Today marks the hundred-year anniversary of the beginning of the Winnipeg General Strike. An icon of the Canadian socialist mythology, the Winnipeg General Strike is emblematic of the 1919 Canadian labour revolt and the reformation of the Canadian left between 1917 and 1921. More broadly, it speaks to the spontaneism common to much of the revolutionary left worldwide at the time. It is a lesson in the need for a workers’ party able to command the allegiance of the majority of the working class, with a revolutionary strategy and a clear program leading inexorably to a rupture with bourgeois society.

The Canadian revolutionary left prior to 1917 was small and had relatively little experience in labour struggles, but its message rang loud and clear to the Canadian proletariat. The Socialist Party of Canada (SPC), the first nominally nationwide revolutionary party, was formed in 1904 from a merger of several socialist clubs and sects, mostly concentrated in British Columbia, where it had its largest support.[1] The leading current of the SPC was impossiblist: much like its sister party, the Socialist Party of Great Britain, it rejected all kinds of reformism, which to many of the party’s leading intellectuals included economic struggles. The political struggle was limited to election campaigns, the purpose of which was to educate the working class so that it could ultimately emancipate itself. The role of the party was purely to propagandise, and until 1912 it remained aloof from the trade union movement. Nonetheless, the party held seats in the British Columbia legislature from 1903 to 1912, and did fight for and win important reforms to improve working conditions—even as E.T. Kingsley, one of the party’s primary theoreticians, derided conflicts between employers and workers as mere “commodity struggles” rather than a part of the class struggle itself.[2] This line was essentially a sort of ultra-leftist spontaneism, which in the final case is not much different from reformism: socialists were meant to wait for the final upsurge, which would occur only when the material conditions necessitated it: when the forces of production had developed to the point that capitalism could no longer be sustained, and the socialists, through achieving majority support, could peacefully take power.

This impossibilist line did not sit comfortably with some party branches, especially in Manitoba and Ontario, outside of the SPC’s western heartland. Beginning in 1907, branches gradually broke off from the SPC, until they formed the Social Democratic Party of Canada (SDP) in 1911. The SDP favoured alliances with non-Marxist groups in the labour movement. At the same time, a handful of SPC locals in southern Ontario split because they viewed the party as too reformist; these formed the Socialist Party of North America (SPNA). The SPNA, while anti-electoralist, concluded that its members should join the trade unions whenever possible in order to propagandize among the organized workers.[3] Meanwhile, in 1912, a shift occurred in the SPC leadership, from doctrinaire intellectuals to active trade unionists. The SPC proceeded to win a majority of the executive positions in the BC Federation of Labour,[4] which went on to endorse the SPC’s program.[5]

Thus, on the eve of the First World War, three sects constituted Canada’s Marxist left: the Socialist Party of Canada, the Social Democratic Party, and the Socialist Party of North America. All three were involved in the labour movement in different parts of the country, while the SPC and SDP had some experience with electoral politics. The SDP, despite its rather reformist leadership, had a large number of language federations for immigrants from Eastern Europe, which tended to stand on the left of the party. All three of these sects suffered during the war when their membership depleted and their activities ground to a halt under the weight of war propaganda and state repression.[6] It was only in 1917 that the left was revived, and at the same time split over a single issue: Bolshevism.

Majorities in the SPC and SPNA supported the October Revolution, while the left and right of the SDP progressed towards an all-out split, with the language federations supporting the revolution, while the English section largely began favoring their own party’s liquidation into an analog of the British Labour Party. The SPC, the left of the SDP, and the SPNA began to speak of uniting around the program of Bolshevism.[7] However, despite these talks of the “party of a new type” and the Bolshevik program, the revolutionary left remained spontaneist, and in these formative years worked to build not a mass party that could develop into a counter-hegemonic force in society, but rather a minoritarian “vanguard” party that would intervene in the class struggle in order to propagandize for socialism. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of ordinary workers attended public meetings, went on strike, and called for the nationalization of the means of production. Trade union militants spoke of revolution, and the labour movement, which had fallen nearly silent during the first years of the war, ballooned beyond its prewar levels.[8]

Yet despite clear support for socialist principles among the working class, the revolutionary Marxist sects did not grow to encompass a real contingent of the class. They began working, instead, to influence the working class so that they would rise up and battle for the dictatorship of the proletariat. Marxists in Ontario told striking workers, “we don’t oppose your strike, but you have to take the next step to insurrection!” Many of them seem to have been more familiar with Pannekoek than with Lenin[9], even as they proudly proclaimed themselves Bolsheviks. The eastern labour movement thus remained dominated by conservatives, who went on to dominate the 1918 convention of the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada (TLC). In the West, where the Marxists had a more organic connection to the labour movement,[10] the left won the leadership of the major workers’ organizations and began to formulate a singular strategy for the 1919 TLC convention. This led to the Western Labour Conference in March 1919, where the left held a firm majority.

The resolutions at this conference were explicitly revolutionary: calls for the abolition of private property, for the dictatorship of the proletariat, and for a general strike. The TLC convention was forgotten, and in fact the conference voted to secede from the TLC and form a new, revolutionary industrial union: the One Big Union (OBU).[11] While the OBU has been termed syndicalist by some historians,[12] this charge is bizarre: its instigators came largely from the SPC, which had always been critical of the IWW’s syndicalism and was committed to political action through a revolutionary party.[13] The OBU was not seen by its founders as the primary organ of revolution, but as one weapon among many to be used by the working class in its formation as a class for itself.[14] In fact, it seems that it was not quite clear to the OBU’s founders what its practical function was to be.[15] It was for the rank and file workers, not the political leadership, to wield the OBU for their own revolutionary ends.[16] The SPC had no revolutionary strategy to guide the working class to power, no clear vision of what the tasks of revolutionaries were; as before the war, they saw their activities as consisting primarily of the education of the working class.

Meanwhile, a strike wave was building across the country. 1919 would go down in Canadian history as the most militant year for labour, as nearly 150,000 strikers across the country fought for their rights and the rights of their fellow workers. The strikes of that year can be divided into three categories: first, local strikes addressing the usual issues of union recognition, pay, and work hours; second, general strikes called in support of such local strikes; and third, sympathy strikes called in support of the Winnipeg General Strike.[17] All three of these occurred across the country, despite the East’s more conservative labour bureaucracy.

The most famous of these strikes began in Winnipeg in May. Although the OBU had not yet officially been formed, Peter Campbell insists that “the idea of the One Big Union, which aimed at the linking of socialist theory and trade union protest” was an important factor in the progression of the strike, and further that “it was the interaction between trade unionists and Marxian socialists that made the labour revolt of 1919 as widespread and effective as it was.”[18] In this sense, the SPC was moving towards the “merger formula,” that is, the notion that the socialist movement is the result of a meeting between socialist theory and the workers’ movement. However, it was not able to provide the workers’ movement with a clear strategy for taking power and therefore failed to direct the 1919 labour revolt into a real revolutionary movement.

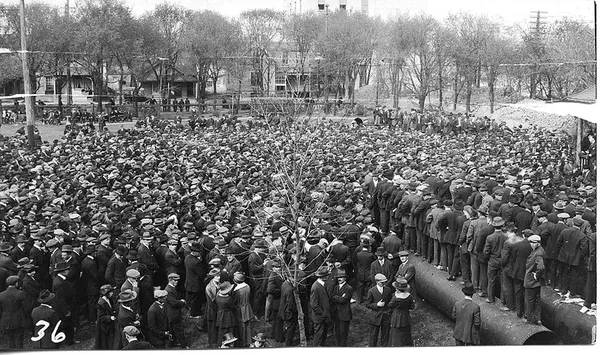

The Winnipeg General Strike was a response to employers’ refusal to bargain with metal and building tradesmen—the metal, mining, and shipbuilding trades were at the forefront of class struggle in 1919.[19] The Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council called a general strike on May 15, with only 500 votes against the proposition versus over 11,000 in favor. Within 24 hours, over 22,000 workers had walked off the job, many of whom were not even unionized; the final number was over 30,000, a clear majority of the city’s working population. A Strike Committee was formed to manage the affairs of the striking workers, and it found itself in control of the city’s labour: workers selectively performed only certain essential jobs in accordance with the Strike Committee’s will. In effect, it planned the city’s economy for the duration of the strike, at least in a partial sense. The police union also voted overwhelmingly for the strike, but at the request of the Strike Committee (in agreement with the mayor) they remained on the job—it was hinted that the army would be brought in to substitute the police if they walked off.[20] Although the striking workers had no goal beyond union recognition and basic wage demands, they had effectively taken control of the administration of the city. Winnipeg, whether the workers were aware of it or not, was ruled (at least in part) by a workers’ council—the Strike Committee.

It is clear, therefore, that the formation of workers’ councils in itself is not a sign of impending revolution or mass class-consciousness. The vast majority of Winnipeg workers had no desire to install the dictatorship of the proletariat. The strike could not advance beyond the immediate aims of the workers without the leadership of a workers’ party with a revolutionary program. The Strike Committee urged workers not to take to the streets, to avoid confrontation with the government. It was the veterans’ organizations, not the Strike Committee, that organized the street demonstrations that did occur.[21] In fact, the SPC-led Vancouver General Strike (one of many across the country called in sympathy with the Winnipeg workers) made more radical demands than those being put forward by the Winnipeg Strike Committee, including the universal recognition of trade unions, the nationalization of cold storage plants, slaughterhouses, and grain elevators (to end the hoarding of foodstuffs), and the enactment of the six-hour workday in industries suffering from large-scale unemployment.[22] In spite of this, the Vancouver strike collapsed not long after the workers in Winnipeg were defeated: the SPC was not willing to continue fighting a battle that it knew it could not win.

The bourgeoisie was not nearly so naïve as Winnipeg’s working class. In opposition to the Strike Committee, Winnipeg’s bourgeoisie formed a “Citizens’ Committee” made up of the city’s businessmen, lawyers, and officials with the purpose of organizing the maintenance of public utilities. The commander of Winnipeg’s military district, Major General Ketchen, was present at the creation of this organization and would collaborate with them throughout the strike. They began circulating their own newspaper, which stated on the front page of the first edition that this was not a strike, but a revolution.[23]

The bourgeois press across the country repeated this sensationalist lie and compared Winnipeg to Soviet Russia. Xenophobia was central to anti-Bolshevism in this period: Eastern European socialists were repressed far more harshly than anglophone socialists, and the Citizens’ Committee pushed a narrative that the strike was being led by these “foreigners.”[24] The strikers and their comrades across the country waged war against the press: shortly after the beginning of the strike, Winnipeg’s six wire-services operators walked off the job, cutting short all transcontinental press communications until direct communication was established between Ontario and Saskatchewan. Telegraphers west of Winnipeg resisted this attempt to circumvent the Winnipeg strike by refusing to handle items originating in Winnipeg or even altering stories directly. The Strike Committee proposed to have the operators return to work if all news items were passed by a special committee for approval, but the bourgeois press rejected the suggestion. The Winnipeg typographers were also pressured to join the strike, shutting down the city’s three newspapers; the Strike Committee began to produce its own daily newspaper in their place.[25] The class struggle had spread to the domain of information: workers and the bourgeois press battled to present their respective narratives of the situation.

The Strike Committee soon found that it had not prepared itself sufficiently for the task of administering a city. When, on the morning after the beginning of the strike, the bread and milk delivery wagons failed to do their rounds, there was widespread panic. The Strike Committee formed a special food subcommittee to organize the distribution of staples and approached the city council to work out a solution to the problem. This cooperation with the bourgeois state is emblematic of a working-class lacking the ability to govern society, with no civic institutions of its own. Once again, the SPC and SDP had failed to prepare the working class to take power.

It was decided, in consultation with the city council and industry, that the Strike Committee would authorize a number of wagons to distribute bread and milk, which would be given placards displaying, “Permitted by Authority of Strike Committee.” Subsequently, restaurants, bakeries, gasoline stations, and cinemas were reopened with the Strike Committee’s authorization, and the work necessary to keep hospitals running resumed. But the mayor, Charles Gray, felt that the necessity of Strike Committee authorization for the essential work of keeping the city running undermined the authority of the bourgeois state. The city council soon pressured the Strike Committee to remove the placards from the milk and bread carts, to be replaced with special cards carried by the cart operators. This was a victory for Mayor Gray and the forces of the bourgeoisie in the battle for legitimate control of civil society.[26] Gray triumphantly stated that now there could be no further misunderstanding “that the legally constituted authority has been taken out of the hands of the civic authority.”[27]

The Strike Committee had demonstrated, even in its first week of existence, that it was incapable of serving as a counter-hegemonic force against the bourgeois state, incapable of serving as the basis for a workers’ republic. This, nonetheless, did not assuage the fears of Canadian and American capitalists, who continued to print sensationalist headlines about the strike.

This was when the federal government sent representatives to Winnipeg. Even as the Strike Committee failed to contest the bourgeoisie’s grip on state power, to remain aloof any longer would signal a crisis of legitimacy for the Canadian state. Gideon Robertson, the Minister of Labour, and Arthur Meighen, Minister of the Interior and of Justice, arrived on May 21. Having already been exposed to the Citizens’ Committee’s narrative, they spoke to Manitoba’s Premier, Tobias Norris, to General Ketchen, and to various other officials. They refused to address the Strike Committee, despite the Committee’s invitation to attend their meeting. They insisted that the Strike Committee send a delegation to meet them the next day instead.

The cabinet ministers and the Citizens’ Committee quickly began collaborating to undermine the strike. Their first target was the postal workers, who threatened to disrupt the postal service nationwide. They issued an ultimatum to the postal workers to return to work within three days or be dismissed. Even before waiting for the expiry of the three days, however, they had begun to gather volunteers to continue the work. All but 40 of the postal workers chose not to return to work and were fired. The railway mail clerks struck in solidarity with the postal workers but soon were forced to return to work or meet the same fate. Some of the fired postal workers asked to be allowed to go back to work and offered to give up their union memberships, but they were not rehired.[28]

In failing to retaliate for the dismissal of the postal workers and letting the bourgeoisie retake control of certain means of production, the Strike Committee demonstrated that it presented no real threat to the “constitutional order.” The working class here was no fighting force struggling to control the means of production. Nevertheless, the government would not be satisfied until the total defeat of the working class. Paranoia over the influence of revolutionaries in the One Big Union surely fuelled this hostility.

Robertson was firmly convinced that the Strike Committee and the OBU were connected, working to bring about revolution in Canada. He was convinced of the need to crush the strike in order to strangle the OBU in its cradle. Although his musings of a conspiracy were fantastical, he was likely correct that the success or defeat of the strike would affect the balance of class power in Canada for years to come. Supporters of the OBU came to the same ultimate conclusions that Robertson did. Meighen, while perhaps not sharing Robertson’s paranoia, was equally convinced of the need to crush the general strike, as its success might encourage the formation of vast industrial unions, capable of calling general strikes at a moment’s notice.[29]

The bourgeoisie soon turned its gaze to the police service, which was sympathetic to the strikers. They presented the police with an ultimatum: to renounce their connections to the unions and pledge their allegiance to the state, or be dismissed. In the end, only a small minority of the police force elected to take the vow. The city council was placed in a delicate situation at this point because to carry out their threats, they would have to empty the streets of the police force. The Citizens’ Committee and the government forces immediately founded a special police force and failed to follow up on the ultimatum.

In response to the introduction of the special police, the Strike Committee ended the distribution of bread, milk, and ice. However, the Citizens’ Committee organized volunteers to distribute staples to the population, with the protection of the special police. Meanwhile, the bourgeoisie continued to build up its special police force. Shortly after this, the 240 members of the official police force who refused to sign the pledge were dismissed. The regular head of police was additionally sent on leave. The armed wing of civil society had been almost fully replaced, in another victory for the bourgeoisie in the contest for legitimate authority.

The special police force had practically no training, and through its brutality broke the tense peace that had hitherto persisted in the city. They attempted to break up crowds listening to public speakers and were quick to resort to the baton or even the firearm. Brawls between strikers and police became relatively common occurrences.

As sympathetic strikes spread, the bourgeoisie scrambled to find a peaceful conclusion in their own favor. They proposed to negotiate with the craft unions, the bureaucrats of which were opposed to the OBU’s radicalism and industrial unionism. This divided the Winnipeg workers’ movement, and the strikers were split over the issue of whether to settle on these terms. The Strike Committee opposed this move against it, but if it could not maintain control of the skilled labour force, then the strike would disintegrate. In this moment of weakness, in the early hours of June 17, the government made its move against Winnipeg’s radicals.

Even without having charged them, state forces swiftly swept up the radical strike leaders and placed them in prison. The Labour Temple and other labour offices were broken into and ruthlessly searched by police for evidence of revolutionary plots. The Strike Committee condemned the arrests and demanded the release of the men, and the pro-strike veterans organized public meetings in protest. The state actors involved disagreed on how to proceed: Meighen, while recognizing the dubious legality of the arrests, wished to deport the prisoners; Robertson felt that deportation of the British-born radicals would be deeply unpopular. Members of the Citizens’ Committee pushed for leniency and a fair trial. Ultimately, six of the radicals were released on bail on the condition that they play no further role in the conduct of the strike. The left wing of the strike movement had won its (at least temporary) freedom, but the damage was done. The strike was left under the sway of the moderates.

In this environment of uncertainty, some strikers began to return to work. The streetcars resumed operation on June 18. This was perceived by many in the city as a sign that the strikers were losing the battle. The pro-strike veterans were incensed, and there was talk of violent retaliation even as the Strike Committee attempted to find a compromise with the bourgeoisie.

The veterans insisted that streetcar service be ended and that the capitalists settle an agreement with the strikers, or they would hold a public march on Saturday, June 21. Mayor Gray was openly opposed to such a march, fearful that it would break the tense peace and lead to all-out conflict. He was unable to prevent it, however, and so he called in the Royal North-West Mounted Police to maintain order.

The demonstrating workers and veterans pulled a streetcar off its wire and set it ablaze. The Mounties rode through the demonstration threateningly and were met by jeers, then by bricks and bottles. One rider fell off his horse, and a demonstrator began beating him. The other Mounties decided to fire into the crowd. The firing continued for several minutes; one man was killed instantly, and many others wounded. The crowd scattered and was met by the special police armed with clubs and revolvers. Mayor Gray asked General Ketchen to activate the militia, which had been significantly built up over the course of the strike, and militiamen armed with machine guns moved into downtown. This day would go down in Canadian labour history as Bloody Saturday.

The streets remained occupied by the special police, Mounties, and militia for several days thereafter. Individual strikers began to return to work, and further public meetings were prohibited. The Strike Committee agreed to end the strike if the provincial government would appoint a royal commission to study labour conditions and the cause of the strike. Premier Norris assented to this condition, over the objections of the Citizens’ Committee. On Thursday morning, the vast majority of Winnipeg’s workforce returned to their jobs. Although a few small sections of labour continued the strike, the working class had been totally defeated.[30]

It is clear that the revolutionary left failed this test of its power entirely. The working class had no civic institutions of its own which could substitute the functions of the bourgeois state, and thus provide an alternative to it. Although the Strike Committee made decisions about what labour was to be performed, it was thoroughly unprepared for this task, thus its collaboration with the city council. The strikers had not prepared for a takeover of society. A revolutionary program would have provided them with a road map for how to conquer state power and take ownership of the means of production; instead, the bourgeoisie won battle after battle for control of production and distribution.

While it is not the goal of this essay to prove that the Canadian labour revolt was or was not a revolutionary situation passed by, it is necessary to reflect on how socialists in the past have succeeded or failed to advance their revolutionary political project, so that the communists of today can better formulate their own strategy. Even if Canada’s working class could not possibly have been prepared to take state power in 1919, the events of that year were pivotal in the reformation of the revolutionary left, and with the right direction could perhaps have resulted in the formation of a mass, militant revolutionary movement. Instead, the revolutionary left remained minoritarian and ultimately failed to win the leadership of the workers’ movement or present the working class with a strategy for taking power.

General strikes and the formation of workers’ councils are not necessarily signs that the working class is conscious of its historic role and making a bid for state power. When the Russian workers and peasants formed soviets during the February Revolution, they were not yet prepared to govern society. It was the Bolshevik party and its program that put forward the slogan, “All power to the Soviets!”, and that led the workers and peasants to take power through the substitution of bourgeois political institutions with their own. Similarly, the Winnipeg workers did not ever seek to replace bourgeois institutions with their own. There was no party agitating for them to do so; no party pointing out that they were already administering the essential means of production to meet the needs of the people; no party agitating for the formation of workers’ militias so that the working class could defend itself against the bourgeois state and expropriate the capitalists.

It is the purpose of the revolutionary workers’ party to organize the working class for such an eventuality. The workers’ party, through presenting the class with democratic alternatives to bourgeois civil society even before the revolution, can prepare the workers for exercising state power. The party must become a state within and without the bourgeois state, by forming its own civic institutions such as schools and recreational clubs. Workers’ militias must be organized and trained by the party to defend the working class from the bourgeois state, and ultimately go on the offensive and seize control of the means of production when the opportunity arises. The party must train the proletariat to govern itself so that it can conquer and effectively wield state power.

The party’s program provides a road map to socialism. Without training the proletariat in self-governance, without preparing it for the conquest of state power, and without a political program that leads, in no uncertain terms, to a rupture with the bourgeois state and the institution of the workers’ republic, the working class cannot become a real fighting force, capable of contesting bourgeois hegemony. As the example of the Winnipeg General Strike demonstrates, the working class cannot struggle in an organized fashion for socialism without such a party. Relying on spontaneous revolts of the working class will result only in disappointment and defeat. The struggle for socialism is the result of a merger between socialist theory and the workers’ movement. This merger is embodied in the mass communist party, which is uniquely capable of organizing the proletariat to take state power and abolish the capitalist system of exploitation. Revolutionary unions and workers’ councils cannot substitute this essential instrument of class struggle; neither can a minoritarian party, limited to interventions in existing struggles. This lesson is essential if we are to avoid defeat, conquer power and bring about communism.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Ross Alfred Johnson, “No Compromise — No Political Trading: The Marxian Socialist Tradition in British Columbia” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 1975), vi. ↩

- Ian Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks: The Early Years of the Communist Party of Canada (Montreal: Vanguard Publications, 1981), 4. ↩

- Ibid., 5-6. ↩

- Ibid., 4. ↩

- Johnson, “No Compromise — No Political Trading,” 4. ↩

- Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 11-16 ↩

- Ibid., 21-22. ↩

- Gregory S. Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,” Labour/Le Travail, 13 (Spring 1984), 11-15. ↩

- Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 46-48. ↩

- For a discussion on why this was so in the West and not in the East, see Johnson, “No Compromise — No Political Trading,” and David Jay Bercuson, Fools and Wise Men: The Rise and Fall of the One Big Union (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1978), 1-28. ↩

- Ibid., 51-53. ↩

- This myth has been perpetrated by both right-wing and Communist Party historians, as well as later historians mistakenly repeating these claims. ↩

- Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,” 37. See also Gerald Friesen, “‘Yours in Revolt’: The Socialist Party of Canada and the Western Canadian Labour Movement,” Labour/Le Travail, 1 (1976), 139-140, and Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 53. ↩

- Friesen, “‘Yours in Revolt’,” 146. ↩

- Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 53. ↩

- Peter Campbell, Canadian Marxists and the Search for a Third Way (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999), 25. ↩

- Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,” 16-21. ↩

- Campbell, Canadian Marxists and the Search for a Third Way, 24-25. ↩

- Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour revolt,” 17-19. ↩

- David Jay Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg: Labour, Industrial Relations, and the General Strike, rev. ed. (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 114-117. ↩

- Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 55. ↩

- Ibid., 54. ↩

- Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg, 121-122. ↩

- Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg, 125-127. See also Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks, 29-32. ↩

- Ibid., 118-119. ↩

- Ibid., 127-131. ↩

- Winnipeg Citizen, May 21, 1919, 3, quoted in Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg, 130. ↩

- Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg, 132-135. ↩

- Ibid., 136-137. ↩

- Ibid., 150-175. ↩