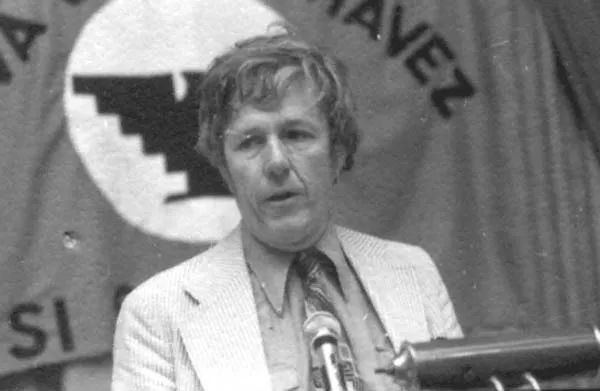

Michael Harrington (1928-1989) was the most important advocate for democratic socialism in the United States in the latter half of the twentieth century. He is widely, and deservedly, recognized for writing The Other America, a seminal exposé of poverty in the United States. However, Michael Harrington was not simply a public intellectual but a political activist who developed a vision to make democratic socialism into a major force in American life. His strategy was to realign the Democratic Party by driving out the business interests and transform it into a social democratic party. This new party of the people would then not only represent the interests of the vast majority and pass genuine reforms, but begin the transition to democratic socialism. Michael Harrington's politics and vision have outlived him and they remain the “common sense” of much of the American left, shaping debates in the organization he founded, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

Life of Michael HarringtonDespite later being hailed as the “Man Who Discovered Poverty,” Michael Harrington's beginnings were anything but impoverished. He was born into a well-off Irish-American and Catholic family in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 28, 1928. When he was growing up, the terms Catholic, Irish, and Democrat were practically synonymous. His immediate and extended family were just as devoted Democrats as they were faithful Catholics and culturally Irish. Despite a brief lapse into revolutionary radicalism in the mid-1950s, Michael himself would maintain his allegiance to the Democratic Party for most of his life.

However, it was the Catholic Church far more than his Irish heritage that shaped Michael Harrington's early worldview. For both religious and financial reasons, Michael's family wanted him to receive a rigorous Jesuit education. He attended local Jesuit schools and later attended Holy Cross College in the 1940s, where he distinguished himself as a brilliant student. Michael absorbed the Jesuits' lessons that “ideas have consequences, that philosophy is the record of an ongoing debate over the most important issues before mankind.”[1] Even after Michael left the Church, a Jesuit spirit remained in his later Marxist writings. In his youth, his social and economic ideas were in line with Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, which condemned unbridled capitalism and displayed concern for the condition of the working class.

After graduating second in his class at Holy Cross in 1948, Michael went to Yale Law School. His father hoped that he would pursue a career in law, but Michael had dreams of becoming a poet. After less than a year at Yale, he was accepted into the University of Chicago's program for English literature. During his time in Chicago, Michael was drawn to the city's Bohemian culture where “everyone... had a poem or play or novel in the works.”[2] Amongst these free spirits, he read voraciously in order to grasp ideas and their implications. He also experienced his first crisis of faith and no longer accepted that people could be condemned to hell no matter the offense. This caused the edifice of his Jesuit worldview to collapse. When Michael graduated with a Master's degree in 1949, he not only lacked his religious belief but was now completely unsure about his future. So he returned home to Saint Louis, where he worked as a social worker in impoverished sections of the city. It was during this time of seeing poverty that he had a revelation:

One rainy day I went into an old, decaying building. The cooking smells and the stench from the broken, stopped-up toilets and the murmurous cranky sound of the people were a revelation. It was my moment on the road to Damascus. Suddenly the abstract and statistical and aesthetic outrages I had reacted to at Yale and Chicago became real and personal and insistent. A few hours later, riding the Grand Avenue streetcar, I realized that somehow I must spend the rest of my life trying to obliterate that kind of house and to work with the people who lived there.[3]

He was now determined to do something to fight poverty. However, he did not yet know what. In December 1949, he moved to Greenwich Village in New York City; Bohemia still beckoned him. While in Greenwich Village, he was exposed to left-wing politics. At one of the many jobs he worked, he recalled that “bosses and the workers discussed the Russian Revolution at lunch break.”[4] He still took little interest in those debates, but was starting to pay attention.

When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, he experienced another crisis of faith and became a conscientious objector and rejoined the Catholic Church. His reconversion occurred after reading Pascal and Kierkegaard: “I no longer felt that I could prove my faith, but now I was willing to make a wager, a doubting and even desperate wager, on it: Credo quia absurdum. I believe because it is absurd.”[5] He decided to put his faith into action. From 1951 to 1953, Michael was a part of Dorothy Day's Catholic Worker Movement, which was one of the most vibrant expressions of left-wing Catholicism in the United States. As Michael later observed: “it was as far Left as you could go within the Church.”[6] The Catholic Worker Movement acted to improve the lives of the poor, preached absolute pacifism, and urged its adherents to “live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ."[7]

Michael Harrington not only worked in the soup kitchens and lived his faith, but wrote and edited for the Catholic Worker on labor struggles and poverty in America. He started making public speeches and developed connections to the literary world and the anti-communist left. Then, in 1952, he met Bogdan Denitch, a member of the Young People's Socialist League (YPSL), who saw Michael as a promising recruit. Denitch's instincts were correct: Michael joined the YPSL and left both the Catholic Worker and the Church itself. This time his break with organized religion was permanent.

Almost from the moment that he joined the YPSL, Michael was fighting the Socialist Party leadership. Due to the Cold War, the Socialist Party and its leader, Norman Thomas, accepted prevailing anticommunist consensus and supported the Korean War. Michael Harrington and the YPSL opposed Thomas and began working with Max Shachtman's Independent Socialist League (ISL), which opposed the Korean War. Michael and the YPSL severed ties with the parent body and fused with the ISL in February 1954 to create the Young Socialist League (YSL).

Michael proved to be a major asset for Max Shachtman and the ISL. He wrote and edited for a number of socialist papers on a vast range of topics. In his capacity as an organizer, he traveled widely across the United States to different college campuses to speak and establish contacts. Max Shachtman himself—a former communist and Trotskyist—ended up becoming Michael's most important political mentor. This influence was something that Harrington acknowledged after he had broken with Shachtman in later years. In the dedication to the 1970 work Socialism, he wrote: “Even though I have some serious disagreements with him on issues of socialist strategy, I am permanently and deeply indebted to Max Shachtman, who first introduced me to the vision of democratic Marxism and whose theory of bureaucratic collectivism is so important to my analysis.”[8] Harrington took from Shachtman a deep-rooted anticommunism grounded in the belief that the Soviet Union was a bureaucratic collectivist evil empire. He also adopted Shachtman's politics in other respects: an adaptation to social democracy, alliances with the labor bureaucracy, and support for “realignment” in the Democratic Party. This is not to say that his politics were completely identical to those of Max Shachtman: he was able to expand and develop Shachtman's ideas and diverged with him on secondary issues when necessary.

During the Red Scare era, life on the socialist left was largely confined to small groups on the margins of politics. Michael Harrington wanted to change that. He became open to collaboration with liberals in pursuit of progressive causes. However, Michael believed that this common work would only be effective if socialists had an organization of their own. An opportunity came to regroup the American left in 1956 after Khrushchev's Secret Speech and the near total collapse of the Communist Party USA. Suddenly a new political space on the left opened up, and both the ISL and the Socialist Party hoped to take advantage of it. Realizing their mutual goals, the ISL and Socialist Party fused in 1958. Considering that the Socialist Party was practically moribund, ISL members such as Max Shachtman and Michael Harrington quickly assumed positions of prominence in the organization. The merger left Michael Harrington hopeful that the left finally had its own organization and would soon place its mark on American politics.

As part of a new strategy for socialists, Michael Harrington was no longer concerned with the revolutionary seizure of power, but with pragmatic and “realistic” questions about using the existing institutions to effect change. To that end, he argued that the left needed to support progressives in the Democratic Party to achieve reforms. He also argued that left-leaning members of the labor bureaucracy such as Walter Reuther were not obstacles to the development of class consciousness, but were allies of the left. According to Michael Harrington, the “Reutherites were the genuine, and utterly sincere and militant, Left-wing of American society.”[9]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Michael Harrington also played an active role in the Civil Rights Movement, where he worked closely with important figures like Bayard Rustin. Rustin was a major organizer for the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr's March on Washington. Harrington and Rustin shared Shachtman's vision of allying the Civil Rights Movement with organized labor and the Democrats to create a new majority. As part of this work, Michael wanted to keep the Civil Rights Movement on a moderate course and worked to exclude communists from organizations such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

It was in 1962 that Michael Harrington first rose to national fame with the publication of The Other America. Even though he wrote dozens of articles and published fourteen books on a diverse array of subjects, his name is synonymous with just this one. The Other America was a groundbreaking and moving exposé of poverty in the United States of America. It established Michael's reputation as a respected intellectual and advocate for the poor. The Other America stirred the conscience of people from all walks of life by revealing the grinding poverty that existed in the richest country in the world. As Martin Luther King Jr once jokingly said to him: "You know, we didn't know we were poor until we read your book.”[10] The Other America's impact extended beyond the circles of idealistic students into the corridors of power when it caught the attention of President Kennedy who planned to launch a “War on Poverty.” After Kennedy's death, President Johnson carried on his legacy by expanding the welfare state with his vision of the Great Society. Michael Harrington himself served as an adviser to President Johnson in developing the Great Society programs.

While Michael supported the Great Society, he believed that welfare state could not overcome the contradictions of capitalism: “Capitalism 'socializes' private priorities and is institutionally opposed to any redistribution of the relative shares of wealth. This is related to its propensity for crisis and, ultimately, its self-destruction. In this context, the welfare state is seen as an ambiguous and transitional phenomenon, the temporary salvation of the system, but also the portent of its end.”[11] As we shall discuss later, Michael Harrington believed that it was necessary to go past the welfare state.

As student radicalism emerged, Michael Harrington was hopeful about its prospects to revitalize the American left, provided that it received proper guidance from him. To that end, he served as a mentor to the young radicals of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in developing the Port Huron Statement. The Port Huron Statement was one of the defining documents of sixties radicalism. According to Kirkpatrick Sale, it not only provided coherence to a new generation of students, but “it gave to those dissatisfied with their nation an analysis by which to dissect it, to those pressing instinctively for change a vision of what to work for, to those feeling within themselves the need to act a strategy by which to become effective. No ideology can do more.”[12] Michael Harrington's ideas are quite visible throughout the Port Huron Statement in stressing the necessity of the student movement allying with the civil rights movement and labor unions, realigning the Democratic Party and supporting liberals, and rejecting communism.

However, the Port Huron Statement also condemned American imperialism for instigating the Cold War and rejected visceral anti-communism. Michael Harrington found this abhorrent and was enraged. He had the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), SDS's parent organization, cut off funding to the youth affiliate and changed the SDS office door locks to keep the radicals out. Later, Michael Harrington and the LID board interrogated the SDS radicals in a mini-show trial for being soft on communism. Eventually cooler heads prevailed and a break between LID and SDS was avoided.

For the rest of his life, Michael Harrington regretted what happened and believed that the clash was due to a misunderstanding between two different generations. While Michael acknowledged his lack of diplomacy in handling SDS, he did not believe he was wrong on the larger political issues at stake: “But if I am quite ready to acknowledge my personal failings in this unhappy history, I am not at all prepared to concede political error on all points in the dispute.”[13] Michael admitted that even if he had been more tactful with SDS, it would not have made a difference in the long run: “the conflict was, I think inevitable, and had I acted on the basis of better information, more maturity, and a greater understanding of the differences at stake, that I would only have postponed the day of reckoning.”[14] Ultimately, Michael Harrington's problem with SDS and the New Left was not just that they were “soft on communism,” but that they rejected the moderation and liberalism that were central to his politics. Eventually, the conflict between him and the radicals came to a head with the Vietnam War.

When the Johnson Administration escalated American involvement in Vietnam, SDS played an active role in opposing it. Like SDS, Michael Harrington opposed the war, but the main dividing line between them was over how to oppose it. Michael wanted to keep his lines of communication open with the White House and liberal Democrats because he believed they were vital allies when it came to domestic reform. To Michael, Democratic support for the war was a tragic error and not the symptom of anything deeper. He refused to target the Democrats as complicit in the war because that could only alienate them. To that end, Michael argued that the antiwar movement needed to be kept within proper limits and stay respectable. He therefore opposed militant action, the participation of communists, breaking the law, or anything that would actually end the war. Only when the Democrats were not the ones conducting the war after 1968 and large swaths of the public and the establishment saw it as unwinnable did Michael come out against it, while his allies like Max Shachtman backed the war to the bitter end.

Over the course of the 1960s, Michael Harrington's relations with Max Shachtman became strained due to a number of issues, leading to a split. Aside from differences over Vietnam, Michael remained steadfast in supporting the original vision of Realignment by supporting progressives in the Democratic Party and labor bureaucracy, and he was committed to winning over moderates in the New Left. By contrast, Shachtman uncritically supported the AFL-CIO leadership, opposed the New Left tout court and backed the most right-wing Democrats because they were reliably anticommunist. The factional fight between Shachtman and Harrington tore the Socialist Party apart. In 1973, Michael Harrington finally resigned from the party.

After leaving the Socialist Party, Michael founded a new socialist organization - the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC). DSOC had a solid base of support among progressives in the labor bureaucracy. Its strategy was to support realignment in the Democratic Party to push it to the left. To that end, Michael Harrington and DSOC supported the Democratic Agenda, a New Deal-style program that was supported by Jimmy Carter in 1976. When Carter was elected, Michael Harrington believed that the Democrats would carry out sweeping reforms similar to FDR or LBJ. Instead, he felt betrayed when the Carter Administration enacted austerity measures and ignored the program of the Democratic Agenda.

Over the course of the 1970s, DSOC grew and began working with like-minded socialist groups such as the New American Movement (NAM). Eventually, NAM and DSOC merged and created the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) in 1982 with Michael Harrington as its preeminent leader. The Reagan years saw crushing defeats on organized labor, attacks on the legacy of the New Deal, and an escalation of the Cold War. To oust Reagan, Michael Harrington and his allies in the labor bureaucracy eschewed any form of independent socialist politics or militancy from below, and instead placed their faith in the Democratic Party. This meant that the DSA stayed aloof from Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, which was probably the most serious Realignment effort in decades, by backing the conservative Walter Mondale. When Reagan secured a smashing victory in 1984, the lesser-evil strategy of “Anybody but Reagan” was shown to be a dismal failure. In a postmortem of the democratic socialist 1984 electoral strategy, Alexander Cockburn concluded:

They must now be footsoldiers in a campaign whose captains are implacably antagonistic to the principles of their constituencies...So in control are the Democratic 'pragmatists' as the pollsters and pundits call them, the ones who argue for party unity at the expense of movement and who propose that the way to beat Reaganism is to denounce its excesses while accepting its premises. The pathos of their opportunism lies in its shortsightedness. As every tactician can attest, the key to defeating Reagan is turnout. But turnout has political content and context. People will not simply vote for Anybody But Reagan; they want somebody who speaks to their interests, who promises them more than they've got and who offers them hope.[15]

It was mere days after Reagan's reelection that Michael Harrington discovered a bump in his throat, which was later determined to be cancer. After a series of operations and surgeries, it appeared that his cancer was gone. By 1987, Michael's doctors told him that he had an inoperable tumor, and he was was given two years to live. During those last years, he continued his political and intellectual work. He finished his second memoir, The Long-Distance Runner, and a testament, Socialism: Past and Future. Still, his condition deteriorated and he quietly passed away on July 31, 1989.

The Limits of Democratic Socialism

From the 1960s until the end of his life, Michael Harrington developed a sophisticated theory of “Democratic Marxism” that he hoped that it would serve as both the ideology and political strategy for democratic socialists and the American labor bureaucracy. Michael believed that the tenets of “Democratic Marxism” would enable socialism to break out of its political isolation, create a new political majority and lead to the creation of democratic socialism. “Democratic Marxism” was all-encompassing, touching on areas ranging from philosophy to imperialism, but here we will discuss merely two of its aspects: Realignment and the Transition to Socialism.

A. Realignment

While Michael Harrington did not originate the idea of Realignment, he did develop it into a full-blown strategy for not only transforming American politics, but as a necessary part of a socialist transition. According to Harrington, realignment was “the only place where a beginning can be made” and he fervently believed that without it, all socialist efforts would ultimately fail.[16] He claimed that the Realignment strategy was based on a Marxist analysis of the changing class nature of American society. He believed that after World War II the social weight of the organized working class had declined. If there was going to be a majority for socialism in America, then the working class couldn't rely only on themselves; it needed allies. As he argued: “There is no single, 'natural' majority in the United States which can be mobilized behind a series of defined policies and programs. Rather, there are several potential majorities at any given time and which one will actually emerge depends on a whole range of factors.”[17]

Michael Harrington argued that the most important ally of the working class was located in the “new class” of scientists, technicians, teachers, and professionals in the public sector of society.[18] The emergence of the new class was a sign that the capitalist economy was “inexorably moving toward collective forms of social life.”[19] In the USSR, China, and Eastern Europe, this collectivist trend took the shape of the new tyranny of “bureaucratic collectivism.” On the other hand, in the United States and Western Europe, collectivism took the form of the welfare state where “markets give way to political decisions... [and] bureaucrats, both private and public, become much more important than entrepreneurs or stockholders.”[14] Harrington concluded that society faced the choice of two possible futures: “these extensions of Shachtman's theories have led me to a basic proposition: that the future is not going to be a choice between capitalism, Communism, and socialism, but between bureaucratic collectivism, advantageous to both executives and commissars, and democratic collectivism, i.e. socialism.”[20] This was Michael Harrington's updated version of Rosa Luxemburg's warning of “socialism or barbarism.”

For Michael Harrington, the issue was not about reversing these collective trends, which he accepted as a given, but whether the future would be democratic or totalitarian. For Michael, the key factor determining the future lay in the contradictory nature of the new class. In the new class, there was the potential for anti-democratic forces prevailing: “With so much economic, political and, social power concentrating in computerized industry, the question arises, who will do the programming? Who will control the machines that establish human destiny in this century? And there is clearly the possibility that a technological elite, perhaps even a benevolent elite, could take on this function.”[21] On the other hand, the new class “by education and work experience...is predisposed toward planning. It could be an ally of the poor and the organized workers—or their sophisticated enemy. In other words, an unprecedented social and political variable seems to be taking shape in America.”[22] For example, the expansion of education was necessary to teach the “new class” of planners and bureaucrats to create new opportunities for social advancement and prestige as part of the established order. However, Harrington argued that students were not destined to “act bureaucratically and use sophisticated means to keep the black and poor in their proper place.”[23] As the 1960s student movements demonstrated, “a school is a dangerous place, for it exposes people to ideas...Increasing education, all the data indicates, means greater political involvement.”[24] This all meant the future political allegiance of the new class was open.

Therefore, the possibility existed of the working class allying with the new class, along with blacks and the poor (Harrington would later include groups such as feminists, peace activists, and environmentalists in this coalition) to build a new majority or the “conscience constituency.”[25] Harrington believed it was only this new majority that could bring real democratic socialist change to America. Eventually, he believed that the components of the new majority would seek political expression. Rather than creating a new third party, Harrington believed it was necessary to realign the Democrats. He argued that the Democrats were a site of struggle for socialists since they not only contained segregationists and capitalists, but also held the allegiance of labor unions, blacks, and progressive sections of the new class. In other words, he claimed there was a contradiction within the Democratic Party between its social base and its racist and capitalist leadership. According to the Socialist Party Platform of 1968: “That the most progressive elements in American life thus belong in the same Party as the most reactionary is one of the most outrageous contradictions in the society. But it is not enough simply to denounce the scandal. We must abolish it.”[26] Michael Harrington was emphatic that socialist work within the Democratic Party “does not constitute a commitment either to its program or leadership...So the democratic Left does not work in the Democratic Party in order to maintain that institution but to transform it.”[27] In 1973, he succinctly described the realignment strategy as “the left wing of realism” because it was only there that the “mass forces for social change are assembled; it is there that the possibility exists for creating a new first party in America.”[28]

Despite the rise of the new class, Michael Harrington believed that the AFL-CIO remained the leading force of Realignment and the new majority. While American labor unions had avoided independent political action in the shape of a labor or socialist party like their European counterparts, he argued that they had actually created one in all but name. In fact, Michael Harrington asserted that the socialism of the American labor movement was actually unknown to most: “there is a social democracy in the United States, but most scholars have not noticed it. It is our invisible mass movement.”[29] Therefore, he concluded that labor unions were not just another interest group in the Democratic Party, but they “had clearly made an on-going, class-based political commitment and constituted a tendency—a labor party of sorts—within the Democratic Party.”[30]

Michael Harrington argued that the first step of Realignment “will not be revolution or even a sudden dramatic lurch to the socialist left. It will be the emergence of a revived liberalism—taking that term to mean the reform of the system within the system—which will of necessity, be much more socialistic even though it will not, in all probability, be socialist.”[31] With a new, robust liberalism as the short-term goal for Realignment, this naturally meant socialists should look to liberals as natural allies. Therefore, the Realignment strategy required patience and playing a long game, but the promised result was the creation of a left-liberal, if not social democratic, party that would take over the Democratic Party and lay the foundations for democratic socialism.

For all its theoretical sophistication, Michael Harrington's Realignment strategy rested on a number of faulty assumptions. Firstly, his contention that the Democratic Party was open to being “captured” by socialist forces was misguided. This position assumed that the Democrats were a loose coalition of diverse interest groups such as labor and capital who were more or less equally balanced. In fact, the Democrats are a capitalist-controlled party representing the interests of more liberal elements among the ruling class. While Michael Harrington is certainly correct that the Democrats do traditionally command the support of a progressive and working-class constituency, this does not make the Democrats the “party of the people.”[32] In fact, labor unions and other progressive groups hold no power in the Democratic Party due to overwhelming capitalist control. Capitalist hegemony in the Democrats allows them to thwart any internal challenge or to co-opt them as the need arises. This is a reality that Michael Harrington never understood.

Secondly, the liberal-labor alliance needed for Realignment was an illusion of Harrington's own imagination. As Kim Moody observed: “Post-World War II liberalism, although embraced by much of the union leadership, was mostly a middle-class phenomenon...As a political current, it never challenged the corporate or private form of property in the means of production, while it rapidly abandoned such New Deal-expanding programs as a national health care system by the early 1950s.”[33] In other words, liberals were not reliable allies of socialists, but were their enemies. To win the support of liberals, Harrington argued that socialists needed to practice moderation and play according to the rules set by the Democratic Party. Since the Realignment strategy saw the Democratic Party as the only political arena for socialists, this led socialists to accept the logic of lesser-evilism and supporting any Democrat, no matter how right-wing, which ultimately thwarted the goals of the entire strategy.

Lastly, the Realignment strategy was doomed because it refused to develop an independent socialist organization. On paper, the Socialist Party viewed themselves as playing a unique role in Realignment as “an independent organization, free of any compromising ties with the old party machines. It can and it will play the role of the most courageous and intransigent force for realignment.”[34] In practice, however, this was never something carried out. As Christopher Lasch argued,

[Harrington] is correct in saying that there are no new social forces automatically evolving toward socialism (which is what "democratic planning" comes down to). Presumably this means that radical change can only take place if a new political organization, explicitly committed to radical change, wills it to take place. But Harrington backs off from this conclusion. Instead he seems to predicate his strategy on the wistful hope that socialism will somehow take over the Democratic party without anyone realizing what is happening. He admits that "there is obvious danger when those committed to a new morality thus maneuver on the basis of the old hypocrisies." But there is no choice, because radicals cannot create a new movement "by fiat." It is tempting, Harrington says, to think that the best strategy for the Left might be to "start a party of its own." But this course would not work unless there were already an "actual disaffection of great masses of people from the Democratic Party.[35]

In the end, Michael Harrington forgot the cardinal lesson of Lenin that "in its struggle for power the proletariat has no other weapon but organization."[36] Without political independence, there was no room for socialists to develop strategies and actions to advance the interests of the working class. Instead, Realignment forced socialists to maintain good relations with liberals in the hopes of reform at the expense of revolutionary militancy from below. The natural end of Realignment and Harrington's democratic socialism was the transformation of leftists into the most loyal servants of the Democratic Party.

B. Popular Front without Stalinism

Instead of through a violent revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat, Michael Harrington believed that socialism could be achieved peacefully through an electoral majority. In formulating a democratic strategy, he drew upon the work of the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci, whom he called “one of the most fascinating thinkers in the history of Marxism.”[37]

Michael Harrington argued that socialists needed to create a counter-hegemonic bloc that comprised a majority of the population, who would have a vested interest in a new order. This counter-hegemonic bloc would win support by promoting a “practical program in a language of sincere and genuine idealism. A politics without poetry will simply not be able to bring together all the different and sometimes antagonistic forces essential to a new majority for a new program.”[38] Harrington argued that the Gramscian “intellectual and moral reform” that socialists needed to undertake involved building upon American traditions, particular Jeffersonian republicanism with its ideals of moral virtue and citizenship: “But I do not think that the Left can afford to leave the civic emotions to the Right. In a profound sense, that is our heritage more than theirs.”[39] The promotion of a new republican ethic would not only Americanize socialism but enlighten people and mobilize them for social change.

For a democratic transition to socialism to be possible, socialists must be able to capture the existing state apparatus from the bourgeoisie. Building on the work of the Marxist theorist Nicos Poulantzas, Harrington argued that the capitalist state was “relatively autonomous” and not the instrument of any single class.[40] He claimed that the classical Marxist position on the state—that it is a machinery of repression in the hands of the dominant class, designed to preserve capitalist rule and existing property relations—was false since it was “tied to the base-superstructure model of society and is flawed for that reason. It metaphorically imagines the government as an inert thing that has no life of its own and is wielded by the 'real' powers residing in the economic base.”[41] Furthermore, he argued that in capitalist society there was no ruling class, merely competing blocs of classes. Due to the great wealth of the bourgeoisie, they naturally exercised greater power in the state than the working class.[42] If socialists could mobilize their counter-hegemonic bloc, then they could win concessions from the state and gradually tilt the state to favor working class interests.

As part of his strategy, Michael Harrington said socialists must utilize the state bureaucracy and undertake a transitional program of structural reforms. He argued that socialists could not dispense with existing bureaucracy since it was essential to the functioning of a modern economy. The problem lay not with bureaucracy per se, but with bad bureaucrats. To serve as a check against bad bureaucrats, he envisioned some form of grassroots control alongside more responsible bureaucrats: “bureaucracy is itself a weapon to be used against bureaucracy.”[43] The structural reforms that he advocated were the socialization of investment; the progressive socialization of corporate property; later, the socialization of private property itself; and finally using taxes as an instrument of socialist change. He believed that this transitional program could be undertaken without any cataclysmic changes since he did not expect violent resistance from the bourgeoisie. Looking to the example of social democratic Sweden, Michael Harrington argued that “it is now possible to have a relatively painless transition to socialization if socialists will only learn how to encourage the 'euthanasia of the rentiers.'”[44] In looking to a positive model for this strategy, Michael Harrington defended the Communist Party's popular front. As he said in a 1976 debate with Peter Camejo:

My policy is very much like the Communist policy in the 1930s. You bet your life it is. I'm an opponent of communist dictatorship and totalitarianism. But while the Socialist Party and the Socialist Workers Party were getting absolutely nowhere because they counterposed themselves to the workers who wanted to vote for Roosevelt, the Communist party of the 1930s was building the biggest, largest movement calling itself socialist in the United States since the days of Gene Debs, and winning leadership in a third of the unions of the CIO.[45]

In other words, he believed in a popular front without Stalinism.[46] However, Michael Harrington's idealization of the popular front is based on a profound misreading of history. During the 1930s, the CPUSA did have a visible presence in unions, black freedom struggles, and anti-fascist coalitions, but this did not come about due to the popular front strategy, but in spite of it. The major successes of the CPUSA in organizing workers occurred before the popular front was implemented when the party experimented with militant united front tactics and still maintained its revolutionary identity. After adopting the popular front strategy, the CPUSA retreated from all that and, in the interests of the Soviet bureaucracy, the Communists ceased all their criticism of the labor bureaucracy, the Roosevelt administration, and liberal organizations. Over the course of the 1930s, the class character of the CPUSA changed as its members took up positions within the labor bureaucracy and clamped down on working class militancy. According to Charlie Post:

Popular Frontism transformed the CP from the main current promoting self-organization, militant action and political independence among workers, African Americans and other oppressed groups into the emerging CIO's bureaucracy's 'point men' in their drive to 'tame' worker and popular militancy and to cement their partnership with the Roosevelt administration.[47]

As a result of the popular front, the CPUSA retreated from its advocacy of communist revolution and ended up as the “left-wing” of the Democrats and the New Deal. The “hidden secret” of why the anticommunist Michael Harrington idealized the popular front was not because it was proof that socialism had mass influence or spoke the language of ordinary people. Rather, he liked the popular front because it was when the communists ceased to be revolutionary and gave up on militant action, self-organization of the working class, and “sectarian” political independence in order to become loyal allies of the labor bureaucracy and liberals. In other words, it was when communists acted like Michael Harrington's ideal of a democratic socialist.

Furthermore, Michael Harrington's popular frontist strategy depends on a fundamental misunderstanding of the state. He is unable to recognize the realities of the state's dependency on both the existing bureaucracy and the needs of profitability. The ability of socialist governments to deliver the type of structural reforms that Harrington advocates such as higher wages and an expanded welfare state depends on higher taxes on capital, both of which ultimately depend upon profitability. If a socialist government seriously pursued structural reforms, then this would threaten the flow of profits and spark resistance from the existing bureaucracy. This means that there are definite limits on the ability of the capitalist state—even if its governing personnel are principled and dedicated socialists—to implement reforms.[48]

Harrington also forgets that a socialist majority in parliament does not equal state power. Rather, the real power in the state resides in its unelected institutions—the military, state bureaucracy, courts—all of which will resist structural reforms and a democratic road to socialism with whatever means are at their disposal. This was shown both when Spain's popular front government and Salvador Allende's socialist government in Chile were violently overthrown in military coups wholeheartedly supported by the bourgeoisie. The reality that no ruling class willingly surrenders its privileges and power was precisely why Marx and Engels said a violent revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat was a necessary strategy for revolutionaries. This is something that Michael Harrington refused to acknowledge. All he can offer is moral appeals to the ruling class and faith that they will play fair with socialists, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Legacy

Since the 2016 election and the campaign of Bernie Sanders, DSA has grown to 55,000 members and become the largest nominally socialist organization in America in over 60 years. The revitalized DSA has seen chapters spring up across the country and its members involved in activities from labor strikes to fixing brake lights to election campaigns (notably the election of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Congress in 2018). It stands to reason that Michael Harrington would be pleased with DSA's growth, but would he still recognize the organization? In some symbolic ways, DSA has moved away from his legacy in a manner that would have horrified Michael Harrington. There are now Marxist study groups who openly talk about Lenin and Trotsky. At its 2017 convention, DSA severed its longstanding ties to the Socialist International and endorsed the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement to end international support for Israel's oppression of Palestinians.[49] Support at the convention for breaking with the Democrats attracted a substantial minority inside DSA. Does all this mean that DSA is abandoning the politics of Michael Harrington and embarking on a new course? In point of fact, Michael Harrington's strategy of Realignment and a democratic transition to socialism remain hegemonic inside DSA.

DSA member Maurice Isserman, a biographer of Michael Harrington, has argued that DSA is growing precisely by supporting Democratic candidates such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Cynthia Nixon: “The two of them did immeasurably more to popularize democratic socialism by acting as the left wing of the possible than any number of purist third-party campaigns, or electoral abstinence, could ever have accomplished.”[50] Isserman argues that those who propose breaking with the Democratic Party are “left sectarians” who embrace “whatever policy and doctrine seems to promise the greatest personal sense of moral purity.”[51]

Isserman himself is a member of the North Star Caucus, one of the many caucuses that have sprouted up in the DSA. Many of the signatories of the North Star Caucus represent the Harringtonite “Old Guard,” who were active in DSOC, NAM, and the labor bureaucracy. The North Star Caucus believes the main goal of the DSA is to defeat the Republicans by supporting the Democratic Party.[52] To accomplish this, the North Star Caucus believes that the Democratic Party needs to be Realigned.[14] Supporters of the North Star Caucus such as George Fish explicitly draw inspiration from Michael Harrington's political vision and understanding of socialism. According to Fish, “Harringtonism is the guiding ideology of democratic socialism in the US” which is characterized by socialism that “fights for free, honest and open elections for achieving socialism based on democratic self-determination and for transformative change for the here and now” as opposed to totalitarian Marxism-Leninism and Trotskyism.[53] Secondly, Fish says Michael Harrington was “correct in seeing the locus for socialist struggle within the Democratic Party, and constituting DSA as the left wing of the Democratic Party,” which he believes was vindicated by the DSA's growth after their involvement in the Bernie Sanders campaign.[14]

While the North Star Caucus are champions of a Realignment strategy in almost identical terms to Michael Harrington, others such as Seth Ackerman have attempted to update the strategy for the twenty-first century. Like Harrington and the North Star, Ackerman acknowledges that the Democratic Party is undemocratic, lacks a coherent program, and that the party leadership is unaccountable to its membership. Instead of simply uncritically supporting all Democrats like the North Star Caucus, Ackerman proposes that the DSA utilize the Democratic Party by running their own candidates on its ballot line. For Ackerman, supporting the Democratic Party ballot line is not a question of principle, but a “secondary issue” and should be utilized “on a case-by-case basis and on pragmatic grounds.”[54] In order for a DSA member to run as a Democrat, Ackerman claims they must adhere to a “democratic socialist” program and be accountable to DSA. In effect, DSA Democrats would function as “a party within a party.” According to Ackerman, his proposal would enable

the Left organize to the point that it can strategically and consciously exploit the gaps in the coherence of the system in order to create the equivalent of a political party in the key respects: a membership-run organization with its own name, its own logo, its own identity and therefore its own platform, and its own ideology.[14]

For all its sophistication, Ackerman's updated Realignment strategy comes up against the same roadblocks as Harrington's original strategy and offers no solution to overcome them.

Whatever their differences, all of the factions in DSA remain formally committed to a democratic socialist road to power. For instance, Jacobin editor Bhaskar Sunkara and leading DSA member Joseph Schwartz favor a strategy that Michael Harrington would have felt quite comfortable with. Sunkara and Schwartz are in favor of an expanded welfare state on the Nordic model, but recognize that “social democracy is good, but not good enough.”[55] Like Harrington, they argue that capitalism undermines social democracy in the long run:

Even if we wanted to stop at socialism within capitalism, it’s not clear that we could.Since the early 1970s, the height of Western social democracy, corporate elites have abandoned the postwar “class compromise” and sought to radically restrict the scope of economic regulation. What capitalists grudgingly accepted during an exceptional period of postwar growth and rising profits, they would no longer.[14]

In line with Michael Harrington's strategy, they advocate building a new majority where socialists “must be both tribunes for socialism and [its] best organizers” along the model of the Communist Party's Popular Front:

Still, the Popular Front was the last time socialism had any mass presence in the United States — in part because, in its own way, the Communists rooted their struggles for democracy within US political culture while trying to build a truly multiracial working-class movement.[56]

According to Sunkara and Schwartz, a new popular front would have a broad base of support necessary to implement “non-reformist reforms” that would weaken capitalism and increase the power of the working class, ultimately leading to socialism. Similar to Michael Harrington, the exact mechanisms of Sunkara and Schwartz's socialist transition remain unclear.

A much more developed strategy of the “democratic road to socialism” has been developed by the sociologist Vivek Chibber. Strangely, Chibber says that the left should look to the early years of the Bolshevik Party as an example of “a mass cadre-based party with a centralized leadership and internal coherence” that is rooted in working-class communities.[57] However, Chibber does not advocate a revolutionary insurrection on the Bolshevik model since he claims it is no longer viable due to the overwhelming armed power of the state. Like Sunkara and Schwartz, Chibber argues that the left needs to pursue a strategy of “non-reformist reforms” that “should have the dual effect of making future organizing easier, and also constraining the power of capital to undermine them down the road.”[14] In the distant future, Chibber believes that socialism will require a “final break” with capitalism, but what that means is left unspecified and vague. For now, Chibber advocates the creation of a reformist Bolshevik Party, and a gradualist strategy.

While the name Michael Harrington is unknown to most of the DSA's new members, his ideas continue to shape the contours of the debates on Realignment, reforms, and democratic socialism. Some such as the North Star Caucus remain unreconstructed Harringtonites, while Ackerman, Sunkara, Schwartz, and Chibber have attempted to make those ideas relevant to the present. Still, none of the Harringtonites have seriously confronted the limitations of Michael Harrington's strategy or how to overcome them. The growth of the DSA's membership opens up the possibility that the organization may decide on a different course than the one envisioned by Michael Harrington. However, at the time of this writing, the future course of the DSA and Michael Harrington's essay remains open.

Conclusion

Michael Harrington's hope was to make democratic socialism a force to be reckoned with in the United States. Whatever his socialist desires may have been, Michael Harrington ultimately reconciled himself to acting as the “loyal opposition” to the powers that be. His realignment strategy meant that he prized tactics of moderation and compromise for fear of alienating potential allies. Realignment was based on a flawed characterization of the Democratic Party as a coalition of equal interest blocs as opposed to a capitalist controlled party, which meant any attempt to “capture” the party was doomed in advance. The requirements of Realignment required kowtowing to liberal prejudices, prizing loyalty to American institutions, and an unquestioning reformist vision. As his conduct proved during the Vietnam War, Michael Harrington's whole strategy acted as a brake and a roadblock to revolutionary action. Still, Michael Harrington's ideas shape debates in the DSA and the wider left. Ultimately, if the American left is serious about fighting for socialism, then they will have to abandon Michael Harrington's politics for those of revolutionary communism.

To Shalon, you mean the world to me.

Doug is currently working on a book on the life of Michael Harrington. His writings can be found here.Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Michael Harrington, Fragments of the Century: A Social Autobiography (New York: Saturday Review Press, 1973), 13. ↩

- Ibid, 35. ↩

- Ibid, 66. ↩

- Ibid, 41 ↩

- Ibid. 17. ↩

- Ibid, 18. ↩

- The Catholic Worker Movement, “The Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker.” The Catholic Worker. http://www.catholicworker.org/cw-aims-and-means.html ↩

- Michael Harrington, Socialism (New York: Sunday Review Press, 1970), vii. ↩

- Harrington 1973, 179. ↩

- Ibid, 129. ↩

- Michael Harrington, The Twilight of Capitalism (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976), 321. ↩

- Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (New York: Random House, 1973), 53-54. ↩

- Harrington 1973, 149. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Alexander Cockburn, Corruptions of Empire (New York: Verso, 1989), 370 and 373. ↩

- Quoted in Robert Gorman, Michael Harrington: Speaking American (New York: Routledge, 1995), 142. ↩

- Michael Harrington, Decade of Decision: The Crisis of the American System (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 291. ↩

- Michael Harrington, Toward a Democratic Left (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1968), 290. For a succinct summary of the new class see Harrington 1968, 282-291 and Harrington 1970, 361. ↩

- Michael Harrington, "The New Class and the Left," in B. Bruce-Biggs, ed., The New Class? (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1979), 24. ↩

- Harrington 1973, 75-76. ↩

- Michael Harrington, The Accidental Century (New York: Penguin Books, 1965), 40. ↩

- Harrington 1968, 290. ↩

- Ibid, 287-288. ↩

- Ibid, 289. ↩

- Harrington 1973, 132 ↩

- Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation, “To Build a Democratic Left, 1968 Platform: Socialist Party, USA,” Archive.org. https://archive.org/details/ToBuildADemocraticLeft1968PlatformSocialistPartyU.s.a/page/n0 ↩

- Harrington 1968, 294. ↩

- Michael Harrington, “Out Beyond Liberalism,” New York Times, March 3, 1973, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/03/03/archives/out-beyond-liberalism.html ↩

- Harrington 1970, 250. ↩

- Ibid, 267. ↩

- Harrington 1980, 321. ↩

- See Lance Selfa, The Democrats: A Critical History (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008). ↩

- Kim Moody, On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 111-112. ↩

- Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation, “A way forward; political realignment in America. political declaration of the 1960 national convention.” and see also Jack Ross, The Socialist Party of America: A Complete History (Potomac Books, 2015), 476-477 ↩

- Christopher Lasch, The Agony of the American Left (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1969), 198-199 ↩

- V. I. Lenin, “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,” Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1904/onestep/r.htm ↩

- Michael Harrington, “Wrestling With the Famous Specter,” The Nation, February 28, 1972, 277 ↩

- Michael Harrington, The Next Left: The History of the Future (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1986), 187. ↩

- Ibid, 191. ↩

- Harrington 1976, 311-312. ↩

- Ibid, 311. ↩

- Ibid, 313. ↩

- Harrington 1968, 146 and 150. ↩

- Ibid. 296-297. ↩

- Michael Harrington and Peter Camejo, “Should Socialists Have Voted for Carter? Part III,” Militant, December 10, 1976, 25, https://www.themilitant.com/1976/4047/MIL4047.pdf24. ↩

- Stanley Aronowitz, The Death and Rebirth American Radicalism (New York: Routledge, 1996), 96 and Stanley Aronowitz, “The New American Movement and Why It Failed,” Works and Days 55/56 Vol. 28, Nos. 1 & 2 (Spring/Fall 2010): 23, http://www.worksanddays.net/2010/File03.Aronowitz.pdf ↩

- I am drawing on the work of Charlie Post here. See Charlie Post, “The Popular Front: Rethinking CPUSA History,” Against the Current. https://solidarity-us.org/atc/63/p2363/ and Charlie Post, “The New Deal and the Popular Front: Models for contemporary socialists?” International Socialist Review. https://isreview.org/issue/108/new-deal-and-popular-front ; Charlie Post, “The Popular Front Didn’t Work,” Jacobin Magazine, October 17, 2017, https://jacobinmag.com/2017/10/popular-front-communist-party-democrats ↩

- See Charlie Post, “What Strategy for the US Left?” Jacobin Magazine, February 23, 2018, https://jacobinmag.com/2018/02/socialist-organization-strategy-electoral-politics ↩

- Juan Cruz Ferre, “DSA Votes for BDS, Reparations, and Out of the Socialist International,” Left Voice. http://www.leftvoice.org/DSA-Votes-for-BDS-Reparations-and-Out-of-the-Socialist-International ↩

- Maurice Isserman, “Who Are You Calling a ‘Harringtonite’?” New York Times, Sept. 13, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/opinion/who-are-you-calling-a-harringtonite.html ↩

- Ibid, 53. ↩

- DSA North Star: The Caucus for Socialism and Democracy, “Statement of Principles,” DSA North Star. https://www.dsanorthstar.org/statement-of-principles.html ; Dan La Botz, “DSA Two Years Later: Where Are We At? Where Are We Headed?” New Politics. http://newpol.org/content/dsa-two-years-later-where-are-we-where-are-we-headed ↩

- George Fish, “Michael Harrington and Harringtonism: A Critical Assessment,” DSA North Star. https://www.dsanorthstar.org/blog/michael-harrington-and-harringtonisma-critical-appreciation ↩

- Seth Ackerman, “A Blueprint for a New Party,” Jacobin Magazine, November 8, 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/bernie-sanders-democratic-labor-party-ackerman ↩

- Joseph M. Schwartz and Bhaskar Sunkara, “Social Democracy Is Good. But Not Good Enough,” Jacobin Magazine, August 29, 2017, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/08/democratic-socialism-judis-new-republic-social-democracy-capitalism ↩

- Joseph M. Schwartz and Bhaskar Sunkara, “What Should Socialists Do?” Jacobin Magazine, August 1, 2017, https://jacobinmag.com/2017/08/socialist-left-democratic-socialists-america-dsa ↩

- Vivek Chibber, “Our Road to Power,” Jacobin Magazine, December 5, 2017, https://jacobinmag.com/2017/12/our-road-to-power ↩