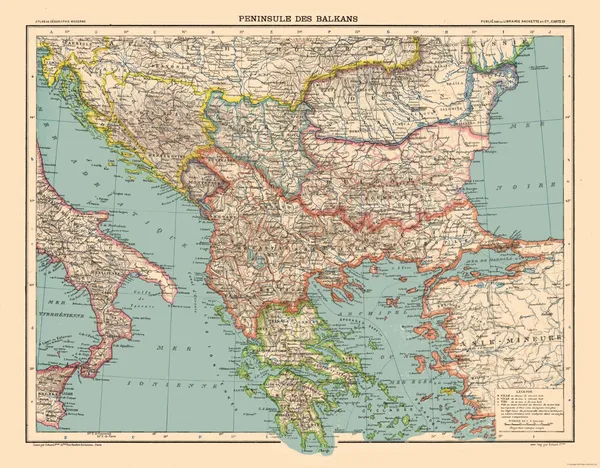

The former Yugoslav nations have one of the most storied leftist histories in the world, and most importantly, a history of resistance against the dominant powers going back centuries. It was the Balkans that first stood up to the Ottoman yoke; it was also the Balkans whose tumultuous political conditions accelerated Europe’s descent into chaos and caused the First World War. However, these historic conflicts and tensions have scarred the region, making it vulnerable to the European neoliberal machinery since the 1990s, which has caused mass migrations, extreme poverty, and a generational wave of absolute despair.

In the early 2010s, as neoliberal authoritarian regimes established themselves in power for a long time, the Balkans experienced a strong social momentum. Albeit ill-fated, this "Balkan spring" left deep traces, even when the desires for radical social change were thwarted by an ongoing exodus that is emptying the region.

In February 2014, thousands of privatized company workers who had not been paid their wages for months rebelled. The movement originated in the industrial city of Tuzla, in northern Bosnia and Herzegovina, and soon spread throughout the country to all communities. Defiant in the face of trade unions and political parties, the protesters organized in "citizen assemblies" and thus began an experience of direct democracy. Everywhere, protesters clamored: "Hunger is spelled the same in Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian", a far cry from the dominant image of the Balkans, always associated with the wars of the late twentieth century and the ghost of national and “ethnic” fragmentation that had generated endless conflict. Indeed, even if the traumatic memory of the wars is still present, the countries of the region face other challenges: those of a neoliberal "transition" that, since it had been "delayed" compared to that of the other post-socialist countries, was only more violent and driven by authoritarian, predatory elites with the backing of the European Union. Whether they are members of the EU, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania and Slovenia, or just candidate members which are more or less advanced in the long integration process, the Balkan countries belong to a southeastern periphery of Europe. This is exactly why it is important to study the social and political turmoil in this particular region, since it exemplifies how the neoliberal order, in this case that of Europe, creates a subordinate group within’ itself, and how these “second-class” Europeans fight back, while also dealing with a centuries-long heritage rooted in ethnic, national and religious divides.

The Difficult Resurgence of the Balkan Left

The wars of the 1990s delayed the processes of liberal "transition" in the republics that emerged from the outbreak of socialist Yugoslavia, while neighboring Albania seemed trapped by a dynamic of self-destruction with the revolts of 1997. After this 'lost decade', in the early 2000s the Balkan countries embarked on their path of 'transition'. While the Dayton peace accords had ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in December 1995 and Kosovo had been under the protection of the United Nations (UN) since June 1999, the entire region seemed determined to turn the page on warmongering nationalism with the electoral defeat of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) in January 2000 and the fall of the Serbian regime of Slobodan Milošević in October that year.

In June 2003, the European Council in Thessaloniki stated that all the Balkan countries were "in a position" to join the Union, but without considering joint accession or setting a binding timetable: one after the other, these states had to "pass the test" by following a program of severe reforms capable of transforming them into functional liberal democracies. Apparently, it was time to start a true cultural and anthropological revolution, the "Europeanization" of the Balkans. At the end of the Kosovo war, British Prime Minister Tony Blair had even mentioned a much more ambitious goal, that of "de-Balkanizing the Balkans".[1] In a civilizing vision with neo-colonialist overtones, an attempt would be made to rid the region of its "structural" defects — bad administration, authoritarianism, corruption, unpunctuality, an excessive taste for strong alcoholic beverages and blood feuds — so that it finally had access to the glorious western modernity, which rests on the sacrosanct pillars of economic and political liberalism, perceived as the ultimate horizon of History.

The Balkan countries, therefore, committed themselves, delayed but with lively enthusiasm, to the application of the classic neoliberal recipes: massive privatizations, transfer of public services to public-private alliances, feverish expectations of fabulous foreign investments that never materialized. However, neoliberal policies enjoyed broad consensus within the political elites of the region: they had the support of both the Nationalist forces and the still-powerful Social Democratic parties of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, or Macedonia, direct descendants of the former communist apparatuses.

At the beginning of the 21st century, political life was structured around an opposition between pro and anti-European forces, the latter opposed to integration with Nationalistic arguments, mostly "moral", identitarian or religious arguments, as the Union was perceived as a bastion of a cultural liberalism that challenges the "traditional" values of the societies that are candidates to join the club. They did not question the liberal model at all. The major political confrontations revolved around the trial of war criminals and cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), based in The Hague, but also symbolic cultural objectives such as the visibility of LGBTQ communities: the first gay pride marches in Belgrade or Zagreb ended in pitched battles between the police and far-right groups seeking to attack protesters.

Nevertheless, integration finally prevailed as the only option for the region. In 2003, the Croatian HDZ undertook a pro-European aggiornamento under the leadership of Prime Minister Ivo Sanader. It was, however, in Serbia where the most spectacular turn occurred. While the far-right Serbian Radical Party (SRS) was hitting a “glass ceiling” of around 35% of the vote, the main leaders of this movement, Aleksandar Vučić, and Tomislav Nikolić, left the "old house" to create a new Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), which presented itself as a conservative, pro-European group. Success, favored by strong Western support, quickly knocked at their door: the party came to power in 2012 and two years later secured an almost hegemonic position. After being Prime Minister, Vučić became President in 2017, as the SNS joined the European People's Party (PPE), which brings together the continent's conservative groups.

Paradoxically, this pro-European consensus of the political and economic elites of the Balkans came about right at the moment where the real prospect of integration was waning as a result of the economic crisis and the political and institutional crisis that were corroding the Union itself. The Balkan nationalists not only became 'pro-European' at the very moment where the process weakened, but they also lost their performative capacity, their power to effectively advance the societies of the candidate countries. It was a very particular deal that took place: while the EU was no longer in a position to offer a real perspective of integration to the Balkan countries, it was content with the coming to power of regimes that held a formally "pro-European" discourse, even when their practices were characterized by a capture of the rule of law, a deepening authoritarian drift and systematic clientelism. They became "pro-European" precisely because they clearly understood that Europe would demand nothing of them.

The first effect of this pro-European turn by the Nationalists was the discomfort of the Social Democratic movements: indeed, integration represented the most important part of their program, a flag that was now disputed by the nationalists. In Serbia, the Democratic Party (DS), a member of the Socialist International, began an endless descent into hell from the moment Vučić's SNS seized its ideological "goodwill". Albania’s political evolution is very similar to that of Serbia: Edi Rama became Prime Minister in 2013 and put forward a system of hegemonic control of society comparable to the one his "friend" Vučić established in the same period in Serbia. In addition, both men show off their closeness, presenting themselves as guarantors of "regional stability", even though one comes from the Serbian Nationalist far-right and the other continues to lead the Socialist Party of Albania: beyond the labels, no ideological difference separates them.

Fatos Lubonja, a former political detainee of the Enver Hoxha dictatorship and a leading figure of the Albanian intellectual left explained that “After the fall of the Stalinist regime, Albania lived for a long time to the rhythm of a strange competition that was called bipartisanship. The political-mafia interests were divided into two camps; some supported the Democratic Party (PD), others the Socialist Party, that is, the direct heir to the old Labor Party”. “In 2013, Edi Rama went all in: he promised everything to those hidden interests, which control the economy and the media, and they joined him, offering him an unappealable victory. Since then, he believes he is immovable”. This strange status quo, from which the Balkans have not yet freed themselves, nevertheless opened up a new political space in which the European question ceased to be an ideological indicator, as they all became nominally "pro-European".

An ever-delayed “Balkan Spring”

This strengthening of autocratic systems took place in 2013-2014, after years of intense social turmoil, while the Balkans were being hit by the global economic crisis. Indeed, at the beginning of the 2010s, the region experienced important waves of political and social protests, in which democratic demands intersected with real hunger revolts, as it did in Bulgaria in 2013, or during Bosnia and Herzegovina’s assembly movement the following year.

Undoubtedly, the first sign came from Croatia, which saw the emergence of a powerful student movement in the fall of 2009, while the country, a few years after its accession to the EU, formalized in 2013, was seeking to finish its process of adaptation to European standards and, in this case, to the Bologna Accords that regulate higher education. The latter included the obligation to pay registration fees, when university studies were until then free in Croatia. By denouncing this measure, the movement quickly put into question the entire neoliberal approach to education, but also the process of European integration. It temporarily pushed back the government, but it served above all as the first political experience for an entire generation, the first truly "post-Yugoslavs” born around the time of the collapse of the old Federation. This movement had a distant echo ten years later in Albania, where the student revolt in the winter of 2018-2019 pushed back the Rama government. In this case, it was less about opposing the Bologna Accords than about direct privatization of public higher education.

One of the strongest waves of protest erupted in quiet Slovenia in the autumn of 2012. This small and prosperous country of two million people, the only one of the former federated republics that managed to escape almost completely from the armed conflicts of the 90s and joined the EU in 2004, was experiencing the consequences of the world crisis in its own way, with a controlled external debt and an unemployment rate that was always below 10%; a situation incomparable to that of the other countries of "Southern Europe" — Greece, Spain or even Italy. The catastrophic speeches of Conservative Prime Minister Janez Janša, who announced in the autumn of 2012 the nearly imminent bankruptcy of the country, were mainly aimed at justifying adjustment measures and ending the rather privileged social model that Slovenia had managed to preserve until then. The still powerful unions mobilized, while protesters vilified the EU by often waving the flag of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and even holding the portrait of Field Marshal Tito.[2]

It is not surprising that this first significant return of Yugonostalgia on the political level took place in Slovenia. The republic was already very prosperous in the days of the common State; the Yugoslav model of self-management was largely experienced in Slovenia[3] and, most importantly, its departure from the Federation happened almost without violence, and thus without bloody trauma. Until then, Yugonostalgia was expressed in a romantic or folkloric way, with the resumption of manifestations that were interrupted for two decades, such as "Youth Day'', every May 25th, or the increasingly numerous attendance to the commemorations of the great battles fought by partisans in World War II.[4] Yugonostalgia became a political reference, a model, of course idealized, of opposition to the corrupt Nationalist elites: the portraits of Tito raised during the demonstrations in the winter of 2014 in Bosnia and Herzegovina were also quite numerous.

This reference to Tito and Socialist Yugoslavia was validated for a number of reasons. Unlike the other countries that practiced so-called "real socialism", the Yugoslav Socialist experience continues to be perceived in a positive way, with the memory of good living conditions, freedom of movement, and the pride of having belonged to a country respected on the international scene. Yugoslavia's famous "red passport" was one of the most sought-after in the world, as it allowed visa-free travel in both Socialist and Western European countries and in almost all countries in Africa and Asia —This comparison does not favor the passports of the successor states —, while the political monopoly of the League of Communists was satisfied with vast spaces of intellectual or artistic freedom. This memory of Yugoslavia is mainly associated with the final period of the Federation, the 1980s, characterized by a rapid improvement in material well-being, at a time when the dangers would drag the Federation (indebtedness, tensions between the bureaucracies of each of the Federated Republics, deepening of internal differences in terms of development, etc.) were about to worsen. Those who lived through this period retain an idealized memory, while the youngest dream of a golden age...

Only Kosovo constitutes, to a certain extent, an exception, as there is the least natural "Yugoslav" reference as a consequence of the Albanian-Serbian tensions, although there is also the temptation to idealize the "beautiful years" of the autonomy of this province (reduced to the period between the constitutional reform of 1974 and the demonstrations of 1981). In the "market of utopias", the Yugoslav reference remains, in any case, the only one available: nationalism tragically showed its limits - not only due to wars, but also due to the sea of corruption in which all the nations’ "Patriots" of the 1990s sank, whether in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina or Kosovo. And the hope of a European "normality" is failing at the same time that the prospect of integration is fading.

However, the references of the Slovenian protesters of 2012, like those of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2014, were not limited to this idealized Yugoslavia, but were inscribed in a European and World cycle, for instance, Croatia also had its indignados movement, in 2011. The explicit reference to a "Balkan spring", echoing the Arab springs, was quickly formulated, while observing the experience of other movements, be it Occupy Wall Street or the violent protests that shook Greece. Despite the relative geographic proximity, Greek influence remained relatively limited, and Syriza, like the other movements of the Greek radical Left, never sought to develop networks in the Balkans. The spectacle of the Greek fall, however, put into question the convictions of the most optimistic Europhiles: how to reconcile the dream of prosperity linked to European integration with the bitterness of the adjustment measures imposed by the Troika?

Dreams of a Balkan spring quickly faded, as the EU welcomed the coming to power of "strong regimes" such as Rama in Albania or Vučić in Serbia. Indeed, they represented the best guarantee against the risks of social explosion; they were a guarantee of "stability." The gaze of the "international community" on the social demands of the beginning of the decade was categorical. In February 2014, when the assembly movement broke out in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Austrian Valentin Inzko, did not seek a dialogue with representatives of the protesters, but requested a reinforcement of the military troops of the European mission EUFOR-Althea, in order to face the risk of "destabilization" of the country. This official, appointed by the EU, had the mission of ensuring respect for the provisions of the Dayton Accords, but also promoting the resurgence of a "multi-ethnic" society in the country. However, in the face of the demonstrations that brought together all the communities, what he saw was the risk of social subversion.

The Defense of Public Spaces

Throughout the decade, new forms of mobilization emerged, with struggles waged in defense of public spaces against tourism investment or urban renewal projects that entailed their privatization: mobilizations in Dubrovnik against the creation of a huge tourist and residential complex in Srđ Hill, which included two golf courses, with the slogan "Srđ je naš" [Srđ is ours]; against the huge Skopje 2014 urban projects in North Macedonia, or the Belgrade Waterfront, in Serbia. In addition, all of these projects were suspected of serving as fronts for dirty money laundering. Important mobilizations were also carried out in defense of the environment, against air pollution, which reaches catastrophic levels in the big cities of the Balkans[5], or even against the construction of dams and small hydroelectric power plants in the virgin rivers of the region. Financed by the EU for a long time, these constructions often resemble green-washing operations involving capitals of very murky origin that also cause irreversible environmental damage. In Albania, as in Bosnia and Herzegovina or Montenegro, it was the rural communities that mobilized.[6] “We lost everything with the transition. There are no more factories or jobs, ”explained defenders of the Sinjajevina ecosystem in northern Montenegro. “We only have nature and the water that flows from the mountains. Now, they even want to take that away from us…".

In Kosovo, during the winter of 2015-2016, the sovereignist left movement Vetëvendosje! [Self-determination!] organized strong and violent demonstrations against the content of the economic agreements that were under negotiation with Serbia. This movement, which enjoys enormous support among the youth, articulates Albanian nationalism, denounces the corruption of ruling elites and makes a radical critique of Western interventionism in the internal affairs of Kosovo. Led by a charismatic leader, Albin Kurti, Vetëvendosje! is also widely accepted in Albania or in the Albanian communities of North Macedonia, but its nationalism prevents it from spreading further and even complicates its relations with the other leftist groups in the region.[7]

These mobilizations also found their limits in the mass exodus that affects all the countries of the region and that intensified in 2014-2015. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, this phenomenon, of an unprecedented dimension since the end of the war, is very directly linked to the loss of hope as a consequence of the failure of the assembly movement. In 2015, in the space of a few weeks, between 7% and 8% of the inhabitants of Kosovo left for Germany, a movement of panic completely unprecedented in times of peace. However, it is not the poorest who leave, but professionals or people with recognized technical skills who can easily find jobs and legalization documents in Germany, whose labor needs seem permanent, whether they are health professionals or construction workers.[8] The leaders of the region see this exodus favorably: it makes it possible to artificially reduce unemployment figures, find a way out of social pressure, while those who leave could mobilize for change. Both in Serbia and in Kosovo, as well as in North Macedonia, the same banners were waved: "I'm going out because I don't want to go." A few months later, those who wore them frequently embarked on the path of exile. This demographic drain played an important role in the exhaustion of the protest movements and continues to affect all prospects for change.

Despite this, the emergence of a new political alternative was possible. In Slovenia, the Združena Levica (United Left) coalition obtained its first representatives in the National Parliament in 2014. Converted into Levica (The Left), it strengthened its positions in 2018 by collecting around 10% of the votes. Elsewhere, it was mainly movements of municipalist origin that, inspired by the numerous demonstrations in defense of public spaces, finally participated in elections, such as Zagreb je naš (Zagreb is ours) in Croatia, or Ne da (vi) mon Beograd (Let's not drown Belgrade) in Serbia.

In Croatia, these municipalist currents, gathered in the Možemo (We Can) platform, managed to ally with other left forces, whether they were disappointed — and rather aging — militants of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) gathered in the Nova Ljevica (New Left) or those more radical of the Radnička Fronta (Workers' Front). This environmentalist left-wing coalition surprised in the parliamentary elections in July 2020 by winning seven of the 151 seats in the Sabor, the Croatian Parliament. In the Zagreb constituency, Možemo's candidates prevailed over those of the Social Democratic Party; in Rijeka, the Social Democratic mayor was defeated by the leader of the Workers' Front, Katerina Peović. This victory, which no pollster had foreseen, allows us to predict new victories in the municipal elections of 2021, even when relations between the two main components of the coalition - Možemo and the Workers' Front - have since deteriorated greatly.

Paradoxically, the coronavirus crisis could indeed re-shuffle the cards in an unexpected sense. At first, in the spring of 2020, as in all parts of the world, the epidemic allowed the Balkan autocrats to reinforce the authoritarian character of their regimes in the name of sanitary demands,[9] but it also had another notable effect by forcing the return of migrants or forcing those who had not yet left to stay. These are active young people, little suspect of being sympathetic to the current regimes, to whom they owe nothing, and whose frustrations are heightened by the context of the pandemic. Their massive presence certainly played an important role in the anti-government demonstrations that shook Bulgaria in the summer of 2020, and also influenced the results of the different elections held that year, be it the parliamentary elections in Montenegro on August 30, 2020 or of the municipal councils of Bosnia and Herzegovina on November 15.

In Montenegro, it was the veteran of Balkan politics, the immovable Milo Đukanović, in power since 1989 and a privileged ally of the West despite the organic ties between his regime and organized crime, who suffered the first electoral defeat of his extensive career. His Party of Democratic Socialists (DPS) - which is way less "democratic" than "socialist" - was defeated by an opposition, ideologically heteroclite of course, but that managed to form a government and initiate a radical purge of the State apparatus. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the ruling parties suffered a series of setbacks, particularly the Muslim Bosnian Nationalists of the Democratic Action Party (SDA), defeated in Sarajevo by a coalition between the Social Democrats and Naša stranka (Our Party), a hybrid group comprised of everything from a liberal social wing to municipalist currents that are very committed to the defense of public spaces, such as the struggles against the privatization of wáter.

The case of Albania, once again, presents its own dynamic. While a leftist reference seemed impossible to sustain in this country due to the enormous weight of the Stalinist heritage and political life being reduced to a clientelist confrontation between the Democratic and Socialist parties, a small handful of militants disrupted the situation. Claiming Marxism-Leninism, the group Organizata Politike (Political Organization, OP) played a central role in the 2018-2019 student movement, but also in the struggle of the Bulqizë copper miners in 2019 or in the creation of the first Union of Call Center Workers, an industry that’s highly developed in Albania to cover the Italian market.[10] OP is also very present in feminist and LGBTQ struggles. In a society devastated by the violence of the transition, but also by the exodus, where there are not even unions worthy of the name, this small group has much to rebuild, and it does so according to the classical principles of Leninism, ensuring the theoretical formation of its militants, but has not yet tried the electoral experience.

To Think from the Periphery

In May 2020, in the midst of the coronavirus crisis, when an EU summit was to be held in Zagreb, numerous civil society organizations from the candidate countries of the region made a call to demand true democratization, linked or not to European integration.[11] While many actors in social mobilizations had long postponed their hopes in this regard, they now understand that they cannot rely on themselves alone to finally see a change in their societies. These militants also understood that the other countries that are already members of the Union shared a common destiny with those who are still candidates: that of belonging to a marginalized periphery of the European "center" — formal accession did not change anything about this position, as revealed by the examples of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007, or that of Croatia in 2013. Indeed, what place does the Union reserve for the Balkan countries? From the point of view of Brussels, only the "stability" guaranteed by the local autocrats' counts; the geopolitical objectives of the region are essentially reduced to the security dimension: the risks linked to Islamic radicalization and, above all, migration. In 2015, more than a million people embarked on the 'Balkan route', and this remains, despite its theoretical closure in March 2016, one of the main routes linking the Near East with Western European countries. The mission of the Balkans would be above all to serve as a buffer zone, a glacis that protects "Fortress Europe." The region also has the dual mission of providing cheap and skilled labor to Western countries that need it, such as Germany, which means maintaining a minimum level of quality in public educational services, but also hosting offshore workshops, away from the "center" countries.

In this context, several left-wing organizations (The Left in Slovenia, the Workers' Front, and New Left in Croatia, the Party of the Radical Left in Serbia) adopted in July 2020 a "Declaration on Regional Solidarity" that highlights the values of solidarity, anti-fascism, feminism and the defense of social rights.

The utilitarian vision of the Balkans promoted by the EU is in fact far removed from the hopes of democratization and social harmony long linked to the goal of integration. The Balkan countries must reinvent the paths to follow, which also presupposes the recovery of their political subjectivity. The post-COVID-19 world is likely to be a post-European Illusion world as well and in this unprecedented context the most unexpected trends may emerge. In Montenegro, the Orthodox Church has played a decisive role in the dynamics of democratic change, while Kosovo is witnessing the rise of a Nationalist Left with the aforementioned Vetëvendosje! Movement and its charismatic leader Albin Kurti, who won a real victory in the parliamentary elections of February 14, with almost 50% of the votes and the security of forming the new government. Vetëvendosje! is in many ways an atypical movement. Made up of radical left activists with a strong political culture, it professes, at the same time, an Albanian Nationalism that has long kept it at a distance from other left-wing movements in the region. This synthesis between leftist commitment and strong social concerns, a marked criticism of international forms of tutelage, including that of the EU, without forgetting the overwhelming weight of a charismatic leader, evokes, somewhat unprecedentedly in Europe, the left-wing populisms of Latin America. It remains to be seen if Vetëvendosje, once in government, will succeed in carrying out the policy for which the electorate voted it in. In any case, the magnitude of its victory opens up a lively debate among all the left-wing forces in the Balkans.

This article was originally published in the magazine Nueva Sociedad 292, Marzo - Abril 2021, ISSN: 0251-3552

https://nuso.org/articulo/el-dificil-resurgimiento-de-la-izquierda-en-los-balcanes/

Jean-Arnault Dérens is Editor-in-chief of the magazine Le Courrier des Balkans. His last published book is Là où se mêlent les eaux. Des Balkans au Caucase dans l’Europe des confins [Where the waters mix. From the Balkans to the Caucasus, at the edge of Europe] (with Laurent Geslin, La Découverte, Paris, 2018).

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- J.A. Dérens y Laurent Geslin: «Les Balkans, l’autre échec de l’Europe. Des frontières entre imaginaire et idéologie» en La Revue du Crieur No 3, 2017. ↩

- J.A. Dérens: «En Slovénie, la stratégie du choc», in Le Monde diplomatique, 3/2013. ↩

- The model of self-management owes a great deal to Slovenian Communist leader Edvard Kardelj, a close collaborator of Tito. See Jože Pirjevec: Tito, une vie, Éditions du CNRS, París, 2017. ↩

- J.A. Dérens: «Ballade en Yougonostalgie» en Le Monde diplomatique, 8/2011. ↩

- This pollution is less caused by industrial activities than by an aging second-hand fleet and the massive use of wood heating, following the frequent abandonment of public collective heating systems. ↩

- J.A. Dérens y L. Geslin: «La destruction programmée des dernières rivières sauvages d’Europe» en Mediapart, 15/8/2019 ↩

- J.A. Dérens: «Essor d’une gauche souverainiste au Kosovo» en Le Monde diplomatique, 12/2017. ↩

- J.A. Dérens y L. Geslin: «Ce exode qui dépeuple les Balkans» en Le Monde diplomatique, 6/2018. ↩

- Biepag: «The Western Balkans in Times of the Global Pandemic», informe de políticas, 4/2020. ↩

- J.A. Dérens y L. Geslin: «L’Albanie, bon élève à la dérive» en Le Monde diplomatique, 9/2020. ↩

- «Deklaracija organizacija civilnog društva ususret zagrebačkog eu Summita o Zapadnom Balkanu», disponible en https://www.cms.hr/hr/izgradnja-mira-u-hrvatskoj/deklaracija-organizacija-civilnog-drustva-ususret-zagrebackog-eu-summita-o-zapadnom-balkanu" target="_blank">https://www.cms.hr/hr/izgradnja-mira-u-hrvatskoj/deklaracija-organizacija-civilnog-drustva-ususret-zagrebackog-eu-summita-o-zapadnom-balkanu ↩