Nick Walter, labor organizer, IWW member, and writer at Organizing.Work recently published an article titled “Labor Law Doesn’t Advance Class Struggle, The End.” As the pithy title indicates, the argument is that labor law isn’t the answer for developing and pushing forward the class struggle. Walter’s solution? Direct action.

But Walter’s piece suffers from a simple error - a reification. To reify is to mistake an abstract category for something concrete. In Walter’s case, he mistakes the particular or concrete labor laws which he dislikes for the abstract category “labor law” as a whole. This mistake is a function of ideology. Walter’s outlook is straightforwardly in line with that of Organizing.Work (OW from now on) more broadly, which is a kind of mass strike anarchism. This outlook views the law, and thus politics and the state, in a reified way - as nothing more than a distraction from direct action militancy. Unfortunately, this position is ahistorical and ends up contradicting itself in practice. As a result, either the theory or the practice must change.

The error is simple: If I claim all sandwiches are bad because they have mayonnaise, I’ll be hard-pressed to justify any future obsession with paninis. Even if I drag out the point that the paninis I eat don’t have mayonnaise, I’ve contradicted my initial claim: how can paninis be good if all sandwiches are bad? This silly illustration highlights the logical problem of Walter’s position. What he’s really after is better labor law, not the abolition of labor law. He even says as much:

“I was arguing for concerted activity protections like exist in the United States and the people from a few of the unions were uneasy about that.”

This is also the clearest sign that not all labor law is the same. Walter likes Section 7 of the Wagner Act. This section protects the right of workers - union or not - to engage in certain protected, concerted activity while at work. But then is this too a mere snare? How does this hold back militancy? If anything, it appears to protect it. So does all labor law hold back militancy or not? Walter’s position reveals itself to be a contradictory one.

I suspect that such a frank contradiction of the essay’s central argument is a result of Walter’s practical focus. He’s less concerned with abstract consistency than with what works in practice. That’s not a completely unreasonable position to have as a labor organizer, but unfortunately that approach will lead to contradictions in practice. In order to describe the contradictions that Walter’s pragmatic unionism runs into with the law, it will help to establish the outlook of OW more clearly.

OW is a blog edited by organizers in the IWW. It is not an official publication of the union, but is instead an effort by organizers to share stories about organizing and discuss strategy. OW's outlook is basically that of the anarcho-syndicalists and left-wing of the Second International, which dedicated its efforts to organizing for mass strikes:

“Many of us – the contributors and editor – are members of the Industrial Workers of the World. As a model, we favor “solidarity unionism”: a committee of workers in the workplace democratically running the union effort, and taking direct action “on the shop floor” to get what they want.”

This is to be expected, as the IWW was firmly in this camp from its founding throughout its peak.

The outline of the mass strike strategy is that any sort of revolutionary movement of workers for a new society requires the development of the working class’s ability to carry out mass, militant direct actions to force their demands. This much united the Left-Wing and Center of the Second International.[1] Where the Left goes one step further than the center is its claim that direct action and direct action alone is the class struggle, and everything else a mere reaction to or distraction from this activity.

Walter and other authors at OW have argued that unions ought to exist primarily to develop this direct action capability. Where unions don’t develop direct action, they fail, no matter the bread and butter gains, changes in working dynamics, and power at work. In contrast, where unions develop militancy, they are winning, no matter their size, their reach, and barring only outright manifestations of backward political development (racism, misogyny, etc.). For example, Walter writes:

“CUPW won pay equity in the 1970s through massively disruptive strikes that were less than legal. The Employment Insurance we have in Canada is as much due to a riot in the 1930s in Regina, Saskatchewan than any other single factor. Class struggle is how we turn around the current state of things. We certainly don’t win every time. But if you count up all the wins over a long period you notice that you make a staggering amount of progress that way, far more than you would from all of the best legal minds and an infinite budget for arbitrations and board hearings.”

Here, Walter is equating mass direct action to class struggle. Indeed, this position has been put forward in multiple OW pieces.

In “Canvassing is not Organizing”, Ray Valentine argues that political organizing isn’t the same as union organizing. But this isn’t what the title says. The title argues that a tactic which even unions have used to success is somehow not organizing at all. The author’s real point is that “The techniques of political campaigns are designed for a particular purpose, and that purpose is not organizing the working class to wrest control of social institutions and emancipate itself.” This outlook appears to suggest that because capitalists use the “technique” of drafting organizational rules, any working-class movement must avoid drafting rules. After all, we’re told that because a capitalist might organize a political party and campaign for support, the very practice is therefore off-limits. This is absurd on its face. The state is the preeminent social institution in capitalism, and politics is a struggle between classes over which controls the state. Valentine’s claim that politics is not a struggle over which class controls social institutions falls on its face.

Walter’s own review of Jane McAlevy’s “No Shortcuts” argues that electoral politics are a snare for union members and leaders. Elections distract union members and leaders from the use of their “subversive” and most effective element - direct action:

“This subversion of the existing economic logic of society is why the right wing and business interests hate unions so much. But when unions break from this logic and enter conventional politics they find themselves drawn onto a terrain where they have no power. It allows union leaders (and high-profile union staff) to believe there is something other than economic disruption that gives them a bargaining chip. It’s not that union leaders can never have political influence inside the halls of power; it’s that the only influence they can have comes from laying down the source of their power.”

The essay at hand provides other evidence of this outlook. Walter is critical of card check, first contract arbitration, and imposing certification where the employer’s illegal anti-union conduct tainted the election process. Why? Because these laws: “exist[] to condition a certain kind of union into existence.” What kind of union? A union that dampens militancy rather than developing it. The unstated premise is that developing workers' capacity to carry out militant direct action should be the primary focus of unions.

I want to note that I agree with Walter’s criticisms of the limits to card check and first contract arbitration. They pose the danger of conferring the responsibility of being a union without having developed local leaders and organizing capacity. But what are we developing militancy and direct action capacities for? To change social relations. As noted above, the purpose of politics is to contest sovereign power. I’m using the concept of sovereign power here because I share anarchists’ reasonable skepticism of the capitalist state. But politics doesn’t have to be solely about winning control in the extant state. Politics can also be about reshaping that state, or even fighting for a new form of state, or sovereign power, altogether. Ultimately it is the form of state power that determines which class is sovereign. This need to contest the sovereign power in society - the need to engage in politics as such is connected to Walter’s aversion to legal issues: the law is, after all, what the state enforces.

In contrast to the Left, the Center of the Second International saw mass direct action as a necessary but insufficient component of class struggle.[2] One purpose of the political realm of the class struggle is to shape the legal terrain upon which direct action can take place. Viewed in this light, questions of law lose their mystification - no law vs. some law becomes a debate about what kinds of laws and why? Though the state form determines which class is sovereign, the nature of class sovereignty is such that it must permit some degree of freedom, even for members of the oppressed and exploited classes. This is a key feature in the distinction between slave societies and class societies - the exploited in a slave society aren’t juridical persons, but instead, property. In contrast, workers are, constitutionally speaking, afforded the same rights in the state as professionals, small business owners, landlords, bankers, and capitalists. However, in the regulation of private affairs, the state may reach out and accommodate landlords here, or tip the scale against workers there. Thus, the state’s structure - its working rules, the limitations it puts on the actions of workers on the one hand, and capitalists on the other - determines which class is sovereign in and through its regulation of ‘civil society’ or contracts, agreements, and disputes between supposedly ‘non-state’ individuals.

Here is where the contradictions come in for Walter. It is illusory to fight for a purely state-independent labor movement in the U.S. and it always has been. The first reason this is true is that it isn’t practical. The second reason is that there is no historical basis for doing so.

In theory, Walter wants to develop the independent power of the working class to take militant direct action to force demands. But in practice, almost every I.W.W. campaign touted on OW has availed itself of the National Labor Relations Board and filing Unfair Labor Practices (ULPs) in order to pressure employers to cave. When we file a ULP we’re asking a well-salaried government official to investigate the illegal conduct of the employer. We’re asking that they bring the weight of the government to bear on employers, that eventually this weight either leads to a decision and enforcement against the employer or, more likely, ends up pressuring the employer to settle.

This isn’t a marginal question if you argue that working-class power comes from direct action and self-organization alone. It’s a straightforward contradiction. According to this logic, if we really want to develop mass working-class militancy, then we need to eschew ULPs, the NLRB and everything related. We would also be expected to eschew even the rare federal injunctions by courts against employers and many other court-ordered judgments. But why? What business does a class struggle (read “direct action”) union have relying on the bourgeois state?

After all, any reliance on the state and its force against the bourgeoisie supposedly legitimates the state as an institution that executes law on behalf of workers. Even if it is merely a court injunction, it deludes the workers into thinking that they can expect the state to go to bat for them again in the future.

However, Walter and OW clearly do not advocate for a pure anti-state position. And the reason they don’t do this is the same reason Walter doesn’t actually believe all labor law holds back class struggle: it wouldn’t be practical. Indeed, beyond his praise for Section 7 rights, Walter admits to even minor benefits from contracts: “A union contract can represent a more favorable legal terrain for certain disputes but more often than not it’s also about writing down a series of trade-offs.” It is indisputable that all law is just words on paper or in the mouths of lawyers and judges without enforcement. But when we assume an anti-legal political posture, we cut off opportunities to utilize court-ordered enforcement of the law and any discussion and development of a strategy to do so. Walter’s position foments the type of disengagement that leads to less favorable enforcement of the law and as such, it is a retreat from a theater of class war.

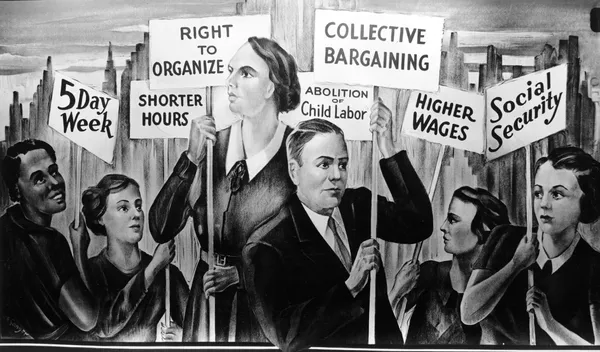

The second contradiction is that labor history provides us with legal reforms that have allowed or encouraged the development of class struggle. It is common for leftists, especially mass strikists and anarchists to point to the 1933-34 strike wave as a spontaneous or at least purely direct action affair. The strike wave was an explosion of working-class militancy and organizing which then led to the emergence of legal reforms that certified in law the rights won in practice. But this is a convenient fiction. The 1933-34 strikewave wasn’t spontaneous. The central flaw of this claim is that it assumes what it needs to explain. Why did workers decide to engage in strikes across the country in 1933?

It wasn’t just prior organizing. Yes, for years prior to the passage of the Norris LaGuardia Act, Socialists, Anarchists and Communists were involved in every type of organizing - boring from within and forming independent unions.[3] This organizing developed the radicals as militants within the labor movement, earned them respect, and set them up to take advantage of the economic crisis that would emerge at the turn of the decade. But most of their organizing attempts were rolled back and crushed. The historical reality is that it was a set of political-legal reforms that triggered the strike wave. The passage of the Norris-LaGuardia and the National Industrial Recovery Act was the 1-2 punch that opened up space for workers to lead the 1933-34 strike wave.

The first punch was the Norris LaGuardia Act, which restricted the power of federal courts to issue injunctions in labor disputes. For decades, U.S. courts had granted and enforced injunctions against striking workers. Anytime an employer was faced with mass direct action of workers, they would go to the courts and argue that this action violated the rights of the employer.[4] Senator George Norris and Representative Fiorello LaGuardia were two progressive Republican politicians that pushed their bill through Congress in 1932. The act laid out 9 things Federal courts could no longer enjoin, including striking, joining a union, supporting striking, and publicizing about an ongoing strike or labor dispute. This restraining of federal district and appellate courts helped tie up the hands of the judiciary for the 1933 strike wave.

The second punch was the National Industrial Recovery Act. Passed in 1933, the NIRA included this language:

“employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and shall be free from the interference restraint, or coercion of employers of labor, or their agents, in the designation of such representatives or in self-organization or in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection[.]”[5]

This is Section 7(a) of the National Industrial Recovery Act. It would go on to form the basis for the same Section 7 of the Wagner Act which Walter finds so appealing. This second blow pushed the capitalist class off-balance enough that millions of workers began streaming into unions - liberal, communist, anarchist - whichever, in the wider context of the depression. These two pieces of legislation opened up space for workers across the country to assume an offensive posture against employers. In other words, they advanced the class struggle.[6]

These contradictions suggest two things. First, it suggests that the position of OW and Walter is untenable because it is contradictory in practice. This in turn calls for the OW types to reconcile their outlook, either going for the deeply impractical position of being ‘purely anti-state’ or merely adjusting their ideology to reflect their practice - admit that the law can at times “advance” class struggle. That is, law can be useful for workers and unions to use because it can allow us to leverage power to limit some conduct of the employers. OW accepts this in practice but rejects it in theory.

Second, if it is true that the state can be leveraged to help worker organizing, then it suggests that class struggle is not exclusively limited to direct action by workers. Then we should develop a clearer theory of the law and a better strategy for using it in practice. We should ask what ways of using the legal arena comport with our principles.

I suspect this will be a hard pill to swallow. I have a great deal of respect for Walter and the writers and editors of OW, but by reducing the class struggle to direct action, they risk painting themselves into a corner. The argument goes like this: We need a revolution in our political system. Political change happens with class struggle. Class struggle is the mass direct action of the working class. Then, either true politics is limited to direct action or if politics is defined to go beyond direct action (voting in elections, running campaigns for legal reforms) then politics is merely a distraction from class struggle. The result is that as long as this outlook is hegemonic, we will continue to organize on legal terrain laid down by our class enemies, instead of winning reforms that shape the terrain in ways advantageous to the working class. If we don’t start thinking politically and legally, we’ll remain cornered in our defensive posture indefinitely - and labor’s last 50 years of body blow after body blow will continue, unabated.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Indeed, it united the IWW left-wingers like Big Bill Haywood with IWW and SPA Centrists like Eugene Debs. ↩

- See, for example, E. Debs: “Socialism must be organized, drilled, equipped and the place to begin is in the industries where the workers are employed. Their economic power has got to be developed through efficient organization, or their political power, even if it could be developed, would but react upon them, thwart their plans, blast their hopes, and all but destroy them.” “Danger Ahead” 1912. https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1911/0100-debs-dangerahead.pdf ↩

- Zeitlin and Steppan Norris, p. 33-39. ↩

- “Injunctions are orders issued by courts to prevent unlawful interference or threatened interference with the rights of the plaintiff, who relies on one or more of the following principles of equity—that the damage would be irreparable, that the remedy at law through criminal prosecution is inadequate, that the interference threatens to continue, or that a multiplicity of actions would be involved” https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre1950032500 ↩

- Section 7(a) of the NIRA. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=66&page=transcript ↩

- See also, Mike Davis Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the U.S. Working Class. Pp. 55-69. Davis rightly describes 1933-37 as the “highwater mark of the class struggle in modern American history[,]” and notes that it “start[ed] with the 1933 ‘NRA’ [National Recovery Administration, set up by the NIRA] strikes….” ↩