Up close, DSA Bread and Roses (the “centralizers”), DSA Build (the “decentralizers”), and Marxist Center look pretty different. What do a unified social-democratic faction, a loose opposition alliance, and an aspiring cadre party have in common?

Step a few feet back, though, and their distinctions lose significance, like the different-colored dots of an Impressionist painting blending into a coherent whole.

Class is everything. A libertarian professor of economics and a radical professor of women's studies may hate each other, but they both make five times as much as the janitor who cleans up after them - and more importantly, they spend their lives in the same educated, affluent milieu.

Despite its egalitarian pretensions, the US political system is run by the middle class for the benefit of the ruling class. There is effectively no political culture outside of those classes (a very few isolated and localized examples notwithstanding). As Bernie Sanders said, poor people don’t vote, let alone protest or form political organizations. Of course, the dispossessed do resist their dispossession, all the time - but they do so outside of the political system (and usually, in limited and decentralized ways, everyday oppression and everyday resistance tending towards a socially-stable equilibrium).

US socialism is a fringe of the official political culture. Its class makeup reflects that. It is college-educated, affluent (or at least with affluent parents), and attuned to the concerns of middle-class professionals and students in general. Whether they’re door-knocking for Bernie, waving anti-imperialist placards for the cameras, or running brake-light clinics, it's the same people from the same backgrounds mobilizing each other.

In other words - should they arrange themselves into a centralized electoral front, a federation of autonomous activist hubs, or an ideologically united party? Shouldn’t they first prove why they, as a subculture, matter in the first place? Normcore social democrats and social-reproduction-theory feminists both claim to represent the authentic working class. If that's true, why do both sides seem to be made up mostly of journalists and humanities postdocs?

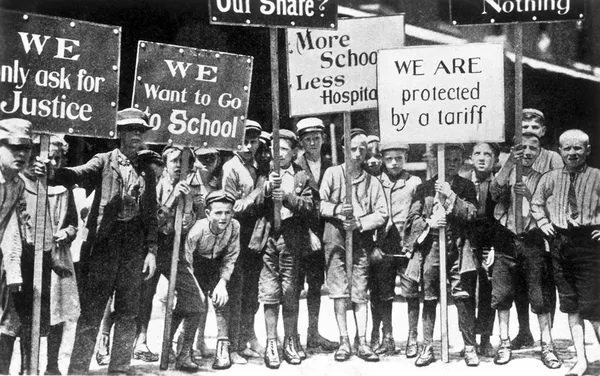

Where are the call-center workers? Where are the home health aides? Where are the McDonald’s fry cooks? Everyone talks about them, but when was the last time you saw one running an activist meeting? How many of the working poor have you ever seen at a leftist event - other than the venue staff?

Traditionally, Marxism draws a line between intellectuals (professionals, technicians, and all those whose specialized training and knowledge gives them a uniquely strong position in the labor market) and the proletariat (the truly dispossessed, the mass of workers and unemployed whose “unskilled” status makes their labor more-or-less interchangeable from capital’s point of view). The latter, not the former, carries the revolutionary seed, both because it owns no means of production (not even professional licenses and training!) and thus has no stake in preserving class distinctions and because the logistically-socialized, large-scale economy it operates makes it possible to raise everyone’s standard of living. Now, intellectuals can contribute to the great work of organizing the proletariat for power, but only by immersing themselves in its life. They must make their struggles their own.

These days, US leftism has lost that awareness. To hear any faction of DSA (or Marxist Center) talk, K12 teachers, college professors, and even professional athletes are proletarians. Instead of dedicating their lives to serving the masses, intellectual-class radicals would rather band together with each other and creatively redefine the proletariat to include themselves. But while they may fool each other, they can’t fool the larger social process of class struggle. In terms of their historical and economic context, all their factions are variations on the same theme as MoveOn, the National Organization for Women, and for that matter, Young Americans for Liberty. They’re all ideologically-defined middle-class protest movements.

Now, as an individual, there's nothing morally wrong with being an intellectual. That’s my class background, and if you’re reading this there’s a better-than-even chance it’s yours too. Intellectuals can contribute plenty - they have administrative, research, fundraising, and bookkeeping skills (from higher education), extra time and energy (from middle-class jobs), and better physical health in general (from better healthcare access). If intellectuals go to the proletariat, immerse themselves in it, dedicate their lives to it, and help organize struggle committees in low-wage workplaces and slumlord-owned buildings, they can be a truly valuable part of the class struggle. And historically, red unions and communist parties have always attracted their fair share of radical-minded intellectuals. Many of them have brought social-scientific and historical knowledge that’s helped break the stability of the oppression-resistance equilibrium, opening up new space for class struggle.

However, the US’s actually-existing socialist groups are there for their own sake, not as supporting organizers for struggle committees. Their understanding of “mass” as “anyone who shows up to protests” (and “vanguard” as “anyone who agrees with this list of ideas”) help keep their concerns and membership middle-class and insular. So does their commitment to the US’s political process - and even the ones with the most revolutionary posturing are still committed to participating in that process, albeit via protest rather than lobbying. It comes out the same either way.

Revolution does not mean “sweeping social change” in some abstract sense. Sure, it involves deep and systemic changes, but those are an after-effect, not the thing itself. Revolution means overthrowing the government. It’s literal. Similarly, socialism doesn’t mean “Liz Warren’s policies but more so” (and flawed as my four-tendencies typology was, I stand by “government socialists” for those whose “socialism” means taking progressive Democrat ideas and extending them just a few degrees further than John Oliver). Socialism means the proletariat (not the liberal-democratic state) owns the economy and runs it according to a central plan, not an ad-hoc collection of welfare programs and “socially-conscious” nonprofits. Creating that will take a full-blown revolution, not a gradual build-up of legislative reforms, because the liberal-democratic political process will never allow socialism. It never has and it never will because it was designed from the get-go to make that impossible. It does that not by banning dissent but by giving it a venue to express itself and lobby the government (or protest it!), thereby taming it into a perpetual loyal opposition.

That’s why any socialism that’s bound to the political process is self-defeating in the end. However, class is thicker than ideology, so any movement based in the middle classes will always bend back towards the political process.

Inasmuch as it’s more than a buzzword, base-building contains a kernel of the right idea. Socialist intellectuals can engage with proletarian tenants and workers in a mutually-transformative process, accumulating experience one struggle committee at a time. That process can eventually rekindle the mass socialism that the US hasn’t had for generations. However, the thrust of that organizing must always be away from and against collaboration with the government. That means not lobbying it, participating in its elections, taking its money, or - and this is what almost no activist figures out - protesting it. Part of the normal function of a liberal-democratic government is to be periodically protested; why else do you think it’s in the Bill of Rights? Liberal states are stable in part because they work like lightning rods, attracting dissident anger and channeling it harmlessly into the ground.

Instead, the way forward is to steadily and patiently gain experience with class struggle, gradually cultivate a base among the dispossessed, and eventually begin to develop the necessary forces to establish revolutionary sovereignty: not joining the official political realm but creating an entirely new one, an insurrectionary proletarian state (“dual power” the way Lenin meant it).

I spent years in the middle-class, activist Left, including as an early Marxist Center organizer. I don’t write this to set myself up as embodying some kind of virtue that others lack; everything I’m critiquing here, I was doing myself two years ago. When I call it a dead end, I’m not talking from ignorance.

But I left. I changed the type of organizing I’m involved in and, more importantly, the constituency towards which I orient. I invite you to do the same. Would you rather spend the next ten years rehashing the same debates as the last ten with the same people from the same class background (voting or consensus? Smashing windows or holding banners? Democrat or Green?), while history continues to leave you behind?

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.