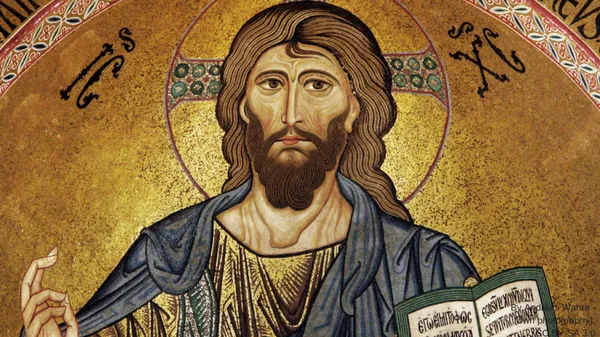

A total of 2 billion people will celebrate the holiday of Christmas this year, including over 90% of Americans. Two thousand and twenty years, according to the now universal Gregorian calendar, have passed since the birth of Jesus Christ in the Roman-occupied Kingdom of Judea. For Marxists, matters of religion have never been trivial, not least because many of the workers that must be reached with the ‘good news’ of communism retain religious faith. The doctrine of Christianity has been distorted throughout history by the ruling classes, and a fight to clarify its true revolutionary origins should be seen as important in the struggle for the popularization of scientific socialism. One thing that is clear about the Bible is that it is full of contradictions. From Paul’s initial rendering to its modern interpretations, which often completely ignore the more radical biblical concepts, there has been an extended drift away from the working-class origins of the Jesus movement. Less focused on relaying accurate historical accounts, the Church’s own historians’ main focus was on effectiveness and not truth. Peter Wollen’s interesting 1971 article, republished yesterday in Sidecar, Was Christ a Collaborator, argues that Jesus was no revolutionary but rather a collaborator with the Romans and a supporter of slavery; this seems not only contradictory with the many original scriptures, but the makeup of the early followers of Christ themselves, many of whom were former slaves, guerrilla fighters, and of the poor. Wollen bases this view on the “numerous [recorded] parables” handed down over time. For as many scriptures as you can find of Jesus and the early Jesus cult promoting a life lived in the communist fashion, you can find just as many telling people to be good slaves to their masters and subjects of their ruling state. Build the communist community but “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s”[1] and make peace with the Roman oppressors. So many contradictions, interpolations, and cherry-picked quotes from a vast body of work can make one see in the holy texts whatever is convenient to one’s own class position or worldview. Much like the many different sects of communists and socialists today, the dissident Jewish religious sects in Ancient Rome would spend much of their time arguing about very small theoretical minutia, such as: What is the essence of the Holy Trinity? Are they all separate but equal parts of God, like the U.S. branches of government, or are they all just one thing? One wins the argument by how many Biblical scriptures can be shouted at the opposition, while in the end coming to everything and nothing at the same time. To really understand the Jesus movement one needs to look closely at the historical period surrounding the events. As far away in time as it was, the first century AD is more similar to the world today than one might initially think: a vast empire ruled by the propertied classes, wantonly dominating other peoples, faced with the resistance of the plebeian classes, and particularly of colonized people. Rome was an empire that stretched from Portugal in the West to Turkey in the East. The Germanic hordes lay across the Danube, Roman units fought against the rebellious Scots and Northern tribesmen of Britain, while more storms were brewing in Jerusalem. Roman society was in a constant battle to expand its territories and further exploit their conquered peoples, mainly through enslavement and taxation. Jerusalem was at the center of the Jewish people’s struggles, although many Jews lived abroad in places like Alexandria (where about 25% of the population was Jewish) where there were also Jewish rebellions. Much like the modern left, Jewish religious organizations were marked by their countless splits and sectism. In the Talmud one can even find a quip that resembles a joke about the modern left: “Israel did not go into captivity until there had come into existence 24 varieties of sectaries”.[2] Of course, the sects’ differences in philosophies masked the real differences in the social relations between people. Take as an example the differences between the zealots, Pharisees, Essenes, and Sadducees. While the lower classes were centered around the former three, the minority upper class was centered around the powerful Sadducees. The poorest sects around the zealots and Essenes had a philosophy that the will of the people was unfree. Being alienated and downtrodden by society, they felt whatever happened to them, bad or good, was predetermined by God and felt as if they had no control over their lives. The Pharisees, who comprised a mixture of plebeian/peasant base and what could be considered a middle class, had the view that the will was free but followed a predetermined path. Sadducees, who made up almost exclusively a rich, powerful clerical ruling class based around the Temple in Jerusalem, thought the will was free and blamed the lower classes under their feet for being in their position because of some moral failing. Using the same foundational texts, different ideological groups coinciding with different social classes come to very different conclusions. The problem only gets bigger when faced with the fact that the New Testament is a collection of prophecies, parables, fables, speeches, etc., that were written decades after the supposed events happened. Due to the proletarian nature of the original community, nothing would be written down for years and would only travel by word of mouth until those with upper-class backgrounds started to join the Jesus religion. Even then, the later versions of the earlier stories written down started to have upper-class ideology seep into them. For instance, Karl Kautsky in his Foundations of Christianity calls the book of Matthew the “Book of contradictions”, and contrasts it with the earlier more revolutionary scriptures. Any sense of class hatred towards the rich was revised and stamped out. In the earlier book of Luke, Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount reads:

“Blessed be ye poor: for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are ye that hunger now: for ye shall be filled. Blessed are ye that weep now: for ye shall laugh ... But woe unto you that are rich! for ye have received your consolation. Woe unto you that are full! for ye shall hunger. Woe unto you that laugh now! for ye shall mourn and weep.”

The Sermon on the Mount according to the later book of Matthew, however, says:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven ... Blessed are they, which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.”

“Now listen, you rich people, weep and wail because of the misery that is coming on you. Your wealth has rotted, and moths have eaten your clothes. Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and eat your flesh like fire. You have hoarded wealth in the last days. Look! The wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty. You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened yourselves on the day of slaughter. You have condemned and murdered the innocent one, who was not opposing you. Be patient, then, brothers and sisters, until the Lord’s coming.”

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.