Boris Souvarine was one of the leading founders of the French Communist Party (PCF) in 1921, after having founded the weekly Bulletin communiste, a publication dedicated to promoting adherence to the Communist International, in 1920. Bulletin communiste became an organ of the PCF, but ceased publication in late 1924, after Souvarine was expelled from the party for his support of Trotsky (with whom he would later break) in the Soviet factional struggles. This was part of a process called “Bolshevisation,” in which the Comintern’s member parties were brought into line with the commands of the centre (sometimes for the better, often as an expression of Soviet factional struggles). In the piece we present today, Souvarine fervently denies that this process has anything to do with the “true Bolshevism” of Lenin; in fact, he asserts that it marks a return to the “degenerated socialism” of the Second International.

The piece below was published in October 1925, in the first issue of the new Bulletin communiste refounded by Souvarine following his expulsion. In this article, he discusses not only Bolshevization, but also the French syndicalists, especially Alfred Rosmer and Pierre Monatte. Both of these revolutionaries became committed militants of the Communist Party (Rosmer in 1921, Monatte in 1923), only to be expelled alongside Souvarine in late 1924. Below, Souvarine both defends the place of these “communist syndicalists” in the PCF (while excoriating the “neo-Leninists of 1924”), and critiques them and their publication, Révolution prolétarienne, for once again taking up the syndicalist name.

At the heart of this piece is ultimately a commitment to organizing communists across theoretical lines. What matters for Souvarine is not theoretical shibboleths, but a commitment to class warfare, to the principle of communists’ active support of workers’ everyday struggles, to the dictatorship of the proletariat—in a word, to revolutionary Marxism. Serving the working class is communists’ highest duty for Souvarine, and this requires not only supporting the struggles of the exploited masses but also uniting the forces of those revolutionaries who have a common aim and method, the aim and method of revolutionary Marxism. This was what Souvarine fought for when he agitated within the Socialist Party (SFIO) for acceptance of the Comintern’s principles; this was what he fought for after his expulsion from the party he helped to build, insisting that the former syndicalists should not abandon the banner of communism, and that “when the Party really works for the proletariat, we should be with it.” It is only when the forces of revolutionary Marxism are united in the class struggle, in the service of the exploited and oppressed, that revolutionaries can truly advance the communist project.

Although Souvarine would ultimately grow farther and farther away from the communist movement, we present this piece on its own merits, as a defense of Marxist unity, and as a critique of both Stalinism and syndicalism.

Expelled, but Communist

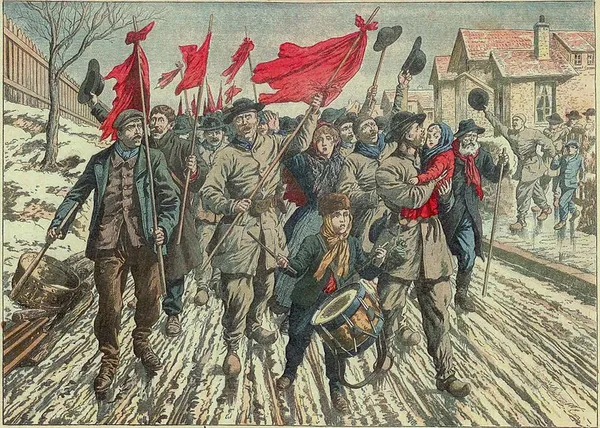

Translated from “Exclus, mais communistes,” Bulletin communiste 6, no. 1 (October 23, 1925).There was but a handful of men in 1914 who stood against the unleashing of bourgeois and proletarian chauvinism, the abdication of the International, the bankruptcy of socialism, syndicalism, and anarchism, the collapse of international solidarity between workers.

There was but a handful of revolutionaries in 1917 who supported the Bolsheviks, reviled and hunted; who expressed an active sympathy with them before their victory, and remained loyal to it in the bleakest of hours.

There are today, amid the crisis of international communism, but a handful of indomitable men who maintain the vital spirit of Marxist critique, who continue the living tradition of communism, who maintain proletarian consciousness in their class pride—against the deviations of the revolutionary organisation, against the abandonment of the proletariat’s general interest to the bureaucratic coteries, against the mortal dangers of adventurism, servility, and corruption.

The task is thankless and grueling. The architects of this curative resistance are drowned in contempt. The working class, misled once again, no longer recognise their own. But the men of the proletariat and the revolution have been through worse. They hold out. The certainty of the duty fulfilled animates them, their faith in immutably serving the same cause and being armed with tested communist truths fortifies them. If they needed, in 1914 and 1917, to “hope to engage,” they have been able to dispense with “succeeding to persevere.” Even more so, in 1924, they made their choice without regret, rich with the enlightening experience of the past ten years, which assured that their initial meager band was destined to become legion.

The outcome of the endeavor called “Bolshevization,” in accordance with the so-called “Leninism” invented after the death of Lenin, is not in the slightest doubt: it will be—it already is—a disaster. Russian Bolshevism, undefeated by the assaults of the capitalist world, diminished only by its recent internecine struggles, in time put aside the most novice exaggerations of the methods instituted after Lenin’s death. As for European neo-Bolshevism, the monstrous caricature of true Bolshevism, this has already gone bankrupt a year after its appearance, and it would disappear from the contemporary schools—if we can even call a set of sad practices a “school”—if it were not artificially supported by the Soviet Revolution, the strength of which is not the least bit revealed by the number of its parasites.

And the outcome of the work undertaken by the menders of the diverted communist movement is not anymore in doubt. But our efforts will be met with success only by a single condition: to remain loyal to the proven approaches that led to the strength of contemporary communism. The assimilation of knowledge and experiences acquired over the course of the last ten years of wars and revolutions is indispensable to the progression of the communist idea. The original traditions of the proletariat of each country are incorporated into this. But a return to old concepts, displaced by the active science of revolution, would be a veritable regression, no matter how revolutionary these concepts may have been in their time. We raise the question of whether the organ of our companions in the struggle for the restitution of the errant revolutionary movement, Révolution prolétarienne, by sporting the label of “communist syndicalist” (syndicaliste communiste), is taking a step forward or a step back.

(Revolutionary) syndicalism borrowed the elements of its school in part from Marxism, in part from Bakuninism, and in part from the mixed heritage of utopianism, reformism, and heroic insurrectionism, transmitted from generation to generation among the proletariat of the Latin countries. Even though the unevenness of its formation damned it to rapid extinction, it was able to represent a stage of communist thought superior to the degenerated socialism of the Second International: not only because the latter, in its decline, conferred an easy prestige on the former, but essentially because its practice was worth far more than its theory. This is why the Bolsheviks, before even having founded the Third International, considered the syndicalists to be allies, as a variety of communists destined to merge sooner or later into the organizations of communism.

Even more: the Bolsheviks knew to treat anarchists, strictly speaking, as combatants of the proletarian revolution, as auxiliaries, as possible reinforcements. Lenin wrote State and Revolution both to re-establish the Marxist conception of the abolition of the state, and to demonstrate that communists were differentiated from anarchists, on this point, by their means, and not by their goals.

In light of the plain failure of international socialism during the imperialist war, the rebirth of the proletarian International was accomplished with the aid of syndicalists and anarchists. Zimmerwald and Kienthal were our common will. Lenin was the one who directed this policy. Those excluded from the Congress of London in 1896 re-entered the International, under the aegis of left social democrats, radical Marxists, and Bolsheviks.

The first French section of the Communist International, called the Committee of the 3rd International (Comité de la IIIe Internationale), was formed from three subsections: left socialists, syndicalists, and anarchists. It was consecrated as the French branch of the new International. If anarchists and syndicalists split with us, it was of their own free will, not of ours. Repeatedly, even Zinoviev felt the need to address greetings to Péricat, which, in his fashion, he overemphasized….

The founding conference of the Communist International, in March 1919, declared in its “Platform”:

“It is vital to form a bloc with elements of the revolutionary workers’ movement who, in spite of the fact that they did not earlier belong to the socialist party, have essentially declared for the proletarian dictatorship through the soviets, that is to say, with syndicalist elements.”

In January 1920, the Communist International addressed a message to the revolutionary syndicalists and anarchists of the Untied States, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW):

“Our goal is the same as yours: a community without a state, without a government, without classes, in which the workers will administer production and distribution in the interest of all.“We invite you, revolutionaries, to rally to the Communist International, born at the dawn of the global social revolution. We invite you to take the place that is yours by right of your courage and revolutionary experience, at the forefront of the proletarian red army battling under the banner of communism.”

On the French syndicalists in particular, here is how Zinoviev spoke in 1922, at the 3rd World Congress, when Lenin was still there to give him instructions:

“The most important political observation made by the Executive and its representatives, of which several, such as Humbert-Droz, have spent nearly six months in France, is that—and we must speak frankly—we must search for a large number of communist elements in the ranks of the syndicalists, the best syndicalists, that is to say the communist syndicalists. It is strange, but it is thus.”

The same Zinoviev, in the same year, at the 2nd Congress of the Red International of Labour Unions, adopted this language:

“As we all know, the Second International was stricken by ostracism, and excluded from its organization whoever was more or less anarchist. The leaders of the Second International wanted nothing to do with these elements. They held the same attitude with regard to the syndicalists. The Third International has broken with this tradition. Born in the tempest of the world war, it has realized that we must have an entirely different attitude towards the syndicalists and anarchists.”

And Zinoviev referred to the first congress of the new International:

“At the First Congress of the CI, we said, ‘No one is asking the question: Do you call yourself an anarchist or a syndicalist? We ask you: Are you a partisan or an adversary of the imperialist war, for a relentless class struggle or no, for or against the bourgeoisie? If you are for the struggle against our class enemy, you are one of us…’”

This is not all. Zinoviev said further:

“We estimate that all the anarchists and all the syndicalists who are the sincere partisans of class struggle are our brothers.”

And finally, so as to quash any sort of ambiguity:

“The anarchists have organised a whole range of attacks against us. However, we do not intend to revisit our attitude in regard to the anarchists and syndicalists. We maintain our positions. As Marxists, we will be patient until the very process of class struggle brings into our ranks proletarian elements who still remain outside of our organisation.”

It would be superfluous to quote any more to determine the traditional policy of the Communist International towards communist syndicalists.

This policy has borne its fruits. The Communist International has recruited among the syndicalist ranks—perhaps anarchist syndicalists, more likely communist syndicalists—the elements that we have always considered “the best,” and without which certain sections of the Communist International would not exist.

In America, it was among the syndicalists (William Foster, Andreychin, Bill Haywood, Crosby), among the left socialists around The Liberator sympathetic to the IWW (John Reed, Max Eastman), among the anarchists (Robert Minor, Bill Chatov), that it found most of its communists.

In England and Ireland, it was among the syndicalists (Tom Mann, Jim Larkin, Jack Tanner) and in the movement of the Shop Stewards’ Committees, of a syndicalist nature (Murphy, Tom Bell, etc.), that it recruited.

In Spain, it was among the syndicalists and the anarchists that it found Joaquim Maurín, Arlandis, Andrés Nin, Casanellas, and many others.

In France, finally, the Communist International drew from the syndicalist ranks those who, alongside the new militants who emerged from the war, should, according to the CI, exercise decisive influence, and gradually eliminate that of the social democrats inherited from the old party, of obsolete Jaurèsism and null Guesdism. It was by Lenin’s uncontested authority that Rosmer became the primary French representative to the Executive. It was Zinoviev, Lozovsky, and Manuilsky who accorded the highest priority to bringing Monatte into the Party. Certainly, Trotsky was not the last to support this policy, but never did he give up on winning the communist syndicalists to the purely Marxist conception of communism, and his last discussion with Louzon remains memorable.

Even today, when the French Communist Party is diminished, emptied, weakened, after a year of pseudo-Leninist dominion, it is the syndicalists of yesterday, the anarchists of the day before yesterday, like Monmousseau and Dudilleux, that the Executive is forced to go find.

How, then, can we explain the 1924 neo-Leninists’ spontaneous and systematic defamation of this “communist syndicalist” journal, even though all the Communist International’s platforms, resolutions, commentaries, traditions, recruitment practices, command them to treat its founders as friends, as allies, as communists, and even as “brothers,” as Zinoviev has said?

The answer becomes clear with irresistible logic and force, disengaged from the official communist texts quoted above: these false “Leninists” act as the most vulgar social democrats. They have naturally adopted the attitude of the Second International—condemned by the Third, to which they are profoundly foreign, or into which they have intruded. These people know nothing of our movement, of our ideas, of our history. Placed in the presence of an unexpected question, to which the solution was not prepared for them by the bureaucracy allocated to this task, and to which their inaptitude for work prevented them from finding enlightenment in the documents available to all, they improvised an answer, and, as is their habit, pronounced a great deal.

Their specifically social-democratic reaction to “communist syndicalism” characterizes an entire doctrine.

“How can one be Persian?” Montesquieu jested agreeably. “How can one be a communist syndicalist?” ask the creators of 1924’s “Leninism.” The Communist International, in the time of Lenin and Trotsky, responded in advance. It was only after the death of the first and the absence of the second that in this question, as in so many others, true Bolshevism was thrown out, and replaced by the offensive return of degenerated socialism, masked in neo-Leninism.

But if Révolution prolétarienne is far above the commentaries of its detractors, it is within range of the critique of its friends, of those who, in agreement with Zinoviev on this question, consider communist syndicalists to be “brothers.” And we must clearly say that many of us do not approve of the label.

What is our rationale? Ten issues of the journal have appeared and we have found nothing that justifies the abandonment of that which we call simply “communism.” Monatte and Rosmer said after their expulsion: “We return to whence we came.” This is meaningless. Why not remain that which they had become—“communists”? We understand that they still are communists. But this should suffice. Unless the experience has led them to introduce something new into their theories? They have surely not abandoned the old without mature reflection.

Monatte, Rosmer, and Delagarde were expelled from the Party by way of senseless accusations—with the secret aim of pushing them down a hill that they could not reclimb. This wish was immediately dashed, and none of those who knew them expected anything else: only foreigners to the communist workers’ movement could hope to eliminate them. They remained themselves, but they changed their name. As if they wanted only to differentiate themselves from the demagogues who discredit the communist name. But the name of syndicalist is no more pristine than that of communist; the marks are less recent, is all.

They remain loyal to the Marxist conception of class struggle, the proletarian dictatorship, the state. And as for Lenin’s conception of the Party and the International? They said to our comrades, after their own expulsion, “Remain in the Party, you are in your proper place.” And they discussed the day when the party would become truly communist, when the mass of communists outside of the party would retake it, themselves among them. None of this has anything to do with syndicalism.

All that remains is that they are profoundly disappointed with the degeneration of this Party that together we attempted to make communist, and that they do not wish to renew their attempt, preferring instead that others do so. An understandable feeling, but a feeling only, and totally personal. They can even less theorize it than they can say simply, “Comrades, remain in the Party.”

In fact, when it comes to true syndicalism, we found nothing other than an article by Allot. And this syndicalism is nothing new; it is old, and it is not of the best of its kind. Allot’s article, so remarkable on a number of fronts, serious, documented, and instructive, ended on an elementary critique of the intervention of the Party in a strike. But what does Allot demonstrate? Exactly the opposite of his intention. He proved that the Party did well to intervene in the strike in question. Whose fault is it if “the trade union organizations appeared to be erased”? If the facts establish that syndicalism does not suffice at all? It is a critique that well represents the impotence of syndicalist theory, as this justifies the criticized acts. Since when have strikes had for their goal to save the trade unions from their “erasure”? Is the strike conducted for the union, or is the union made for the strike? The strike has as its goal the satisfaction of demands: if the goal is achieved, all that has contributed is good. If the Party plays a part, all the better for the workers first, for the Party after. Nothing is more legitimate than the benefit gained by the party from serving the working class. What is condemnable is an attempt to profit from a situation to the detriment of the working class; but nothing like this took place at Douarnenez. “Communists,” said Marx and Engels, “have no interests distinct from those of the proletariat in general.” This undying principle remains our law: the communist party that lives up to it acts well, that which discards it loses its communist quality.

The Party that has lost its political sense, its consciousness of its role, intervenes by disserving the movement that it pretends to support. The clumsiness, incapacity or indignity of those responsible cannot be placed on the principle of interference. It is possible that at Douarnenez, certain communists said foolish things, but none of them had a monopoly, and this does not prove that the Party should not involve itself in workers’ struggles. Critiquing the mistakes made, without having the special goal of emphasizing the union or the Party, simply in pursuing the interest of the strike, this is serving the working class and, at the same time, without doing so expressly, the union and the Party themselves. Because the union and the Party have no other well-understood interest than that of the proletariat.

That which discredits our Party and our International is a tendency to ignore the interest of the working class to serve the interests of the bureaucrats. But when the Party really works for the proletariat, we should be with it. This is made all the easier for us by the fact that it was us, including Monatte and Rosmer, who worked so hard to substantiate this idea that the Party must occupy itself a little less with vulgar politics and much more with workers’ struggles. If the communist deputies loitered less in the halls of the Chamber and frequented more the meetings of strikers, all the better.

The remnants of old doctrinaire syndicalism, the attempt to revive ideas that have no more historic value, are not progress from the step already traversed by the syndicalists who became communists. And they add to the already large confusion that troubles the consciousness of the working-class vanguard. The less of this we find in Révolution prolétarienne, the more it will strengthen itself in its task of revolutionary restitution.

The question of a return to syndicalism could perhaps have been posed if the communism of 1919-1923, true communism, that of the first four congresses of the Third International, that of Lenin and Trotsky, had failed. Such a catastrophe would have put into question all its theories, all its practices. But happily, nothing of the sort came to pass. That which failed was not communism, but its caricature, the “Leninism of 1924.” That which failed was not Bolshevism, but its parody, so-called “Bolshevization.”

The communism of Marx and Engels, Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky, is sufficient to guide militants to working-class emancipation. The last word has not been said. More will come who add onto the greatest teachings of the communists. But the spirit of communism will be immutable, and we will inspire ourselves to serve our cause with dignity.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.