Avoiding a Bullshit Future

At a time when the COVID-19 pandemic plagues both public health and the unemployment line, it has become increasingly clear that those out of work because of economic downturn or government mandate require cash on hand to meet the basic needs of life. This realization has raised the stakes of the debates over universal basic income on both the left and the right. Tied directly to discourse on automation and unemployment, there are those that have argued that the pandemic is a dress rehearsal for the employment crisis to come. As the story goes, labor-saving technologies are increasingly eliminating jobs in sectors like manufacturing that once provided a secure existence for working-class people. People began to show concern in the 1970s as the twin engines of automation and outsourcing drove people out of work and shuttered factories. The answer: send workers to school to become professionals. Of course, that response to the problem never went away. This was just the first rehearsal of Hilary Clinton and Joe Biden’s call for out-of-work coal miners to learn to code.

However, there are those who have been far-sighted enough to see that in a capitalist economy we cannot continuously create knowledge workers without roles for them to fill, or as the late David Graeber might have put it, there are only so many bullshit jobs to go around. Graeber’s theory of bullshitization coupled with his earlier work on economic stagnation offers an important entryway into leftwing debates on UBI. The basic premise of his much-celebrated essay “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit” is that neoliberalism as a political project was a response to flagging profits. Instead of reinvigorating industry, the solution to create make-work jobs and commodify all aspects of daily life through the market had the opposite effect.[1] Neoliberalism put a brake on productive investment and contributed to a long economic malaise, one that closed off from the realm of possibility what had once been imagined as inevitable. Instead of “force fields, teleportation pods, antigravity sleds, tricorders,” and “the colonies on mars” promised by the science-fiction of the mid-twentieth century, we got technology that simulates those utopian visions rather than bringing them to life. The world birthed from that project further bureaucratized life both at work and off the clock in advanced industrial economies—all in the name of managing the worst effects of economic slowdown. Graeber would probably agree with the broad strokes of how I’ve characterized his argument; where we would find disagreement is in its implication.

Graeber took the increasing recourse to political intervention into markets to mean that the laws of motion of capitalism had been fundamentally altered. He considered the possibility that capitalism in the 21st century may no longer be capitalism at all, but instead a kind of managerial feudalism. He suggests that from the 1970s forward that gains in productivity were funneled to “creating entirely new and basically pointless professional—managerial positions, usually—as we’ve seen in the case of universities—accompanied by small armies of equally pointless administrative staff.”[2] However much these administrative armies might have swelled, I would disagree with Graeber that they are all pointless, and push back against the notion that all of these changes are all part of a conscious managerial revolution, but instead arose to meet the needs of increasingly complex global circuits of capital.

Graeber’s analysis is built on a fundamental misreading of the labor theory of value, one that takes seriously a vulgar Marxian caricature that views only factory work as productive. He contends that this preoccupation with production and what is productive curbed our ability to imagine a world without value as determining the structure of social life. However, to argue that “a great deal of work is not strictly speaking productive but caring,” and that the bonds of caring often have a conservative tendency, does not deal seriously with the problems presented by the law of value, other than to point out what we’ve long known which is that it often operates behind our backs.[3] What he takes to be a sign of a move away from capitalism, Harry Braverman, whom Graeber cites, took the rise of what he calls “service” work as a sign of its universalization. As he wrote in Labor and Monopoly Capital:

The first step is the creation of the universal market is the conquest of all production by the commodity form, the second step is the conquest of an increasing range of services and their conversion into commodities, and the third step is a “product cycle” which invents new products and services, some of which become indispensable as the condition of modern life change to destroy alternatives. In this way the inhabitant of capitalist society is enmeshed in a web made up of commodity goods and commodity services from which there is little possibility of escape.[4]

As requirements for both the production and realization of capital became increasingly immense over the course of the last century, armies of functionaries were required to ensure both reproduction and expanded reproduction are continuous, blurring the line between productive and unproductive labor. Braverman argues that this obscuring of productive and unproductive work, is best represented by the stratum between labor and capital, a once privileged, but marginal group, in late capitalism they become “mere cogs in the total machinery to multiply capital,” helping guarantee accumulation can run its course, lucky only in that they aren’t wage-workers.[5] Bullshit jobs they might be, but pointless they are not.

Central to his embrace of UBI as a panacea to our social ills is precisely the fact that if we cut these crappy jobs we will be free to pursue our passions, rather than be guided by the hand of the job market. Let us also not forget that it was Milton Friedman that first proposed a UBI in the 1960s with his concept of a negative income tax, and on similar grounds too. Instead of freeing the individual from the market, it would make the individual free for the market. UBI was only one way that neoliberals like Friedman suggested we make work more flexible so that the individuals would have the opportunity to take personal risks. In reality, instead of freedom from work, neoliberalism has meant the freedom to work, especially with the rise of the gig economy. Every second not spent working is spent scavenging for the next job, the next paycheck. When one well dries up, the gig worker searches for the next oasis in the desert. In this way, labor-power is plugged as efficiently as possible into the matrix of capital, and surplus value distributed according to the specific needs of capital in general. Of course, in reality things are never that smooth, but even when they are in some sort of “equilibrium,” the life of the worker is spent solely embodying their role as a bearer of labor-power as a commodity. It is not difficult to see how this commodification is compatible with a UBI, as it would not fundamentally alter the underlying balance of class forces: capitalists would remain in control of the means of production, and workers would be left with nothing to lose but their chains.

However much we may disagree with left-wing UBI advocates, we must engage with them in good faith, which is why taking seriously the analysis of someone as respected as David Graeber is important to any critique of that project. Particularly at a time when the idea takes center-stage at an elite hobnobbing event like the World Economic Forum. Again, we only need to look to the Great Reset architect Klaus Schwab to see that plans percolating in ruling class think tanks amount to little more than a reshuffling of the deck. His plan for pushing the reset button on capitalism proposes, “governments should improve coordination (for example, in tax, regulatory, and fiscal policy), upgrade trade arrangements, and create the conditions for a ‘stakeholder economy’,” along with initiatives to promote “equality and sustainability,” and underpinning all of these plans is the ability of the public to “harness the innovations of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.”[6] How is Schwab’s plan anything more than a return to the welfare state? Even his allusion to the handling of the Great Depression as the blueprint for the Great Reset shows Schwab to be little more than a marketing consultant working to rebrand a recycled politics of yesteryear. This is not the first time he has repackaged old ideas. Take his conception of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. According to Schwab:

The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance.[7]

What are these technologies changing the world? Well for Schwab, they are the smartphone, artificial intelligence, the internet of things, and biotechnology, among others. The same simulation and communication technologies that Graeber decried as evidence of our economic anemia. How is it then, that two men with diametrically opposed ideas of progress can support the same policy?

An Answer to the Automation Discourse Factory

Answering these questions and helping to understand the discourse related to our economic future is at the heart of Aaron Benanav’s Automation and the Future of Work. Benanav’s book is punchy and short like a pamphlet but packed to the brim with important data that provides a much-needed context for these debates. According to Benanav, pundits promulgating the futuristic fantasy of mass technological unemployment are correct in their understanding that there are currently too few jobs for those that need them. Where they have it wrong is the causal mechanism. Robots are not making humans obsolete; capitalist crisis is. Rather than “a world of shiny new automated factories and ping-pong-playing consumer robots,” we are instead left with one “of crumbling infrastructures, deindustrialized cities.”[8] Benanav’s work first provides a historical context for these automation debates, so as to ground them in a materialist rather than idealist understanding of the present, one that accounts for the hollowing out of human life in the neoliberal era. Removing the technocratic utopian patina that covers these debates, he examines them in order to elucidate a path toward a post-scarcity future that is not post-work. Indeed, Benanav sees work as an integral role in any future worth realizing. As he argues in the book:

by sharing the work that remains to be done in a way that restores dignity, autonomy, and purpose to working life without making work the center of our shared, social existence.[9]

Against this vision, he provides a critique of both what he calls Keynesian demand management and universal basic income. In this way, Benanav provides a conceptual framework for Marxists to engage with this increasingly important discourse, one that differentiates itself from both the status quo and that of the fully-automated luxury capitalism peddled by technocrats and their boosters.

Beginning with the concept of automation itself, he suggests that in popular discourse automation has become a less than useful shorthand for the complete replacement of human labor by technology, a picture that is far too simple. Instead, most of the automation has been labor-augmenting technology or technologies that enhance the productivity of those using them. The consequence of these kinds of technologies is less that all human labor is removed from the equation, and more that much of the human labor required becomes superfluous. For Benanav the changes wrought by these kinds of technologies were “due not to an unprecedented leap in technological innovation, but to ongoing technological change in an environment of deepening economic stagnation,” giving rise to “persistent underemployment,” as opposed to “mass unemployment.”[10] In this sense, Benanav is commenting on the unfulfilled promise of flying cars which prompted Graeber’s essay. Of course, this sober assessment of prospects for the "future that wasn’t" did not come from nowhere. Like Graeber and many other thinkers before him, Benanav plants the roots of our problem firmly in the ground of the late 1960s and 1970s. Looking to trends in manufacturing, he breaks down the developments that have led to a long-term slowdown in advanced industrial economies. As he notes, many automation theorists have taken manufacturing as the test case for all future sectoral automation, an assumption that Benanav seeks to undermine with his own analysis.

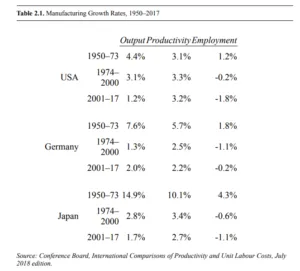

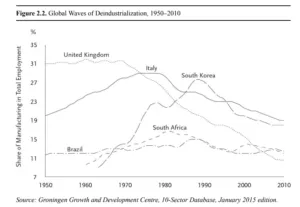

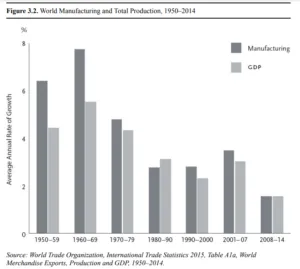

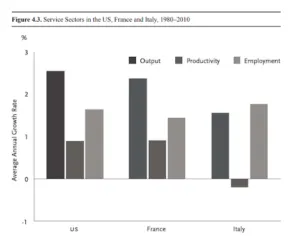

What the data he musters shows is that productivity growth in manufacturing has been relatively high against output growth rates. This is not the sign of a technologically dynamic economy on the precipice of full automation, but instead one of slowed investment that has brought productivity in line with the needs of our diminishing expectations. As the second chart shows, deindustrialization was not a phenomenon limited to the industrial core. Even so-called developing countries followed their industrialized neighbors in hollowing out their heartlands in the 1980s and 1990s with the notable exception of China. Following in the footsteps of Robert Brenner, Benanav places this development firmly in the structure of the postwar economy in which the unique historical conjuncture allowed the United States “to share its technological largesse” with friends and former enemies alike in order to promote unity against Communism.[11] In the end, this practice undermined all those involved as it led to economic free-for-alls in the same highly competitive markets. Reducing manufacturing costs became the name of the game until the incentive to invest in glutted markets became nonsensical to even the most adventurous. Faced with the assault of low-cost competition, U.S. multinationals constructed globalized supply chains in order to ensure the most labor-intensive work was moved to the Global South. German and Japanese multinationals soon followed suit, as they too began to feel the squeeze of overcapacity: a solution that has proved a brake on slowdown rather than reverse deindustrialization.[12]

It would be easy to extrapolate from this picture that the malaise of the world economy was an outgrowth of automation and the consequence of closed factories. However, this assessment is only half true. The decades following the crises of the 1970s proved that manufacturing functioned as an engine to economic growth that the service sector could not replace. Rather than provide a safe haven for productive reinvestment, other sectors have not even kept pace with the sclerotic growth of the stalled engine of manufacturing. Instead of investment in new economic activity, deindustrialization and the so-called post-industrial economy has led investors to pump up speculative financial bubbles that are still ultimately linked with the fortunes of manufacturing, even as Benanav says these markets are “oversupplied.”[13] It is for this reason that the race to the bottom for the cheapest wages has moved manufacturing geographically, from China in the 1990s and more recently to poorer developing countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh. This centralization of production to East and Southeast Asia has led to technological advancement to account for the rising wages of economic development. Once again, rather than create new technologies that allow for the full flourishing of human life, they have been narrowly applied to increasing the productivity of manufacturing.[14] That is, the building up of productive forces for their own sake, rather than for the good of humanity as a whole. Here, he echoes historian of automation David F. Noble who wrote in 1984 that rather than create a leisurely utopia, automation had not increased “the wealth of the nation but” instead led to “its steady impoverishment; not an extension of democracy and equality but a concentration of power, a tightening of control, a strengthening of privilege,” and finally,” not the hopeful hymns of progress but the somber sounds of despair, and disquiet.”[15] The economic corpse of zombie capitalism shambles on, hoping to nourish itself on what’s left of last century’s dynamism.

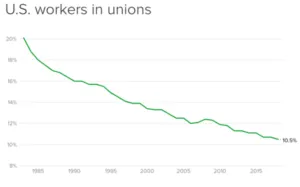

Following this analysis of economic stagnation, Benanav picks up on something that many, myself included, have discussed in detail.[16] That is, he discusses the growing concern for inflation over unemployment in the advanced industrial economies following the 1970s, a trend that has only accelerated since the 2008 recession. In those economies, the form of underdemand for labor has gone “from unemployment to a variety of forms of chronic underemployment”—a form that the old systems of measurement were not made to calculate.[17] In response to the stagflation that helped unravel the postwar order, policymakers of the 1970s and 1980s began to put focus on curing the ills of inflation over unemployment. Full employment, the lodestone of the labor-capital compact was cast aside to meet the crisis. What had been the political foundation of a generation was thrown into the dustbin of history, but not all that had been common sense was immediately discarded. Contrary to popular belief, Nixon’s famous declaration that “we are all Keynesians now” remained true even as the political order that had birthed the sentiment fell apart, something Benavav spells out more in-depth in a later chapter of the book looking at the policy prescriptions of automation theorists. In the context of understanding underemployment, it is only important to understand that the commitment to full-employment was only one political form taken by Keynesianism in the postwar era. If we look at Keynesianism as a historical phenomenon, there were two dominant strains that emerged out of the Great Depression. While both strains sought to stimulate economic activity through using the levers of the state, one sought to do so by using the corporate power of the labor movement to do so by promoting working-class welfare, whereas, the other focused primarily on using the financial incentives to lubricate commercial activity. The latter became dominant, particularly in the United States whereas historian Nelson Lichtenstein has shown, the labor movement was divided over its role in the state as the business community regained its footing in the arena of political struggle over the course of the 1940s. Lichtenstein argued that terms of postwar collective bargaining were set by the pyrrhic victory of the 1946 GM strike, which ceded worker control over industry in favor of the bread-and-butter demand of cost-of-living adjustments. This outcome, along with the failed candidacy of populist Henry Wallace dashed the dreams of many left-labor advocates, so that “social unionism gradually tied its fate more closely to that of industry and moved away from a strategy that sought to use union power to demand structural changes in the political economy.”[18]

Without recourse to state power and purged of socialists and communists, the labor movement was left to fall in line behind the Democratic Party machine. All the while union leverage at the bargaining table slowly diminished with declining profits. Leaving matters of policy to representatives of a cross-class coalitional party like the Democrats meant that those same representatives did not always act in the interests of their working-class constituents. This meant that at the same time that the labor movement lost its legs through outsourcing and automation of manufacturing, it also increasingly lost political battles that it did not have the forces to fight in the electoral arena. Much of this history provides the context for the situation of the 1970s and helps explains why labor in the United States was not prepared for the onslaught that started with the Volcker shocks unleashed under the Carter administration and continued by Reagan. However, you wouldn’t get that from Benanav’s book. Broadly speaking, this is the problem with the book as pamphlet approach, as much of the nuance gets left on the cutting room floor. On the other hand, I do think there is a broader structural problem with Automation and the Future of Work outside of missing historical context: there is a tendency to overlook the political, which I think speaks to a larger element of economic determinism in the book as a whole. By no means would I call Benavav economistic, but there is a tendency in his book to ignore the political when it does not directly relate to automation discourse. Put more explicitly, his work tends to assume that the correct or incorrect understanding of economics shapes politics, rather than the other way around.

Leaving aside this critique for now, Benanav explains that from this moment of political-economic crisis emerged our current labor regime of underemployment. Mediated by the worn and rusted remnants of the welfare state, the mass of underemployed workers exists as the modern reserve army of labor. Because employment protections and the social safety net have been made threadbare under neoliberalism, people find themselves “obliged to join new labor market entrants in low-quality jobs—earning less-than-normal in worse-than-average working conditions.”[19] This economic reality is a necessary component to a world in which services reign supreme, despite the problems with the post-industrial economy he outlines. Indeed, utilizing the work of economist William Baumol, he shows that services tend to grow by expanding employment over productivity. Growth predicated on this kind of arrangement means that without the ability to rely on increased growth elsewhere in the economy, the only way to maintain profitability is through paying workers less and asking more of them. On top of this reliance on increased exploitation, a service-centered economy compounds already-existing stagnation due to the low barrier of entry into the industry. Small-business tyrants can compete with much larger firmer because the overhead for providing service is low, particularly if they keep labor costs down to subsistence levels.[20] As he says, the poor are not necessarily getting poorer. Instead, they get more precarious. Eking out an existence becomes increasingly difficult, even as things stay the same.[21]

Moving on from his explanation of the current capitalist labor regime, he interrogates the solutions to stagnation offered up by those selling automation discourse. Benanav looks first to the Keynesian answer to the so-called automation problem. Many in the Keynesian camp emphasize the need to stimulate demand through public spending, essentially a revival of the welfare state. That approach is not all that different from Klaus Schwab's call for the Great Reset. In their view, robust social spending will induce companies to invest in revitalizing their respective countries. Benanav rejects that view on two grounds, arguing that it was not the public spending on public goods that created the affluent society of the postwar world, but rather the demand for labor was consistently driven by the growth of the private sector itself. Further, while not all Keynsians agreed on state welfare spending, there was a consistent consensus on counter-cyclical spending long after the crises of the 1970s subsided. This explains the increasing public debt-to-GDP ratios of G20 countries, with a country like the United States sitting around 103 percent. Despite this spending and increasingly low-interest rates, there is little evidence to show that those pursuing this strategy have reaped any benefit. Giving credit where credit is due, he concedes that Keynes himself and radical Keynsians were well aware that such spending would not work in conditions of what they called “secular stagnation,” instead such a situation would require socialization of industry and the adoption of long-term economic planning. The fact that very few prominent Keynsians advocate this or acknowledge what it would take to achieve let alone international scale speaks to the problems of these solutions as a political program.[22]

Sharing a vision of post-scarcity and the leisure-filled world of the radical Keynsians, Benanav argues that UBI advocates assume a similar neutral ground of state that would allow them to pass policy to realize their ideal in society. Most importantly, he contends that the myopic national viewpoint on the part of left-wing advocates means that more likely than not if we were to get any sort of basic income, it would be the minimum subsistence floor advocated by the right-wing proponents of UBI. This is because rather than distributional issues, the economic problems facing us today originate from the point of production. UBI advocates that fight for purely redistributive schemes seem to have bought into the most absurd automation PR produced by Silicon Valley executives and their coterie of hucksters and hypemen. The future is now they say. A fully-automated luxury lifestyle is out there for all those who can reach out and grab it. UBI presents itself as a way for everyone to take a drink from the overflowing cup of material abundance that grows larger by the day. The picture that Benanav has painted completely contradicts the automation agitprop of the tech industry and its boosters, its image of endless dynamism an illusion to secure its own future in a world of uncertainty. Instead, if he is correct, any “distributional struggle would quickly become a zero-sum conflict between labor and capital, blocking, or at least dramatically slowing, progress toward a freer future.”[23] Specifically, capitalists have at their disposal the power of the “capital strike—the prerogative of owners of capital to throw society into chaos via disinvestment and capital flight,” and in the case of the fight for a robust UBI over the techno-libertarian option, it would:

Quickly push the economy into crisis, forcing UBI advocates to press forward toward the post-scarcity world long before they are ready to make the leap, or else to back down. Facing such a salto mortale, reform parties typically have blinked. For this reason, it is much easier to imagine that a UBI would stabilize at a low level, as a support of an ever more stagnant and unequal society built around private property, than it would serve as a planetary highway to a world of free giving.[24]

Such a view prompts a question: if not UBI, “what is to done?” The final chapter of Benanav’s book tries to answer it by reimagining a socialist future without full automation, what it would look like and how we could get there. He does not provide a complete roadmap, but he does give us a compass to get our bearings and change our course when necessary.

Rewriting the Recipes for the Cookshops of the Future

While most of Automation and the Future of Work is concerned with a critique of automation discourse, the book’s final chapter, “Necessity and Freedom” and its postscript, attempts to provide a positive prescription for the future and a strategy for pursuing it. Rather than assume an automated future, Benanav wants socialists to imagine “a world of generalized human dignity, and then consider the technical changes needed to realize that world.”[25] What that means for him is returning to the roots of post-scarcity thinking. Tracing the intellectual lineage of this thought from Moore to Marx and Engels to DuBois and Neurath, he argues that the common denominator in their utopian visions was a commitment to the cooperative commonwealth or a society in which a free association of producers would replace the tyranny of the market. Work and its product would be planned democratically. Specialized knowledge would be made available so that the division between mental and manual labor would further democratize the sphere of production. In such a world, the development of technology would be reversed from its role in late capitalist society—from a force driving the reorganization of social life to one that is put in service of promoting human dignity and dis-alienation.

The elevation of technology to its rightful place as a tool for collective human activity would have serious repercussions for humanity. It would not completely free us from the realm of necessity, but it would provide the freedom to pursue new activities. Things that are considered hobbies today could be the work of the future. Interdependent groups of people working toward new creative projects that would allow for the full flourishing of each individual along with the collective. For Benanav, this would be a world, composed of overlapping partial plans, which interrelate necessary and free activities, rather than a single central plan,” one in which human beings would take hold over their destinies together.[26] Rather than waiting for plutocrats and bureaucrats to fix the problems of our time, we would be in a position to make history ourselves. So far so good. There is nothing in his vision of the future to quibble over. In fact, I think a cooperative commonwealth should be a North Star for the socialist movement in the 21st century. But how do go from atomized neoliberal subjects to a free association of producers? In helping answer that question, Automation and the Future of Work is far less fruitful. Benanav spends just two pages addressing how we might make reality the post-scarcity society we strive for. Lamenting how thoroughly routed the labor movement is, he finds promise in the mass protest movements that have seemed to usher in a new cycle of struggle since 2008. It is these inchoate social movements, that along with new “utopian visionaries” that have “generated new constituencies for emancipatory social change.”[27] Much like many currents within the New Left in its heyday, Benanav has taken the lack of action from the working class to mean that there will be no collective action in the future, that it has ceased to be the revolutionary subject in late capitalism. One of the problems is that he takes his analysis of decline in manufacturing to mean an indefinite downturn in working-class power. Factory workers had the ability to put pressure at the point of production that those “who give up much of their waking lives to dead-end service jobs” do not.

If this is true, why is it that he finds the piquetero tactics of blockading circulation so attractive as a form of collective action? How is this different from Amazon workers coming together to form a union which would effectively do the same when going on strike? It is because in terms of socialist strategy Benanav prefers spontaneity to party-building. In his view, the foundations of a new society will be built in “autonomous spaces that open up in the course of major struggles.”[28] Acknowledging that these mass movements still need to meet the “historic task” of conquering production, the argument seems to be that what has been lacking so far is a dream of a better world to rally behind. As he says, “movements without a vision are blind; but visionaries without movements are much more severely incapacitated.”[24] In his own estimation, to conquer the commanding heights of the economy we need both mass politics and a vision for the future that animates, and without them, we are a stumbling goliath destined to fall on our face. On the other hand, if we are simply constructing multitudinous individual models of a future society in miniature, we won’t even be able to take our first steps. Benanav is correct: we must keep a dialectical approach to our politics, one that understands that socialists need to be engaged in struggle at the same time that they are dreaming of a better world. Where I would disagree with him is the eschewing of strategy in favor of spontaneity. What is needed remains what was needed in the times of Benanav’s proponents of cooperative commonwealth. There can be no free association of producers without organizations of, by, and for workers. In my estimation that remains first and foremost the work of building new socialist unions while reforming the old existing business unions, at the same time that we work toward the creation of an independent socialist party and program.[29] Without these, we will continue to act as the left flank of liberal politics in practice and unintentionally continue to dig deeper and deeper into our own graves.

The main problem of appealing to a vague social movement politics over a specifically socialist working-class politics is that the former can easily be integrated into a politics that fails to challenge capital. To illustrate this point, I will look at a recent critique of UBI by one of the authors of The People’s Republic of Walmart, Michal Rozworski. In this piece for Jacobin, he offers up a criticism of UBI similar to my own and Benanav’s. He points out that for the vast majority of people, the COVID-19 pandemic has shattered any illusion that austerity is not a choice. Though I’m not sure how accurate it is to say most, at the very least, it has awakened many to the way their despair and dismal situations are integral to the inner workings of our political-economic reality. But his overall point is that rather than demonstrate the efficacy of UBI as a model for socialist development, it has shown to be the perfect lubricant to keep the motor of capitalism running on fumes, much in the way that someone like Milton Friedman intended it to be. If not UBI, what is the answer? In this regard, Rozworski does not sound all that different from our old friend Klaus Schwab. He writes:

The pandemic has shown tiny glimpses of a world where we do things differently. Alongside investment in immediate needs like health, education, and housing, any just exit from the pandemic will require a long period of reconstruction once the worst is over. The climate crisis is waiting at the gates and the case for a Green New Deal of public investment and economic conversion is only stronger today.

And while he rightfully understands that the way “into these bigger questions is to build on the reevaluation of essential work and essential workers that the pandemic has opened up,” there is the even bigger question of how? Rozworski is involved in the labor movement, so I don’t doubt that there is an overlap between how we think about the world. However, I would contend vague orchestrations to a left agenda without a strategy for power limit the horizons of what is possible by making demands that may both alleviate the worst suffering under capitalism at the same time that they are recuperated by the ruling class. We need to remain militantly independent as we do the work of building socialism in the 21st century, lest we fall into the same traps as our 20th-century predecessors. In that way, we can break the binary of reform and revolution that has ensnared the socialists since at least the First World War.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- David Graeber, “Of Flying Cars and the Decline Rate of Profit,” The Baffler, March 2013. https://thebaffler.com/salvos/of-flying-cars-and-the-declining-rate-of-profit ↩

- David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 180. ↩

- Ibid., 239. For a Marxist account of what Graeber might call “care” work see Richard Hunsinger’s article “The Accumulation of Affect” ↩

- Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998), 194. ↩

- Ibid., 290. ↩

- Klaus Schwab, “Now is the time for a ‘great reset’,” World Economic Forum, June 3, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/now-is-the-time-for-a-great-reset/ ↩

- Klaus Schwab, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond,” World Economic Forum, January 14, 2016. ↩

- Aaron Benanav, Automation and the Future of Work (New York: Verso Books, 2020), 11. ↩

- Ibid., 13. ↩

- Ibid., 27. ↩

- Ibid., 36. ↩

- Ibid., 38. ↩

- Ibid., 45. ↩

- Ibid., 53. ↩

- David F. Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Automation (New York: Knopf, 1984), 353. ↩

- I’ve written about this important historical conjuncture for Cosmonaut before. See “Ending the Eternal Present: A Historical Materialist Account of the 1970s” for my account of the pivotal decade. ↩

- Benanav, 56. ↩

- Nelson Lichtenstein, “From Corporatism to Collective Bargaining: Organized Labor and the Eclipse of Social Democracy in the Postwar Era” in The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930-1980, eds. Gary Gerstle and Steve Fraser (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 133. ↩

- Benanav, 57. ↩

- Ibid., 65-68. ↩

- Ibid., 70. ↩

- Ibid., 73-75. ↩

- Ibid., 85. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 86. ↩

- Ibid., 95. ↩

- Ibid., 99. ↩

- Ibid., 103. ↩

- I don’t have the requisite space here to properly address the subject of party building in detail, but comrades Donald Parkinson and Cliff Connolly have done that leg work with the articles “Without a Party, We Have Nothing” and “Create a Mass Party.” ↩