“It is the workers alone who, through their initiative, have vanquished fascism. Through their organization they will crush it. They alone have the right to construct Spain’s new regime.” - La Révolution Espagnole. February 15, 1937

In the wake of the power struggles within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the 1920s, the state of international opposition to official communist leadership was in shambles. What seemed like the last hope of saving the revolutionary leadership in Russia had failed. The Executive Committee of the Comintern and the Central Committee of the party had finally stamped out the last open expressions of opposition. Elsewhere those who continued their fight were threatened with punishments of varying degrees. The 1920s showed the strength of opposition could only be harnessed with unity: something ignored in Russia, where the “left” opposition and “right” opposition failed to unite. However, this was not the case during the Spanish Civil War, which saw the Communist “Left” and “Right” united in opposition to fascism and Stalinist opportunism. The formation of the Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) promised a flourishing optimism for revolutionaries in a period where revolutionary leadership often betrayed revolution itself, while demonstrating the importance of working towards principled unity.

A History of Opposition

Within the Soviet Union, the history of the opposition was a continuous farce. Trotsky refused the possibility of unity with Bukharin’s “rightists”, fearing them more than Stalin’s center. Kamenev and Zinoviev united their New Opposition with Trotsky’s Left under the United Opposition with little success; ending with the complete ousting of the United Opposition’s members within the party leadership. Trotsky finally formed his own International Left Opposition and called for the formation of a Fourth International after a short stint within the International Revolutionary Marxist Centre, finally giving up the notion that the Third International could be saved from within. After defeating all oppositions, Stalin finally turned on Bukharin, accusing him and his program of “supporting Kulaks” and having his supporters removed from their positions. The exact nature of Stalin’s agitation toward Bukharin vary; at times people he assumed to be NKVD agents were surveying him and his family, while phone taps and constant affronts within the party functions saw him mentally worn down. After disbanding the Right Opposition and capitulating to Stalin he still continued to be marginalized, culminating with Bukharin battling with the idea of using his party-issued revolver to take his own life. Unable to bear the thought of leaving his family he went about his business regardless of his marginalization until finally in 1936 he was arrested as the ‘Great Purges’ began. He was accused of various crimes with no evidence; supporting Kulak uprisings, from sabotaging Soviet works to even putting glass into the food of workers. Bukharin denied every charge until his family was arrested, finally, he confessed to whatever charge was given and was subsequently shot in 1938.

Bukharin was not the only leader of the Right Opposition to be marginalized by Stalin. Martemyan Ryutin was born to a poor peasant family in 1890, and after having served in the Red Army for some years he became a leading party official in the 20s. Ryutin refused to follow Bukharin in his capitulation to Stalin and entered into the “Union of Marxist-Leninists” as a militant opposition to the party leadership, writing Stalin and the Crisis of Proletarian Dictatorship: Platform of the "Union of Marxists-Leninists. In this polemic, he stated that only an armed ousting of Stalin and the leadership could save the worker’s state- -in doing so assuring his own death. Validating the very existence of the document was seen as treason; Kamenev and Zinoviev read the platform and were expelled from the party in retaliation for not informing the leadership of its existence. After the Union of Marxist-Leninists was destroyed, Ryutin was arrested and shot, his youngest son was tried and shot, his eldest shot in a prison camp and his remaining family exiled to Siberia for hard labor. With Ryutin’s death the last opposition of the 1920s was gone; what fight the communists of the Soviet Union had started was now thoroughly scattered and left for revolutionaries in other countries to continue.

Unity in Spain

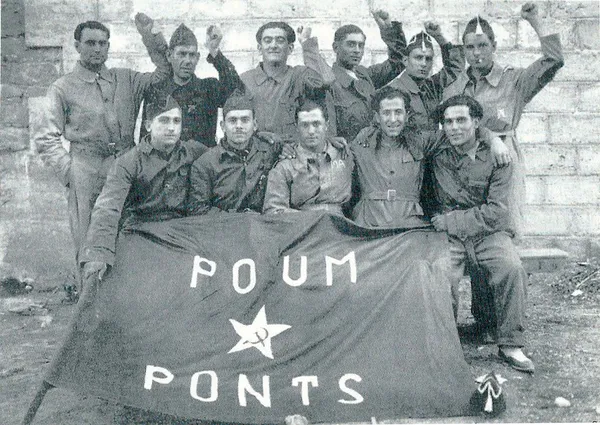

The POUM was formed in 1935, the year before the Spanish Civil War began, by revolutionaries from vastly different backgrounds. Andreu Nin had been a loyal follower of Trotsky since his time long stay in the Soviet Union during the 20s where he found himself deeply rooted in the Left Opposition and became instrumental in the formation of the (Trotskyist) Communist Left of Spain (ICE). As Trotsky advised the leadership, the Communist Left began to engage in entryism into the youth wing of the (Stalinist) Communist Party of Spain (PCE). This strategy was outlined in a letter to Andres Nin in 1931:

In principle, the question of the official party is posed differently, since we have not renounced the idea of winning to our side, the Comintern, and consequently each of its sections. It has always appeared to me that many comrades have underestimated the possibility of the development of the official Communist party in Spain. I have written you about this more than once. To ignore the official party as a fictitious quantity, to turn our back on it, seems to me to be a great mistake., On the contrary, with regard to the official party we must stick to the path of uniting the ranks. Still, this task is not so simple. As long as we remain a feeble faction, this task is in generally unachievable. We can only produce a tendency toward unity inside the official party when we become a serious force.

The leadership of the Communist Left saw this as a dead-end maneuver that would not garner real progress for them, beginning their break with Trotsky and the 4th International. After some time Nin entered into talks with Joaquín Maurín, the leader of the Workers and Peasants’ Bloc (BOC) which had been affiliated with Bukharin’s International Communist Opposition. Outraged at this, Trotsky claimed Nin to be a “traitor communist” and that if Nin had followed his advice, the Communist Left of Spain would have held the status of leaders of the proletariat in Spain, under the discipline of the Fourth International. He smeared the newly formed POUM as a “confused organization of Maurin – without program, without perspective, and without any political importance.”. The POUM now stood as the sole independent communist leadership in Spain and immediately began fostering working class support, building a massive base in Catalonia where the BOC had its origins. While critical of the Comintern Popular Front policy, the POUM still entered into the Spanish front against Fascism in 1936. Internationally, the POUM became officially linked with the International Revolutionary Marxist Centre in London after the destruction of the International Communist Opposition. As the POUM continued its fight against Stalinist opportunism, its membership soared over the years. In July 1936 its membership was roughly 10,000, growing to 70,000 in December 1936, and down to 40,000 in June 1937. This party that Trotsky had previously slated as “without program, without perspective, and without any political importance” was now in direct opposition to the official Stalinist PCE and stood as the second largest proletarian leadership in the Spanish Civil War, refusing to surrender the call for socialist revolution. We can see now the only hope for the Spanish proletariat was revolution and the proletarian dictatorship; the popular government was weak and disjointed, unable to collectivize agriculture or unite the workers into war production at a level that could rival the international support of the Fascists. This was a breaking point with the Stalinists in the PCE who refused to support proletarian seizure of state power out of fear it would break the Popular Front, favoring ‘progressive’ reforms to placate the bourgeois elements of the popular government. Spain highlighted the importance of communist unity; the fight for power is meaningless if sought after by a divided working class. One united leadership under a proletarian program can go about building proletarian political power, but this is impossible if the leadership can’t go beyond petty divides. The CNT-FAI and POUM were unified insofar as they called each other “comrades” and fought the same enemies, but this unity was on paper only - true unity is forged through struggle and defined in structure. One class, one leadership. In the case of Spain, the absence of a united class leadership - a leadership that arises from the class struggle but validates itself through fostering the unity of the class itself - doomed the workers’ hopes of liberation.

Oppositions in Opposition

The unification of communist oppositions in Spain saw militants of differing sides united under the shared experience of a communist partisanship - dogmatism cast away and workers’ power the only interest at play. However, this unity was not met with bright smiles from those both within Spain and outside. As was mentioned before, the state of the communist movement was one of deep fragmentation. Splinters were the norm absent the strict organization of the Stalinists that was validated by their connection to international structural support from the Comintern and its mass membership, regardless of its political degeneration. Unity was not a nice fantasy - unity was the only thing that could assure the proletarian leadership rise counter to the bourgeois domination of the front against fascism. We can look now and confidently say the unification of the ‘right’ and ‘left’ within the POUM was good, while others say that the POUM was instead a total sham. This view is dominant among non-Stalinists because of the prominence of Trotsky, who is enshrined today as the level-headed alternative to Stalin’s sloppy and anti-Marxist collectivization. Yet the shared vulgarity of the two is glaring. The denial of the role of the peasantry in constructing socialism within Soviet Russia is one of the most obvious shared traits. The opposition to forced collectivization - either by gun or taxation - was chiefly Bukharin’s terrain (as well as that of Kamenev and Zinoviev) and elaborated in his defense of the New Economic Policy, following Lenin’s prior layout for collectivization. This was met by Trotsky’s Left Opposition with claims of “rightism”. Dogmatic opposition carried over from Soviet Russia with Trotsky into Spain. Regarding the notion of unity the “Left” and the Bukharin centered “Rightists”, Trotsky carried a disdain for the very basis of communist organization, the organizational strength of the unified working class; spitting in the face of Lenin who (as we all know, was the great divider of communists into neat camps!) to deny the possibility of any actual revolutionary action being carried out. This dogmatic senselessness played into the hands of the Stalinists more than anything else. Why fear oppositions when they’re too busy opposing each other? The POUM was slandered on every side; Trotsky claimed they were traitors to communism and the Stalinists claimed they were fascist collaborators. Trotsky lacked an understanding of the conditions within Spain, yet saw no need for differentiation in tactics and pushed the Communist Left into the dead-end of entryism. Trotsky couldn’t bear to admit he didn’t understand the nature of the work that the Spanish communists had to carry out, and when they did not meet his expectations and turned against his supposed wisdom from abroad, he responded with sectarian slander; a petty reaction to what was the natural conclusion to his ham-fisted involvement in Spain.

Yet even after all this, the POUM was willing to allow Trotsky safety within Spain after his exile. They carried a level-headed mentality. As revolutionaries, they were tasked with building the revolutionary leadership. This placed them in mortal danger, as their leadership found out, there is no space for pettiness when death is the certainty of defeat. The only hope for the communist movement was for the oppositions to unite under a central leadership as the POUM had: in Russia unity came too little or too late and all opposition was crushed, in every country during the crisis of proletarian leadership the absence of opposition allowed the official Communist Parties to carry out Stalinism in accordance with the “loyal opposition” of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Without a unified leadership, the proletariat lacks the ability to successfully destroy the bourgeois state and form the proletarian class dictatorship.

Collaboration and Workers Power

The Popular Front saw the unity of all classes through their shared interests in the defeat of fascism, but by 1937 the Spanish Popular Front was of no use for principled communists, as working class support had already been garnered. Notions of direct opposition to the Popular Front began to grow within the POUM. Spanish agriculture mirrored that of Russia, it was formed mostly by small tenant farmers. Like Bukharin, the POUM supported gradual and voluntary collectivization into communal agriculture against the rushed forced collectivization that many in the Popular Front wished for. In other areas, the POUM found itself again clashing with the status quo of the Popular Front, specifically the Stalinists in the PCE. Even before the post-war years of cowardly “loyal opposition” to the bourgeoisie that the Comintern supported all across Europe, the PCE was already lowering its weapons and supporting bourgeois dictatorship, as exemplified by these quotes:

“The struggle of the armed Spanish people against fascism is a struggle that concerns all the workers and all the democrats of Europe and the world.” (José Diaz PCE leader, party broadcast.)“Once victory is obtained, the Communist Party will follow the line of conduct dictated by its fidelity to its promise to support and maintain the Popular Front government, whatever its ideology.” (Dolores Ibárruri, leader of the PCE.)

This betrayal of the call for workers’ power was a direct product of the Stalinists’ capitulation to the bourgeois state and began the long road down full betrayal of dissident Marxists to defend it. The POUM refused to defend such action as Andreu Nin himself stated in a party bulletin; “We are not fighting for the democratic republic. A new day is dawning, which is the socialist republic.” The POUM’s youth wing followed with “Working youth, which has received nothing but ill treatment from the bourgeois republic, are ready to pursue the struggle until the triumph of the proletarian revolution. All of us united, we must continue the struggle with this slogan: ‘Unity of action of the working class. A WORKERS GOVERNMENT. SOCIALIST REVOLUTION.'”. This continued opposition to the PCE led them into direct hostility. The PCE began a campaign of smear tactics against the POUM, claiming that their true loyalty was to Franco and that they were intent on destroying the Popular Front government. Within a Popular Front the elements of workers’ power can either be disjointed or unified. Within the Spanish Popular Front, the unified communists proposed that the workers should cast away the bourgeois leadership and install workers’ power - not popular power. As the POUM stated in the party paper La Révolution Espagnole in February 1936:

“The militiaman with his rifle, the worker with his hammer, and the peasant with his scythe all fight against Spanish fascism and its supporters Hitler and Mussolini, at the same time that they combat the bourgeoisie of their own country. Taking over the factories and the land, they are in the process of constructing the Iberian Socialist Republic. No national or international force can make them deviate for their chosen path.”

The PCE stood as the direct opposite to the POUM’s demands for proletarian power - becoming the guardian of capitalism and the defender of exploitation. They laid down the weapons of class struggle and instead took up the duties of the bourgeoisie’s hatchetmen. Popular power is an ignorant notion that denies the possibility of proletarian dictatorship. While communists can use a Popular Front for their own ends, the nature of the front and the duty of communists within it must never be forgotten - build workers power, garner working class support, and go about the agitation of the working class into establishing the proletarian dictatorship. Communists use the Popular Front for the realization of their own demands, Popular Fronts must not be allowed to use communists for its own end. The POUM never fetishized the role of the Popular Front just as Lenin never fetishized the role of parliaments, and just as with parliaments, the Popular Front reaches a point where the workers’ movement and its leadership will only be hurt by partaking in it.

“The Workers Party of Marxist Unification, the product of the fusion of the Workers and Peasants Bloc and the Communist Left, believes that it isn’t possible to work towards the entry of all Marxists in an already existing party. The problem isn’t one of entry or absorption but of revolutionary Marxist unity. It’s necessary to form a new party through revolutionary Marxist fusion.” - Program of the POUM, 1936The May Day Betrayal

“Last Sunday’s issue of l'Humanité” reproduces an article by Mikhail Koltsov, Pravda’s Madrid correspondent, with the tawdry title of “The Trotskyist Criminals in Spain are Franco’s Accomplices,” where he pours out ignoble slanders against the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). He speculates on the ignorance of the Russian and international proletariats concerning the political position of POUM and the role the latter played in the first days of the revolution and in the period since then, an ignorance caused in large part by the confusion and the more or less voluntary errors published in the Popular Front press — particularly the Stalinist press — concerning the events in Spain.” - The POUM’s Response to ‘Official Communist’ Articles in Pravda and l'HumanitéAfter July 1936 the workers’ militias in Barcelona had full control of the city and Catalonia as a whole. Most militias were loyal to the CNT and after negotiating with the Generalitat, a government was formed. Established as the Central Committee of Anti-Fascist Militias of Catalonia, it consisted of delegates from the trade unions and parties within the Popular Front. The popular government had no power over this formation of workers’ political power. The arms industries within Barcelona were collectivized by the Catalonian government. However, the central government refused to support the industry (under the influence of the PCE) who feared the growing power of the opposition in favor of ‘popular’ unity. These divisions only grew further as time went on. The POUM and CNT shared a line that the civil war and seizure of state power were directly linked as it had been in Russia. In Valencia, the PCE held a conference in collaboration with Comintern delegates and NKVD agents that concluded with the unanimous decision to immediately liquidate the POUM, its leaders accused of being Nazi agents working with Leon Trotsky to overthrow Stalin and the Central Committee - supported by the same 'evidence' of the show trials against the Soviet oppositionists like Bukharin. The popular government began disarming the workers’ militias and liquidating all organs of political power with support from the PCE. In the administrative district, the PCE’s supporters and workers’ militias formed barricades, aiming guns at one another. The militias loyal to the POUM, the Friends of Durruti Group, the Bolshevik-Leninists, and the Libertarian Youth took control of their own areas and after a short while, all factions had barricades of their own. All across the city battled raged between the different sides as utter chaos broke out. After six days of drawn-out conflict and the constant murder of revolutionaries, the CNT-FAI, Libertarian Youth, and POUM had all been defeated in Barcelona, their militants either disarmed and arrested or killed, their leaders in dismay and mostly in hiding or fully retreated to safety.

After the May Days were over, the PCE lobbied the government to delegitimize the POUM and brand the party illegal, which the government gladly obliged. Alexander Orlov, the leader of the NKVD in Spain, ordered his agents to arrest the POUM’s leadership en masse and sent to the small city of Alcalá de Henares, outside Madrid. This included Nin and the rest of the POUM leadership, with the exception of Joaquín Maurín, who had attempted to escape Spain through Aragon before being captured by Francoists in 1936 and was detained until 1944. The exact details of Nin’s death have never been confirmed, however, the Communist Party official and Popular Government Minister of Education, Jesus Hernández, admitted that Nin was tortured to death. "Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the dry method to get results. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin was subjected to the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days, his face was a shapeless mass of flesh.". After Nin’s death and the final purging of the POUM’s leadership, the same tragedy that was occurring in Russia had now occurred in Spain. The communist opposition was murdered and silenced, workers’ power was no longer the mission of the “official” leadership, and the defense of bourgeois dictatorship was now the true goal of those who had decried the oppositionists in the ICO and POUM as ‘traitors’ and ‘reactionary collaborators’.

The Human Cost of Opportunism

As with every part in the history of the workers’ movement, there is a lesson to be learned from the story of the POUM. Just as the Spanish communists learned from the Russian oppositionists’ failures, so too can we learn from the failures of the Spanish communists. The lessons are rather easy to sum up; never surrender the call for workers’ power, the fight for working-class political power never ends regardless of context, and the presence of communists in a Popular Front is not for the purpose of defending bourgeois dictatorship, but for the garnering of power so that once the working class is strong enough the proletarian leadership can cast away the bourgeoisie and conclude in the only way possible - proletarian dictatorship. The PCE turned its guns on the POUM to defend the bourgeoisie, they spilled communist blood to save the bourgeoisie from having their own spilled. In times when Marxism enters a crisis that shakes it to its very core, the legitimacy of revolutionary leadership and the realization of the workers' dictatorship rests on more than the confines of leadership alone, but the Marxist movement as a whole. The world movement and the movements within national confines are linked beyond the veil of promises and action, but by the nature of communism itself - this link carries over into opposition; oppositionists in every country are irrespectively linked by their struggle to save the movement. Just as the workers’ movement is doomed to fail without the world movement, so too is the opposition doomed to fail when it secludes itself to the confines of the nation. The only assured denial of revolutionary change in the movement is the violent oppression of those who dissent, as Nin’s fight ended in the NKVD camp where he met his death. The revolutionaries in the POUM set an example of what militant communist opposition resembles, though their betrayal and murder is made even more bitter by the fact it was at the hands of other ‘communists’. Their deaths stand as both a testament to the monumental crimes of Stalinism and to their movement in general, no different to the workers gunned down in Russia or the militants murdered in Hungary and Bavaria. If the red flag symbolizes the spilled blood of the workers then that same flag carries with it the blood of the revolutionaries who died fighting for their liberation, regardless of who spilled it.

References

POUM, The General Policy of the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) (1936)

POUM, War of National Independence or Proletarian Revolution? (1937)

Schwartz, Stephen, New Perspectives on The Spanish Civil War (2006)

POUM, Saving the Democratic Republic or Socialist Revolution? (1936)

POUM, POUM’s Response to the Articles in Pravda and l'Humanité (1937)

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.