrees and therefore did not wish to align the city and countryside. Even Antonio Labriola, who had a significant influence on Gramsci’s own understanding of Marxism, saw rural Italians as a backward and burdensome class. Northern proletarians and even Marxists often looked down on southern peasants in much the same way the white and English working classes looked down on black and Irish workers in places like the US and England.

The oppressed masses of both urban and rural Italy internalized the “common sense” (taken for granted assumptions/views) that was introduced by Italy’s dominant rural and industrial classes so as to maintain their position. This division serves to weaken and disorganize the subordinate masses by obscuring the group’s interests and who it perceives as its enemy. In Sardinia, this often took the form of brigandage—a form of dissent that Gramsci (and other Sardinians) romanticized for a time as a child. It was only after his experiences in the industrial city of Turin that he began to see these acts as futile and misguided due to “common sense” of the North/South dichotomy.

From Sardinia to the Mainland

Gramsci left Sardinia in 1911 to study at the University of Turin before devoting himself entirely to the cause of the Italian working class first as a journalist then as an organizer, politician, and leader/co-founder of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). Fundamental to Gramsci’s development from a Sardinian nationalist to a key proponent for a revolutionary worker/peasant (North/South) alliance was the military repression of Turin auto-workers in 1917 a part of which was the Sassari brigade from Sardinia.[15] This situation illustrated the complexity of mutual aversion and domination. Just as mainland troops repressed Sardinian peasants demanding better working conditions in the salt mines, now Sardinians were contributing to the repression of northern proletariats. He could no longer claim Sardinians were merely victims of the North’s draconian rule as he had once done and as a Sardinian soldier expressed to Gramsci during the two Sardinians’ interaction:

Soldier: We are here to shoot those lords [signori] who are on strike.Gramsci: But it is not the “lords” who are on strike; it is the workers and they are poor.

Soldier: Here everybody is a lord. They all have a coat and tie…[16]

Gramsci thus came face to face with the perception of his childhood during which he was able to see how it did not reflect the actual complexity of Italian class relations. He came face to face with the division of the subaltern against itself. According to the Sardinian historian Giuseppe Fiori, Gramsci "began to see clearly that the real oppressors of the southern peasants …were not the workers and industrialists of the North, but a combination of the industrialists and the indigenous Sardinian or southern ruling class as a whole.”[17] Seeing Sardinian troops in the same position as mainland troops in Sardinia, Gramsci realized that the North/South relationship was much more complex than the popular Manichean dichotomy could account for. Both the peasants of the South and the northern proletariat were subject to harsh repression in order to maintain hegemony throughout Italy. In addition, both subaltern classes may at times be used to repress one another whenever one does not consent to the hegemonic powers—thus making the mutual hatred between them essential for the dominant class. For Gramsci, this hatred or distrust is cultivated by misrepresentation or misrecognition in which the one subaltern group believes another to be dominant or an impediment on their liberation. Historically this has meant peasants viewed proletarians as “lords” while the proletariat viewed peasants as remnants of a feudal past that served as a backward and inferior “ball and chain” holding northern Italians back from true progress.[18] Both subaltern classes wrongly blamed one another for their position in society rather than the ruling elite that introduced and exploited the division of city and countryside.

Prior to such experiences, Gramsci blamed all of the North (including the workers) for the subjugation of the Mezzogiorno. He came to realize that peasants needed the urban working class to claim the land and the urban workers needed the peasants to overthrow capitalism. As such, he rejected the alliance between landowners looking to avoid mainland taxes and the mass of oppressed peasants in which the latter wrongly believed in the benevolence of the former due to a shared identity that did not consider uneven power dynamics. This common relationship perpetuated the social, political, and economic oppression by landowners. The proletariat of the North could not liberate itself in isolation from the rest of the subaltern masses largely because all those groups not aligned with could serve either as replacement labor or potential soldiers to be used by the hegemonic power to reassert itself. The same could also be said of southern Italians/peasants who looked to revolt against their subjugation. Divided, Italy’s subaltern masses were too weak and disorganized—and in some cases, they could even be a threat to one another. It is these acts of coercion of one subaltern class by the other that serves to intensify the antagonism between city and countryside—an antagonism necessary to divide and rule both the proletarians and the peasants. Therefore, a national-popular movement—defined as a moment in which a class can become "hegemonic at a national level by drawing subaltern social groups into an alliance.”[19] This was necessary for the overthrow the alliance between capitalism and the remnants of feudalism (i.e. southern landowners) in Italy. This mutual dependence necessitates breaking down the divisions of the subaltern.

Conclusion

Alienation provides stability to an otherwise volatile system of exploitation by enlisting the oppressed in processes of social reproduction. Jingoism, nativism, white supremacy, regionalism, and the colonized mind that stems from alienation and subsequent false consciousness all function to mislead the subaltern masses to identify with the powerful. Alienation also propagates sectarianism among the oppressed. Such antagonisms, while occurring between people claiming to be liberators, maintain structures of oppression by taking for granted the divisions with which the dominant manage those beneath them. Sectarians maintain the categories and subsequent relations of the oppressor among the oppressed. This hostility encourages the subaltern masses to divide and oppress themselves. The consent of alienated segments of the subaltern masses gives the ruling class the ideological power necessary to coerce other segments. By addressing the false consciousness that bourgeois ideology propagates the underlying material conditions can be transformed. While reproducing relations of exploitation rests on alienation and division, socialist transformation of society must rely on solidarity as the basis for all liberation. This requires working patiently yet diligently with the subaltern masses to promote a revolutionary class consciousness which pits them against the ruling class rather than against one another.

Work Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre 1974, “Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction” in Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change: Papers in the Sociology Of Education. Edited by Richard Brown. London: Tavistock Publications.

Davis, Angela 1981, Women, Race, and Class. New York: Vintage Books.

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1935, Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward the History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Fanon, Frantz 1952, Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Fiori, Giuseppe 1971, Antonio Gramsci: Life of a Revolutionary. New York: Dutton.

Freire, Paulo 1972, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Gramsci, Antonio 1972, Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: International Publishers.

Gramsci, Antonio 1988, An Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935. New York: Shocken Books.

Gramsci, Antonio 1994, Pre-Prison Writings. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Marx, Karl 1870, Letter to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt.

Roediger, David R. 1999 [1991], The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. New York: Verso.

Santucci, Antonio A. 2010, Antonio Gramsci. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Du Bois 1935.Roediger 1999. ↩

- Quoted in Fanon 1952, pp. 67-68 ↩

- Marx 1870. ↩

- Fanon 1952, p. 126. ↩

- Fanon 1952, p. 168. ↩

- Freire 1972, p. 66. ↩

- Roediger 1999, p. 58. ↩

- Davis 1981. ↩

- Freire 1972, p. 22. ↩

- See Marx’s The German Ideology for a distinction between ideologist and materialist conceptions. ↩

- Bourdieu 1974, 56. ↩

- Quoted in Fiori 1971, p. 50. ↩

- Gramsci 1972, p. 91. ↩

- Fiori 1971, pp. 35-6. ↩

- Santucci 2010. ↩

- Gramsci 1994, p. 320. ↩

- Fiori 1971, p. 88 ↩

- Gramsci 1972, p. 71. ↩

- See Glossary in Gramsci 1988, p. 426. ↩