The workplace is a complex system—something with too many variables to perfectly model and predict, that organizers must nonetheless try to navigate with imperfect data. To fully make sense of their surroundings, organizers need to understand the conflicting desires and influences of their co-workers, many of them hidden behind masks and contradictory premises. Every person swims in a sea of personal needs, formative experiences, and communal identities, suspended within the technical composition of production. Retail clerks exhausted with low wages but filled with hope by social movements, auto workers dabbling in both union reform and social conservatism, rideshare drivers loyal to the Democratic Party but emboldened through desire for workers control, all on winding and forked paths toward either decaying liberalism, rising fascism or a communist horizon.

The difficulty of accounting for complexity leads labor strategists to conjure practical half-truths, emphasizing specific possibilities or sites of struggle and downplaying others. Using case studies and direct experience as their sources, strategists may give primacy to the most militant or the most oppressed, to struggles against bureaucracy, liberalism or immiseration, to organic politicization or Marxist education. Strategies of this sort range from Kim Moody’s rank-and-file strategy[1] to the solidarity unionism of the Industrial Workers of the World.[2] While all of these approaches can have value under certain circumstances, it is exceedingly difficult for them to account for every variable in the workplace, requiring organizers on the ground to constantly reconsider and correct their approach.

In Class Consciousness and Communist Action, written for Partisan Magazine, Sean O calls for communists to examine how workers develop class consciousness through the struggle for control over the workplace, challenging the authority of the boss and asserting their humanity in the face of capitalist alienation. Sean O roots his ideas in both Marxist philosophy and his experience as a shop steward, witnessing workers awaken to their dehumanization and demand power and respect through everyday disputes with management. He then traces a thread from these mundane awakenings to the historic role of the proletariat as a revolutionary subject capable of ending capitalism.

While comrade O does an admirable job of synthesizing social practice and communist theory, he makes a number of sweeping assumptions about the development of class consciousness, and does not tie his strategy for workplace activity to a clear vision of socialist construction. This piece is both a critique of his limitations and an elaboration on his positive argument, meant to fill in some of the gaps left by his framework—namely a theory of class consciousness that can transcend conflict with individual employers and contend with the capitalist state, as well as a theory of socialist transition that can coordinate production across workplaces. This requires more than just workers in a given shop taking power from their own bosses. We need a communist strategy that can deal with the sheer complexity of capitalism and its interlocking aspects, which requires weaving shopfloor radicalism into something greater than itself.

Pedagogy of Revolution

Sean O asks where political struggle begins in working-class organization, versus where it is purely an economic dispute. Without communist intervention, he surmises that workers will tend toward economism, where their horizon is limited to negotiating over wages, benefits, and working conditions. Instead, communists should work with their coworkers to question the authority of management and assert their own control over production. We are in agreement over the limits of economism and the need for intervention, but his framework does not widen the scope of struggle beyond the workplace, which neither helps us develop communist consciousness or construct a socialist movement capable of transcending the worker-boss contradiction.

Comrade O ends without outlining how communists should advance forward from workplace activity, leaving the implications of his strategy up to interpretation—one could draw from him either a vision of decentralized self-management with each workforce taking over their place of work, or an unspoken political strategy building off of this shopfloor activity. He leaves open necessary strategic questions around what working-class militants should be fighting for—to live with dignity? To manage their own firms? To strengthen the position of workers in the nation? Or to take political power over every aspect of society, not just production?

He observes that workers have an impulse toward autonomy, leading even the most disorganized to engage in acts of protest and sabotage when they feel their humanity is being denied—for instance, a worker demanding their supervisor look them in the eye while talking to them. While he identifies this as a potential point for communists to intervene, he extends this concept further by claiming that “the worker’s desire to be a free human being leads in no direction other than that of communism, whether they recognize it or not.”

The phrase “whether they recognize it or not” hides a snake pit of contradictions. People of all classes are exposed to differing ideologies and formative moments, some imposed by the structure of capitalism and some incidental to their lives. These, alongside class, shape their consciousness, determining how they respond to new stimuli and adjust their ideas. While the experience of exploitation creates an opening for class consciousness, workers can draw a myriad of interpretations from each experience. These interpretations may be influenced by past experience, either their own or those they’ve heard secondhand, and by the conflicting interpretations of those around them, including those who speak for management and the state.

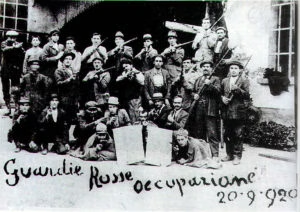

One worker may see asserting their dignity in terms of liberal egalitarianism, where everyone should learn to coexist and respect each other while maintaining the hierarchy they inhabit. Another might hold a populist outlook, with workers standing up as patriotic citizens against corporate power or foreign control. Many people will mix and match these ideas in ways that seem logical to them but incoherent to others. For instance, some Italian fascists fused revolutionary syndicalism[3] with nationalism, using class struggle as a weapon of the nation in its fight against international capital, rather than as a liberatory weapon for workers across borders. The national syndicalist Rossoni, influenced by the oppression he faced as an immigrant worker, wrote “we have seen our workers exploited and held in low regard not only by the capitalists but also by the revolutionary comrades of other countries. We, therefore, know from experience how internationalism is nothing but fiction and hypocrisy,” channeling the demand for workers to seize control of production into one for strengthening the power and prosperity of the nation.[4]

National syndicalism shares failings with reformist social democracy, in which socialists enter government in alliance with capitalists, advocating for workers to receive a larger share of profits within the capitalist system. Even when reformists themselves come from the working class and represent the workers' movement, they put themselves in a position where their power over the state can only be used to administer capitalism, disciplining the movement to the ruling class. National syndicalists achieved a similar result by radically different means, disciplining a genuinely transformative movement for self-management to the fascist state.

The gradients here are subtle, but necessary for us to incorporate into shopfloor strategy. When we assume challenging the boss can lead in no direction but communism, we leave ourselves open to cooptation. Communists play the role not just of organizer but of educator—synthesizing the direct experience of exploitation with the theory our comrades have developed through centuries of past experience. Just as we bring theory from past experience into new struggles, new struggles transform our understanding of Marxism and prepare us for those of the future. This does not mean that communists should practice didactic teaching, where the educator’s role is to fill the empty heads of their students with the correct ideas. Rather, we should use what Paulo Freire calls problem-posing education, where educators uncover themes in the lives of the oppressed and tackle them collaboratively:

Students, as they are increasingly posed with problems relating to themselves in the world and with the world, will feel increasingly challenged and obliged to respond to that challenge. Because they apprehend the challenge as interrelated to other problems within a total context, not as a theoretical question, the resulting comprehension tends to be increasingly critical and thus constantly less alienated. Their response to the challenge evokes new challenges, followed by new understandings; and gradually the students come to regard themselves as committed.[5]

In this framework, communist and non-communist workers are equals in developing new theories and plans of action. Communists put our political program in conversation with the experience of other workers, transforming all of our perspectives. Our role is to uncover new and broader themes in the struggle—actively tying the problem of disrespect from an individual manager into the system of capitalist management, and then into the international rule of the employing class. This allows us to integrate the specific experience of workers with the collective experience of the movement.

Socialists often mistake militancy for class consciousness. In this conception, communist agitation is synonymous with raising the militancy of rank-and-file workers, pushing them to greater levels of escalation until they’re ready to seize power from the boss and self-manage. Taken on its own, however, this approach will only lead to another form of economism—rather than petitioning management for the betterment of wages, benefits and working conditions, workers will determine their own wages, benefits and working conditions. This elides the role of struggles in the home and the neighborhood, and at the level of high politics, against oppression, imperialism, policing, and the undemocratic political order through which the capitalist class rules, and for the hegemony of the working-class in every facet of production, circulation, consumption, and political life. Trying to identify an isolated political role for shopfloor struggles is like the Greek myth of the hydra—for each head you cut off, another two sprout. We can only reach the communist implications of shopfloor activity through political activity that touches on every face of the ruling class, which means challenging the capitalist hydra in its heart, not just whichever head is tasked with running a given workplace.

In order to develop a fully realized communist strategy for the 21st century, we need to nest shopfloor strategy within a wider vision of working-class organization. Communism is not just an accumulation of single-issue campaigns and local seizures of power, but the movement of the entire working-class, capable of solving universal problems like the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and combining forces against particular ones like patriarchy, white supremacy and workplace management. This includes those outside stereotypic definitions of worker, like prisoners, unpaid domestic laborers, the unemployed, and those jumping from gig to gig. By overemphasizing the direct experience of workplace oppression, we risk ignoring those outside traditional employment, or who might see their most immediate enemy as the police, real estate developers, environmental polluters, etc.

When communists disperse into issue-based campaigns, we need to guard against the creation of separate fiefdoms of struggle. For instance, assembly line workers over production, environmentalists over nature, tenants over housing, etc. Communists must bring their specialized expertise back to the movement for universal emancipation. On the shop floor, our responsibility is to push the struggle further, beyond the workplace, challenging the entire political apparatus of the ruling class, not just those tasked with directly managing workers.

To reach the political conclusion of class struggle, communists have a responsibility to help workers synthesize ideas and push against liberal and reactionary conclusions. This can feel exceedingly difficult precisely because it doesn’t always flow naturally from labor-management relations. Sometimes it will require introducing new elements that might seem unrelated, like the influence of employers on labor law, or the role of gender and race under capitalism. Chaining these themes together both strengthens the struggle and elevates it beyond the shop floor. This means communists must use the day-to-day realities of working-class life to scaffold higher levels of theory.

Other times shopfloor struggle will begin to spill out of the factory, the warehouse or the retail outlet, allowing communists in the right time and place to intervene in a struggle that, out of necessity, begins to politicize itself. For example, in the Gas Protest of 1974, where rising tensions between striking miners and state police, dovetailed with the historic memory of miner insurgency, forced the state of West Virginia to end gas rationing.[6] Another instance is the Watsonville Canning Strike of 1986, where immigrant strikers and socialist activists transformed a walkout over pay and benefits into a popular expression of the Chicano Movement.[7] In the former case, economic protest spilled out of the shopfloor and challenged the state itself. In the latter, organizers actively drew a wider movement into the strike. Both were opportunities for communists to scaffold different levels of struggle, helping striking workers develop the political acumen necessary to construct socialism.

This is not to say that power struggles within the workplace are a waste of time. However, communists who see them as naturally blossoming into a conquest of power will end up missing opportunities to uplift and expand their implications. Rather than a full curriculum in class conflict, shopfloor activity is an object-lesson that can be used to raise and discuss political questions from which workers can draw a variety of conclusions based on the material possibilities in front of them.

When communist militants elide these questions from our workplace strategies, we risk miseducating our comrades about the potential of shopfloor skirmishes and the necessary steps to push them further. In order to forge a new revolutionary consciousness among workers, we need to incorporate both the advantages and limitations of industrial movements and to help each other see the bigger picture.

From Labor Strategy to Revolutionary Strategy

Sean O states that the “potentiality of communism does not emerge from outside of the working class.” While this is correct in a structural sense, we need to be clear that the scientific formulae workers can use to construct socialism cannot all be found through workplace action. The notion of communist theory coming from inside or outside the extant working class fails to describe the relationship between the socialist and workers movements, simplifying our role into teasing out the inherent communism of working-class self-activity. Communist theory is drawn from the entire history of the workers' movement, meaning that what appears to be an intervention from outside can be a lesson drawn from centuries of direct experience, passed down through the socialist milieu and returned again to its home in the workers' movement. This is especially important when the consciousness of the working class is low, forcing us to look to past, more revolutionary incarnations of the movement for data.

Sean O cites the factory councils of Turin as an example of a successful challenge to managerial authority. The factory councils, however, never developed the political direction and leadership to expand beyond industrial occupation, and the socialist movement failed to intervene and empower them further, leading them to fade away in the wake of fascist reaction.[8] On the other hand, the factory committees and soviets of the Russian Revolution, which preceded the Turin movement, did succeed in effecting a revolutionary transfer of power, primarily but not exclusively under Bolshevik leadership. In the course of the revolution, they were subject to a complicated exchange between the political parties who intervened in them, the needs of different class strata, and the demands of the Russian Civil War. When committees first began to take control of production, it was primarily out of a desire to increase defense production for the First World War, combined with the democratic aspirations of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries. For defensists, workers' control was a means for transforming Russia into a liberal-democratic power, with the question of socialism tabled till the distant future.

After the October Revolution, some Bolsheviks in the factory committees began to argue for workers' self-management in tandem with central planning. However, the devastation of the Russian Civil War destroyed the industrial base for the committees and pushed the Bolsheviks to reintroduce labor discipline, cutting short their experiment.[9] We could speculate that under better conditions the factory committees might have found a path to both survival and workers' control, but they would have to do so in alliance with the Red Army, the peasantry, and workers outside manufacturing. The point is not that communists should put more or less emphasis on planning over autonomy, but that workers' control does not always lead to communism—and that even when it does, communists must actively win support for our program.

Setting up an inside-outside dichotomy creates an awkward model where socialist ideas must flow from organic activity in the present, but where we can’t reapply lessons drawn from past activity. We develop richer theory and strategy when we put the different spheres of communist work in conversation. Do our coworkers see their struggle against management reflected in those against landlords, police, and politicians? Do they see these conflicts as sharing a common solution? What form will that solution take, and how should we coordinate it? Shopfloor struggle alone cannot end class society and social domination, and for masses of workers to develop a communist consciousness we need to carry out a strategy that addresses all aspects of capitalist society.

Communism is a totalizing framework, requiring us to consider the workplace as one node in a complex system that the working class needs to coordinate in its entirety. This is what political power means: governance of the whole of society. This requires being able to manage production, logistics and outputs like food, housing, and healthcare as a cohesive and interconnected project. To meet the needs of the entire populace, we need to make central decisions; a factory council in charge of producing wheat, for instance, cannot be allowed to produce too little for the supply of bread to match the needs of society. We should be clear that comrade O does not advocate explicitly for this kind of radical decentralization. However, communist strategists have a responsibility to consider these questions and incorporate them into their blueprints, or else our political opponents may channel the consciousness forged in economic struggle into avenues inimical to communism.

Science on the Shopfloor

We have opened multiple questions on revolutionary strategy and the workplace—the differing facets of class consciousness, the relationship between economic and political power, and the tension between coordination and autonomy of production. While the sections above take steps toward addressing these questions, we should not pretend to have resolved them. While we have decades of data from past movements to draw from, we should be wary of drawing from existent models uncritically. Past communists built reform caucuses, study circles, strike committees, dual unions, bureaucratic cliques, and a host of other interventions aimed at developing a revolutionary workers movement through shopfloor activity. All of them were synthesizing political principles and the practical needs of the moment, with varying levels of success. While we can look to historical narratives for case studies and inspiration, labor strategy remains a scientific problem for us to solve.

To this end, we will conclude with an open question for study and reflection, the answers to which we may find through observation and debate: What structures should we use to facilitate political agitation and development on the shop floor?

Most modern socialists in the labor movement, more or less following Moody’s rank-and-file strategy, operate through transitional organizations, bodies meant to raise the general consciousness of workers through militant but non-revolutionary transitional demands—for instance, Teamsters for a Democratic Union, which aims to democratize the Teamsters and put them under rank-and-file leadership, and Labor Notes, a journal which serves as a hub for union militants.[1] These organizations are usually formed by socialists toward socialist ends, but define themselves through their broader basis of unity, aiming to instill a class consciousness more amenable to socialism by virtue of its militancy and critical analysis of those in power.

Reflecting on the brief and efficient history of Labor Notes, Marxist and labor journalist Kim Moody wrote that “when choices had to be made between educating in practical strategies and actions, on the one hand, and advanced political education or mere propaganda, on the other, for better or worse we almost invariably chose the former. That was the right choice and part of what made the project work as well as it did.”[10] Moody’s assessment highlights both the project’s strength and its limits. Labor Notes promotes a pragmatic approach to workplace organizing, with its finger close to the pulse of capital. By recognizing and responding to class struggle in motion, from wildcat strikes to sophisticated union-busting schemes, Labor Notes was able to develop a base of union militants in need of down-to-earth, immediately useful analysis that could be applied to workplace activity.

Their structure for organizing conversations, for instance, is a stock training material for new labor organizers, aimed at discerning workplace issues, stoking anger around them, laying the blame on management, and finally coming to a collective solution—unionism. Organizers enter with open-ended questions and aim for the other conversant to walk away with a concrete task for the union: inviting a coworker to a meeting, composing a list of grievances, convincing their department to sign on to a demand letter, etc.

Transitional projects, however, generally measure their success via their transitional goals, not their implicit socialist purpose. This creates friction between vision and practice rather than merging the two, with trade unionism eclipsing revolutionary politics. Though the organizers behind projects like TDU and LN did initially link them with political education, their political organizations have largely faded while their transitional projects have remained resilient.[11] Explicitly socialist and communist union caucuses, study circles, and labor journals are close to nonexistent in the contemporary labor movement.

There is also the issue of whether transitional demands are effective at raising consciousness, let alone whether we can leverage them toward revolutionary politics. Those with direct experience of transitional organizing are best positioned to summarize and assess its success and benefit the entire movement with their findings. Unfortunately, many contemporary treatments of rank-and-file strategy, such as sociologist Barry Eidlin’s What is the Rank-and-File Strategy, focus on the achievement of transitional demands, while downplaying the development of socialist consciousness and dismissing those who “propagandize” for socialist politics.[12] In order to fully grasp the best routes toward communist politicization, we need to evaluate the success of transitional organizations and experiment with new structures for agitation.

Sean O makes a compelling case for the role of shopfloor activity in this process, but we need to go further to generate mass communist politics and build a fighting party. We do the working-class a disservice when we develop labor strategy while leaving revolutionary strategy unspoken. Power over production can be a tool for workers to learn the willingness and expertise to govern, but only as part of a wider pedagogy of revolution. The responsibility of communists is not to simply push everyday struggles further, but to integrate them into the entire process of liberation. To accomplish this, our task is to draw the mass of workers in as co-researchers studying the construction of communism. When workers are ready to unite across sectors and movements, we will be able to strike the capitalist hydra in its heart.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Moody, Kim. “The Rank and File Strategy: Building a Socialist Movement in the U.S.” Solidarity, 2006. https://solidarity-us.org/rankandfilestrategy/. ↩

- White, Don. “Solidarity Unionism: What It Is and What It Isn't.” organizing.work, September 6, 2018. https://organizing.work/2018/09/solidarity-unionism-what-it-is-and-what-it-isnt/. ↩

- An ideology advocating for control of production to transfer from managers to workers directly via labor unions. ↩

- Roberts, David D. In Syndicalist Tradition and Italian Fascism, 108. University Of North Carolina Press, 1979. ↩

- Freire, Paulo. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 81. Continuum, 1970. ↩

- Ely, Mike. Ambush at Keystone No. 1. Kasama Project, 2009. ↩

- Shapiro, Peter. “The Necessity of Organization: The League of Revolutionary Struggle and the Watsonville Canning Strike.” Viewpoint Magazine, August 30, 2018. https://viewpointmag.com/2018/08/30/the-necessity-of-organization-the-league-of-revolutionary-struggle-and-the-watsonville-canning-strike/. ↩

- Azzellini, Dario, Immanuel Ness, and Pietro Di Paola. “Factory Councils in Turin, 1919–1920.” Essay. In Ours to Master and to Own: Workers' Control from the Commune to the Present, 130–47. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011. ↩

- Smith, S. A. Essay. In Red Petrograd: Revolution in the Factories, 1917-1918, 258–65. Cambridge University Press, 1983. ↩

- Moody, Kim. “The Rank and File's Paper of Record.” Jacobin, November 8, 2016. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/08/labor-notes-rank-and-file-reform-unions-concessions-labor/ ↩

- Moody, Kim. “The Rank & File Strategy and the New Socialist Movement.” Spectre Journal, December 20, 2020. https://spectrejournal.com/the-rank-file-strategy-and-the-new-socialist-movement/. ↩

- Eidlin, Barry. “What Is the Rank-and-File Strategy, and Why Does It Matter?” Jacobin, March 26, 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/03/rank-and-file-strategy-union-organizing. ↩