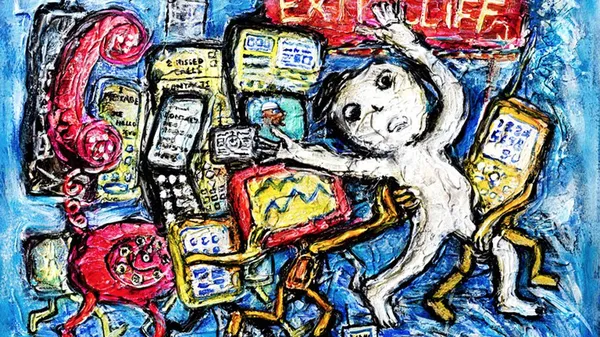

The Social Dilemma is an impressive film on how social media is affecting the way we relate to each other. Combining docudrama and interviews with former social media platform workers, the film is a mashup of the fictionalized story of a social media addict, who becomes radicalized through anti-establishment “fake news” (with no obvious left or right bent), and ends up arrested at a demonstration, and the real stories of Europeans traveling to Syria and Iraq to enlist in ISIS and white Americans joining white supremacist organizations. The film blames the present-day political radicalization on careful design choices in social media platforms which keep us hooked to the apps, and make us vulnerable to this sort of manipulation. However, like many standard left-liberal documentaries (think Michael Moore), the film presents the overview of a significant issue and suggests mild reforms to solve it while ignoring the elephant in the room: capitalism. By focusing on the neuroscience of social media addiction and how apps are designed to maximize engagement, the documentary brushes over the role market imperatives have in structuring and shaping technology to maximize profit, and ignores the way economic factors are responsible for destroying the social fabric of communities.[efn_note]See Andrew Feenberg, Transforming Technology, for a thorough discussion of when and where values are encoded into technology.[/efn_note]

Critiques of ever-increasing alienation due to the trajectory of bourgeois mass society stretch from the beginning of the communist movement through the work of critics like Theodor Adorno, Thorstein Veblen, and Guy Debord. As Marx said in The Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. […] In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation. The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage laborers.

The capitalist process of creative destruction is not a new thing, nor are the feelings of alienation from society. One only has to remember that Mark Fisher’s portrait of a broken society in Capitalist Realism was written in 2009, before smartphones were as extensively used as today.

Richard Seymour critiques The Social Dilemma in a review aptly titled “No, Social Media Isn’t Destroying Civilization.” As Seymour points out, The Social Dilemmarepeatedly fails to address capitalism and instead focuses on an epiphenomenon: the role of social media in the increasing amounts of people radicalized through the internet. It ignores the role of US imperialism, much more important than the internet in creating ISIS. The documentary’s failings are even starker with racism—social media did not create white supremacy. Racism is as American as apple pie. Even if white supremacists find each other on social media, the wide-spread economic ruin of the Rust Belt and decline in the living standards of the white petty bourgeoisie after NAFTA has more to do with Trump’s election than Facebook ads and groups.

This does not mean that we should ignore the problems of social media. In his review, Seymour rightly tackles the gaps and the catastrophist outlook of the documentary, but undersells the ways social media is actually affecting our society. Seymour is not in an easy position: he balances on a tightrope between acknowledging the massive power of social media and denying that it is uniquely responsible for the current moment. But ultimately he ends up overcorrecting against the documentary’s pessimistic assessment of social media. Seymour is correct that the neuroscience of the documentary about the way social media has addicted us is too simplistic and neuro-reductionist, but he does not sufficiently acknowledge that Facebook and friends havemanaged to addict us in a way that is unhealthy, and operate to maximize the profit advertisers can obtain from our interactions. They spend enormous sums on behavioral research for that purpose. We can always imagine better AI algorithms that will work for our benefit and mental wellbeing; under capitalism, this can at best be apps that help our mental health and overall wellbeing[efn_note]See for example, “What worries me about AI” https://medium.com/@francois.chollet/what-worries-me-about-ai-ed9df072b704[/efn_note] as long as we do not threaten, or even talk about the C-word.

To elucidate this, we can contrast Facebook with programs oriented for the corporate world for which you are paying for the software. These are qualitatively different from those whose business model is maximizing engagement. For example, Microsoft Teams incorporates features to encourage wellbeing and an “adequate” work-life balance by adding meditation to your schedule. It is not hard to imagine how a benign corporate social media that prioritizes wellbeing will end up being nothing other than self-help apps encouraging us to do yoga and to eat healthy while hiding the destructive role of capitalism.[efn_note]This is of course not to mean that we shouldn’t strive to remain healthy both physically and mentally.[/efn_note] Indeed, most of these apps are already available in your app store, with a price tag. While capitalism still drives immiseration regardless of our technological platforms, some technologies remain decidedly worse than others in their social effects.

Seymour ends his review with the question: “where is the communist program for the social industry?” Not only is this question hard to answer (and attempts at such, like nationalization of the data centers, have already been proposed[efn_note]Evgeny Morozov’s “Socialize the Data Centres!” provides a good starting point for this debate. Also check out Wendy Liu’s work, in particular Abolish Silicon Valley.[/efn_note]), but it is a higher-order question than what is needed right now. We are far from being able to affect those decisions. It is a bit like deciding how you’re going to spend lottery winnings on a ticket you just purchased. What activists must be asking right now is “what is the social industry, or even social media, strategy of our organizing?” because it is clear that social media drastically affects the way we understand organizing, the way we develop trust in our organizing, or even who gets the largest platform in an organizational debate. We must reckon with the fact that whether we want it or not, social media plays a disproportionate role in our organizing. Parties currently relate to this either by ignoring it, or by enforcing strict social media discipline[efn_note]An example of this is provided by the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) which has gone to the extreme of monitoring members’ likes on Twitter through mutual reporting.[/efn_note], and these cannot be good answers to the dilemma.

Whereas individuals can choose to unplug, our organizing will never be able to fully escape social media. We can decide to not partake, but that doesn’t stop others. The time to come to terms with this harsh reality is long overdue. We are no longer living in the times of the Bolsheviks: the difficulties of getting the message out is not just censorship, but also our signal being drowned in the noise of the hot take economy. It is easier to generate attention by calling Holocaust victims “Karens” than it is by writing lengthy critiques of the concept of race. And a second difficulty appears: are we on social media for the “social” part or for the “media” part? How much of our ego goes into making sure that it is our take that is liked, retweeted and shared, rather than the other person’s or groups’ takes? Even with the best of intentions, it is difficult to not feel good from social validation and watching our follower count or page likes go up.

The Platform and the Party

Turning back to the immediate implications of social media for communist organizing one question stands out: “should a party impose a social media discipline on their members?” It is easy to agree that some discipline is necessary: racism, sexism and any other form of discrimination should get you expelled. Likewise, an informal intervention may be needed if a comrade is having a Twitter meltdown. But the question of precisely how much intra- and inter-organization debate should be allowed on social media is not an easy one to answer. Sometimes debates happen on Facebook groups or on Twitter because there is no other platform to have them. These are responses to organizational failures and the feeling of a lack of democracy. In this case, this is a symptom of an organizational disease, and should not be seen as a lack of discipline so much as an uncontrolled explosion due to inadequate communication channels. But other times, party members simply are not happy when a party decides against them and then take to social media to protest this, or even to sabotage the decision. For instance, the infamous letter calling for DSA members to phonebank for Biden despite the National Convention and the National Political Committee of DSA deciding against a Biden endorsement. In this case the unaccountability and uncontrollability of social media following comes to the forefront.

Social media appears to flatten power structures, but what it really does is mask them. DSA-adjacent celebrities, such as AOC, have over ten times the amount of Twitter followers than the organization itself. This sets a clear boundary for accountability. Indeed, platform abuse was what caused the introduction of “democratic centralism”[efn_note]Democratic centralism can be loosely defined as “total freedom of discussion, total unity of action,” although the implementation tends to overemphasize one of these poles. See Macnair’s Reclaiming Democratic Centralism for an in-depth discussion.[/efn_note] in the German Socialist Party of yesteryear. Democratic centralism entailed that the votes, and even the speeches members of parliament gave, had to be decided on by the party as a whole. This was a means to ensure that the party controls their elected officials, rather than the opposite. The current structure of DSA prevents this accountability through democratic centralism from happening. The only event which can take place is a public repudiation, similar to the Chicago DSA’s disavowal of their elected alderman Andre Vazquez for voting for a right-wing city budget. While a positive development, it is very unclear that this has a medium- or long-term influence that is larger than the revoking of an endorsement for re-election by a similarly-sized NGO. The current individualistic electoral system is not well suited for these kinds of collective discipline. Vazquez cannot be expelled from a parliamentary fraction or removed from his seat.

Aside from politician-celebrities, social media influences our organizing in undesirable ways. Even if a large social media base does not account for a large popular base, there are still real-life ripples every time a social media celebrity decides to make others hear their opinion. Charismatic people, or even just conventionally attractive people end up having large platforms to disseminate their thoughts about what is to be done, often causing wastes of time and resources. An example of someone who has a large Twitter following due to her charisma and past involvement in politics is Briahna Joy Gray, the former advisor to the Sanders campaign. Gray, among other media celebrities launched a #ForceTheVote campaign, which attempted to pressure progressive Democratic legislators to withhold their vote for Pelosi as House Speaker unless she would accept bringing Medicare for All to a floor vote. The campaign went nowhere despite producing vigorous debates online for a few days; it lacked a real popular base beyond social media presence. Online platforms do not often translate to on-the-ground organizing and power.

The Medium is the Message

Founding father of Media Studies Marshall McLuhan argued that to understand communication, rather than focusing on particular content being transmitted, we should focus on the medium through which it occurs. He summarized this succinctly with the catch-phrase “the medium is the message.” For McLuhan, “media” is not simply audio-visual transmissions like newspapers, television or radio and communication goes beyond language. All technologies are media in McLuhan’s account because at their root they serve to extend some capacity of humanity to effect change in the environment and/or receive sensory stimulation:

“Any invention or technology is an extension or self-amputation of our physical bodies, and such extension also demands new ratios or new equilibriums among the other organs and extensions of the body.”[efn_note]Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994), 45.[/efn_note]

For instance, the transition from rail to highways as modes of transportation had profound impacts on the structure of cities, logistics networks, and broader human activities like recreation independent of what any given train or car was doing on its network. And it’s not just our social structures, but our bodies that adjust to the stimulation of our technologies. The blue light from electronic screens disrupts sleep patterns, while the consumption of convenience food is linked to heart disease and other health risks, and on a more profound level, as the Greek philosopher Plato bemoaned, our transition to written language led to a loss of our ability to remember nearly as much information as oral cultures. Moreover, every message, be it linguistic or economic, is itself a medium. A car and a train themselves are media transmitting passengers to their destinations who themselves, in the exercise of their social roles for business or pleasure, transmit messages to their destinations. Likewise, a historical television program transmits the message of a script that transmits a lesson of history which itself serves to transmit a particular moral or emotional sentiment to the general public. Media are like nested matryoshka dolls.

This especially applies to social media platforms. Off the bat, Twitter messages have a maximum of 280 characters, are evaluated by the likes of a public network, and are very rapid to send. This has a profound impact on the way the medium structures social engagement through it. Most debates will be primarily performed through rapid hits, searching the approval of the public rather than making a convincing argument. In that respect, Facebook provides a marginally better platform for debate, with unlimited length messages—and slightly more secluded commentary, but we are still judged by a large public, in real-time, and performing the debate for the audience. Moreover, Facebook comes with its own drawbacks because of the way its system of invite-only or join-request-based groups work, which create isolated bubbles often characterized by not only group-think but bizarre power dynamics and moderator cliques. What Facebook cares about is that you are engaged; being engaged because you are angry, depressed and seeking validation, or fulfilling yourself through meaningful engagement all look exactly the same to their algorithms. The same way treating disease rather than the symptoms can be seen as unprofitable for medical companies, as long as the tools of social media are dominated by the profit motive, they will maximize the profit of the company, and not necessarily the welfare of the users. Because these platforms condition what sort of media content is enacted through them, they will inevitably shape our habits of thought outside their domain. Thinking about intellectual content in the form of “takes” positions all viewpoints in relation to clout seeking and personal validation and it is increasingly common to see this terminology replace the notion of a political “line” outside decrepit sects.

Tinder might be a clearer example. What is Tinder’s service, or Tinder’s product? If Tinder were optimized to find us an adequate life companion, or at least someone to walk with us for a bit, people would use Tinder for one or two weeks, and then log off, depleting the user base. This would hurt the company. It is in Tinder’s interest to keep us logged on, replying to messages and matches, so we keep on paying our account, keep on watching the ads, and keep on giving away our data. So then, from a financial perspective it makes sense for Tinder to produce matches who provide only temporary relief from loneliness, instead of finding someone who would make us leave the app maybe not forever, but at least for a while.

On Tinder, at least one knows what they hope to get. What do we hope to get from social media aside from social-ness? With social isolation especially exacerbated in the age of a pandemic, the social media giants seek to capitalize on this. Facebook naturally tends to show people who think like us, to maximize interactions. This is where Seymour’s critique of The Social Dilemma, which focuses mainly on the power of capital, is incomplete. Social media does produce dopamine and other chemicals which give us a psychological addiction and keep us on the platform. Even avoiding vulgar materialism, it would be foolish to deny the fact that our central nervous system structures how we engage with reality. It’s not just a neutral medium. Psychedelic drugs, workplace stress, physical health, and meditation practices attest to this in their own ways. But through increased technical understanding of the regularities in the material cognitive processes in our brains, and the ability to artificially process and filter information through computers, our central nervous system itself has been extended. As McLuhan says,

The electric media are the telegraph, radio, films, telephone, computer and television, all of which have not only extended a single sense or function as the old mechanical media did—i.e., the wheel as an extension of the foot, clothing as an extension of the skin, the phonetic alphabet as an extension of the eye—but have enhanced and externalized our entire central nervous systems, thus transforming all aspects of our social and psychic existence.[efn_note]Marshall McLuhan, “The Playboy Interview,” Playboy Magazine (March 1969)[/efn_note]

Our smartphones filter spam calls, our thermostats adjust the temperature, and the weather channel tells you to prepare for snow next week. In some ways, this development of an extended, collective, electronic nervous system has cost the broad masses its antiquated faculties of self-reliance and the same concern for privacy that historically dominated the highly literate specialists and the bourgeoisie. But is this such a loss?

McLuhan notes that this new electronic way of living is much more suited to formerly marginalized cultures with strong memories and legacies of tribal existence, not the white bourgeoisie and upper-stratum of workers who financed it. Communities that had to maintain strong ties and forms of resilience in the face of colonial genocide, or forged through the hardship of the proletarian condition, are more aligned with technological logics that emphasize contextual awareness, socialness, and generalized rather than specialized knowledge. Where yesterday’s actuaries and skilled craftsmen are dinosaurs in the face of automation, a day laborer who runs several independent side hustles is more likely to have the flexibility needed to survive in an economy whose rate of change is constantly accelerating. But it isn’t the street-smart entrepreneur who is most resilient, but those who can develop strong community networks of mutual support and solidarity. The hierarchical and individualist culture of the machine age is unsuited to the conditions of life that our technologies have created when it takes Venmo micro-donations from one’s social circle to meet the rent, and a tenant union to keep the rent from rising higher. In the spirit of socialist architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller, McLuhan remarked, “There are no passengers on spaceship earth. We are all crew.”

Singing Sea Shanties on Neurath’s Boat

The present socialization methods are a contrast to those that dominated the past, but a close comparison can help us bridge the gap and develop our program. Recently on Tiktok, hundreds of videos have been uploaded of people joining in the singing of sea shanties. Passionate yet wholesome, the shared activity shines out like a beacon amid the darkness of plague and civil discord. Sparked by a viral video of a postal worker singing the song “Wellerman,” whose name’s meaning has been lost to history, a glimpse of what a healthier culture might look like flashes on our screens. But unlike earlier viral videos, this one involves widespread social participation. With Tiktok’s duet feature, people can join in song across the gaps social distancing demands.

The social context which produced sea shanties could hardly appear farther from our own: an age of heroic and well-sinewed men setting off on daring struggles with the elements and Nature in pursuit of fortune. It is an era characterized by images of widows staring longingly from the shore, great storms, and drink-sodden invalids telling tall tales to any who would listen. A time when men had no choice but to risk their lives so that their children might eat.

But is that time actually so different from our own? For all our attempts to smooth out the difficulties of life through technology, anxieties and uncertainty still beset us. Today, every time you go to work, buy a coffee, or visit with a friend, you take a calculated risk that a chain of events may result in killing you, a grandparent, or a partner. But even absent the plague, we simply tune out the 3,700 auto fatalities a day as we commute to work. “It won’t be me,” we tell ourselves, if we think about it at all. We live our lives in the face of tornadoes, floods, landslides, and other man-accelerated disasters because we must. Are the meatpackers who face a roughly 25% injury rate any less brave than the whalers or herring fishermen of old? Are retail workers who live in fear of assault by customers or mass shootings?

And yet, as much as things have remained the same, what has changed is the increased atomization and alienation of people from one another. The pandemic has only cast existing trends in sharper relief. Where the whalers had camaraderie and brotherhood, today we have parasocial relationships with twitter celebrities and podcasters. The bourgeois culture our schools and institutions force us into is incompatible with the real demands of the new techno-economic reality we face. And this has real implications for social struggle to improve conditions. As Max Dewes put it in a recent article for Organizing.work:

But all of the knowledge in the world can’t change the fact that the single hardest part of any campaign is talking to your coworkers. Almost every shortcut and miscalibration in organizing pivots around the universal truth that most workers would rather personally and publicly challenge Sundar Pichai or the President of the United States than ask Meng from accounting to have an emotional conversation about his issues at work, and pitch him on acting collectively on the job.

Where a crew of sailors might turn mutinous and maroon their tyrant captain on a rocky outcropping, today we are anxious not to hurt the feelings of our employers. Where discipline on a ship was enforced with the lash, and in the factory with the boss’s cane, today we live in enlightened times where a supervisor’s well-timed tantrum does the trick.

There was a time when the class line was more clear. Organized workers could exert discipline of their own. Scabs feared for their lives, and employers knew that driving the workers too hard would have direct consequences. But the police and national guard were always available to crack heads if workers stepped too far out of line. Organized workers had a culture apart from and subordinated to the dominant bourgeois culture of the men of letters and it played out in a low-grade struggle that involved violence in both directions.

Binding workers together and reinforcing a shared collectivity was a culture distinct from bourgeois high society and from the mass culture that united the classes. Songs sung to keep the pace at work, at the bar, and in the union hall created a shared language that reinforced an identity opposed to the boss. The Industrial Workers of the World’s Little Red Songbook acted like a passport to a world of shared meaning for those who were tired of lies told from the pulpits of corrupt preachers and in the pages of the newspapers. Visual art, poetry, novels, and plays written to advance working-class values could be found across the world and across nations. Works like Takiji Kobayashi’s Kanikosen (The Crab Cannery Ship), Robert Tressell’s The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, Daniel Alomía Robles’ El cóndor pasa (The Condor Passes), and Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children expressed the political subjectivity of the oppressed.

But not all working-class culture was political in character. Much dealt with the tragedies and sorrows of the lived reality of the times like many blues and country songs, spoke of imagined better futures, or recorded memories outside the official histories of polite society. This is where sea shanties largely sat. Singing them was a means for workers in maritime communities to enact their identities and participate in something far beyond themselves. The act of shared singing provided shared structure and narrative to the otherwise disconnected and traumatic experiences of lives on the periphery of society. The singing created a reality where sense could be made of the uncertainty of life. Is it any wonder people today have rediscovered the medium?

In his discussion of human knowledge and the nature of scientific knowledge, Austrian philosopher of science, Otto Neurath, used the metaphor of a boat to explain progress:

We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom. Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support. In this way, by using the old beams and driftwood the ship can be shaped entirely anew, but only by gradual reconstruction.[efn_note]Otto Neurath, Anti-Spengler (1921)[/efn_note]

Standing on existing scientific knowledge as a platform, researchers could replace parts of the general body of theory as they were shown inadequate or incompatible with current understanding. But the reconstruction necessarily takes as elements ideas and notions from the past, even as it seemingly discards the outdated.

This is also true with culture. There is no absolute foundation upon which a new culture can be constructed; it will necessarily be made from elements of the old. But as the ways of living and narrative structures created by capitalist mass cultural institutions like individualism, blind faith in the salvific power of scientific progress, and the civic institutions of western democracy are increasingly recognized as rotten to the core, they will be organically replaced by whatever is at hand. Even as we have to isolate through the plague, we also have to come together to survive the growing challenges and threats ecological and economic changes pose to all but the most privileged. Collective forms of cultural expression like sea shanties are a spontaneous expression of this. Socialist political art and media are a conscious attempt to address it. Both can play a mutual reinforcing role.

Even as revolutionaries focus on building direct power against the bosses in organizational and strategic terms, time and resources have to be set aside for the culture that creates political subjectivity. Whether it’s something fun like sea shanties, rap music, video game tournaments, fiction reading circles, or shared meals and recipe swapping, we have to do more than just give it space. This does not mean creating a prescriptive or top-down model of culture that excludes any “problematic” elements. Such a project is impossible beyond its undesirability. But we don’t have to be passive or tail organic cultural development either. If there’s something that needs to be said or a social need unfulfilled, revolutionaries can make conscious interventions. Our revolutionary forebears were not austere killjoys. Part and parcel with revolutions were the creation of traditions like the Soviet Haggadah, a set of prayers created by communist Jews in Russia, songs like “The East is Red” sung during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and many others.

The Social Dilemma‘s tepid reformism is a dead-end for communists, as is pretending these platforms are neutral and play no role in shaping messages. Taking note from McLuhan, we can’t simply take the existing social media and feed in communist politics and working-class culture. But that does not mean we can’t or shouldn’t engage with it. What is important is first recognizing how the technical frameworks shape the message and then adjusting our engagement accordingly. We must note that how our organizations structure their interaction with social media is more important than any particular content they post. Instead of planning and coordinating our organizations through Facebook, Google Apps, and Zoom, we can look to other platforms such as those developed by Common Knowledge. We can develop user-friendly protocols for operational security that minimize electronic records altogether or use burner flip phones and text messages, and we can develop robust policies for the behavior of organizational officers on public social media. The bourgeoisie is not all-powerful, and while their engineers do design their platforms for maximizing profit, the dynamics of social media in the real world are too complex for them to ever fully control. But the same goes for our movement too.

The traditions of dead generations may weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living, but it’s a dream workers can take control of and remake according to our own purposes. The power to do so is in your hands!

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.