Suppose you’re waiting at the DMV. The wait, per usual, is dragging on and the queue is long. Suddenly somebody enters the facility without checking in and walks straight up to a window. The person assures the patiently waiting crowd that the DMV employee is his niece. He proceeds to have his vehicle-related business taken care of. For most Americans, this would be utterly intolerable. However in Eurasian culture, specifically in ex-Soviet countries, this is not only considered acceptable but is expected. If for instance, the DMV employee told her uncle to wait like everybody else, onlooking strangers would sneer at her with contempt: “That’s your family, how could you do that to them?”. All throughout Eurasian culture, we find these kinds of relations being employed by the ruling class to better maintain their domination over society.

From this observation, Political Scientist Henry Hale has constructed a theory of what is called patronal politics, or patronalism. This theory, as elucidated in the book Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective, has emerged as one of the most cogent frameworks within comparative political science to analyze the post-soviet world. Despite emerging within ‘bourgeois’ academia, Hale’s theory of patronalism presents Marxists with an opportunity to expand their knowledge of the institutional forms of bourgeois rule. This is not to say that Hale's theory is not without error, especially when examined from a Marxian framework. However, when the theoretical framework of patronalism is ‘marxified’, the systemic dynamics of Eurasian states (from Tsarism to Putin) become clearer. This can help us attain deeper insight into how the first great Communist experiment operated, and ultimately how it failed. Furthermore, the patronal system will help us understand Eurasian society as it is now, precisely for the purpose of overturning the patronal system.

Patronal politics is defined by Hale as “...politics in societies where individuals organize their political and economic pursuits primarily around the personalized exchange of concrete rewards and punishments through chains of actual acquaintance, and not primarily around abstract, impersonal principles such as ideological belief or categorizations…”[1] Anyone familiar with the nomenklatura of the ex-USSR, or with the nature of political corruption in Russia might find Hale’s formulation too obvious. However, when this system of patron-client relations is examined, deeper insights into the nature of the social relations of this region can be uncovered.

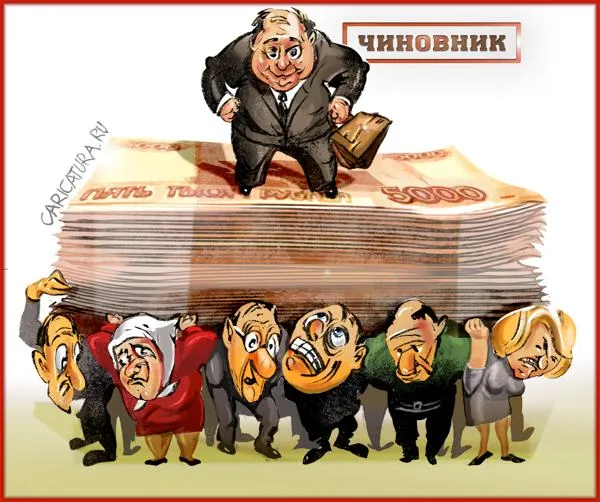

Hale explains how patronalism distributes power in given states through “roughly hierarchical networks through which resources are distributed and coercion applied.”[2] Hale demonstrates these patterns through exploring a multitude of social spheres where patron-client relationships dominate and mafia-like networks run the show from behind the scenes of a formal state sphere. State processes in this region cannot be analyzed through regular institutions and political parties. Rather, informal social networks make decisions in accordance with a specific structure that revolves around extended patronal pyramids. In the post-soviet space, actual power is acquired and utilized by means of favors carried out by clients for patrons. If, for instance, a business owner helps a patron in securing electoral victory, they will more than likely acquire themselves favorable contracts with the state. Think corrupt Chicago machine politics, but on a national scale.

A pyramid structure exists extending from the top (patron-in-chief, which is usually the literal head of state), down to sub-patrons (who are usually oligarchs, or directors of state institutions), down to lower levels of the political world, all the way down to the private and personal lives of citizens. This informal system is so extensive that the daily lives of working-class people are required to play the game, lest they be reprimanded by a highly corrupt business and legal sector. A Marxist version of this theory would recognize and explore the factors which gave rise to this unique form of social organization in this part of the world (likely exploring the period of hyper-capitalism in the 1990s, superstructural conditions, and so on) while stressing the need to explore the class dynamics in societies dominated by patronalism. For example, while Hale certainly looks at the development of oligarchies, a Marxist would center their analysis around the oligarchs as a ruling class that uses this informal system to maintain ideological and material power.

If it wasn’t already clear, this system is endemically informal. For Hale, the informality embeds corruption and forms the basis of a social equilibrium where, “Given that everyone expects everyone else to behave this way, it makes no sense for an individual to behave differently since she would only wind up hurting herself and possibly those who depend on her, possibly severely.”[3] When, for instance, somebody reports political corruption, or notifies the police when the mayor’s son commits an atrocious crime, they are not only punished immensely by the state-repressive apparatuses and legal system but are also seen as absolute morons by common people. As unusual as it may be to the western mind, many Eurasian citizens would be more likely offended if an officeholder did not use their political power to benefit his family. It is understood and accepted that the government is used for pilfering by officials, and officials who actually refuse to do so are ironically seen as idiots.

Before laying bare the genesis of modern patronal social relations, Hale describes how patronal patterns emerged in hunter-gatherer social formations. The Marxist framework refers to this formation as primitive communism, and would agree with Hale’s assessment insofar as Hale states the primacy of personal relationships within this prehistoric social formation. Most Marxists, however, would likely consider Hale’s statement that “Patronalism is in fact the norm throughout all recorded human history…”[4] as utterly ahistorical. Henry Hale describes patronalism as a sort of default mode for social organization, which traps humans into a social equilibrium which is less optimal than a formal arrangement. This thesis seems more to be a product of liberal bourgeois ideology than of historical exposition. Furthermore, while personalized networks were absolute in primitive communism and even important in almost every social formation, this is not what patronalism is. patronalism is by definition rigidly hierarchical, while by Marx’s definition primitive communism is relatively egalitarian. Furthermore, for the Marxist, humans are not by nature patronalistic. They create patronal circumstances as conditioned by a specific historic juncture where the mode of production plays a primary role. As Frederick Engels put in the preface Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State, “According to the materialistic conception, the determining factor in history is, in the final instance, the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life.”[5] Instead, however, of getting caught in the quagmire of anthropological discourse on human nature, we will turn to Hale’s description of what binds patronal networks.

For this, Hale cites three factors emphasized in classical studies: (1) The patron’s continued access to valuable resources for rewarding loyal clients (2) the patron’s power of enforcement, his ability selectively to deliver punishments to the disloyal…(3) the patron’s capacity to monitor clients and “subpatrons,” those figures who have clients of their own but who also are themselves the clients of more powerful be patrons.[6] These reasons can possibly work within a Marxist paradigm, but lack the obvious unit of analysis in Marxist literature: class. The listed factors seem to explain what keeps a specific patron in power but do not address what underlies the networks of patronal social relations. When class enters the picture, it can be deduced that a patron exists to safeguard class privilege, and for this reason, subpatrons endorse a given patron. Russian history has examples of Tsars overthrown by Nobles who were not satisfied with the maintenance of the feudal order. On the flip side, very powerful Tsars have been capable of brutally removing members of the Nobility in instances where their short term interests impeded the stability of the feudal order. This is important to remember when we consider Vladimir Putin’s purge of parasitic oligarchs in the late 1990s. This of course wasn’t done for the virtue of justice. It was done to establish an oligarchy loyal to the preservation of the new socioeconomic order. Oligarchs would like to maximize their self-interest, but they are content with having an unspoken rules-based system managed by the chief-patron that makes sure the ruling class plays nicely with each other.

Hale then goes on to focus on organization and resources. This is a problem in his model, as he explains that low-resource societies can still maintain patronal systems, despite the resource-draining nature of patronalism through rewards and punishments. Additionally, the problem of organization for Hale is one that recognizes that these organizations are made up of clients who carry out the rewarding and punishing and monitoring. The tautology of patrons securing the loyalty of clients when clients loyally carry out the will of patrons is resolved through the logic of expectation. Within the logic of expectation, clients obey patrons when they expect other clients to be obeying patrons. With a crude rational-choice analysis, we can understand how this works by looking at our own workplace. Oftentimes the best-case scenario in a situation is for the workers to go on strike. However, if there is a logic of expectation that inclines us to doubt the willingness of other workers to join us, we simply won’t participate in such an endeavor, as the consequences would outweigh the benefits of unlikely success.

However, when the logic of expectation breaks down, a ‘Bank-Run’ takes place. Sub-patrons break away from a patron, as happened most famously with Gorbachev. This happened because expectations and norms were so radically shaken through the new reforms that sub-patrons in the upper echelons of government made the calculation to jump ship. Instead of controlling the patronal system, the patronal system controls people, including patrons who must act in accordance with patronal laws of motion beyond their control. While it is true that social structures control people in all class societies, patronal systems control humans in a particularly vicious way.

Hale explains that “For individuals in highly patronalistic societies, what matters most for one’s material welfare is belonging to a coalition that has access to - and hence can pay out - resources.”[7] From this premise Hale then develop an analysis of patronal pyramids. A rigid patronal pyramid is one single social network that extends from the patron-in-chief to sub-patrons, to clients, going all the way down to include everyone. In this system, the rules are tight and deviation is met with brutality. Belarus and Turkmenistan are a couple examples of this formation. A second pyramid formation is a loose patronal pyramid, where things are relaxed and liberalized a tad bit. In this system, it isn’t uncommon for a sub-patron to make a move in developing their own competing pyramid. This brings us to the third patronal structure where two or more (usually just two) pyramids compete and/or coexist in the same society. Tajikistan, which is geographically divided, was the perfect example of a two pyramid structure. These informal systems serve to create formal constitutional frameworks which then act back upon the informal pyramid.

The presidential system is one such constitutional structure that is highly compatible with a rigid patronal pyramid. In the presidential system, the president almost always serves as patron-in-chief and keeps tight control of society through sub-patrons who dominate economic monopolies (whether private or state-owned, the difference is usually irrelevant), and political positions such as intelligence services, law enforcement, military, justice, and so on. Furthermore, except under the condition that the president is an unpopular lame-duck (which predictably triggers a bank-run), the president is frequently capable of maintaining one single patronal pyramid throughout the entire society.

The semi-presidential system on the other hand tends to reflect a compromised division of power. In the post-soviet space, this has been caused by either territorial considerations (ie Tajikistan), a facade used to manipulate patronal patterns of development (Putin’s power-play with Medvedev) or whenever a parity of power exists between two patrons-in-chief that cannot be resolved otherwise by means of a bloody civil war (see 2000s Ukraine). In the semi-presidential system, power is shared between a President and Prime Minister. Often each are patrons-in-chief of competing patronal pyramids.

Pure parliamentary constitutions often exist to provide the illusion of formal weakening of executive power. This of course is an illusion because real power in the post-soviet space is executed through informal networks. Regardless, changes in formal institutions can trigger changes in informal networks as expectations can change. The parliamentary system distributes power more loosely and this inevitably correlates to looser patronal pyramids. While Prime Ministers still typically function as patrons-in-chief, they operate at the behest of a parliament which acquires a greater level of autonomy and influence. Because Prime Ministers can be more easily replaced than Presidents, the logic of expectation is altered, and consequently, a looser pyramid formation emerges.

Hale's theory claims that informal networks form informal institutions which are served by formal institutions, rather than vice versa. In terms of political Marxist analysis, this is all fine and good, so long as the class component and element of class dictatorship are recognized. So does Henry Hale do this in Patronal Politics? By stressing the role of oligarchs, Hale actually makes a point compatible with a Marxist analysis by explaining how patronal networks emerged from the power of oligarchs and of state officials. This blending and blurring of state and economic lines in my view resembles the theory of state monopoly capitalism, which states that it is inevitable for governments and monopoly capitalists to fuse and utilize mutual resources for maintaining power. This seems to have occurred very clearly within the post-soviet sphere, and Hale does an excellent job of tracking the development of this process in the region. This analysis centered around oligarchic actors helps provide a behavioral understanding of systemic change.

The centering around the oligarchic class is demonstrated where Hale discusses how opportunistic actors in the Soviet Union took advantage of the market reforms. When the Soviet model was effectively dismantled, a period of hypercapitalism emerged which enriched a few at the expense of the great masses. State enterprises were sold off at a fraction of their value while neoliberal economists helped guide the transition to capitalism. The result was not only relative immiseration (wages developing a negative relationship to overall economic value creation in the whole economy) but also absolute immiseration (wages decreasing in proportion to previous levels of compensation). This process was extraordinarily pernicious in the post-soviet space. This process of mass wealth accumulation then developed an obvious relationship with political power, as guarantors of oligarchic power, ie state officials, could work within or develop their own patronal networks. Conversely, oligarchs could translate their economic power into networks of clients.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the ensuing chaos and confusion on expectations lead to a period of extreme flux, or social disequilibrium. For Hale, patronal networks took time to adjust before consolidating into systems which encapsulated the entire states they existed within. Leaders and respective clients needed to learn how to navigate the new terrain, with the most capable patrons prevailing by means of natural selection (reminiscent of evolution, a theory lauded by Marx and Engels). This section of Patronal Politics discusses the tendency for single-pyramid structures to develop in Eastern Europe in the 1990s in the context of burgeoning liberal democracies, privatizers, elite fragmentation, divided societies, civil wars and state failure, resource-poor states and to quasi-states, and so on. In each case, single-pyramids developed almost universally. Focus on and emphasis on the use of state violence to consolidate political power, hierarchical oligarchic influence, and consolidation emerging from crisis are all compatible with a Marxist outlook, but there are a few ways to take an analysis of this phenomenon further through the paradigm of Marxism. As Bukharin states in Imperialism and World Economy, “Finance capital seizes the entire country in an iron grip. "National economy" turns into one gigantic combined trust whose partners are the financial groups and the state.”[8]From this perspective, the state monopoly capitalism thesis can be further expanded using insights from Hale’s theory.

As the transition to capitalism in post-soviet Eurasia consolidated, the pool of potential contenders for state power got smaller and smaller as economic power narrowed. From there, oligarchs mostly had to develop their own class consciousness and resolve their own competing interests to establish strong states to maintain the new order. Interestingly, in the post-soviet space, this did not happen as a protracted result of market competition. This happened in one sweeping period of a few years, and the effects of this on society were immense. The brief period of wild west style capitalism after the fall of the Soviet Union immediately developed into state monopoly capitalism, and Eurasian states were mobilized to protect these interests and expand them internationally.

From a Marxist perspective, Henry Hale was absolutely correct to downplay the nature of the Color Revolutions. While bourgeois analysts praised these events as democratic breakthroughs, those with knowledge of patronal politics scoffed. These events gave the popular masses the opportunity to feel as if they were taking part in a social transformation. But they were not revolutions, but rather spectacles that coincided with the expected logic and rhythm of regime cycles within patronal politics. In the Marxist paradigm, a revolution is an event by which one class overthrows another and assumes political power. From this vantage point a ‘Color Revolution’ isn’t cogent. With no emphasis on class power or economic relations, patronal politics easily reasserts itself. The Color Revolutions exiled some leaders perhaps, but the informal networks remained and no threat of violence or force against them took place. Liberalization is not easily established within patronal system dynamics. To create the conditions for greater liberal rights, perhaps the economic prerequisites should exist first, such as the existence of a prominent middle class or labor aristocracy.[9] It is perhaps this group that is capable of expanding bourgeois right, yet the post-soviet space does not yet have a group like this in sufficient quantity.

Since Marx and Engels, Marxists have developed deep relationships with non-Marxist theories to understand them within the Marxist worldview. In anthropology, history, sociology, political science, and so on, mainstream interpretations of things have been assessed and analyzed within the Marxist canon to help increase its body of knowledge. This for Marxists is a dialectical process of intermingling with other ideas, as well as a scientific process in which theories have an objective basis to be assessed critically. In this sense, it is my view that the theory of patronalism as developed by Henry Hale could be reimagined within a Marxist context and used to help build upon Marxist political science. The reimagining process is vital, so as to not establish a theoretically incommensurable perspective which does neither the Marxist nor the theorist of patronalism, any justice. On these grounds, patronalism must be understood in the following ways to be compatible with Marxism:

First, patronalism absolutely cannot be considered ahistorically as a universal human phenomena. If a Marxist wishes to refer to Hale's theory of patronalism, it should be done almost exclusively in the context of contemporary politics. If one wishes to apply the lessons of this theory to Soviet history, one must be careful to understand the economic base and understand the deep interrelationships, structures, and systems which existed within the previous political context.

Second, an analysis of the current post-soviet economies and their relationship to the political systems is vital for a Marxist theorist. A robust understanding of the world system, imperialism, and how the average rate of profit across these economies is influencing political behavior is essential.

Third, any Marxist theorist should consider fusing theories of patronalism into a developed state theory. Instrumentalism, Structuralism, Derivationism, and the Strategic-Relational Approach all encompass possible theories in this field. In fact, the insights of such theories will help explore hypotheses in different Marxist state theories to provide evidence for and against the different theoretical models.

With these considerations in play, how can a Marxist use Hale's theory of patronalism? First, the dialectical method requires a diagnosis of contradictions within the social system. Some examples of contradictions that stand out to be analyzed and explored are the contradictions between formal and informal structures, between patrons and clients, between post-soviet states and western states, and so on. Second, the material basis of patronal logic should be uncovered. Profit rates are crucial to this, as it is the allocation and distribution of profits that maintain social reproduction. Additionally, the effects of the relative immiseration of working-class wages in proportion to economic development are highly important to look at. This is largely because this process is preventing the development of a labor aristocracy and therefore the backbone of a more liberal society. Third, any Marxist thinker must recognize their role within the context of class struggle, and not assume to be removed like an objective and neutral third party. Marxists should embrace their role in the working-class struggle and seek truth in order to change the way things are. For a Marxist, patronal politics should be thoroughly understood in order to dismantle patronal systems and establish a new social order based on working-class liberation.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Henry Hale, Patronal Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 10 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 20 ↩

- Ibid., 28 ↩

- Engels, Preface to Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884) ↩

- Hale, 31 ↩

- Ibid., 61 ↩

- Bukharin, Imperialism and World Economy (1915) ↩

- See Lenin, Preliminary Draft Theses On The Agrarian Question For the Second Congress of the Communist International (1920) ↩