The recent debate hosted on John Riddell’s blog (and reprinted in Cosmonaut) between Eric Blanc and Mike Taber is not only an argument about the details of Marxist intellectual history but one about the correct revolutionary strategy for Marxists today. To summarize the argument, Blanc argues that from the work of the early Kautsky, one can find a strategy for taking power through parliament that is an alternative to the ‘insurrectionism’ of Bolshevism, and that while Kautsky’s method is no less revolutionary, it offers a “democratic road to socialism” that avoids insurrection. Taber, in his response, argues that Blanc is raising a specter when he cites a specific Bolshevik strategy of insurrection, and points of out his own example of the Finnish Revolution saw armed conflict between classes. Furthermore, there are issues with Kautsky’s own politics even in his early pre-revisionist years, such as his wavering on the question of coalition governments and his lack of clarity on the need to smash the bourgeois state. Taber also points out how the Bolshevik Revolution was democratically legitimated and that the Bolsheviks utilized parliamentary elections. The response from Blanc to Taber goes on to make a more detailed argument against a “dual power/insurrection strategy” that is implicit in Taber’s positive view of the Bolsheviks, claiming that one either supports Blanc’s "democratic road" or has an unrealistic belief in “dual power” which is represented by the Marxist Center organization.

The debate is now framed by Blanc as one of dual power/insurrection vs. a democratic road to socialism where a socialist party is elected to parliament. This dichotomy is one established by Nicos Poulantzas in his work State, Power, Socialism. While Blanc does not explicitly mention Poulantzas, his affiliates in The Call promote his work. In State, Power, Socialism, Poulantzas argues that the authoritarianism of Stalinism was incipient in the very idea of dual power as creating a new state, and that the Bolshevik Revolution went wrong with the attempt to take the soviets from a form of dual power to the form of the state itself so as to establish a “class dictatorship” of the proletariat by replacing parliament with the soviets. For Poulantzas, power from below, like the soviets, must be balanced by power from above exercised in a parliament. He argues that instead of trying to build a counter-sovereignty that will take the mantle of state power, socialists must struggle within the state by democratizing its own institutions. On this view, the state is not controlled or ruled by the dominant class, but is a sort of political expression of all classes in their interactions. In the eyes of Poulantzas, socialist politics is a struggle within the bourgeois state for the working class to become the dominant power bloc, or at least a significant faction within it. Power from below has an important role in keeping the parliamentary government from being corrupt and in pushing it to more radical ends.

This general strategy has come to be known as “the democratic road to socialism.” Kautsky’s own work is a reference point for this project, but it was exactly on the issue of the bourgeois state that Kautsky was weakest. It was therefore necessary for his disciple Lenin to reconstruct the Marxist view of the state. For Lenin in State and Revolution, Kautsky was overly vague about the need to smash the bourgeois state and replace it with a workers’ state. Kautsky, in his early works, certainly saw a socialist revolution as something initiated by the election of a revolutionary party, but was ambiguous on the need to smash the bourgeois state and replace it with a workers state, which on its own would transform the nature of the state. Whether there was a real rupture between the bourgeois state and a state based on the organized power of the workers, as Marx argued in "The Civil War in France," was not spelled out by Kautsky.

This is not to say that Karl Kautsky was not a great Marxist with much to teach us, and I do believe that Kautsky’s classic works are essential reading. Kautsky in his prime was certainly a revolutionary, but, unlike Lenin, he never led a successful revolution nor gained, or apparently really attempted to gain, crucial experience as a revolutionary statesman. On the topic of revolutionary strategy, Kautsky issues a good set of basic principles for a party-building strategy (adhering to democratic republican principles and defending Marxism), but the actual nature of revolution and the process of building a revolutionary government are better understood by Lenin. It is absolutely true that Lenin made mistakes, but Blanc would have us dismiss Lenin’s career as a statesman because “really working-class democracy only lasted 6 months.” It is easy to criticize the Soviet Republic as not meeting the ideal of a workers state as outlined in State and Revolution, but this avoids the question in the first place of why bureaucracy, militarization, and restrictions on democratic rights occurred—the country was thrown into Civil War while already in a period of economic collapse.

Any workers' movement taking power, even through fully legal means as in Chile and elsewhere, will have to deal with the problem of civil war, as the Bolsheviks did, and of building a new state. This makes clear the appeal of the “democratic road to socialism”: it avoids having to deal with the fact that any revolutionary rupture—be it the US Civil War, Bolshevik Revolution, Finnish Civil War—will have to deal with an element of catastrophe that may require extreme measures. This is perhaps not a great selling point if we want the undecided masses on board, but it would be cripplingly dishonest to conceal this reality. The history of the 20th century has shown to what barbaric depths the ruling class's fear of socialism will throw society if needed. The strength of reaction, the widespread irrational propaganda of conservatism, and a nascent number of active right-wing paramilitaries in the United States are among many indicators of this historical continuity. Kautsky, although terribly timid in his predictions about the nature of any future revolutionary civil war, recognized in his 1902 book Social Revolution that:

We have also, as we have already said, no right to apply conclusions drawn from nature directly to social processes. We can go no further upon the ground of such analogies than to conclude: that as each animal creature must at one time go through a catastrophe in order to reach a higher stage of development (the act of birth or of the breaking of a shell), so society can only be raised to a higher stage of development through a catastrophe.

Blanc, of course, realizes that a revolutionary government elected to power will face resistance from capitalism and reactionaries. He vaguely calls for whatever is necessary to defend this government, to be achieved in alliance with a mass popular movement, yet he also clearly rejects insurrection. This indecisive vagueness is what is so disturbing. It is exactly armed conflict and insurrection that would be necessary to defend a government genuinely dedicated to undermining capitalism, and we must be conscious and clear about what this implies for and will demand from a socialist party. In a revolutionary situation, the military and police must be splintered and disbanded, the old, corrupt state bureaucracy put under the oversight of the armed and prepared proletariat. The old constitutional order is to be torn down, and representative institutions must be made to embody the mass democracy of the working class. This is what smashing the state entails. This must be clearly articulated and communicated.

If Blanc is merely rejecting putschism or the strategy pursued by the KPD in the March Action, I have no disagreements. Saying that insurrection is off the table while saying you will do whatever is possible to defend a revolutionary government is contradictory if not dishonest, or at least a confusion of legitimate insurrection with putschism. The Finnish Red Guards could have simply given power back to the capitalist class for example, but instead they armed themselves and fought back. They heroically attempted a revolt against the illegitimate authority of the capitalist state, i.e. they attempted insurrection. Any real attempt to make inroads on private property will most definitely find itself coming into armed conflict with the capitalist class, especially in the United States. The working class has to be prepared for this before taking power, which means that a mass party has to have its own defensive wing. As Alexander Gallus shows in his article on Red Vienna, defensive and paramilitary organizations such as the Schutzbund of the Austrian Social-Democratic Party must be successfully organized before the appearance of revolutionary situations, at which point a mass party becomes a major social influence and thus subject to police and fascist violence. While the Austrian Social-Democrats were committed to a strategy that is very similar to Blanc’s conception of a "democratic road to socialism," they had failed to prepare their party and paramilitary organization for a successful civil war against fascism precisely because they refused to utilize insurrection and hone a militant proletarian defense of democracy.

The assumption that bourgeois democracy makes insurrection outmoded and thus allows for a democratic road to socialism also greatly exaggerates the extent that bourgeois democracy is tolerant of subversion by the working class. Just recently a Turkish Communist was elected to office and is being blocked from entering his post. This is just one example of such dirty tricks, and it is easy to imagine that with the ascendance of a mass workers' movement, the capitalist state will shed much of its democratic facade as a workers party grows and threatens the smooth functioning of capitalism. The hope in a "democratic road to socialism" has too much faith in the permanence of bourgeois democracy, not seeing that this is just one method of bourgeois rule. It almost assumes that the democratic parliamentary state is a telos that states head toward, a sort of ideal form that can be assumed. We must not fall for the trap that socialists respecting democracy will necessarily lead to bourgeois rule respecting a socialist movement.

This is of course not a call to abandon participation in elections. Blanc is certainly right that we need to run in elections, and Kautsky tells us much about the correct way to do this. Kautsky, unlike Blanc, did not believe the workers' party should campaign for bourgeois parties like the Democrats. The important lesson from Kautsky and Marxist Social-Democracy is their focus on party-building around a minimum-maximum program. This type of party must run its own independent candidates under the central discipline of a workers' party that has a clear revolutionary agenda. Elections are a means of gathering power and mass support, spreading the Marxist message of the party and consolidating its influence in society. While Mike Taber shows that Kautsky did waver on the issue of coalition governments, Kautsky did, in fact, maintain as a rule that the party shouldn’t enter into coalitions with capitalist candidates, nor enter government. The legislative rather than the executive branch was the target of electoral campaigns so the workers could send representatives to parliament without entering government itself. This is however not the strategy of the DSA or The Call, who believe that the current aim of socialists should be to push debate vaguely “leftwards,” fall behind any candidate who is generally of the left, and campaign for left-Democrats.

Running in elections should not be seen as a way to build workers' power “within” the state. The tendency to see class struggle as an intra-state conflict is a major problem because a socialist movement needs to actually build a counter-sovereignty to the capitalist state, not become integrated into it. It is important to be explicitly clear and honest about this necessary component of socialist revolution and of "building a state within a state," as Kautsky states, one that maintains the working class’s independence. Some, of course, let their fear of integration into the state lead to a complete rejection of electoral politics, which is a mistake. Kautsky’s own original electoral strategy was meant to avoid a situation where the party was elected to merely be a manager of capitalism. The point of elections was to build the party, not maintain parliamentarism, the party serving as a state-within-the-state that had its own working class alternative culture. In other words, it was what those who advocate for base-building call dual power, something Blanc rejects as a strategy. While Blanc does follow Poulantzas in calling for a struggle "from below” to complement the struggle internal to the state, how is such a struggle supposed to be developed without patient base-building, some kind of dual power? Here we fall into the assumption of Rosa Luxemburg’s The Mass Strike that the workers' movement will spontaneously throw up such a struggle which will provide solutions to the problems of the workers' movement. In this sense, there is a strange mix of ultra-left spontaneism in these arguments within the framework of an electoral approach which aims to gradually build workers' power within the state itself without “smashing” the bourgeois state.

Eric Blanc essentially counterposes a strategy of dual power and insurrection to strategy of electoralism. Yet it is necessary to struggle in electoral politics as well as to build a counter-sovereignty to the bourgeois state in the form of a party movement that is willing to defend working class gains, by all means, naturally not limited to, but including, insurrection. The idea of base-building is simply that we need to organize institutions in working-class communities that serve the needs of workers. There are many ideas on how it fits into a broader strategy, yet base-building has been part of what all successful workers parties have done in order to build up strength. As Blanc would likely agree, it is through organization that the working class becomes strong and capable of leading society; but it must be accompanied by the development and eventual leadership of an explicitly Marxist party, one which defends and openly declares our fundamental principles and lessons from history.

Promising a road to socialism without insurrection is a form of wishful thinking, a dangerous hope that we can avoid anything like the catastrophes and difficult situations of revolutionaries in the 20th century. In speaking of a democratic road to socialism, we are only speaking in terms of ideal situations, not actual situations. If a party seeking a "democratic road to socialism" was elected, what would it do if it attempted to nationalize key industries only to be faced by a right-wing coup? One could hope they have sufficient friends in the bourgeois military to avert the coup, which Chavez was able to do with the help of popular mobilization. Yet then one has to deal with the issues of the military becoming a dominant force in the government, bringing with it all the corruption of bourgeois society that has led to massive corruption overtaking the Venezuelan government, something no power from below in the communal movement has been able to check.

More likely is that the military would not side with the socialists, and we would end up with a Pinochet or a technocratic military regime. Do the workers simply stand by? Or do they take up arms to defend their party and legitimate government? One could argue that simply acting in self-defense against a right-wing coup is not insurrection, yet at some point, there must be a decision to engage in military confrontation with the bourgeoisie or not. Not engaging with the concrete reality that a revolutionary state in its infancy will likely see conditions of civil war and that this will necessitate a level of insurrection and militarization that will conflict with some ideals of democracy can only create confusion. The flawed "democratic road to socialism" endorsed by Blanc also expresses a certain kind of faith in the institutions which make up modern democracy, that violent revolutions can be avoided and are simply a product of revolutions against absolutist states. It is an assumption that politics has been civilized, but the rise of right-populism and violence shows this is anything but the case. In fact, the extent to which we actually have functioning democratic processes to work within is severely questionable. As the Harvard Electoral Integrity Project states, the United States has the most corrupt elections in the entire industrialized world, with the majority of primary and general elections being completely rigged.

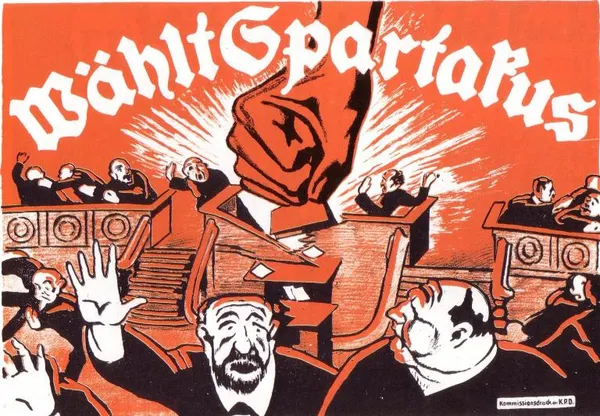

On the question of workers’ government and this slogan, taken up at the Fourth Congress of the Comintern, Blanc sees a move towards a proper recognition of the need for a democratic road to socialism. Yet the Workers’ Government slogan that was taken up was a confusing addition to the strategy of the united front that generally discredited a legitimate strategic turn. The Workers’ Government called for more than joining the SPD in joint struggle: it also called for the KPD to form an electoral alliance with the SPD and even enter government with them. This was to be a sort of halfway-house toward the dictatorship of the proletariat, but in fact only served to create confusion. The KPD and SPD did not have programmatic unity—their politics were inherently at odds at this point, and even if the SPD was part of the labor movement, their politics were the politics of managing capitalism.

To enter government, a workers' party can only go into coalition with those it shares programmatic unity with to enough of a degree that they can stand in unity to fight for the dismantling of the capitalist state and the formation of an actual workers' republic. This basic level of unity was not shared with the SPD, so a ‘Workers’ Government’ between the KPD and the SPD could only be a confused coalition paralyzingly standing in contradiction with itself, with this contradiction either resulting in a breakdown of the coalition or the KPD making shifts to the right in order to accommodate their coalition partners. When the KPD attempted this strategy with the SPD in Saxony in 1923, forming a municipal government in partnership with them, the result was the discrediting of the KPD as they attempted to use the situation as a launching point for taking power. Blanc’s attempt to use the makeshift Workers’ Government slogan as an example of something good in the Comintern doesn’t match up with history, and rather than a “return to form” towards orthodox Marxism, the Workers’ Government was a predecessor to future failures like the Popular Front.

Using elections to advance socialism requires that such efforts are led by a party with an intransigent adherence to the principles of class independence. It also means being aware of the limitation of elections. The party winning an election to the point of being able to take government doesn’t in itself transfer power to the working class: it is merely means of provoking a crisis of the bourgeois state and its legitimacy. Transferring power to the working class requires the successful application of a minimum program that actually leads to a rupture with the existing state institutions. Winning an election can mean the party simply enters into government and manages capitalism, if the party is allowed to enter government at all. Yet winning elections is in fact a tool of great importance, and offers us an unparalleled method of spreading propaganda while breaking up the smooth running of capitalism. The ability of elections to create a crisis of legitimacy that allows for a revolution is not to be ignored or undervalued. However, the point is that a socialist party can only enter into government if it is willing and able to carry out its full minimum program which lays the basis for a workers’ republic. We must not fall into the trap of modern left parties that see getting into government as the only means of accomplishing anything.

The bourgeois state is not broken up overnight either, and a simple parliamentary victory leaves the entire state bureaucracy and military intact. Attempts to engage in even radical democratic reforms will meet resistance from the bourgeoisie and necessitate the decapitation of their armed forces and power. This brings us to the question of the Bolsheviks. While Lenin and the Bolsheviks may not have replaced the bourgeois state with ideal forms (something Lenin would admit), they nonetheless understood that the old state institutions had to go and that relying on experts from the old regime was a setback. They actually dealt with the concrete issue of trying to oversee a rupture from one form of the state to the other, and how this process itself would at times be one of violent class struggle and well as of concessions and retreats. While for Blanc the Bolshevik regime was only a “true workers democracy” for six months and after that was essentially defeated, the Bolsheviks did not even consolidate power and develop some kind of stable regime until 1921. It is assumed that after the Civil War there was no movement within the USSR to extend the gains of the early revolution, or these there were no gains of the revolution left in the first place. It is a view of a workers' state as an ideal that is born as a true democracy, and not an achievement of a protracted process of smashing and replacing the bourgeois state with new institutions governed by working class. In the USSR, this process indeed saw a bureaucracy that would drive the system into capitalism developing and taking hold, but this process was not one that simply began and ended after the Bolsheviks made one certain mistake.

The best of Karl Kautsky is his general strategy of patiently building a revolutionary oppositional counter-sovereignty in the form of a mass party. It is not in his ambiguity on the transition to socialism or his faith in capitalist democratic institutions. On these questions, Lenin was far more clear than Kautsky. Lenin does not theorize a strategy of insurrection but revolution in general, where insurrection is simply a means to an end. His strategy is aggressively unoriginal in its faithfulness to Marx and Engels, but visionary in its ability to organize the working class for revolution in difficult circumstances. On the question of insurrection, Lenin was not a putschist, but simply recognized that the class struggle could and in some cases would necessarily take a military form. The more we deny this, the more we set ourselves up for failure.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.