Parker McQueeney introduces two of Paul Costello’s essays on the topic of Stalin and Stalinism: Stalin and Historical Reality and Stalin and the Problem of Theory. Reading: Gabriel P.

Introduction

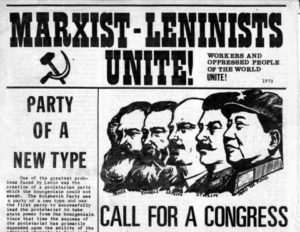

Within the New Communist Movement (hereafter NCM) – the fractured remnants of the SDS’s revolutionary Marxism-Leninism that existed outside the official Communist Party in the 1970s and early 80s – one group stands out in particular for their theoretical openness and rigor. In the wake of the Sino-Soviet split, the NCM was characterized by an uncritical theoretical poverty, seeing Marxist theory and study as an already worked-out problem, its use for communists only to apply the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and (depending on the sect in question) Hoxha to the political situation. In this period, a constellation of anti-revisionist sects competed, attempted to unite, and dissolved again into various Leninist party-building efforts as the curtains started to close on the Fordist accumulation regime of capital-labor compromise and the reactionary era of neoliberalism began. When, in 1976, Chinese foreign policy began to turn towards an alliance with US imperialism, symbolized by their support of US and apartheid South African-backed UNITA in the Angolan Civil War, a tendency within the NCM emerged that called themselves the “anti-dogmatist trend”, or simply “The Trend”. Seeing where the anti-revisionist version of “third camp” geopolitics led, adherents of The Trend backed away from following China’s hardline stance against the Soviet Union (dogmatism), without reverting to the official Communist Party’s lobbying for Moscow (revisionism). Some of these groups attempted a rapprochement in 1978-1980 but were unable to cohere for long, and The Trend faded from view after the last man standing, Line of March, imploded in 1989.

Unlike other groups in The Trend however, indeed unlike any others in the NCM (perhaps with the exception of the Sojourner Truth Organization), Theoretical Review was unique in its total rejection of Stalinism and the politics of official Communism between 1928 and 1956. Rather than applying the ‘line’ of a foreign Communist Party or solely appealing to the authority of the five ‘great heads’ of Marxism-Leninism, Theoretical Review published the modern philosophers of Western Marxism, specifically Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser, Nicos Poulantzas, Marta Harnecker, and Charles Bettleheim, using their work as a jumping-off point to develop their Marxism as an open research program rather than a closed system of correct choices in previous ‘line struggles’. The second major influence on Theoretical Review, and the more unorthodox one, explicitly in opposition to Stalinism, was the International Communist Opposition of the 1930s (known colloquially as the ‘Right Opposition’). Theoretical Review’s introspective openness and deep study of the Stalin period led them to an analysis that saw Stalin himself as a revisionist and the ICO as more in line with Lenin’s politics (an analysis supported by the historical record). Theoretical Review was probably the only New Left group in the US that studied the Right Opposition and took its arguments seriously. They published articles by Jay Lovestone, leader of the ICO group in the US, as well as documents by the ICO itself. However, their view of Bukharin, Lovestone, and the rest of the Right Opposition was not one of uncritical adulation, unlike many of the sects in the Stalin or Trotsky lineage. They also published original articles, mostly from the pen of Paul Costello, analyzing the economic debates of the 1920s and came down on the side of a more prolonged New Economic Policy, cultural struggle for socialism, and voluntary collectivization in the countryside rather than Stalin’s forced collectivization or Trotsky/Preobrazhensky’s “primitive socialist accumulation”. The following two-part article series is one example of these articles. It is a review of Charles Bettelheim’s Class struggles in the USSR. Second Period: 1923-30 (Monthly Review Press, 1978).

Despite the intellectual rigor of Theoretical Review, they were not a sterile academic journal. They were a serious Marxist publication, yes, but they were aimed at the partisans of the New Communist Movement: a publication for and by communists, not academics. Unfortunately, apart from a following within certain wings of The Trend, Theoretical Review did not significantly influence the NCM, and had to close up shop by 1983. The Stalinist dogmatism and anti-intellectual attitude stemming from a combination of the hyper-activism of middle-class guilt and American pragmatism prevented a majority of the NCM to internalize the self-critique project of Theoretical Review. It should be said that their treatment of Marxism as an open research project, their critical review of the history of Communism and especially their sympathy with the Right Opposition, and their orientation of providing serious theoretical work to Marxists outside of the academy are all things that Cosmonaut (at least aspirationally) shares with Theoretical Review. This is the first reason we chose to publish these articles, to introduce a wider group of today’s Marxist activists to this useful material. All the issues of TR have been digitized, alongside virtually every other document from the NCM, by Paul Saba (the man behind the pen name Paul Costello) and are available on the Encylopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online.

The second reason we are re-publishing these documents is as a political provocation. Despite the opening of the Soviet archives and the rise of a more nuanced historical treatment of the Soviet Union from the “revisionist historians” than what was available during the Cold War, the conspiracy theories of Stalinist politics – the claim that the Moscow Trials were legitimate, the idea that Trotsky was a fascist collaborator, and plenty of other bold and obvious lies – are being regurgitated by a small but vocal (and especially online) subsection of today’s Left, bolstered by charlatans like Grover Furr. Many on the Left today claim that arguing about Stalin and his legacy is a dead letter, and should just be avoided altogether. To not put forward a counterargument, however, is un-Marxist. Communists must have a sensitive, critical, and highly developed understanding of our own history – and the whole history of the workers’ movement – to have a chance at succeeding in our final goal. Accounting for the crimes and errors of Stalinism, frankly, accurately, and without the superimposition of a priori schemas, is a major part of this for 21st Century Marxists. However, it should be said that anti-Stalinism as the primary driver of one’s politics can lead to an unhealthy obsession that often corrodes the underlying convictions that animates one’s Marxism. Jay Lovestone’s move from the leader of the Communist Party to CIA apparatchik is just one of myriad examples. Many progressive revolutionaries of the last century from all corners of the globe were inspired by politics firmly in the Stalin continuum; we cannot simply denounce their struggles as ‘counterrevolutionary’. The contradictory role of Stalinism in world history is something Marxists have to grapple with carefully. The intellectual-militants at Theoretical Review started in this vein themselves. We present Paul Costello’s “Stalin and Historical Reality” and “Stalin and the Problems of Theory” as an example of one group that was able to overcome this theoretical and political poverty.

Stalin and Historical Reality

This review attempts to forcefully present some of the political issues raised by Bettelheim’s new book. It is neither intended as an exhaustive treatment of these issues nor as an overall review of Bettelheim’s volume. Those interested in the full importance of the book and for further details on the issues discussed in this review should study the work in its entirety.

Reliance on Stalin in defense of revolutionary Marxism is one of the pillars of the new communist movement. His picture appears everywhere in its publications, his works are quoted endlessly, he even has had organizations named after him (Youth for Stalin, Stalinist Workers’ Group). His name is linked with those of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Mao. Yet in this article, we intend to show that this reliance is based on myth, for the understanding of Stalin and his role by the majority of the new communist movement does not correspond to historical actuality. Volume two of Charles Bettelheim’s Class Struggle in the USSR only covers the period from 1923 to 1930, but it contains enough history and analysis for us to begin to dismantle the Stalin myth.

This article attempts to use Bettelheim’s work not merely to examine Soviet history, but to draw from it the necessary political lessons for the contemporary communist movement.

What functions has the Stalin myth served in our movement? Briefly speaking, we can identify four areas:

1) It has served to explain and interpret Soviet history.

2) It has served as a critique of Trotskyism.

3) It has served to uphold the revolutionary tradition in the world and in the US communist movement.

4) It has served in the struggle to defend Marxist-Leninist theoretical principles and to combat revisionism.

Leaving aside the fourth area for a separate article, let us examine the other three in some detail. We will address the elements of the Stalin myth and the reality of history, relying heavily for the latter on Bettelheim’s second volume on Soviet history between 1923 and 1930. Again, Bettelheim presents basically a theoretical-historical approach while we are attempting to draw certain political lessons from that history.

Another caution: Bettelheim understands class struggle in the party as taking the form of two-line struggles. For the period 1923-30.if Stalin was the leading spokesperson for one line, while Bukharin was the leading spokesperson for another. Throughout this review, we speak of Stalin and Bukharin and their respective “lines”, as Bettelheim presents them. By this, we do not mean to reduce Soviet history to a struggle between individuals. Rather we speak of them as representatives of definite class forces and definite trends within Marxism-Leninism.

Understanding Soviet History

The Stalin myth tells us that Stalin and the cadre around him continued, further developed, and implemented Lenin’s legacy of building socialism in the USSR, and defended it against “left” and “right” deviations.

This assertion must be examined in terms of the major two-line struggles within the Soviet state and party after Lenin’s death.

NEP and the Worker-Peasant Alliance

The most important, indeed the decisive factor for Soviet socialism in Lenin’s opinion was the worker-peasant alliance as embodied in the New Economic Policy (NEP). Lenin conceived of the NEP not as a “retreat” from war communism, or some temporary measure, but as the heart of the dictatorship of the proletariat, an active alliance between workers and peasants necessary, in his own words, “for the final establishment and consolidation of socialism.”1

Lenin saw the key to the consolidation of socialism in the USSR as the policy of the party and the working class toward the peasantry, the vast majority of the Soviet population. This could only be a policy of trust and reliance coupled with ideological and cultural struggle, the dissemination of Marxism-Leninism, and the spread of the party in the countryside. This lesson of Lenin that the peasantry had to be trusted and won over to socialism and the proletarian dictatorship found its clearest echo in the efforts of Mao Tse-tung and the Communist Party of China.

After Lenin’s death, one line in the Bolshevik party, led by Bukharin, continued to uphold the NEP, arguing that it was essential to socialist construction, to soviet democracy, and for the harmonious development of all branches of the economy. It called for a strengthening of the worker-peasant alliance as necessary for a strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat and for winning the masses to communism.

The line represented by Stalin, on the contrary, began to downplay the importance of the worker-peasant alliance, saw the construction of socialism primarily as a result of the smooth functioning of economic and administrative apparatuses, and on the external compulsion of the peasants to adopt collective forms of production. This was a conception “radically alien” to Lenin’s as Bettelheim notes.2

On this fundamental question of socialist transition, Bettelheim shows, Stalin represented those forces in Soviet society that deviated significantly from the Leninist policy of the worker-peasant alliance, a policy which was completely abandoned by 1930 with the victory of the Stalin line.

Economic Development

The question of the worker-peasant alliance was closely bound up with the question of the economic development of industry and agriculture. The basis of the NEP was the recognition that the different branches of industry had to develop harmoniously in relation to one another, that industry could only develop together with the growth of agriculture. To emphasize the growth of industry at the expense of agriculture, would not only cause great economic hardship but would also seriously threaten the worker-peasant alliance.

Bukharin repeatedly defended the Leninist line on economic development. Bettelheim says this of Bukharin’s 1928 article “Notes of an Economist”:

the article had the merit that it stressed…the necessity of not attacking the standard of living of the masses; of respecting certain objective relations between consumption and accumulation, between industry and agriculture, and between heavy and light industry; and of not setting targets which failed to correspond to the material and human resources available…3

Stalin’s conception of economic development on the other hand “ignored the need to respect certain ratios between the development of the different branches of the economy”.4 It was based on a one-sided emphasis on heavy industry and by a narrow technicist emphasis which saw economic struggle not as between capitalist and socialist relations of production but between old and new technology.

Stalin’s line, which won out, seriously unbalanced the Soviet economy, reduced the standard of living of the masses for many years after the abandonment of the NEP, seriously weakened the worker-peasant alliance, and subordinated the class struggle and production relations to the needs of technology and labor discipline.

Superstructure, State and Party

To these struggles over the future of the worker-peasant alliance, and the Soviet economic development corresponded other struggles, over the place and importance of the superstructure, the state, and the party.

For Bukharin, political, ideological, and cultural struggles were decisive for the forward motion of Soviet society. Bukharin and his supporters repeatedly criticized the unchecked growth of the state machinery and the bureaucratic apparatuses of state institutions, as detrimental to the Soviets and democracy. “The stress laid on Soviet democracy, on the role of the masses, and on organizing the supervision that the masses should exercise over the various apparatuses, corresponded to a long-standing preoccupation of Bukharin’s.”5

Equally, Bukharin criticized the growth in the party of bureaucracy and the steady erosion of freedom of discussion and critical thinking, which accompanied Stalin’s consolidation of his hold on the party apparatus. “For Bukharin there was a connection between the tendency to give up critical thought and what he saw as the gradual disappearance of collective leadership in the CC, in favor of the growing concentration of authority in the hands of one man.”6

The line and more importantly the practice of the Stalin leadership was one of applying organizational and administrative measures to an increasing degree, and of the expansion of the state apparatus, as a replacement for the activity of the masses themselves. In the party, this phenomenon took the form of a campaign for “iron discipline” and “monolithic unity”. Bettelheim explains the inevitable results of these notions:

If the “monolithic principle” is carried to its logical conclusions, the Party deprives itself of the means of uniting the broad masses, because it is led to reject, in practice, the principle of democratic centralism. This latter principle presupposes, indeed, that different ideas can be centralized after being examined and critically discussed.7

Taken together these three two-line struggles, over NEP and the worker-peasant alliance, over economic development, and the superstructure, state and party, enable us to better grasp the contradictions present in Soviet society in the late 1920s. One line, representing the advanced elements in the working class and party cadre, sought to continue and extend the worker-peasant alliance, to conduct political and ideological struggle while building the economy, and to win the peasants and backward sections of the working class to communism through patient struggle.

The other line, representing key sections of the state bureaucracy, economic directors and managers, party and state functionaries and whose spokesman was Stalin, sought to rapidly develop the economy, most importantly heavy industry, at the expense of the masses, and primarily through the strengthening of state and economic apparatuses and the extraction of a “tribute” from the peasantry.

Bukharin’s line and the forces represented were largely defeated by the year 1930. They failed to put forward a concrete plan for bringing the NEP forward into the new conditions of Soviet life and often merely repeated what Lenin had said in the early 1920s, defending it in a general way. Thus they tended to simply critique the line of the Stalin group, without presenting a real alternative for the party. More fundamentally, Bukharin had not really broken with the economist perspective nor was he willing to conduct a sharp struggle in the party and raise the issues among the masses. Preferring to remain silent and maintain their positions the Bukharin forces failed to go against the tide. This contributed to their isolation and helped the Stalin forces defeat them.

Bettelheim demonstrates that, in the debate over socialist development, which commenced with Lenin’s death and became increasingly sharp in the late 1920s, Stalin and the forces he represented increasingly departed from the Leninist thesis that the NEP was the road to socialist construction and replaced it with a policy of heavy industrialization and the extraction of a tribute from the peasantry.

Needless to say, this historical reality is not to be found in the History of the CPSU(B), that infamous work of apologetics, written under Stalin’s direction in 1939. Nor is it to be found elsewhere in the writings of American communists on this period. Until Bettelheim, the Stalin myth served to hide the truth of these years behind a mask of platitudes and abuse. But it will be asked, what about the years 1924-1927, didn’t Stalin lead the party successfully against the Trotskyists? Wasn’t Stalin’s great contribution his refutation and defeat of the Trotskyite opposition to Leninism?

On the Struggle “Against” Trotskyism

There can be no question that Stalin together with Bukharin and the great majority of the Bolshevik party leadership struggled against Trotskyism in the period immediately following Lenin’s death. This was done largely by defending, in the years 1924-26, the legacy of Lenin, the policy of the NEP and the consolidation of the worker-peasant alliance. In this struggle Stalin played a prominent and important role.

The Stalin myth has for a long time played up this role, only to grow silent about the content of Trotskyist theories of Soviet development and Stalin’s relation to them in the next period, from 1926-1930. It is this period which we want to now examine as it related to the question of Trotskyism and Stalin.

“Primitive Socialist Accumulation”

The Trotskyist theory of permanent revolution, in opposition to Leninism, viewed NEP as a temporary retreat, it denied the long term significance of the worker-peasant alliance, and insisted, in the early 1920’s that the only correct economic policy was rapid industrialization. When faced with the problem of how to finance this industrialization, the Trotskyists replied that the “capital” had to come from one source–agriculture and the peasantry.

This thesis on the extraction of capital from the peasantry to finance industrialization was labeled as “primitive socialist accumulation” by the Trotskyist economist Preobrazhinsky, after the mechanism by which capitalism itself accumulated in its early period.

In the early 1920’s Stalin strongly denounced this thesis as constituting a grave threat to the working class’ link to the peasantry. By 1928, however, with the Trotskyist threat no longer present, Stalin took up the theme himself, by putting forward the demand that the peasants pay a “tribute” to finance industrialization. This theory of exacting “a tribute” from the peasants, Bettelheim observes, “was basically, only another version of the theory of ’primitive socialist accumulation’”.8

In fact, the policy of heavy industrialization and the forced collectivization of agriculture began in 1929 was the implementation of this policy, with all the grave consequences the party had warned about when it had combatted this policy as put forth by the Trotskyists after Lenin’s death.

Distrust of the Peasantry

This policy of extracting “tribute” from the countryside was inseparably bound up with a general attitude of distrust toward the peasants on the part of sections of the party and state, an attitude which threatened the worker-peasant alliance. In the early 1920s, this distrust was expressed most clearly by the Trotskyites. Formally the party, Stalin included, repudiated their views, but such ideas never really disappeared.

Bukharin and others, including Krupskaya, Rykov, and Tomsky, recalled Lenin’s insistence that the working class had to always strive to help the peasants to go over to cooperatives and communes without the threat of coercion. Bettelheim writes: As Bukharin saw it, the future of the revolution depended on a firm and trusting alliance with the peasantry, and it was essential for the party to seek to strengthen this alliance through organizational and cultural work that took account of the peasants’ interests. He warned against the idea of a “third revolution” which would impose collective forms of production from above.9

Stalin, on the contrary, as early as 1926 was expressing his distrust of the peasantry as a reliable ally of the proletariat. He counterposed reliance on the peasants with reliance on the West European proletariat, should a revolutionary crisis develop there. This theme became increasingly popular after the world capitalist depression of 1929 began. In this way, essentially Trotskyist theses, repudiated in 1924-26 re-emerged as dominant themes in the party under Stalin in 1929-30.

Economist Problematic

The basis of their common economic policies (“primitive socialist accumulation”) and distrust of the peasantry was that Stalin and Trotsky shared something even more fundamental. Both Stalin and Trotsky were caught up in an economist caricature of Marxism, which Bettelheim calls the “economist problematic”. It is this common denominator that most sharply points up the inability of Stalin’s work and his line to stand up as an adequate critique of Trotskyism.

Bettelheim defines economism as the view that the development of the productive forces, not the class struggle, is the driving force in history. Economism enabled Stalin in the 1930s to insist that socialism had been built in the USSR by 1936 because it had attained a certain level of development in industry and production. His writings in the thirties reflect this idea that the heart of the class struggle in the USSR was the struggle to lay a material basis for socialism, rather than a campaign for new relations of production, new political and new ideological relations. Trotsky, on the other hand, starting from the same economist premises, arrived at the opposite conclusion in his The Revolution Betrayed, reasoning that the USSR could not be socialist due to the low level of development of its productive forces. Opposite conclusions, but a common starting point and methodology–economism.

Can Trotskyism be combatted from fundamentally similar premises? The answer to this question is given by merely posing it. The Stalin myth has never served as an effective theoretical critique of Trotskyism because it is the substitution of one theoretical failing for a similar one, the substitution of one myth for another. The US communist movement’s reliance on this myth has backed us into a corner with no way out: a situation which can only be remedied by breaking out of the economist straight-jacket and starting from revolutionary Marxist premises to examine the genuine Leninist trends within the Bolshevik Party in the 1920s.

Stalin and the World Communist Movement

The period 1928-30 saw a dramatic turn not only in the internal policy of the Soviet Union but an equally dramatic change in the line of the world communist movement, the Communist International. This change, like the other, was accompanied by sharp struggle and numerous contradictions. A pivotal center for this struggle was the Soviet party leadership, which was the moving force in the leadership of the Communist International. Naturally then, the struggle within the Soviet delegation to the sixth congress of the Communist International, in 1928, the decisive moment of this turn in Comintern tactics, is particularly important.

In this struggle, as in the one over the direction of development of the USSR, Bukharin, as head of the Comintern, represented the continuation of the Leninist line on the international communist, movement, while Stalin represented forces deviating significantly from Leninism.

The difference between the two lines appeared on a number of questions: the developing economic crisis of world capitalism, the characterization of the social democratic parties, the communist tactics in the trade union movement. The Stalin myth tells us that he led the struggle in the world communist movement against the “right” danger, against those who were unable to advance the communist movement in new conditions of capitalist crisis.

The Stalin view that the Western European proletariat was facing a revolutionary situation and the clear possibility of seizing state power was not, Bettelheim argues, purely accidental. Rather he suggests, it corresponded to a real need. The Stalin forces, preparing as they were to end NEP and to turn from trusting the peasants to financing industry at their expense, saw the need for a new ally for the Soviet working class to rely upon. Such an ally, they thought, could be found in the European proletariat, particularly if it could gain state power. The need for this ally, Bettelheim says, was the basis for Soviet insistence on the new line in the Communist International.

Bukharin strongly resisted this assessment and these tactics. Bettelheim declares:

for Bukharin, the development of an economic crisis in the advanced capitalist countries would not lead directly to a prospect of revolution. He thought that the metropolitan centers of imperialism would not experience internal collapse in the years ahead, and that the center of gravity of the world revolution lay in the countries of the East.10

Corresponding to this accurate assessment of the prospects of world revolution, Bukharin continued to uphold the Leninist policy of the united front, denounced the sectarian isolation line of the Stalin forces, and opposed the characterization of the social democrats as “social fascists”. In spite of this, the victory of the Stalin group in the Soviet party led to Bukharin’s removal from the Comintern and the defeat of his line, with disastrous consequences.

Stalin and American Communism

Bettelheim warns us against a mechanical view of the relation between the Bolshevik Party and the rest of the world communist movement. This view, that the history of the Comintern can be understood simply as the dictation of the policy by Stalin to the parties, is found, for example, in Claudin’s Comintern to Cominform. If parties followed the line put forward by the Soviet party, Bettelheim insists, the reasons for this must be sought in a number of factors: the social practice of these parties, their internal situation, their ability to generate criticism, and self-criticism, etc.11

Bettelheim does not make such an analysis of the CPUSA in his volume or why it faithfully followed every turn in the Soviet line, including the change in 1929. Nonetheless, the entirety of his analyses suggests some tentative comments.

The tremendous prestige of Stalin and his personal intervention in the affairs of the Communist Party, USA has, from the beginning, effectively prevented any reassessment of this episode. Two factors, one specific and one general, have also contributed to blocking such a reassessment. The first is the long and notorious role of Jay Lovestone as a professional anti-communist for the AFL-CIO bureaucracy. The second is the tradition that developed under Stalin of reading the errors or deviations of one period backward into previous periods. In this case, it was always assumed that, since Lovestone later turned into an anti-communist, therefore he must have been wrong in 1929.

This reading of errors backward into time is alien to Marxism-Leninism. It judges individuals not on the basis of their actual position and line in a definite conjuncture, but on the basis of some idealist conception of a faulty human essence. Under Stalin, for example, Bukharin, who had previously been recognized as the leading theoretician of the Communist International and a leading figure in the CPSU, disappeared from the history books. Since he was in essence an enemy of communism, as “proved” in 1938, he must have only hidden this essence in previous periods. All his earlier life, however, could then only be understood as the unfolding of that hid den essence.

Lenin himself, it must be remembered, always opposed this approach to treating political opponents. Although Plekhanov had for a long time been a Menshevik and was a violent foe of the Bolsheviks and the October revolution, Lenin never hesitated to correctly evaluate Plekanov’s role in the early period of Russian social democracy and to highly recommend Plekanov’s works written in that period. Unfortunately, this Leninist tradition was abandoned all too soon after his death.

In the case of the Communist Party, USA in the 1928-29 period, a two-line struggle which had a long and bitter history was coming to an end, in the context of the sharpening struggle internationally within the Comintern.

In addition to the international questions of the character of the economic crisis, the issue of the “social fascist” character of social democracy, and the line on the trade union question, at stake in this struggle was another issue of fundamental importance for the future of Communism in the USA. To be decided was the question: was American communism going to develop on the basis of its own analysis of the specific features of American capitalism and its corresponding class struggle, or was it going to be locked into the mechanical repetition of general formulas produced elsewhere?

One line, the party majority, was lead by Jay Lovestone, Benjamin Gitlow, and Bertram Wolfe. The other, the minority, was led by Foster, Cannon (the father of American Trotskyism), and Browder among others.

That the struggle in the Soviet party and within the Comintern leadership would spill over into the world parties, including the Communist Party, USA was unavoidable. The victory of Stalin intensified the struggle that was already going on in the communist movement as a result of his efforts against what was called “the right danger”. In the CPUSA the party majority had already been labeled as “rightists” by the minority and Stalin personally intervened in the struggle within the CPUSA in three speeches when the matter was taken before the Executive Committee of the Comintern in Moscow in 1929.

In his speeches, Stalin polemicized against the majority’s views, which he characterized as “American exceptionalism” and which he described as the notion that the USA was somehow exempt from the developing world capitalist crisis, or even of the general laws of capitalism itself. The Stalin myth tells us that these speeches were brilliant interventions, decisive in the defeat of American opportunism and in setting the CPUSA on a correct revolutionary road.

The myth notwithstanding, the polemics against “American exceptionalism” had a very different objective. At issue was not the belief by the Lovestone forces that America was immune from the laws of capitalism, but their refusal to wholeheartedly embrace the ultra-left line of Stalin in the Comintern, based on their Independent analysis of the reality of US capitalism, the recognition that America was not on the eve of revolutionary upheaval and the knowledge that sectarian practices would not build the party.

This was the real threat posed by the majority group’s leadership to the new line in the Communist International of which Stalin was spokesman. By formulating the issue as “American exceptionalism”, Stalin and his supporters insisted that the sole function of American communists was to repeat the general laws of world capitalism and the corresponding communist tactics as set forth by the Comintern executive. By definition, US capitalism could be fully understood by knowing these general laws; any attempt to go beyond the general to the specifics of US capitalism was to be viewed with suspicion, as “American exceptionalism”.

In many respects, 1929 was a turning point in the history of the CPUSA. It ended the endemic factionalism in the party, it saw the beginning of the great depression which created the conditions for a mass communist movement, and it was the beginnings of the party’s practice of the “Black Nation” line. An assessment of the campaign against “American exceptionalism” and the extent to which this campaign and its memory continued to serve as a block to creative and independent theoretical work by American communists remains to be made.

Conclusions

In turn, we have looked at the myth and the reality of Stalin’s role: in Soviet history until 1930, in the struggle “against Trotskyism”, in the context of the world and the US communist movements, all in the light of Charles Bettelheim’s new book.

At the end of each section, we attempted to summarize our conclusions. Here we want to put forward some more general theses.

1) The theory and practice of Stalin and those forces which rallied around him represented a basic departure from Marxism-Leninism:

–in its understanding of the class struggle and the transition to communism, in which it gave primacy to the development of productive forces while incorrectly appreciating the role of relations of production, political and ideological struggle.

–in its understanding of the political and ideological struggle of the party and the working class for which it attempted to substitute administrative and bureaucratic structures imposed from above.

–in its understanding of the role of the party which it subordinated to the state apparatus and its repressive agencies; and its understanding of democratic centralism, “a one-sided stress on unity and centralism”.

–in its understanding of the theory and practice of the communist parties of the world in which it replaced the concrete analysis of each party of its concrete conjuncture and tasks with the mechanical repetition of general theses and tactics.

2) The myth of Stalin has functioned in the US communist movement, in particular in the new communist movement, to block its theoretical and historical understanding:

–it has mystified Soviet history, the history of the world, and the US communist movement; blocking all efforts to critically examine the reality of that history.

–it has locked us into a theoretical-political line which not only was inadequate for the struggle against Trotskyism and other hostile currents within Marxism but which in fact reproduced many of the elements of these currents.

–it has locked us into the economist problematic, the theoretical system which has dominated world communism since the 1930s and which by failing to grasp class struggle as the key link, has impoverished and deformed all our theory and practice.

3) The dissolution of the Stalin myth, its caricature of history and the economist deviation from Marxism-Leninism and the constitution in its place of a revolutionary Marxist theoretical problematic with its corresponding critical examination of our communist history and the lessons of class struggles in the USSR is an essential task of our movement if we are to lay a solid foundation for a genuine communist party.

Stalin and the Problems of Theory

In the last issue of the Theoretical Review, we examined volume two of Charles Bettelheim’s history of the USSR in terms of its treatment of Stalin’s historical role. In this issue, we will look at the need felt by the new communist movement to defend Stalin’s ideological legacy and at Bettelheim’s critique of the Marxism of the Stalin era.

Critique of Revisionism, Defense of Orthodoxy

As is well known, the new communist movement in the USA, and internationally, arose as a reaction to and in the struggle against modern revisionism. It was clear to these early anti-revisionist communists that revisionism was growing and defining itself as a critique of the previously prevailing Marxism, the Marxism of the Stalin period. Did not Khruschev launch his revisionist offensive with a scathing denunciation of Stalin and his work?

Indeed the revisionists openly proclaimed their break with the Stalinian past and anti-revisionists took them at their word. The first reaction of the anti-revisionist movement was to take up the banner of Stalinian orthodoxy which the revisionists had abandoned. The defense of Stalin, or at least a view of Stalin different from the blanket condemnation characteristic of Khruschev’s secret speech, came to be seen by anti-revisionist communists as essential to their struggle.

Internationally, the tone for this campaign was set by the Communist Parties of China and Albania. In its polemics with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of China published a letter “On the Question of Stalin”, which defended him against Khruschev’s attacks; while from 1961 on the Albanian Party of Labor vigorously defended Stalin’s legacy.

Fairly typical of this campaign is the following quote from the Albanian Central Committee organ Zeri i Popullit of 12-21-61:

As much now as during his lifetime, Stalin’s theoretical work is of very great importance to the development and victory of the international communist movement and the cause of socialism throughout the world. It has armed and continues to arm all communists with sound Marxist-Leninist principles…(emphasis added)12

American anti-revisionists didn’t wait until 1961 to voice their own concern about the anti-Stalin campaign. In April-May 1956, almost immediately after Khruschev’s secret speech against Stalin, the New York Communist League, an organization which traced its roots back to the struggles in the CPUSA in the 1946-48 period, came to Stalin’s defense.

In an article titled “Proletarian Revolution and Renegade Khruschev (In Defense of Stalin)” they wrote:

We have to do today what Lenin had to do. We have to dig up Marxism and gather together a solid corps of comrades who…will decide to create a Communist Party in its original spirit, the spirit that moved Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. Because the distortion of Stalinism is a cover-up for the distortion of Marxism-Leninism, let us say without hesitancy that our campaign operates under the unpopular slogan: IN DEFENSE OF STALIN.13

While the New York Communist League was ahead of many anti-revisionists in this respect, by 1961-62, under the impact of the Albanian and Chinese polemics, other groups followed suit. The Provisional Organizing Committee for a Marxist-Leninist Party (POC)14, which began by defending Khrushchev, switched its position in the early sixties.

Progressive Labor’s “Road to Revolution I” in 1963 presented a defense of certain of Stalin’s accomplishments in its critique of Soviet revisionism while the Revolutionary Union did the same in their article “Against the Brainwash” in Red Papers 1. Thereafter, the more stridently the Chinese and the Albanians took up the defense of Stalin, the more their line was echoed in US anti-revisionist publications.

This defense of Stalin was seen by its proponents not simply as a moral or historical obligation, but as a cornerstone of the necessary struggle against revisionism.

Regrettably, such an assessment – that revisionism can be combatted by means of a defense of the orthodoxy which revisionism attacks – is false. Bettelheim makes this point by quoting the French communist G. Madjarian: “The fight against ’revisionism’ cannot be waged by conserving, or rather, by merely re-appropriating, Marxism as it existed historically in the previous period. Far from being the signal for a return to the supposed orthodoxy of the preceding epoch, the appearance of a ’revisionism’ is a symptom of the need for Marxism to criticize itself.”15

It is necessary to examine this analysis which Bettelheim develops in some detail.

The Sources of Revisionism and the Struggles Against It

Premise #1: Revisionism develops within Marxism as a result of a crisis in Marxism

History does not stand still; class struggles, developments in economics, politics, ideology, and the sciences proceed, whether Marxism keeps pace with them or not. When Marxist theory does not keep pace with these developments – when the practice of Marxism no longer corresponds to the needs, old and new, of the working class and its allies created by these developments – then a crisis develops within Marxism.

Three alternatives present themselves as possible “solutions” to the crisis. One “solution” is to continue practicing the existing Marxism. But this is really no solution at all to the crisis. Efforts may delay its explosion, but they cannot prevent it.

Another “solution” that presents itself is revisionism, a parody of Marxism, which seeks to “solve” the crisis by bringing the Marxism “up to date” through the introduction into it of notions, ideas, and practices of bourgeois origin at the expense of the Marxist science. This, too, is no solution, as it leads not to the strengthening of Marxism, but to its negation.

A third solution is possible, a Marxist solution, but different than the Marxism in crisis. It is a solution that calls for, in Bettelheim’s words, “the appearance of a Marxism of the new epoch” which will both criticize the Marxism in crisis and go into battle against revisionism. But communists can consciously struggle for this new Marxism only when the very character of Marxism is itself understood.

Premise #2: Marxism as it historically develops, that is the Marxism of any epoch, is not homogeneous, but consists of three distinct but interrelated elements.

Bettelheim argues that Marxism is historically constituted in each epoch and in different countries on the basis of the character and extent of the fusion between the scientific theory of Marxism-Leninism and the organized movement of the vanguard of the proletariat.16 He writes:

Marxism constituted in this way signifies a systematized set of ideas and practices which enable the revolutionary working-class movement claiming to be Marxist to deal, in the concrete conditions in which it finds itself, with the problems it has to confront.17

The three elements which go into the creation of this Marxism are 1) what Bettelheim calls “revolutionary Marxism”, or Marxist scientific thought; 2) ideological currents alien to Marxism; and 3) Marxist ideology, the ideology which guides the revolutionary workers’ movement and which has a scientific basis. The character of the Marxism of any particular epoch can be judged by knowing the relation among these elements and determining which element is primary.

All of these elements of necessity are to be found within Marxism. The science must exist to give Marxism its consciously revolutionary basis, the basis to distinguish Marxism from bourgeois ideological systems, and the basis from which practice can be guided with precision and foresight. As Bettelheim notes:

Empirical knowledge can orient action in a general way, but only scientific knowledge can give it precise guidance, enabling it actually to achieve Its aim, because such knowledge makes possible analysis, foresight and action with full awareness of what is involved.18

Yet the science is never complete, it always must be developed, expanded and rectified. And its presence in Marxism as historically constituted is always problematical, It varies from epoch to epoch in terms of the scientific principles which are incorporated and their relation to the other elements (a relationship of either dominance or subordination).

The presence of ideological currents alien to Marxism is also inevitably to be found within Marxism. Marxism arose and developed under capitalism and it cannot be immune from the bourgeois ideology which surrounds and penetrates it. As long as capitalist social relations and their corresponding ideologies exist and reproduce themselves, they will make their presence felt within Marxism.

The third element, Marxist ideology, is distinct from the others but is, at the same time, the product of them. The thinking of the working class is its ideology, the communist struggle is to win the working class to adopt the ideology of Marxism-Leninism “because it corresponds to the place occupied by the working class in production relations” and because it will enable the working class to organize and transform itself for the revolutionary struggle against capitalism.

Therefore, in addition to the class struggle between workers and capital and the struggles to win the working class to Marxism, another class struggle is going on. The site of this other class struggle is Marxist ideology, Marxism as historically constituted. The struggle is between the principles of scientific theory and the notions of hostile bourgeois ideology. At stake is the ideology which communists are using to guide and win over the working class: will it be revolutionary and liberating or will it become another form of bourgeois ideological domination.

Contrary to the idealist conceptions of the history of Marxism which see it as passing in each epoch from a lower level of theoretical sophistication to a higher one, Bettelheim presents the relationship between Marxist theory and Marxist ideology in a different light. He writes:

Marxism as historically constituted in each epoch experiences not only theoretical enrichment…but also impoverishment, through the fading, obscuring, or covering up, to a greater or less degree, of some of the principles or ideas of revolutionary Marxism.19

The Marxism of each epoch must then be evaluated not only in terms of the dominance of Marxist scientific principles, but also the degree these principles are acting to transform, advance, and deepen the revolutionary content of Marxist ideology, and combat and eliminate bourgeois ideological currents within it.

The Marxism of the Stalin Period

Turning to the history of the Bolshevik Party, Bettelheim attempts to apply this analysis to determine the character of the Marxism of the Stalin period.

“During the first half of the 1920s,” he writes, “the principle formulations issued by the Party leaders, and embodied in the resolutions adopted at the time, either reaffirmed the essential theses of revolutionary Marxism or else constituted a certain deepening of basic Marxist positions.”20

But later, after 1925-26, the changes brought about by the struggle in the Bolshevik Party and in Soviet society culminated in the victory of the Stalin group. This victory was accomplished through the defeat of the anti-Leninist, Trotskyist opposition and the remnants of the Leninist wing in the Party, led by Bukharin. Bettelheim characterizes this victory as “the reinforcement of ideological elements that were alien to revolutionary Marxism.”21 Consequently, this later Marxism, the Marxism of the Stalin epoch, which dominated the world communist movement for decades, was a Marxism in crisis. When the crisis exploded in the mid-1950s, the product of this explosion was modern revisionism.

The character of this crisis was two-fold: not only was it a problem of a Marxist ideology dominated by elements hostile to revolutionary Marxism, but it was also a problem of revolutionary Marxism, Marxism as a living science, having ceased to exist. Bettelheim goes to considerable length to demonstrate the accuracy of this assessment.

The anti-revisionists failed to grasp the nature of the Marxism of the Stalin period, its character, and its crisis. For them, the crisis of modern revisionism was caused by factors largely external to Marxism, not organic to it. For them, the defense of Stalin is a defense of essential revolutionary principles. The accurate characterization of the Marxism of the Stalin period is, therefore, essential for a correct orientation of the anti-revisionist movement, for a positive solution to the crisis of Marxism.

Economism and Mechanical Materialism

Stalin’s work Dialectical and Historical Materialism is considered by Bettelheim to be “the most systematic exposition of what gradually became, after the late 1920s, the dominant conception of the Bolshevik Party.”22 It is therefore a basic starting point for the analysis of Bolshevik ideology under Stalin.

This work is short and it should be studied together with Bettelheim’s critique. Here we can only summarize his conclusions. While revolutionary Marxism holds that class struggle is the driving force in history, the presentation in Stalin’s work has it that changes in the instruments of production determine changes in society and history. Class struggle, which is present in the “dialectical materialism” section of Stalin’s article, is entirely absent in the “historical materialism” part.

This absence, together with the emphasis on the role of instruments of production, clearly identifies the economist character of Stalinian ideology and science and economism which Bettelheim had already discussed in volume 1 of his Class Struggles in the USSR.

If, in its theory, the Marxism of the Stalin period abandoned the Leninist thesis on the primacy of politics over economics, how did this theoretical error manifest itself in the ideology and politics of the Bolshevik Party? It resulted in a mechanical materialist conception of the effects of machinery and technology on class consciousness and class struggle. An example of this, cited by Bettelheim, was Stalin’s view of the effect of collective farms on the peasantry. In 1929 Stalin insisted that the collective farms were the principal base for remolding the peasant’s outlook because they required the use of tractors and machinery. Stalin was saying, in effect, that: “it was not the peasants who were to transform themselves through class struggles… but the peasants who were to be acted upon by means of technology,”23

Unity and Democratic Centralism

While revolutionary Marxism held as Lenin put it that “the splitting of a single whole and the cognition of its contradictory parts…is the essence of dialectics,” the Marxism of the Stalin period placed unity over contradiction. One of the most significant areas where this approach produced negative results was in the theory of the party which developed in the Stalin period.

In place of the Leninist conception of the party as embodying a contradiction of democracy and centralism under the domination of the former, Stalin put forward the notion of the “monolithic party.” This notion cannot be reconciled with Leninism and democratic centralism. In fact,

If the ’monolithic principle’ is carried to its logical conclusion, the party deprives itself of the means of uniting the broad masses, because it is led to reject, in practice, the principle at democratic centralism.24

Democratic centralism presupposes that differing views will exist, that they can and will be centralized through democratic struggle. The monolithic party is founded on a denial of difference and on the practice of ruthless struggle against such differences. It is based on a sterile and purely formal unity, achieved not through ideological struggle, but by administrative pressure and expulsions.

The Party and Theory

Another area in which the thesis of the primacy of unity over contradiction led to the abandonment of revolutionary Marxist positions is the question of the relationship between the party and its theory.

For Lenin, the relationship between the line of the party and theory was always contradictory. It was always a struggle to ensure that the party’s position correctly embodied the necessary theoretical principles. In the Stalin period, however, an automatic identification of the party line with theory was increasingly fostered by the party leadership.

Bettelheim points out two negative developments flowing from this equation. First, it restricted the possibility for theoretical development because it curtailed ideological struggle (“the party is always right”) and because it concentrated authority on matters of theory in the party leadership. Second, it led the party to be less alert to new ideas and initiatives of the masses. Since the party’s line was theory (that is, correct), criticism from the masses came to be viewed with suspicion and alarm; not as a necessary element in the rectification of theory and the line, but as an attack on the party. Both theory and the line of the party were treated as absolutes, rather than as ongoing processes requiring constant development and rectification.

Theory and Practice

As mentioned above, an essential factor in the advance of Marxist ideology, in its ability to guide and serve the communist and workers’ movement in the class struggle, is that it be guided by advanced revolutionary Marxist theory. This relationship between theory and practice is at the heart of Marxism-Leninism. The abandonment of this correct relationship is therefore one of the most telling critiques of the Marxism of the Stalin epoch.

The changes in Bolshevik ideology under Stalin severely reduced the Party’s ability to “use revolutionary Marxism as an instrument for analyzing reality.”25 The political role of the Marxist ideology of the party was equally affected. Here is how Bettelheim describes it:

Under these conditions, the Bolshevik ideological formation in its changed form served, with ever greater frequency, to justify after the act the adoption of political lines which were no longer based on a rigorous concrete analysis of reality. It then functioned as a “system of legitimation”, as a grid of ideological notions which one “applied” to reality, and not as a set of concepts to he used in living analysis.26

If theory is to serve its purpose, to guide practice, it must function to creatively analyze reality. When theory is required only as a justification after the fact, its living, creative, critical faculty is quite unnecessary. The only thing required is the ability to take quotes out of context, to twist and shape them to fit the appropriate action being justified.

Conclusions

We have examined above only a few of the elements of the ideological formation of the Bolshevik Party under Stalin as presented by Bettelheim in his new book. In a review of this type, we can only summarize his conclusions in an equally abbreviated manner.

The form of Marxism that developed in the Stalin epoch, Bettelheim argues, was a kind of simplified or congealed Marxism, which departed significantly from revolutionary Marxism and constituted a caricature of it. It failed to adequately guide the Bolshevik Party in its intervention in the class struggle, and, despite the assertion of the Albanian comrades at the beginning of this article, it cannot serve the present anti-revisionist communist movement. We are back to the crisis of Marxism, but now we can also see a viable solution.

A correct struggle to develop Marxism-Leninism and to defeat revisionism is not possible by the simple return to the previous orthodoxy, the Marxism of the Stalin epoch. It can only come from a struggle to rectify Marxism in both its aspects – revolutionary Marxism and Marxist ideology.

These then are the two general tasks of the contemporary communist movement: to transform Marxist theory into a living science, through a critique of the sterile dogmatism of the Stalin epoch, and to create a living ideology of Marxism, by decisively demarcating ourselves from the vulgar Marxism of the past and the revisionist betrayals of the present.

The communist movement can and will go forward. The serious study of Bettelhelm’s Class Struggles in the USSR and its lessons can be a great contribution to that end.

- Charles Bettelheim, Class Struggles in the USSR. Second Period: 1923-1930. Monthly Review, 1978, p. 23.

- Ibid., ppS. 589-94

- Ibid., p. 411.

- Ibid., p. 413.

- Ibid., p. 423-34.

- Ibid., p. 424.

- Ibid., p. 540.

- Ibid. p. 401, 506-07.

- Ibid., p. 420.

- Ibid., p. 404.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- Turning Point, Vol. XIV, no. 6, June, 1962.

- Ibid. Vol. IX, no. #4-5, April-May, 1956.

- The Provisional Organizing Committee (POC) was a left-wing split off from the Communist Party, USA which was founded in 1958.

- Charles Bettelheim, Class Struggles in the USSR. Second Period: 1923-1930. {Monthly Review, 1978), p. 567.

- Ibid., p. 501.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 506.

- Ibid., p. 503.

- Ibid., p. 507.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 509.

- Ibid., p. 520.

- Ibid., p. 540.

- Ibid., p. 535.

- Ibid.