Ted Reese, author of the upcoming The End of Capitalism: The Thought of Henryk Grossman (Zero Books), argues for the continued relevance of Henryk Grossman’s theory of capitalist breakdown.

In 1929, Henryk Grossman, a Polish Jewish Marxist, published The Law of Accumulation and the Breakdown of the Capitalist System. This vital work did the best job after the deaths of Karl Marx in 1883 and Freidrich Engels in 1895 of defending and clarifying the real, revolutionary content of Marx’s Capital, which exposed capitalism as inherently crisis-prone and historically transient. With the leader of the reformist wing of European socialism, Karl Kautsky, having just declared that “it is no longer possible to maintain that the capitalist mode of production prepares its own downfall” and in fact stood, in the wake of World War I, “stronger than ever”,1 Grossman’s book – published just a few months before the infamous Wall Street Crash – anticipated a major crisis in the US that would ruin its European debtors.2

Despite having been proven right almost immediately by events on the New York stock exchange, The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown was met with almost universal hostility. Grossman’s disdainful critiques riled not only social-democratic reformists, who claimed capital accumulation could go on forever and without economic contractions; but also fellow communists – including Stalin’s leading economic advisor, Eugene Varga – who had produced confused theories of capitalist crisis. Both had failed miserably in their application of Marx’s methodological approach.

Grossman was accused of economic determinism; of having a ‘mechanical’ or ‘automatic’ theory of socialism’s succession of capitalism that ignored the importance of class struggle.3 Such accusations were obvious lies that replicated the very intellectual laziness Grossman had exposed. He had merely re-established the link between economic crisis and class struggle, showing that the former tended to stimulate the latter more than vice-versa.

Grossman was not concerned merely with periodic recessions, however, but the fact that accumulation became increasingly demanding and would eventually come up against historical limits, thereby compelling the working class to take up a world-historic struggle for a higher, stable, and sustainable mode of production. Because “it becomes more and more difficult to valorize [reproduce and expand] the enormously accumulated capital”4 as the system ages, capitalism must eventually enter an insurmountable crisis.

As a result of the confused theories produced by Marxists after Marx, and the refusal of the Soviet Union’s leading theoreticians to correct their errors by endorsing Grossman’s work – Varga repudiated it without bothering with any kind of scientific rigor – Grossman’s book remains extremely important and yet relatively unknown.

This is a big problem for communists seeking to defend Marx, whose work remains largely discredited in a world that saw off the threat of global revolution in the 20th century and returned to being almost universally capitalist. Because Marx’s epic tome has been so misrepresented and misinterpreted, often wilfully, The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown serves as a kind of sequel (as well as a very good primer) to Capital, highlighting and elaborating its most important findings at the same time as exposing the counter-revolutionary distortions that followed.

Marx’s methodology and crisis theory

Grossman lamented “a whole generation” of Marxists5 because “no one has proposed … any clear ideas, about Marx’s method of investigation”. Instead, the focus had been on interpreting Marx’s conclusions, which were “worthless divorced from an appreciation of the way in which they were established”.6

Grossman’s work subjected Marx’s method to a reconstruction “for the first time”, drawing out “the theory of breakdown” that “forms the cornerstone of the system of Marx”:

To be sure, Marx himself referred only to the breakdown and not to the theory of breakdown, just as he did not write about a theory of value or a theory of wages, but only developed the laws of value and of wages. So if we are entitled to speak of a Marxist theory of value or wages, we have as much right to speak of Marx’s theory of breakdown.7

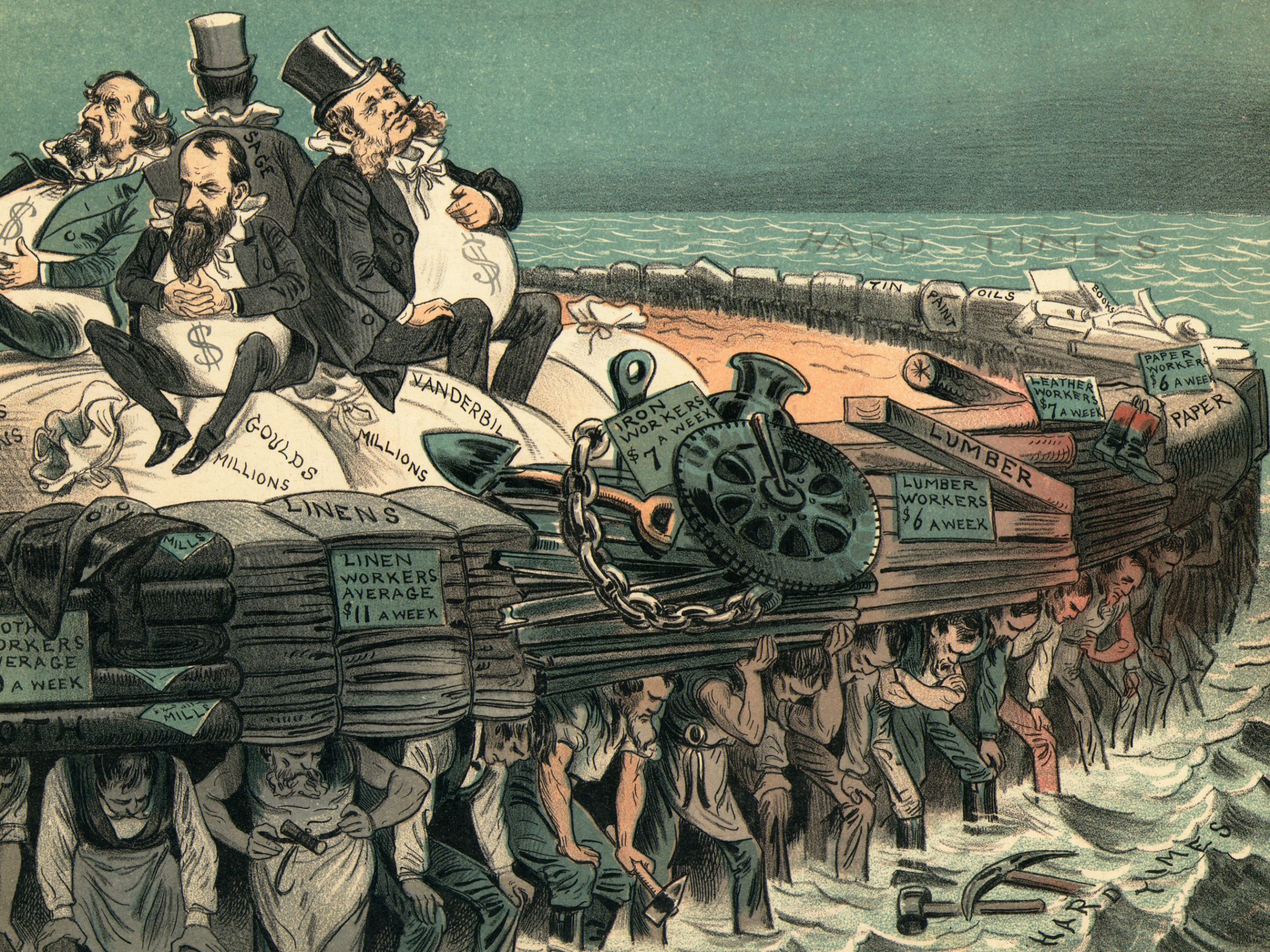

The reformist wing of the socialist movement either ‘corrected’ Marx’s breakdown theory or insisted that he never proposed one. They claimed instead that capital accumulated harmoniously and could do so ad infinitum, meaning the working class would always experience rising living standards under capitalism and only fight for socialism by peaceful, reformist means, and for moral, not economic, reasons.

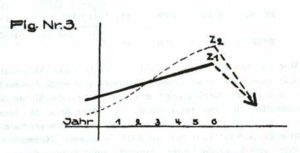

Capital’s ability to accumulate harmoniously had been ‘proven’ theoretically by Austrian social-democrat Otto Bauer in 1913. Using an abstract reproduction schema (mathematical pattern) of accumulating profit (and apportioning it to wages, capitalists’ consumption, and so on) similar to the ones employed by Marx – a simplified, ‘pure’ version of capitalism for the purpose of examining the essence of the system – Bauer claimed to have shown that capital could accumulate indefinitely in spite of a falling rate of profit.

Bauer, however, did this through only four cycles, or years. By continuing Bauer’s schema, without any alterations, Grossman found that by the 36th year the process broke down, exposing the reformist’s intellectual laziness. By this cycle of reproduction, capital ‘overaccumulates’ – becomes surplus – and cannot be reinvested. To do so would be pointless since it cannot yield a profit.

Alongside this surplus capital emerges surplus labor – the start of the schema assumes full employment – workers that capital can no longer afford to employ. To overcome overaccumulation, capitalists are compelled to reduce their outlay on wages, which eats into the profit available for accumulation and the consumption of capitalists. They are also compelled to innovate to raise the rate of productivity. More commodities must be made and sold and in less time than before to cheapen capital and generate enough profit to restore accumulation on a higher level. (The vitality of Grossman’s theory is thus clear when applied to today’s existential environmental crisis.)8

Grossman then does something that no other Marxist since Marx had done, and more thoroughly than Marx, in fact. He applies variations of the assumptions posited in the abstract schema – the constant value of wages and commodities, for example – and reintroduces, one by one, elements that had been initially omitted. At first, for example, only two classes existed, i.e. a singular capitalist class and the working class. Now competing capitalists and foreign trade are included, along with landlords and other middle strata. This brought the schema closer and closer to reality and tested the initial results as a means of verification. Did any of the variations or new factors help or hinder the breakdown tendency or suppress it altogether? Some things acted as counter-tendencies that delayed overaccumulation and breakdown, such as a relative or absolute reduction in wages; while others – ground rent paid to landlords eat into the profits of productive industrial capital, for example – had the opposite effect. Ultimately, Grossman found that no counter-tendency suppresses overaccumulation for good.

All of the other theorists, communist as well as social democrat, had taken their findings only from Marx’s abstract schema instead of reintroducing the factors that brought the initial abstraction closer and closer to reality – the scientific method of successive approximation. “Provisional conclusions were taken for final results,” says Grossman.9

They, therefore, produced a variety of ‘underconsumptionist’ and ‘disproportionality’ theories of crisis that could be put down to the external factor of economic mismanagement rather than any inherent systematic tendency. In the former, workers are not paid enough to buy all of the commodities they need, meaning profit goes unrealized. This could be solved through reform, by raising wages. In the latter, imbalances of commodities and profits between different departments of production, resulting in overproductions of goods that cannot be sold, demands centralized regulation, again making reform the answer.

A variation of underconsumption theory points to saturation of domestic consumption, making the solution the export of commodities to ‘non-capitalist’ foreign markets – an option that, in the analysis of Rosa Luxemburg, would become increasingly exhausted as the whole world became industrialized and capitalist. This version preserved an inherent breakdown tendency but, Grossman points out, shifted “the crucial problem of capitalism from the sphere of production to that of circulation [or consumption]”.10

The other theorists made the same mistake. Grossman showed that underconsumption, disproportionality, and overproduction were all symptoms of overaccumulation rather than the cause of crises. Without this proof, the communist movement has no justification for the economic necessity of socialism.

To prove that the cause stemmed from the mode of production, Grossman had to re-center Marx’s labor theory of value, the fact that the source of profit is capital’s exploitation of commodity-producing labor: i.e., that the capitalist appropriates part of the value created by labor, ‘surplus value’ (or surplus labor time) that is then realized through the sale of commodities. But because each crisis compels the capitalist to innovate and expand production, the number of exploitable workers tends to fall relative to the total amount of machinery/total capital employed. The very solution to crisis therefore later reproduces it on a greater scale, since the relatively diminishing productive workforce finds it harder and harder to create enough surplus value to further expand the ever-greater amount of total capital. This generally ever-growing underproduction of surplus-value is expressed by a tendency of the general rate of profit to fall. Debt and credit, a kind of ‘fictitious capital’, rises in their place.

Imperialism and war

Another thing Grossman deserves credit for is providing the clearest understanding of the imperatives behind imperialism and war, two of the most important counter-tendencies that prolong capitalism’s ability to rejuvenate at a higher level.

Capital exports – i.e. investment in production overseas, the export of technology/machinery and high-interest loans – are increasingly needed to expand and cheapen the exploitable workforce; and, at the same time, to provide an outlet for surplus capital that cannot be reinvested profitably ‘at home’.

Even Lenin’s revered pamphlet Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism comes in for stick from Grossman. Although “he makes many acute observations”, Lenin

“linked [the tendency of stagnation and decay] to the growth of monopolies. That there is such a connection is indisputable, but a mere statement is not enough. One is not dealing simply with the phenomena of stagnation… Imperialism is characterised by both stagnation and aggressiveness. These tendencies have to be explained in their unity… In fact both phenomena are ultimately rooted in the tendency towards breakdown… The growth of monopolisation is a means of enhancing profitability by raising prices and, in this sense, is only a surface appearance whose inner structure is insufficient valorisation.”11

Varga (who promoted a variation of underconsumption theory) denied the possibility of saturation of capital in any single country, simply saying that higher rates of exploitation were the attraction for capital exports. In a brave and devastating critique of Varga – given Varga’s closeness to Stalin – Grossman pointed out that this flatly contradicted Marx’s law of value:

[T]o suppose that capital can expand without limits is to suppose that surplus value can likewise expand without limits, and thus independently of the size of the working population. This [would mean] that surplus value does not depend on labour.12

Because profit rates tend to average out across branches or departments of industry on the world market (a higher rate falls to the average rate once the attraction of investment saturates and competitors catch up in terms of innovation), the commodities from the advanced country, with the higher level of technology, will be sold at prices of production higher than their value; and vice-versa. Such transfers, which Grossman called ‘unequal exchange’ (a term that became more commonly used in the 1970s), “become a matter of life and death for capitalism” as the expansion of capital becomes increasingly difficult and overaccumulation reaches new heights. This explains the increasing aggression of imperialist ‘foreign policy’ that we see today, especially by the US and Britain, the two traditional imperialist powers, in terms of sanctions, trade tariffs, and outright warmongering.

At the same time, competition on the world market intensifies – with a rising number of countries reaching a state of overaccumulation – meaning the imperialist powers are ever-more drawn into violent conflict with each other over resources that by right should be controlled by the nations in which they reside.

Kautsky – because he believed accumulation was harmonious – claimed that absolute capitalist breakdown would be brought about inevitably by world war, which in his view would happen only because of uncivilised ruling classes.13 On the other side of the same coin, Varga and Bukharin, a Bolshevik, believed WWII would bring about the completion of the world revolution. Grossman says:

It would be useless to search Bukharin for any other cause of the breakdown of capitalism than the ravages created by war…. If like Bukharin, we expect the breakdown of capitalism to flow from a second round of imperialist wars, then it is necessary to point out that wars are not peculiar to the imperialist stage of capitalism. They stem from the essence of capitalism as such, during all its stages, and have been a constant symptom of capital since its historical inception…. far from being a threat to capitalism, wars are a means of prolonging the existence of the capitalist system as a whole.14

Grossman was at pains to show that Kautsky’s was a subjective analysis and that the opposite was true: that massive overaccumulation brought about a systemic breakdown and world war followed necessarily because it was the only way to sufficiently devalue capital, to “ward off imminent collapse” and “create a breathing space” for accumulation to restart.15 War, because it is the ultimate means for devaluing capital and labor – and destroying the surplus of both – is therefore caused by and a temporary solution to the breakdown tendency.

Grossman cites the figure from Wladimir Woytinsky’s 1925 book The World In Numbers that “around 35% of the wealth of mankind was destroyed and squandered” in the four years of WWI; a war preceded by a worldwide long depression – like the one we’ve experienced since 2009 – and the US’s first national banking crisis in 1907. By the end of the war, says Grossman, the mass of living labour “confronted a reduced capital, and this created new scope for accumulation”.16

And yet it wasn’t enough – the 1929 Wall Street Crash followed. The New Deal attempted to resolve the crisis in the US and fascism attempted to resolve it in Germany (the equivalent of a New Deal in Germany through the Social Democratic Party reforms having already failed before 1929). Neither worked. It would take an even more destructive global war to end the depression.

Revolutionary conclusions

Ultimately, Grossman shows that all of the counter-tendencies must eventually exhaust themselves:

Despite the periodic interruptions that repeatedly defuse the tendency towards breakdown, the mechanism as a whole tends relentlessly towards its final end with the general process of accumulation. As the accumulation of capital grows absolutely, the valorisation of this expanded capital becomes progressively more difficult. Once these counter-tendencies are themselves defused or simply cease to operate, the breakdown tendency gains the upper hand and asserts itself in the absolute form as the final crisis.17

In the final chapter of his book, Grossman draws his conclusions: the breakdown tendency continually forces capitalists to attack the wages and conditions of the working class – and eventually becomes so strong that the latter is driven to revolution:

If the largest and most important force of production, human labour power, is thus excluded from the fruits of civilised progress, it is at the same time demonstrated that we are approaching ever closer the situation which Marx and [Friedrich] Engels already foresaw in the Communist Manifesto: ‘the bourgeoisie is unfit to rule because it is incompetent to assure an existence to its slaves within their slavery’. This is also the reason why wage-slaves must necessarily rise against the system of wage-slavery.18

Liberated from private property and the profit necessity, Grossman argued, production could be organized and planned on a social basis as a technical labor process, without any inherent causes of economic crises.19

Grossman was right

Grossman clearly stressed – and demonstrated – that working-class victories for higher wages and better conditions could deepen capitalist crisis; or bring forward the next one or even its final demise. He also agreed with Lenin that no crisis could be considered the final one before the working class had seized state power and implemented a higher mode of production.

This was ignored and Grossman was discredited as having a ‘mechanical’ theory of revolution that disregarded the importance of class struggle. Such obvious nonsense came from privileged reformists who had little interest in ending capitalism; and a Soviet leadership that had turned in desperation to a foreign policy of peaceful co-existence with imperialism in order to prioritize the survival of the Soviet Union over world revolution.

Despite cursing the Soviet leadership on both fronts, Grossman never withdrew his critical support for the Soviet Union and understood its economic and political problems in the context of imperialist aggression and isolation. Nevertheless, Grossman’s influence remains very limited as a result. Efforts to defend Marx’s crisis theory could have been strengthened if Grossman’s book had been endorsed by the Soviet leadership, which instead disseminated textbooks in the Eastern Bloc rejecting it. Even today, the movement has yet to address this issue. An abridged version – which does not include any of the final chapter,20 where Grossman talks most about class struggle – published by Pluto Press in 1992, remains the only English translation of Grossman’s book. Rick Kuhn, an Australian Marxist and author of a remarkable biography of Grossman,21 is working on putting this right. Kuhn’s translations of many of Grossman’s other contributions – most notably on revolutionary tactics, historical materialism, and the history of Marxism – have already begun to do so.22

Hopefully Kuhn’s translation will help to resolve the ongoing theoretical confusion within the communist movement at a time when we find ourselves entering capitalism’s deepest ever and probably final crisis23 – given that automation is now tending to replace the source of profit24 – without the correct Marxist economics having anywhere near the sort of influence that it should in the world. Grossman’s book has a large role to play in addressing such a tall order and – given that The Law of Accumulation is easier to read than and comprehensively counters the distortions made about Capital – is perhaps, in this sense, even more important than Capital itself.

- Henryk Grossman, The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System (Being also a Theory of Crisis) (Abridged), Pluto Press (1992), 54-5.

- Ibid, 197-8.

- See Rick Kuhn, “Economic Crisis and Socialist Revolution: Henryk Grossman’s Law of Accumulation, Its First Critics and His Responses”, Research in Political Economy 21 (2004), Amsterdam, 181-221.

- Grossman, op cit, 172.

- Ibid, 164.

- Ibid, 29.

- Ibid, 59.

- The capitalist production process is, as Grossman always stressed, a labor process and a valorization process. Because valorization depends on ever-greater labor exploitation, the labor intensity of mining and deforestation becomes increasingly necessary. Although these practices are usually now highly mechanized (resulting in their increasing unprofitability) the rate of exploitation of the remaining workers is very high. Just as surplus value is converted into capital quicker than it is produced, nature is converted into commodity capital quicker than it can be replenished. It is not simply capitalism’s ‘need for infinite growth on a planet of finite resources – as most leftists seem to put it – that gives rise to the central, immediate problem. Rather, it is the pace of expansion as determined by the ever-larger size of the total functioning capital and its need to expand still further, relative to nature’s ability to replenish itself – with our help or hindrance – combined with the need to create value based on labor exploitation, for the more non-renewable a material is, the more exploitation is involved in its reproduction. A socialist world, basing value creation on utility instead of exploitation, could therefore transition to production predominantly based on, for example, mycelium, hemp, and other fibrous plants. See Reese “The Green New Deal is species suicide – hemp, mycelium and nuclear are infinitely cleaner and greener than solar, wind and lithium”, grossmanite.medium.com, 12 March 2021.

- Ibid, 31.

- Ibid, 48.

- Ibid, 122.

- Ibid, 181.

- Ibid, p157-8: “When no such thing happened, [Kautsky went] on to deny the inevitability of the breakdown as such.”

- Ibid, p49-50.

- Ibid, p157.

- Quoted in ibid, p157.

- Ibid, p157.

- Kuhn, 2004, 193.

- Ibid, 195.

- For a summary of the final chapter of The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown, see Kuhn, 2004.

- See Kuhn, Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism, University of Illinois Press (2007), Illinois.

- See Grossman, Henryk Grossman Works vol I, edited by Rick Kuhn, Brill, 2017/

- See “Socialism is now an economic necessity, by Ted Reese”, 13 May 2020, Prolekult (patreon.com/prolekult).

- See Reese, “Automation represents the second, not fourth, industrial revolution. Just as the first necessitated capitalism, the second necessitates socialism”, grossmanite.medium.com, 7 April 2021.