Shame and the mass psychopathologies of the gay man

"It is not enough to say that shame and homosexuality are closely connected. One only exists in the movement of the other"-Guy Hocquenghem[1]

What is the gay man? What is his history, the man who has sex with men? How has culture, economics, and social life been mediated by this new category, this new identity? How has it also come to be that there is now a gay culture, with gay economies, with political geographies?

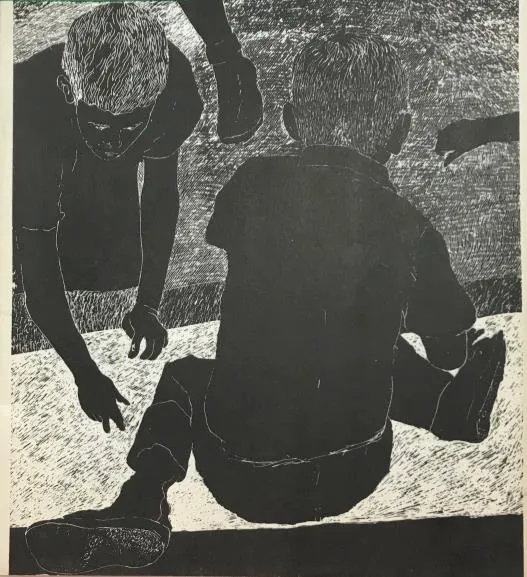

We can answer these questions in a number of ways, but not without first painting a necessary backdrop of a gay lived experience; this subjective element isn't one we can universalize, but it is still our starting point if we are to find unity in an alienated, disparate history. There is a boy, loathed by his father, inadequate to his peers, as well as the bearer of the heaviest, most painful secret a boy can have. For him, his primary source of security, care, development, and social reproduction is a unit he not only is anomalous towards but is perhaps a failure to. At worst, a social and material estrangement will require him to navigate society alone, desperate to make a “family” of his own. For many this is difficult to bear: it is not a secret that gay men are a damaged and wounded lot. Dark closets can rule the lives of the loudest and proudest of them. Through the forces of misery and shame, they find themselves trudging much more easily to a hell which does not scare them than back from it, when it comes time to simply exist.

Thus the little boy with the big secret carries with him a great inadequacy for which he must compensate for. There are no clothes or body with the correct aesthetic, there is no validation that is too little or too inauthentic. There are never enough drugs, never enough sexual partners. There is not enough masculinity, there is not enough flamboyancy. Fulfillment, the achievement of genuine happiness in gay lives, is virtually mythical in a population with comparatively higher rates of suicide and depression, more frequent treatments for substance abuse and mental health, and higher incidences of sexually transmitted infections than ever.[2] Their relationships are shorter and more unhappy than their heterosexual friends. The numbers do not lie: they find only the shallowest and unfulfilled forms of life in their “free world”.

As their own worst enemies, there is undeniably an internalization of the psychopathology of homosexual panic in the gay man. Embarking from an epistemology of his own inhumanity, he is driven to have a keen sense of people from whom he can seek security and validation, in all aspects of life activity (production and work, reproduction and play). This opens a space not of gay emancipation, but misery. This is because homosexual panic is not a phenomenon simply of bourgeois heterosexual society, but something internal to the gay man himself. The totality of the whole world and its perception of him, the gay man's closet bears the burden of a war fortress, and navigating capitalist society is not simply an external material experience.

Gay political history is not much different from this psychosocial profile. Validity, recognition, and authenticity rule the “Gay agenda”, and this is not simply because gay men are politically opportunistic by nature, but because these things are at the core of their material reality. The gay subject erects its existential monuments and social borders as if it were aware of its own phenomena. He knows history has given him a breath of life, where his kind has otherwise come to know only social death. We've seen the little boy with a big secret grow up and embark on an adventurous navigation of capitalist society, at least in the western, core capitalist nations. He has carved, from that of the straight man, his own social centers, economies, geographies, and reproduction schemata, but also his own strata. Class society has been paramount in molding and shaping gay social organization. The gay man came to understand that he could shape and create his own misery and social death, together with his own history and populace that could live openly, with a particular set of bargains with a capitalism where heterosexuality is still normative. What other choice was there, when unlike the peasant, they would be unable to maintain themselves without recourse to the market? Inevitably, this bargain is not really one at all, there is no element of “choice” for the gay man. He will take any validation, authentic or inauthentic.

And yet a viable “Gay radicalism” has suffered a history of inevitable defeats, retreats, swerves and betrayals. The introduction of Queer Theory (which, despite its intent, existed to voice the defeats and crises of gender politics by separating the certainly correlative Women's and Gay Liberation movements) was more a continuation of the failures of gay politics than any correction of the original problematic. There is little value in rooting a development of capital in a gay history rife with failure and defeat and sparing Queer Theory.

In its stead, we aim here to root the gay man as a historical category in the development of capitalism, and in doing so, we come to the only honest conclusions we can, the conclusions which Queer Theory can not. Gay political history has left a thematic of shame, misery, and defeat in its course, the product of a negative view of the private reproductive sphere and positive view of the gay man as the producer of value within the present framework of society. This essay will send the little boy with the big secret through a series of tests in which he might find a way out from a politics of self-loathing: first, a brief history of gay social and political life, from a limited Western scope and far from as exhaustive or complete as was initially desired, but still as committed to a historical materialist analysis as we can be, we will see the little boy embark on his historical journey. Second, by taking a brief and, yet again, limited, but critical look at what AIDS has meant politically for the gay man, we can see what the little boy does when sentenced to death by society. Third, we will tangentially evaluate and offer a critique of Queer Theory and the thought of Judith Butler, as well as a sampling of queer politics including queer nihilists Baeden and Peter Drucker, author of Warped: Gay Normality and Queer Anti-Capitalism, and attempt to make sense of queer politics in the modern day and what it means for the little boy. Lastly, we will talk about what the little boy has grown up to be, and present a communist politics as the only solution for the gay man's problems today.

Capital, History and the Genesis of Gay Life

Categorically, the “gay” is a phenomenon. Upon closer examination, the formation of homosexuals into such a political, economic and cultural phenomenon was not on the horizon of possibility until the advent of capitalist social relations. That is to say, homosexuality is only unified through history as a behavior because sexuality is only transhistorical as a behavior, an activity. It was not until the introduction of commodity production and the free labor system that the “gay man” emerged. Where the “old regime” co-exists with capitalist development, the gay man favors the new regime. Not because the bourgeoisie favors him over that of the cruel, anachronistic, backward old regime elite, but rather because the free-labor system and market relations favor the self-organization of a gay subject under its political economy.In fleeing from the countryside, what the gay man runs from is the rural patriarch he is inadequate to, by legal denial of the feudal institutions of marriage and fatherhood. If the homosexual is to access the means of life necessary for social existence, urbanization is the process by which they find refuge. In a world where the old regime persisted alongside the new regime and the development of capital, the gay man finds refuge in the latter. This was not because, as clarified above, the new regime of the cities was in principle more tolerant, or that capitalism's progressive elements held at heart some partiality to gay liberation, nor was it a particular or specific fetishism of gay labor, or entirely related to the subordination to reproduction of producers in a similar way as feminized labor. It was the phenomenon of labor itself compounded with the conditions of gay life, that being the development of an abstract and surplus labor as forms of value. It is when the gay man's labor takes the form of a commodity, bought and sold on markets for wages, that he finds a particular blindness to his homosexuality. It is bourgeois society in form, not necessarily content, that led to the emergence of a gay “subject”.

John D'Emilio, an early theorist and activist of gay liberation, once posited that gay people had not always existed. For the purposes of brevity and specificity, and what we are trying to grasp, we will echo him here:“I want to argue that gay men and lesbians have not always existed. Instead, they are a product of history, and have come into existence in a specific historical era. Their emergence is associated with the relations of capitalism – more specifically, its free labor system –that has allowed large numbers of men and women in the late twentieth century to call themselves gay, to see themselves as part of a community of similar men and women, and to organize politically on the basis of that identity” - John D'Emilio [note]John D'Emilio. Capitalism and Gay Identity from Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality edited by Ann Snitow, Christine Stansell, & Sharan Thompson. 1983http://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/readings/demilio_captialismgayid.pdf[/note]

So we will meet at a historical “beginning” somewhere in the early 20th century. Not a single point of departure on a linear history, but an epistemology. “Gay” as itself, for itself, was a rupture in social relations, one that could only come into context with capitalism's more progressive tendencies. No doubt, social life in the past century has led to an unprecedented proliferation of homosexuality: we find gay social life in even the most repressed corners of Uganda and Russia. The reason we emphasize the epistemological and existential features of this is due to the continuity gay social life has with the development of capital, and particularly cycles of urbanization. The gay man, almost as a rite of passage, betrays the rural patriarch of the countryside for the refuge of the city. Cycles of urbanization, however, are not unique to capitalist development, and thus we again emphasize the need for capitalist labor relations to explain the proliferation of a homosexual identity.

The gay man's choice of city is indicative of this. When weighed against measures of “tolerance” and public opinion, the gay man chooses the city, like San Francisco, best offering the amenities of a childless adult.[3] Over half of gay men to this day do not reside where they were raised, but where they move to has more to do with life and interests of an individual estranged from the popular institution of marriage. The concentration of gay men in New York, San Francisco, and the major coastal cities in the US is a phenomenon to which trends correlate more to a simple explanation of urban economics than that of a sexual Renaissance blossoming in the cultural meccas of America. Wherever the gay man goes, there he is. With him, he carries the inadequacies and shame to his family and a whole world behind him. He drowns them in the brightest lights and biggest towers, in a world most adequate to his own separation and alienation.

Even before the great social upheavals that would come with the world wars, which provide for a much more convenient and easy place for historical purposes when talking about the genesis of gay life, homosexuality was subject to state regulation and mandated violence. One important terrain of this is the state’s attempts to regulate immigration in the early 19th century. Under immigration legislation in the first decade of that century, immigrants who had been detected as “perverse aliens” could have their citizenship revoked; among them were many male prostitutes who were fleeing state persecution in Germany and elsewhere. The people undertaking the policing and vetting process that immigrants were often put through were mindful to look especially for any “degeneration” in the masculinity of the men who were systematically evaluated at this time. Degeneration was defined as a theory of immigration policy; with eugenicism in full-swing, ideologically not only would an anti-gay politics be incorporated into state and capital in the 20th century, but also white supremacy as explicit state policy.

The antebellum period, global economic depression and the New Deal gave rise to a series of social conditions that are also at the genesis of a gay history. Hobos and various other social outcasts had their own infrastructure of voluntary labor camps, often positioned near sites of work, where a little bit of money could be made in a short amount of time, and one could be on their way hopping the next train. Conditions in these camps were far from accommodating to a lifestyle of adventure as one might hope; they were stringently policed and surveilled, and also the target of political ridicule, as comics depicted these as oases of homosexual debauchery for subversive elements and foreign agents. This was because cleaning up these camps and increasing within them the social welfare of its inhabitants was a venture of New Deal Democrats. The attacks from the far right had a degree of truth to them: gay men and immigrants alike would take refuge in these camps, among many others.[4]

The post-WWII world thrust the gay man into a world that he was perhaps not ready for. In this era, America saw a popular proliferation of “peacetime” recuperation of what American ideas were. This peacetime took the form a war against gay “ideas” along with communist ones. Gay participation in WWII is a story far from untold, but the social ruptures and restructurings allowed for a new epistemology and “knowing” of gay existence. With WWII as a vehicle, gay men (often enlisted and making new lives for themselves in ports-of-call like San Francisco)[5] experienced a new social freedom empowered by a “be nice to GI's” cultural norm across America, giving them resources and direction where ever needed. The transient nature of this allowed for homosexuality to proliferate across new geographies and economies. Under the guise of permitted “GI drag,” gay life in the military at ports of call existed semi-openly; with it, anti-homosexual policies intensified and shifted, often supported by 'advances' in the medical field, understanding homosexuality as an “illness”. As a result of this medical understanding, psychiatric medical boards could non-controversially discharge those engaging in homosexual acts as “unfit for service.” Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of gay men participated in WWII, and in a time when the US military was setting demands of over 15 million recruits, policies couldn't afford the loss of so many.[6]

After the end of WWII, displacement of GI’s became married to “problems” of human migration in the United States during the antebellum period and before that. Immigration to the United States was underway as always, but there was also massive amounts of migration within America. The veterans with blue discharges were often the most likely to drift, as they struggled to get any resources, much less GI benefits, from the Veterans Administration.

The 1940s and 1950s saw the beginning of what we know now to be the embryos of gay culture, although it did not yet “know itself.” It was in this post-war era that homosexuality was taken out of backroom conversations and placed front-and-center for what it was. The Kinsey Report (1948, On the Sexual Behavior of the Human Male) detonated and shifted paradigms in the way society and its interpreters saw sexuality. The secret was up at a time where history could not pack the homosexual man into a convenient closet, and men who had sex with men would become “gay,” out of a natural human desire to understand and be understood. The problem is history is mediated not just by ideas, but the structures and material world which shapes and molds those ideas. Major shifts in psychology and psychiatry occurred over the 1950s, beginning with the American Psychiatric Association's publication of the first issue of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (or DSM) categorizing homosexuality as a feature of a sociopathic personality pathology. This was to be debated amongst psychiatrists in the era. The '40s and '50s were marked by the coexistence, side by side, of mainstream psychiatrists taking the official APA position that homosexuality was a mental illness, and the braver psychologists like Evelyn Hooker challenging that notion that homosexuality was a clinical category in the first place. Her hard work to change the field would not yield the revision of the DSM for decades, but she gave legitimacy to the homophile movement also working to critique mainstream mental health sciences.Now in their historical infancy, gay men had their most open and honest points of encounter in tea rooms, baths, saunas, and park bushes. By the 1950s, bars and saloons would come to be more open spaces of gay social life, and major metropolitan populaces began to all include their gay sections. This was the material infrastructure which laid a path to a “gay identity” as much as their needs and interactions with existing political economy, the labor market, and productive relations. What would be known as the “homophile movement,” containing communists such as Harry Hay, tried to articulate the latter, but was mostly conservative-oriented, begging for a respectability that was not yet on the table. Defeated and shamed, the victories in this era were won willfully, as the state of things had not been shaped in favor of the gay man. However, the seeds of resistance can be seen as having been planted in this era of gay repression. The gay political class suffered early on a series of defeats and retreats spanning decades, a theme which is an almost constant going forward. Somehow, against and in spite of the raids and witch-hunts, gay social life in the cities managed to bloom in the 1950s and '60s.

The Mattachine Society (and later, the similar lesbian group, Daughters of Bilitis) formed within a historical context in which they were confronted with the limits of a gay political group at the time. Their time with communists showed that the great harbingers of class struggle did not think that the gay movement, whatever it was, had anything to do with the history they sought to facilitate. The Mattachines took instead to a more explicitly bourgeois politics, coupled with a defensive strategy. Bars and other gay spaces could not stay open, even more than a space for politics, and gays needed social spaces in which they could simply see and know each other. It was said that the Mattachines were dedicated to making America know that gay people were just like everyone else, but we find absurdity in that when we are talking about class society. In better terms, the Mattachines were determined to show the ruling class that gays were not a threat. They were also functionally a product of the state's war against their socialization. They served to make spaces of civility and respectability, where the repressive law-and-order apparatuses could not effectively target them. They proclaimed openly that gayness was nothing to be ashamed of, without critically examining whether the gay condition could be separated from this. Here we can see the little boy with the big secret prone to the worst naivete, thinking that proclaiming his humanity would be enough to fulfill it.

It was also in this era of contradiction that we see the state proliferate a popular homophobia, alongside the emergence of a gay cultural infrastructure: the first gay newspapers, magazines, and other media. These could barely withstand monoliths like Newsweek and state-sponsored anti-gay propaganda campaigns aimed at socializing a negative perception of homosexuality in the youth. Significant was the case of One Inc. vs. Oleson, in which the Supreme Court was able to uphold for the first time that “homosexuality was not obscene”, thus showing that the Mattachine Society had made its mark. Jurisprudence alone, however, was not the only source of repression in regards to gay media. John Rechy received very negative reception from critics after his release of “City of Night” in 1963, a gay novel profiling male prostitution and homosexual life in detail. Homophobia, even while degenerating as a legal policy, was being proliferated as a popular and cultural attitude. Nevertheless, “City of Night” became widely read and appreciated, and today is considered a classic in gay literature. Other poets and writers emerged as well. Rather important to this was James Baldwin, and while his homosexuality was always obscured and never “confirmed,” in actuality no one can deny his impact for breaking the ice with Giovanni’s Room. “Gay” was hardly ever a “white thing.”

Also occurring in the post-war boom of industrialization was a recuperation of the old regime, once more in the form of the nuclear family. No longer was capital necessarily blind to labor tainted with homosexuality, and thus the rural patriarch that the gay man runs from has now followed him to urban life. In December 1950, a US Congressional committee released a 21-page report declaring “those who engage in acts of homosexuality and other perverted sex-activities are unsuitable for employment in the Federal Government”.[note]“On the employment of homosexuals and other sex perverts in government”

http://www.mwe.com/info/mattachineamicus/document14.pdf[/note] This was not simply by merit of immorality and illegality, but because homosexuality was seen as a subversive security threat. Thousands were arrested, fired, and prosecuted, and years later the conclusions of this report would materialize into actual policy, by means of an executive order from Dwight Eisenhower banning homosexuals from employment in the Federal Government or its contractors. In the UK, Alan Turing, the hero of WWII code-breakers and Godfather to what would become computer science, committed suicide after persecution and clinical castration. Homosexuals in the west were generally still repressed, often by the same state-apparatuses as communists.

Anti-gay repression in this era came to the forefront in mainstream (or bourgeois) American politics for a brief but telling moment in this historical era with the controversial suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester C. Hunt. Hunt was a former governor who was up for re-election in November 1954. In the summer of the previous year, Hunt’s son, Buddy Hunt, was arrested for criminalized homosexuality (charged as soliciting an officer for “lewd and immoral purposes”). This was quieted at first until the fall when Buddy was prosecuted, and things began to look sour from Senator Hunt’s perspective. It should be noted that despite attempts to publicize and garner media attention of the Buddy Hunt arrest, Hunt was still projected to win the Wyoming Senate election. He was the repeated target of threats from Senate Republicans at the time, led by Senator Joseph McCartney from Wisconsin.

Some attribute the Hunt suicide to be a factor in Senator McCarthy’s political decline, but we’d like to emphasize that Senator McCarthy still maintained a moderate general popularity with his anti-communist base for months following the suicide. A look at Senator McCarthy’s congressional censure (a serious political reprimand and denunciation) the following year, none of his spankings in the Senate were ever done in the name of accountability for the Hunt suicide. Facts lead to some notable conclusions here: Lester C. Hunt feared not the loss of political power, but the shame he would bear on account of his son’s homosexuality, and Senator McCarthy and his bloc in the US Senate could bear no shame for seemingly by extension enforcing anti-gay state policy, explicitly against the junior Hunt and by proxy against the senior Hunt. Lastly, McCarthy simply did not act alone, but with the approval of millions of Americans and with a large and powerful bloc of the Senate. We see what is on paper a suicide, but served the function of an assassination for McCarthy and his gang; but most obvious and clear to us is that America killed Senator Hunt.

Homophobia wasn’t simply a separate part of McCarthy’s anti-communism, but a vitally necessary part of it. Because there was no separating the homosexual from the subversive, no inquiry or investigation into someone’s political leanings was exclusive from that of their sexuality. When homosexuality was reduced to a private, bedroom matter, it could easily be turned into a concern for national security. This would lead to inquiries into homosexuality in most of the branches of the US military.

Gay Liberation

These were quiet murmurs until the explosive radical movements of the late 1960s. Stonewall was not the first, but certainly a sharp turning point, and the emergence of the programmatic narrative of “gay power” and the Gay Liberation Front (henceforth GLF) became the New Left's answer to the constellation of Black Power organizations and militant student organizations of the time. Huey P. Newton's address to Black Panther Party on “the homosexual” was a groundbreaking document. [7] According to Newton, gay liberation could not be contained as a purely self-activated thing: it was a product of much broader social upheavals. In America, a gay movement could not simply arise on its own. It required the context of the mass movements against white supremacy and the militants within these movements who saw the necessity of class struggle in both movements. It is not simply an “intersection” to be drawn up abstractly, but the objective reality of history.

The GLF, with Stonewall as its mighty embryo, was the first gay organization of its kind that called for a critique of the totality, that the existing social order must be overthrown in order to achieve gay liberation. It contributed to the much broader political movement of the era which in turn made it possible. The GLF was successful for two reasons, and listing one without the other would be insufficient. It was neither some pure, spontaneous movement emerging from the social antagonisms of the time, nor was it the willful act of revolutionaries who had inherited organizational experience from the previous waves of anti-war and civil rights struggles. They and the greater constellation of organizations made up of its peripherals and fallout provide us with the most important moment in gay political history.

In France, the FHAR (front homosexuel d'action révolutionnaire) took action in direct defiance of what many communists and feminists of the time wanted. The French Communist Party (PCF), in accordance with its homophobic Stalinism, directed blatant and overt homophobia in their direction. In the FHAR membership included Guy Hocquenghem, a gay fan of Freudo-Marxist Gilles Deleuze (who has some very interesting theories if you can tolerate the rhizomatic abstractions) and also lesbians such as Christine Delphy, who would come to define how the left interpreted the history of women and domesticity for years to come. Forming in 1971, the FHAR had a good amount of the youth and fervor from the French movements in May of 1968, which was needed in order to successfully battle the anti-gay elements of the far left, such as the PCF, who were also in the opinions of many communists today a conduit of counter-revolution at this point in history. Combining this circumstance with the anti-racist politics they held in common with the American GLF, they filled the streets with slogans like “workers of the world, masturbate!” and circulated serious pamphlets that read “we have been buggered by Arabs, are proud of it and we'll do it again.” They cared little for holding class struggle to any “purity” (in more senses than one) and they didn't care what their homosexuality represented to others: they were insistent on being an uninhibited formation.

Gay Italian Marxist Mario Mieli, after exposure to the GLF’s London chapter, would come to be similar figure to Guy Hocquenghem for Italy, returning to Milan to build a gay liberation movement there, with a string of organizations from “Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano” (United front of homosexual revolutionaries) or FUORI (meaning “come out”), to the proposed but perhaps not totally realized NARCISO collective (“nuclei armati rivoluzionari internazionalisti sovversivi omosessuali” roughly translated as “armed cells of revolutionary internationalist subversive homosexuals") more in line with Italy’s far left “Years of Lead” participants. Like Hocquenghem, Mieli was strongly influenced by the analysis of Deleuze, although today his legacy is strongest amongst Queer Marxists while Hocquenghem has been very important to today’s Queer Anarchists and Nihilists. Regardless, Mieli’s 1977 work Toward a Gay Communism remains one of the strongest entries in queer radical history. Mieli located any future gay liberation outside of capitalist society and as an intrinsic part of a broader project of human emancipation. Despite the heavy influence of some sophisticated psychoanalytic theory of his time, Mieli speaks with great clarity about his vision for a future society, and also the misery of the gay ghetto. Mieli also made clear for us the relationship of the gay movement to women and trans people, despite using different language than we might use today: the intent of inclusion and unity with these is clear.[8]The GLF, FHAR, and similar groups made a significant mark not only on the shape of gay politics to come, but on that of revolutionary politics in general. However, gay militancy was rife with one significant error—to the GLF, homosexuality was to be considered a revolutionary characteristic, following the logic that inherent and essential to gayness is the revolt against the nuclear family. Much like their feminist counterparts of the era, political gay liberation took Engels' Origin of the Family, State, and Private Property as something of a key to the kingdom that didn't quite fit. While the emphasis of the abolition of the family is redeeming, revolt against capital isn't some inherent characteristic guaranteed to the dispossessed. To put it more simply, the revolt against the nuclear family had already passed: capital could do away with this “necessity” before long, as we can see it is less needed now than in the 1950s. Ultimately, gay people found themselves in a socioeconomic position in which they could reproduce themselves, while still being excluded from the nuclear family, an exclusion which would soften and gray as years would come. Gay politics would soon take on a form which affirmed the gay man as a producer of value without a critique of that system, both that which made him a producer and made him gay.

As a result of the important period of struggle it came from, gay liberation would soon become itself a form of inauthentic validation by which the gay man is fulfilled by reunification with the capitalist state. Nothing blinds him more from revolution than that which would make his father proud, the feeling that he too is worthy of love. We can argue this inauthentic validation as not simply a critique of the programme of the GLF, but as a definitive feature of the gay politics to come. The idea that homosexuality is in essence revolutionary is incompatible with a materialist understanding of history. Stonewall was indeed revolt, and the GLF were no doubt genuine revolutionaries, and they may have been the first break with a shame-based politics for a more authenticating gay politics. However, assimilation is an inevitable historical development if gay politics does not meet class struggle. There is no way out of assimilation except for the destruction of the society that is to be assimilated to, and for the GLF this was understood. The GLF, unfortunately, were blindly bound to the historical moment that produced them. Fearless and romantic, they dreamed of fucking their way to a new world, and really thought this was possible. Of course, they had no crystal balls, but regardless we now know it did not quite turn out this way. Instead, a compromise won out, small concessions came piecemeal, ghettoization ensued, and AIDS would soon come and destroy everything. The GLF had quite the fallout and variety of post-breakup formations, but for the most part the GLF could not build a lasting gay political tradition that could be carried forth into the new struggles, was revolutionary and was a participant in the class struggle.

In Effeminism we see one of the crudest marriages of gay liberation ideologies with radical politics, and it is an unhappy one. From the Effeminists, we see politics which, on one hand, were a product of their era, that of the New Communist Movement and the new wave of radical feminism, and thus immersed in the tense alignment of those movements.[9] As male radical feminists, they self-deprecated to a point of being preoccupied with male guilt, fully upholding the 70's radical feminist line that all men oppressed all women. On the other hand, they had the most radical and historically specific analysis of a side of gay life, particularly effeminate gay lived experiences. It was a revolutionary and openly communist formation of gay men, something the GLF was specifically not.

Gay patriarchy is indeed a tendency (and a reactionary one) of gay politics from the era of gay liberation to today. Separatism of the gay variety, so-called homonationalism (perhaps best expressed in Alt-Rightist Jack Donovan's “male tribalism”), is the most conceivable misogynist political line of thought because it essentially removes women from the equation entirely. Effeminism is the inversion of this, a self-deprecation which forbids an analysis that is made for both specificity and nuance. Founded by Marxist-Leninist gay men who needed an outlet for the contingencies that brought them together, Effeminism fell to the same trend much of the left did, the downward and degenerating spiral of the micro sect.[10] The Effeminists, gay men themselves, were the first group to claim “independence from Gay liberation and all other Male ideologies”.[9] The analysis, inspired heavily by radical feminism, can be appreciated as well as being able to be seen as somewhat out of tempo. Supporting women's struggles does not imply the need to discount a politics capable of addressing the issues of gay men in their specificity. The Effeminists were fiercely driven by a male guilt and didn't articulate a position from which gay feminists should depart from. If the gay man is truly as oppressed by patriarchy and male solidarity as the Effeminists claim he is, then it should be revolutionary that he considers his short-term benefits with the boy's club against his long-term benefits in its abolition. Women don't need guilt and self-deprecation from male feminists, they need feminist principles which stand on their own. The Effeminists were absolutely correct to try to make a break with “gayness as masculinity,” but they were misguided and confused.

The social activism of the 1970s degenerated into careerism and opportunism, not because of the victories of the gay capitalist class advancing itself, but because of the downturn in the general cycle of struggle in that period. The opportunism of a gay ruling class was not something that could or did assert itself from these struggles in infancy, but rather finds its origins in the defeat and fallout of the more revolutionary elements. Worldwide, as capital started to succumb to a new downturn and crisis, we saw a regression and retreat of class struggle away from mass action that could not possibly be seen from one simple angle (in the US, there was a huge amount of black, gay and feminist struggle that we can speak positively of, that later turned towards terrorism, sub-culturalism, reformism, academicism, sectarianism, nationalism, and reaction.)

As these movements lost their steam and spiraled into inertia at the end of the 1970s, nothing could prepare them for what was to come with the rise of AIDS. But like most history, there is an entry into bourgeois politics born in the shadow of defeat, and in the downfall of the peak struggles of the GLF and FHAR. This entry was a constant feature of gay politics, but AIDS would bring a disaster that can't be described adequately here. Gay politics thus far could be (crudely, for the sake of metaphor) compared to playing a board game, and AIDS wouldn't just be a poor landing on an opponents space which cost the game or made it much more difficult. AIDS was the equivalent of the table being knocked out from underneath the board and the pieces, with all conceptions of reality being thrown in every direction. The devastation meant not simply starting over, but fighting a whole new war.

AIDS

Perhaps before a “homonormativity” could take root, a disease, which by its very name (Gay Related Immune Deficiency, or GRID) was a gay-related disease, would cause panic and hysteria across the capitalist world where the gay man had become diseased. The disease itself wasn't gay, so it could only be assumed that with the onset of GRID that it was the gay man that became diseased. The little boy with the big secret could not hide with a face covered in Kaposi's Sarcoma,[11] nor could he depend on and turn to the naive politics of Mattachines of the decades before. He had made a history of running for his life from a patriarch that could never accept him, to a new regime where compromises could be made, only to find he had to fight there too, and had now ended up bourgeois society's new leper. The pain doesn't end there.The social and democratic gains of the prior period, largely improving public opinion of the gay man, were all virtually reversed or set aside with the outbreak of GRID. After it became AIDS, it may have lessened in its association with homosexuality, but nevertheless, AIDS would continue to destroy the gay man in every sense possible, with no signs of going anywhere. Reduced to less than what he was before, the gay man was “caught in the storm” of a natural disaster that affected many more, but the damage to the gay social and cultural space in society was unlike any other experience.

The AIDS crisis in the gay urban centers of North America was not a pure accident; at great risk of echoing anti-gay voices, AIDS was the punishment for gay homosexuality. Reigning policy consisted of an effort to contain AIDS in a homosexual populace from that of the general, rather than attempts to help the suffering communities. This is characterized by the return of repressive bathhouse raids and the criminalization of other forms of “public” gay sex. Gay social life becomes more than simply diseased but plagued, a sentence worse than the death. The plague meant misery and suffering for those who were to survive it. The state's response was to not have one officially, and Reagan's silence was perhaps more than anyone ever needed to say. The gays would simply die, and if they could be policed and repressed, that would be nothing new anyways.

Militant AIDS activism took turns and inherited tactics from the Gay Liberation movement in some continuity with it, but often had to grapple with political questions of its own, and it was not long before the older generation would die, passing on the historical amnesia contributing to the petrification of struggle to come. The primary aim of these campaigns, led by formations such as ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and Queer Nation, was to attract media attention and raise awareness about the needs of queer people living with HIV/AIDS. Tactically, we see some of the most advanced movements during what was otherwise a downturn; at the same time, the scope and desperation of those who responded politically to the AIDS crisis did not heed the revolutionary rallying call of its predecessors. There was some seriousness taken to the idea that there was no way out of the AIDS crisis without bringing the whole ship, the whole damn world, down with it.

The break with business as usual contained within AIDS activism can be seen in the divisive and controversial politics around Larry Kramer. Kramer was a known figurehead in the gay scene of NYC, he was the author of 1978’s Faggots. Faggots was a piece of early gay literature which did not shy away from explicit displays of the transgressive and decadent aspects of gay urban life. Kramer, much like Faggots, was brutally honest and straightforward, some would say perhaps aggressive and stubborn. After years of being a leader in NGO-driven activism to find a solution to the AIDS crisis, Kramer would go on to found ACT UP after finding that the present state of AIDS activism could not push the political boundaries needed to provide the kind of pressure required to end the crisis.

ACT UP produced what would become the modus operandi of not only AIDS activism, but radical democracy for ages to come, with its championing of “direct action” and a tactical militancy borne of their desperation. Peter Drucker describes it as something “global justice movements are indebted to” [12] and “the largest and most militant wave of LGBT activism since the 1970s.” [13] ACT UP would pose a challenge to the existing LGBT organizations which had for several years already failed gay people. While Kramer would describe ACT UP as “democratic to a fault”, ACT UP can also be understood as something that was centered around tactics. Whether people were fighting for reform or revolution was put aside for advancing a tactical militancy. There was a serious consideration in short moments over whether terrorism was the only option left for the movement,[14] but the group would ultimately maintain a commitment to a nonviolent civil disobedience for its entire existence.[15]

ACT UP seemed to peak in scale and intensity towards the mid-to-late section of the crisis, around 1990. There are two actions for which preparation and participation came on a national scale: a protest at the NIH Headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland, and the 1990 AIDS convention in San Francisco. The latter of these saw a huge media storm leading up to it.[16] Kramer went on interviews calling for a riot. This prompted a number of rumors to circulate and put police on edge, from assassination plots on healthcare bureaucrats, to an armed militia of people with AIDS. Kramer and his militia would turn out not to show up, but the temperature raised around this period had an effect on even the most diplomatic of AIDS activists, like Pete Staley during his speech at the convention, expressed sympathy with his movement’s distrust of bureaucrats and scientists, both seeming to drag their feet on the things that ACT UP believed were needed. Regardless, his speech at the 1990 AIDS convention in San Francisco, combined with the ferocity of the protesters and major strain they inflicted on the Bay Area streets that Pride weekend, showed their movement was one to be taken seriously.

After the turning point of these actions, ACT UP was given a chance to actually administer and develop treatment plans, trials, and the various regulations that affected them. Every AIDS patient can govern, so to speak. However, despite its radically democratic structure, there were a certain set of de facto hierarchies within the organization, particularly the centrality of the Treatment and Data Committee (T&D). T&D was the section of ACT UP which was stacked with most of the AIDS activists who made a name for themselves such as Peter Staley and Larry Kramer. T&D were self-educated experts, sometimes more-so than the bureaucrats they would beckon, on everything from drug policy, law, virology, pharmacology, etc.; they had become autodidacts out of desperation. Debates often ensued over who would get to meet with the mayor, president, etc. The tension in ACT UP at this time is often attributed to trying to balance a commitment to democracy and bottom-up organizing, and strategic considerations when given a seat at the table. By 1992, T&D chose to leave ACT UP to form the “Treatment Action Group”.

Despite their admirable efforts and collective direct-action (we are talking about people who were fighting for their lives), AIDS activism did not go the route of bringing down the social order; instead, the development of antiretroviral drug therapy saw the issue mostly settled within the present state of things. This has caused a suspension and damming up of the AIDS crisis, but it is no coincidence that struggles dried up when life became possible by obtaining very expensive medications thought by some to be toxic even when they did work. We have seen drug therapy become more effective, and new medications have less side effects as well, but the drugs themselves remain among the most expensive in the world. How this happens is a complex process between patents issued by the state, FDA, and the pharmaceutical capitalists maintaining their interests very well, but the explanation of why deserves a class analysis. Gay people (and the rest of the mostly abject AIDS patients) had received a stay of execution by the system, but they were not pardoned of their crime. Their new sentence is a lifetime of medication use which can be heavily priced against them, further solidifying them as the patients no one wants to care for, the people whose health care no employer or state wants to pay for.

However there is a great deal more at play when considering the death of the major wave of AIDS activism, which we can consider the highest expression of a gay politics of its time. Clinton promised a “Manhattan project for AIDS,” as proposed by scientists and activists like Kramer alike. A huge amount of support from leading AIDS activists shifted to Clinton. However no such project seemed to follow. One ACT UP Chicago member, Tim Miller, would recall the view of Clinton as a “savior” to have been “the worst thing to have ever happen to AIDS activist movement.”[17] With bodies dropping right and left and thus taking a major toll on the movement, a great despair overtook many of its most formidable and dedicated activists. Some were so disillusioned that they would take simply trying to find peace in their numbered days. In 1996, the year that HIV antiretrovirals really started to take off and hope could finally be restored, Clinton received a D+ on his AIDS policy report card from POZ magazine.[note]Bob Lederer, Clinton and AIDS: A Report Card, Poz Magazine, November 1st 1996

https://www.poz.com/article/Clinton-AIDS-A-Report-Card-1831-5654[/note] It would appear that Clinton, on the opposite bookend of ACT UP history from Reagan, was only different from his predecessors in the amount of lip-service he paid to the movement. From today we can see a clear consistency with previous cycles of struggle: social democracy is the graveyard of social movements, and despite the increasingly glaring failure of social democracy in the west, there is nothing preventing even the most desperate of movements from following this funerary procession.

The '80s and '90s also saw the inevitable product of the struggles that preceded it: as a result of the history thus far, we saw a time where it was more possible than ever before to be “out”. The little boy with the big secret had fewer places to hide, but also fewer reasons to do so. While the shifts in global capital for the post-1970s period (see below) have run concurrently with the rise of a gay political class, that relationship is not linear or causal, and it would be merely speculative to say it is, as the data for this is not there. AIDS was utterly devastating in ways that only large scale natural disasters are. While the gay bourgeoisie was certainly present and continued to develop, they were dying in great numbers too. In a lot of ways, the disaster prevented the gay man from having much of a politics at all outside of survivalism.

Gay liberation had already retreated from class struggle and moved toward social democracy, and thus a petite bourgeoisification of the struggle via a retreat to academia. Without making a moralization of this, we know this all too well to be where historical movements go to die, so this course is no surprise. However, this same shift was the result of a real political-economic experience for the gay man: just as the free labor system thrust him into existence, a “maturity” had onset from these new conditions.

We have to briefly suspend our historical survey for a discussion that couldn't be avoided in writing this text. Queer Theory emerged mostly against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, but could not offer to it a way out of it politically, and still does not offer this. So it is from this life-or-death vantage point that we embark.

What is a “Queer Theory” and can it be Marxist?

What's wrong with Queer Theory? This will not be exhaustive, as there are indeed many things. Queer Theory depends on a break with the alphabet soup conglomerations (from the common LGBT to QUILTBAG) to try to formulate a political basis for the struggles they have in common. Certainly, gay men have been queers for quite some time. “Queer Theory” is the product of the little boy with the big secret passing through the ivory tower and seeking refuge there. It is not the proliferation of “queerness” as an object of thought or a practical abstraction that is necessarily wrong; what is wrong is not having a critical understanding of methods behind producing these abstractions and the subsequent politics which have been a disservice to gay men.To clarify, by identifying what's wrong with Queer Theory, we don't mean “queer politics” in any great sweeping way, or theory which engages with the queer as a category (although the basis for that should be critiqued as well). By “Queer Theory” we specify a trend in academia (and politics) towards a methodology nearly synonymous with the cultural turn. Queer Theory gave birth to a critique of totality of a kind that does not critique capital as an underlying base. “Class inclusive” intersectionality advances an opposition (some would say, turned fetishism) of all oppressions under capital.

Certainly there can be optimism about building a bridge, even categorically through an abstractly shared “queerness,” between the homosexual and the transgender. To say the gay man does not have a political and social life that shares similar antagonisms as the trans-person would be a gross oversight. To the contrary, we think the trans-person has their own materialist history which while concurrent and related to that of the gay man, could not be done justice here, and therefore the hope is that they too can benefit from this text and are best served by not conflating or attempting to do what there is not space for here.

Queer Theory offers something valuable to the gay man, which is the affirmation that is applied to all of the oppressed. Queer Theory is an interdisciplinary constellation of thinkers essentially characterized by anti-oppression politics which focuses on individual experiences and how this plays out in a social, interpersonal context. The terrain is largely postmodernist, where ideology and culture are examined thoroughly to provide explanation for social phenomenon and construction. Not everything remarked is wrong: Queer Theory certainly offers a critique of the oppression the gay man experiences, but it doesn't make much of an effort to categorize it or relate it to his labor and how it relates to civil society. The most problematic and glaring insufficiency of Queer Theory is its failure to understand gayness as a historical category. Judith Butler, in her Big Think blurb on homosexuality, admits to an epistemological fallacy in “discourse creates homosexuality,” and cannot consistently argue the point she so desperately attempts to uphold, that discourse is the space and possibility of homosexuality that reifies and produces it.[18] This problematically renders the phenomenon of gayness impossible, and the space and possibility in the phenomenon of labor. It obscures a materialist understanding of a history of gay politics.

This isn't a semantic grievance we are making with Queer Theory, as the issue is one of praxis. Judith Butler must reduce homosexuality to a behavior but retains its social context to analyze it: her conception of homosexuality is determined by the discourse of language, and not the relations of social reproduction, or even the discourse of desire and civilization (Freud, Hocquenghem, Baeden, et al). In many ways, Queer Theory is wrong by omission, is silent on active, subjective elements of the phenomena. Homosexuality is thus an objective behavior and not a subjective, life-affirming activity. Marxism is different because it puts the problematic front-and-center, with homosexuality as the relationship that capitalist society has a whole to same-sex behaviors. It is not simply the sum of a billion discourses and conversations through many years of development, but rather the sum of millions of interactions between humanity and nature, through the phenomenon of labor, through war, through all the times where there simply wasn’t time for “discourse,” and ideology was but a thrust behind a sword. Ideology is more than the words which describe it; language always contains its subjective limit and abstract element, and sometimes it cannot adequately describe the ideas which produce it as well as the material process. Homosexuality was not simply “talked” or thought into existence, although that is a factor we don’t wish to neglect; but we emphasize that it was made, it was hammered, it was plowed and it was fought into existence. In much (but not all) of what is known as “Queer Theory” is an allergy to Marx.

Butler ultimately theorizes queerness outside the paradigm of struggling classes, and for this we should not forgive her. This is not because the struggle of the gay man should be subordinated to that of the worker, but rather without this context, he has no essence and faces a huge barrier to understanding his oppression. Frankly, Queer Theorists theorize a queerness that has no grounding in a materialist understanding of the world, but instead finds grounding in the least useful thinking in the academy: post-structuralism. This can provide us with more nuance and interesting abstractions, but the usefulness ends there and thus the so-called “queerness” lacks a material essence separate from the abstractions of the academy, and even if there has come to be a movement of people who call themselves queer, a great deal of them also gay, the origin of the idea itself lies in a purely subjective invention. Gender ultimately has nothing to do with the special ritual of “performance” which Butler fetishizes; rather, its roots lie in the same material basis which gives rise to every facet of our social lives, capital relations and our labor. Gender certainly is older, but the totality described by capital, and a critical analysis from that vantage point, is the only way we can understand it. It is a great historical illiteracy which gave rise to queer theory, and without the correct methodologies we will receive a faulty, inadequate answer to “what is queer.” Regardless, this doesn’t discredit the wide range and contributions contained in Judith Butler’s thought (if her debate with bell hooks were on trial here, her treatment would be much different), but this is based on a sum of her main theses contained in her works like Gender Trouble.

We echo Peter Drucker here, to whom we will return later, and want to narrow the scope a bit to directly engage our friend Judy Butler: “But their abstract championing of 'difference' has rarely engaged concretely with the historiography that sometimes seems to suggest that LGBT history is a one-way street. Queer theorists have too often focused on the production of discourse rather than the social relations underlying it.”[19] This is her greatest insufficiency, and unfortunately it doesn't stop at Butler, but rather represents the dominant trend in most postmodern leftist thought.

"The economic relationships between people, though ostensibly of a purely economic, calculable nature, are in reality nothing but congealed interpersonal relationships. Sociology, on the other hand, in concerning itself only with relationships between people without paying too much attention to their objectified economic form, acts as if everything really depended on these interpersonal relationships or even on the opportunities open to social actions, and not on those mechanisms. What is lost in the gap between them—and this gap is to be understood not topologically, but as something really missing from the thought of both disciplines—is exactly that which was once referred to by the term ‘political economy’.” Adorno[20]

Adorno is useful here against Judith Butler for the same reason that Peter Drucker is: the standpoint of the critique of political economy is superior, and Butler's approach is more like that of the committed sociologist. The idea here is not weigh Adorno against Butler, for the latter has clearly had more contributions to the subject at hand. The problem is one of methodology: the phenomenon of gay life cannot be explained but from the lens of the phenomenon of labor, that which Marx says “mediates the metabolism between man and nature, and therefore human life itself”.[21] In order to navigate civil society and form a new social identity on the basis of this, the gay man had to become an even cheaper commodity than he creates. Labor doesn't just produce commodities, it produces itself and the (queer) worker as a commodity. [22] Sexuality and gender are not experiences simply put through Butler's ideological discourses, they are not simply “performed” as abstractions alienated from beings: sexuality and gender are lived and reproduced through a myriad of self-activities, some of which are done in isolation, some of which form the basis of gay social life, but almost all are immersed in and expressed in the totality of capital. The Butler framework offers a way to understand the ideology and culture of homosexuality and its relation to the world, but divorces it from the material production of life on the scale it needs to be understood at.

There comes a “negative turn” beginning in the early years of the millennium, which some would argue is a clean break from Queer Theory, that does seek to address some of the inadequacies of conventional Queer Theory in describing both queer history and the politics of the neoliberal era. This was first popularized by the controversial Lee Edelman, and then further examined and critiqued by nihilists Baeden. Our Baeden friends (and forgive us for the tragedy that is summarizing their positions) explain that Edelman does not go far enough in his magnum opus No Future, and the author of this piece cannot but agree with them. Edelman restricts a queer anti-social project to the cultural and ideological spheres, while Baedan envisions a project in which is a “queer opposition” to the whole of civil society. We can affirm them here and draw a few lines as well. Baedan goes on to describe how a great deal of the existing “positivist institutions of queerness” (which they designate as the “dance parties, community projects, activist groups, social networks, fashion, literature, art, festivals") reproduce the relations of capital in a “queer” way, which doesn't equate as closely to revolt as it does to the reconciliation of the queer with class society.[23]

A major distinction should be made between the anti-politics of Baedan and the anti-politics of Marxism, in that we are aware that we are inescapably and inevitably political, first and foremost. A pure anti-politics is not conceivable or possible, and only the most advanced and vanguardist sections of the generally oppressed population will ever “embrace” this. Of course, sacrificing your politics for the sake of being sellable to the masses is something we don't endorse either. Marxism provides a politics to end all politics, and in that sense it is essentially anti-political, but in a very political way.

A queer politics cannot be anything that it is not from the vantage of the present, which is entirely consistent with a history of shame, defeat, and failure. There is a romanticism of triumphant revolt in Baedan, fueled by a dangerous unity of purity and negativity. This is ultimately idealist, and therefore the best wishes should be with them. It is worth entertaining the idea that just as they are inescapably political, Baedan's is both a fringe of (and sine qua non to) the “positivist institutions of queerness” which form the material basis of civilization. Between the bricks and molotovs that form Baedan's jouissance and the most imperatively radical pamphlets of queer politics we can produce, we will make history, but it will not be just as we please. We will do so under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. Baedan wants to deny these circumstances or purify their politics of them, which is an impossibility as much as they should be appreciated for what they are. Baedan seeks the absence and negation of capital, but without a viable communist politics they are at best a Bonapartism in the streets by the rule of propaganda.

The above doesn't prevent Marxists from falling into the pitfalls that Baedan actually manages to avoid. Peter Drucker's 2015 “Warped: Gay Normality and Queer Anti-Capitalism” seeks to address a lot of the same questions as this text. However, we want to be clear on our differences in conclusions from those of Drucker. Drucker's general summary of queer theory thus far and the theory on the development of gay politics as we know them from the current vantage point is insufficient. It is indeed a thorough and well-researched work of scholarship. Drucker is, rightfully so, an open critic of the backwardness of queer politics in the Marxist Left; he's not afraid to critique Sherry Wolf's politics, the head of an institution that distributes his books.[24] Drucker depends heavily on rooting the development of the gay middle-class status-post 1970's economic trends in the notion of “homonormativity”. We appreciate what is the best attempt yet to make this period of gay life clearer to Marxists such as ourselves, but we find that the framing of things around the factor of “normativity” obscures the understanding of all the victories and failures of gay politics to be contained within (for better or worse) the confines of class struggle. Drucker here is more Queer Theoretical than Marxist.

It's certainly not beneficial to “reduce” struggles to “class” struggles. This is not what is being asked for here; rather we are calling for a better historical method. Before there were proletarians on this continent, there was the murder of homosexuals and gender non-conformists. What we ask of Drucker here is to take the perspective of the millions and not the millionaires (or any other heads), as what we have today is the result of what millions of everyday gay people did yesterday. Class struggle provides explanations to history, the framework of normality (or normalcy, normativity, etc.) might also be completely off. Why would the ruling class ideology, the domineering ideas of the social epoch, seek to normalize gayness, when it could rather de-normalize bourgeois society as a whole? The latter explanation appears more likely. After all, capital needs only value production to survive; there is truly nothing “abnormal” enough to make the capitalists shake in their boots. Drucker depends heavily on the use of “queer” as a verb, speaking of the “queering” of movements, trade unions, and the various organizations of the left as if simply existing with greater visibility in these contexts will lend us better politics.

“But in a heteronormative society, the statement ‘I am straight’ means both less and more than these other, specific statements. It means less because many people who call themselves ‘straight’ have experienced same-sex attraction or sex. And it means more because it conveys to fellow straights that ‘I’m not one of them’, and conveys to people open to same-sex possibility that ‘I am off limits’. In short, ‘straightness’ is a denial of queer possibility. The question thus arises: in a sexually free society, why would even someone who happened to be engaging exclusively in cross-sex sexual relationships have any need or desire to say, ‘I am straight’? Why would the category even exist?” Peter Drucker [25]

Drucker has only the lens of Queer Theory here with which to see straightness. There can be no critical understanding of gayness without a critique of the world in which gayness arises. We can ask questions about the essence of gayness all day (this is a much more difficult matter) but we can also through history verify easily the essence of homophobia and straightness. Homophobia and straightness are first and foremost a social relationship between so-called, would-be, or have-been straight people; either those who have lived this once or lived it always or lived it never. It is clearly and unmistakably an artifact of class struggle. It is what some would describe as a privilege, but it also might be better described as a wage or a bonus. The origins of this bonus result directly from state-repression and anti-gay violence in the fallout of struggling classes. As an agreement more like that of a wage, straightness gives merit to the straight man but obscures that he is also being burdened by this as well. It is a sad, almost pathetic thing. It should be a problem for straight people as it is for all of humanity because it precludes an unequivocal participation in a struggle for a better humanity which includes them. We know that this relationship bears the same burdensome and miserable essence as the gay man, although for many different reasons. The end result is the same: everyone ends up with inauthentic, fragmented and confused humanity (or lack thereof). A better treason can and should be offered.

Drucker also neglects the rapid rate at which “queer” sections of the class that “do not fit into gay normality” are being quickly subsumed into generalized capital relations, quickly following the dreaded “gay” normality. Time magazine, with its often controversial weekly covers, dubbed trans liberation the “Next Frontier” as Laverne Cox pushes an envelope further. What we are sad to say, with no disregard to the centrality and urgency that trans struggles present us with, is that whatever the horrors brought upon by the gay political class in the form of “normality” will soon come to pass for our trans comrades.

"To queer” as a verb has become the last ditch effort of a little boy with the big secret to flex his pubescent manhood for the world to see, that the betrayal to the old regime and all his faggotry is not irreconcilable with the dominant regime of current social order. That is, the “queer everything” model offers nothing but a redux of its opposite, the deficient “gay.” Drucker closes Warped, a text which truly was a pleasure to examine, with an immensely disappointing conclusion which does not offer much to the gay man other than what might be concluded by reading Gender Trouble and The Communist Manifesto back to back, which gay militants who are indeed still suffering might also closely conclude. This crude and vulgar synthesis of queer theory and Marxism simply comes out insufficient. The “Gay Normality” in essence isn't explained in Marxist terms and to great disappointment. The information contained within Warped is certainly abundant and Drucker does demonstrate the premises of its development. However, he fails to argue why this best describes the situation of a gay politics in their specificity, and more so why this abstraction is Marxist, and therefore historically and categorically correct.

“To that end, a few opening questions: What is the nature of a form of being that presents a problem for the thought of being itself? More precisely, what is the nature of a human being whose human being is put into question radically and by definition, a human being whose being human raises the question of being human at all? Or, rather, whose being is the generative force, historic occasion, and essential byproduct of the question of human being in general? How might it be thought that there exists a being about which the question of its particular being is the condition of possibility and the condition of impossibility for any thought about being whatsoever? What can be said about such a being, and how, if at stake in the question is the very possibility of human being and perhaps even possibility as such? What is the being of a problem?” - Jared Sexton [26]We ask a similar set of questions to the Queer Theorist in Drucker concerning the gay man in any specificity, even if perhaps Drucker, Sexton and this author might each produce different answers. We don't have to turn necessarily towards Marxists or Queer Theorists for which basic and fundamental questions should be raised when concerning “essence”, but methodologically we must be consistent. Queer Theory views essence as a static thing and language as that which shapes homosexual life. Rather, it is homosexuality as an activity that necessitates and shapes the discourse of language. The gay man means a rethinking of the social organization of humanity as a whole, and what it means to be human. And still, we lack politics with which to offer the gay man in any specificity in Drucker's book. It is almost strange the punishment he receives in Drucker's texts. Regardless, Drucker’s text remains perhaps the best examination of gay politics as they exist today. Still, there is not in Drucker’s text a thorough analysis of the relationship between sexuality and labor, and what a Marxist perspective for this means.

Marx, Labor, and Sexuality

To know how to go proceed forward, we must go back to the origins of “the little boy with the big secret” and understand how what once gave us freedom now gives to us bondage, and also a way out. We need to look towards the phenomenon of labor and the critique of the political economy, and this means returning to Marx. Marx thought of labor, humanity, and self-activity in ways that no other thinker had ever done. For Marx, an understanding of labor in a purely waged form was insufficient. Bearing in mind John D’Emilio's thesis framing the origins of gay and lesbian social life in the development of the free labor system, this treatment is rare. Even Hocquenghem and Mieli, likely to no fault of their own, come short of describing the relationship of labor and homosexuality and gay politics.[27] A framework of “desire” or “behavior” to describe the essence of gay social life is insufficient when putting this through Marx’s lens of labor. Labor, to Marx, is more than its mere appearance. Central to the conversation, although in the most limited and insufficient way, is wage labor. However, beyond this understanding, labor is also a means to satisfy physical human need generally. Going further, for Marx, labor is also the life-affirming activities as necessary objects of our imagination, desires, and vision for the world. This broad and meaningful conception of labor is best seen in Marx’s Estranged Labor:“For in the first place labor, life-activity, productive life itself, appears to man merely as a means to satisfying a need — the need to maintain the physical existence. Yet the productive life is the life of the species. It is life-engendering life. The whole character of a species — its species character — is contained in the character of its life activity; and free conscious activity is man’s species character. Life itself appears only as a means to life.” - Marx[28]

Gay social life did not emerge because of its essence as a form of desire, behavior or performance, but as a historically specific form of labor which allowed the meeting of a baseline of needs by the selling of labor-power for a wage. Gay men, contingent on capitalist development in many circumstances, are granted the social space in which to live closeted, semi-closeted or completely “out” lifestyles. Labor is humanity’s interaction with the material world in a far range of activities in Marx’s view. Labor mediates the metabolism between man and nature, and therefore human life itself. Sexuality, like most forms of labor, is no different. Putting aside whatever impact Caliban and the Witch would have on this text (if there were such significant witches at the transition to capitalism, surely these were gay witches from the future!), Silvia Federici describes sexuality here in a rather important context in Why Sexuality is Work:

"It is supposed to be the compensation for work and is ideologically sold to us as the “other' of work: a space of freedom in which we can presumably be our true selves — a possibility for intimate, “genuine” connections in a universe of social relations in which we are constantly forced to repress, defer, postpone, hide, even from ourselves, what we desire” - Silvia Federici [29]

Federici elaborates on this in great detail and with much dissatisfaction for the current situation for sexuality, but the point is that sexuality is somewhat defined in our present historical context by our relationship to the other forms of labor in our lives. Much like the broad sections of humanity under capital, this is a “double-freedom”, a false freedom not much different than wage relations, where we consciously and freely are partners in a relationship by which we sell labor from which others derive profit. The gay man makes his own history, but seemingly not as he truly wills, but according to circumstances transcribed from the past. The fact that gay people are gay, and not homosexual, or beyond that and all things relating to a mediation of sexual activities, has everything to do with the self-activities that are repeated billions of times throughout the day by proletarians, long before the heroes of justice and liberation movements could make their histories. “Gay” is not simply a transhistorical behavior captured through the rise of capitalism, but rather it is the sum of millions of social interactions, mediating the terms of sexual life in a new era.

If the social category of the “gay man” is so entwined with the relationship at its birth, and the world he has made in his image, there is an intrinsic relationship to the emancipation of our labor and the project of gay liberation. No other conclusion can come to mind other than thata the rational solution to the problems facing the gay man is located in a history of struggling classes. This means that if we understand the gay man from the standpoint of labor, his emancipation is already bound to the liberation of black and brown people, women, and as always, other queers. If the gay man has his origins in a system of alienated and commodified labor, then what has grown up from the “little boy with the big secret” is built on an inauthentic validation. Imagine having this grow into a shame and fear-driven monster formed by the object of that particular will and consciousness. A greater freedom, where our life labor is unmediated by the relations of capital, is contained with our challenge to the existing order and potentialities of a world built anew. In short, communism means for the gay man the dissolution of the mediation between his labor and life, and this means the little boy who has become the monster must die. Homosexuality as such a thing that might persist several generations into the future, perhaps after we are all gone, will likely not be mediated according to the “gay” system in place. In this potentiality is where the gay man finds his true freedom, not only from homophobia and heterosexuality, but the separation between what he does and how he lives. Will and consciousness, freedom and emancipation, labor and life, humanity and individual, these are things which frustrate Queer Theorists but are of great interest to the Marxist. Those inclined towards Queer Theory may decide for themselves what matters when we are talking about history, but those of us who choose a Marxist view of gay history do so because it also provides in its understanding of these things a way out of them. Marx, the individual, doesn’t deserve all the credit either, as if he were some champion for gay politics in his time. It is not that we are trying to salvage a gay politics from Marx, but rather arguing that without a materialist understand of gay politics, Marxism in any meaningful sense is incomplete. We need to see in gay politics the potentiality for the kind of robust, multi-terrain projects we saw in the best sections of previous cycles of struggle such as the Marxists behind the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. These immense projects would have immeasurable impacts in their respective contexts. That’s just the beginning of an emancipatory potential arising from gay politics.Communism and fulfillment: Conclusions for a gay politics in the present tense

What can be proposed for the little boys with big secrets? Capital presently favors a gay intellectual laborer who can reproduce himself and unload steady streams of money into high-priced markets. Homosexuality doesn't produce this as a transhistorical feature. Despite this, a sizable gay intelligentsia has emerged. Doctors, lawyers, and teachers certainly are wielders of socially necessary labor, but the gay man's role in consumption, circulation, and spending brings us to a greater understanding of modern capitalism than their roles as producers. This is a major shift that shouldn't be recognized as universal, but it could be said this shift is due to an inevitable reconciliation into the capitalist social order. In his struggle to advance the gay man as the producer of value, the gay man becomes advanced as the consumer of capital. This is not simply because it is what capital has decided, but is in large part what gay people have struggled for through decades of loyal mass commitment to social-democratic politics.