Read by Will

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic seemingly came out of nowhere. As the pandemic spread across China and made its way to Europe, Americans laughed at the prospect of the virus reaching our shores. In an age where contagions are contained so well that a significant portion of the American population questions the efficacy of vaccines (because the vaccines have so thoroughly contained epidemics that the epidemics have left the public memory) the idea that a plague of this nature could be real, and could affect us, was not believable. Yet this is not the first time that this has happened. In 1981, a similar phenomenon occurred: AIDS was discovered. And just like Covid-19, it first appeared in a population that America had largely deemed subhuman. In the case of AIDS, this was the gay community; in the case of coronavirus, this was China. This cognitive dissonance, the idea that the same pandemic that was ravaging this ‘other’ community could not touch Americans-- or at least, in the case of AIDS, heterosexual Americans-- led to a deadly and terrible delay in responding to the pandemics. Despite the similarities, even to the point of Anthony Fauci leading the governmental response against the pandemics, AIDS has largely been ignored during the corona-crisis, probably because of the ‘gentrification of the mind’, to borrow a phrase from AIDS scholar Sarah Schulman, that occurred after the AIDS crisis ‘ended’ in 1996.

So what is AIDS and where did it come from? AIDS, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, is a condition caused by HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus. This virus slowly weakens the body’s immune system, leaving it susceptible to diseases and opportunistic infections that a healthy immune system would have no problem staving off. AIDS has been traced back to the Congo, where it is thought to have crossed over from primates to humans, most likely in the early 20th century. While AIDS was not medically known until 1981, recent studies have shown it in Kinshasa in the 1920s, and in nearby towns as early as 1937.[1] This begs the question of why it took more than 40 years, from 1937 to 1981, for AIDS to be noticed, and why it was first identified in the United States, rather than the Congo where it originated.

From 1908 until 1960, the Congo was a Belgian colony, and the official language, imported from Belgium, was French. This colonization kept the Congo relatively underdeveloped as a whole, but a process of combined and uneven development did occur. While agriculture remained very inefficient compared to Western standards, certain sectors of production and, importantly, transportation, were at very high levels. The Belgians built miles and miles of railroads in the Congo to better assist their imperial plunder of the land’s natural resources. These same railroads, and the military personnel who staffed them, would help spread HIV/AIDS throughout the country.

In 1960, the left-nationalist leader Patrice Lumumba declared independence and became the first Prime Minister of the nation. This early act of decolonization was bitterly resisted by the Belgians and the imperialist powers generally. Lumumba was quickly overthrown and assassinated in a CIA-backed coup in January 1961, and a five-year civil war ensued. In the aftermath of the Congolese civil war, there was a dire shortage of technical personnel and medical professionals in the country. There was a clear need to import healthcare workers from other countries, but there were disputes within the country and within the UN as to which country should send personnel. It was ultimately decided that the personnel should be sent from Haiti, as it was the only nation that spoke French and was black and independent. When these Haitian professionals returned to Haiti, AIDS most likely entered the Western hemisphere for the first time.

The country they returned to was the poorest in the Western hemisphere, and was still a neo-colony of the United States. Since Haiti declared its independence, the United States had, at various times, militarily occupied the island, overthrown its leaders, propped up dictators, and dominated its industry. Crucially, in the late 1960s, when these professionals returned, the United States’ blood bank industry was beginning to make inroads into Haiti. Following a tightening of industry regulations after a hepatitis outbreak in 1968[2] that was tied to blood transfusions, the industry had become monopolized as the smaller companies could no longer afford to abide by the regulations. Once the blood banks had reached monopoly status, they faced two problems. First, they needed more supply to meet the demand for blood (and its byproduct plasma); despite being one of the only industrialized nations to pay for blood donations, and despite intentionally targeting the poorest and most desperate in society (in one instance paying donees with coupons to liquor stores[3]), the companies were not able to find enough blood domestically, and needed to expand overseas to fill in this gap. The other problem that the monopolies faced was that of growth; they had already captured the American market, and the only options for continued growth were to either increase how much they charged, or cut back on their costs. The solution to both of these problems was the imperialist exploitation of Latin America. The banks would be able to pay less for blood in these countries, while also remaining close enough to the United States to reduce shipping and transportation costs. Importantly, a blood bank was opened in Haiti. The lower cost of production in Haiti was combined with a population desperate for jobs, and struggling to survive. The blood banks were ecstatic; they were also unknowingly bringing AIDS back to America.

This extraction of blood from Haiti and its subsequent shipment to the United States helped spread HIV/AIDS, putting anyone who required a blood transfusion at risk. This is important for a number of reasons, but one of the primary ones is to understand that pandemics do not occur outside of a social context. The capitalist world system that HIV/AIDS arose in cannot be separated from the pandemic itself. The economic domination by monopolies, and their need to extract from the ex-colonial countries in order to sell in the imperialist countries[4], helped spread HIV/AIDS worldwide. Capitalism’s need to put profit before lives furthered this spread, both by skirting safety regulations and by ignoring the prevalence of AIDS in the Congo[5] until significantly after the pandemic had spread to America. Pointing out the origins of AIDS is not to say that the solution would have been isolation, or a reversion toward autarky, preventing anything from spreading from other continents to America. Rather, it is to demonstrate how capitalism’s global economic system but narrow national interests create the perfect breeding ground for pandemics. We will see later how this narrow nationalism continued even once the crisis was well known. With that, we can turn toward the story of AIDS in America.

We know for a fact that AIDS was in the United States in the 1970s, and spreading; it has been suggested that it may have seen its first death in America as early as 1969. These did not cause mass outbreaks, to our knowledge at least. Partly, this is because there is a delay between the contraction of HIV and the outbreak of symptoms; in some cases, this can be as long as ten years. The most important factor, though, is the fact that AIDS can only be contracted via exchange of blood or sexual fluids. It cannot be contracted through casual contact. Thus for AIDS to spread rapidly, it required a group of infected people to have an exchange of blood or sexual fluids with a frequently changing group of uninfected people; a person with AIDS in a monogamous relationship would most likely only spread the virus to their partner, and an injection drug user who did not share needles would most likely not spread the virus to other injection drug users. If it was a lesbian relationship, the risk of infection was extremely low as well.

It was for these reasons, and not any divine retribution or punishment for ‘immorality,’ that the gay community in the United States began to become infected with HIV/AIDS. Following the Stonewall Riot in 1969 (the same year that America saw its first AIDS death) and the emergence of the gay pride movement, gay men began to see sexuality as a form of liberation. After centuries of oppression, and particularly after the McCarthyist repression of homosexuality, gay men who left the closet wholeheartedly embraced their sexuality. They began to revel in this newfound freedom. The sexual revolution of the time had its impact as well; having frequent, largely anonymous sex, was seen as a liberatory experience. Gay bathhouses emerged for just this purpose. Monogamy was shunned and associated with heteronormativity-- it was seen as trying to ‘fit in’ to a society that did not accept gay men for who they were. There is nothing inherently wrong with sexual freedom, and many gay men recall the fun that they had at the time. However, the risk of contracting an STI in this situation was enormous. Many proudly took doses of penicillin and other medications that their doctors prescribed them and continued to go to the bathhouses. Yet penicillin was no match for HIV.

The Early Years of AIDS

AIDS first appeared as a distinct illness in the summer of 1981, when the New York Times ran an article entitled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” This article highlighted an outbreak of Kaposi’s Sarcoma in young, gay men in San Francisco and New York. Typically, Kaposi’s Sarcoma affected less than 6 people per million cancer diagnoses in America, but in equatorial Africa this rate increased to 9 percent of all cancer diagnoses. Kaposi’s Sarcoma outbreaks were the first sign of the international flow of AIDS. The average age of the gay men being diagnosed was also more than a decade younger than typical diagnoses in the United States. At the same time, California’s gay community began to see its first outbreak of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), a pneumonia so rare that the only known prophylaxis, which halved mortality rates, was no longer produced, and the limited supply was locked away by the CDC. Doctors who needed the prophylaxis had to specially request an overnight shipment. Despite this, the New York Times and the mainstream media, even most of the alternative media, ignored the burgeoning epidemic until, and even after, it became unavoidable.

Medical personnel initially referred to this new disease as “Gay Related Immune Deficiency” (GRID), but by late 1982 the terminology had changed to “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome” (AIDS), as injection drug users, hemophiliacs, and Haitian immigrants began to come down with PCP. It had become clear that AIDS was not inherently tied to homosexuality, but was an infectious disease that was somehow being spread throughout the United States. Still, most of the infected were in the gay community. And the gay community was largely unaware of this emerging crisis.

One of the few people paying attention, however, was Larry Kramer, a gay playwright who had fallen out of favor with other gay men after his 1978 novel Faggots lambasted the promiscuity and drug use of the time. Despite this, in June of 1982 Kramer was able to organize a meeting in his apartment of others who were concerned about the growth of GRID (soon to be AIDS). What emerged was the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), the first organization in the United States founded to deal with the AIDS crisis. GMHC helped care for the afflicted, set up wills, distributed information, and even ran an informational hotline. From the start, though, GMHC was rife with conflict, with Kramer pushing for a more combative approach.

By 1983, he had left the organization. Upon leaving, he authored a now famous essay in the New York Native (a gay newspaper) entitled “1,112 and Counting.” Kramer’s essay began:

If this article doesn't scare the shit out of you, we're in real trouble. If this article doesn't rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get.[6]

At the time, this seemed largely hyperbolic. Lester Kinsolving, the only member of the White House press corps to ask about AIDS, was routinely laughed off when he would bring up the crisis, with his sexuality brought into question. The press was clearly not taking the crisis seriously, and proportional to both the gay community and the United States at large, not that many people had died. The lack of testing for AIDS allowed people to be willfully ignorant of the emerging crisis, wishing it away as it exponentially spread across the country. Kramer’s reputation as a sexual conservative was also part of the reason that his call for urgency and attention were ignored. His writing was viewed as the continued ramblings of a puritanical playwright out of touch with the community, rather than the dire warning that it was. It would be years before Kramer found an organization that shared his urgency.

1983 did see some positive steps in the anti-AIDS movement. In June of that year, the Fifth Annual Gay and Lesbian Health Conference was held in Denver, CO. At the conference, a group of a dozen AIDS activists asked to speak, rather than just having their health talked about. This group, including the late Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, presented what came to be known as the Denver Principles, a document that they had drafted in their hotel room. The document was split into four sections: the first three were recommendations for, respectively, health care professionals, all people, and People with AIDs. The final section was entitled “Rights of People with AIDS.” The points in the document ranged from calls for solidarity to equal rights and medical care. The most important part, however, was the fact that the Denver Principles called for People With AIDS to be involved in every aspect of their own care, to the point of refusing treatments that they did not deem effective. The self-empowerment of the Denver Principles would be a core aspect of the anti-AIDS movement going forward, and especially of ACT UP, the most effective and prominent group in the fight against AIDS.

The Denver Principles, like Kramer’s essay, would set the tone for the future emergence of ACT UP. But ACT UP did not emerge until 1987, and in the meantime various AIDS groups popped up throughout the country to provide care for people living with AIDS and advocate for them. GMHC continued to grow, and in San Francisco, the Shanti Project, originally founded to help people with any life-threatening illness, began to focus almost exclusively on providing for those with AIDS. There is no question that these groups provided valuable services, but Kramer had penned his essay for a reason. Simply trying to alleviate the pain of the afflicted was not enough. A cure was desperately needed, Reagan’s federal government was doing next to nothing, and the religious right was arguing that gay people deserved to have AIDS. Pat Buchanan argued in 1984 that “The poor homosexuals — they have declared war upon nature, and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.” One year later, he was appointed as Reagan’s Communications Director. Reagan himself would not even say the word AIDS until 1987.

At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry was ignoring the crisis altogether. L. Patrick Gage, the vice president for exploratory research at Hoffman-Laroche (a major pharmaceutical company at the time), was quoted in 1985 as saying,“This will sound awful, but you have to understand that a million people isn't a market that's exciting. Sure, it's growing, but it's not an asthma or a rheumatoid arthritis.”[7] Even the death from AIDS of Rock Hudson, a macho movie star who was closeted until just before his death, was not enough to seriously engage the pharmaceutical industry or Reagan’s government. Nothing seemed capable of moving the fight against AIDS forward. This changed almost overnight after Larry Kramer was asked at the last minute to fill in for a speech at the Lesbian & Gay Community Services Center in March of 1987.

ACT UP FIGHT BACK 1987-1991

Larry Kramer’s speech began where his ‘1,112 and Counting’ essay had left off:

If my speech tonight doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in trouble…I sometimes think we have a death wish. I think we must want to die. I have never been able to understand why we have sat back and let ourselves literally be knocked off man by man without fighting back. I have heard of denial, but this is more than denial—it is a death wish.[8]

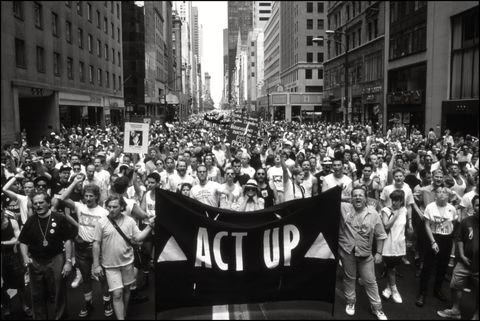

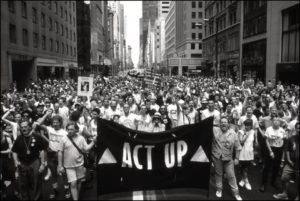

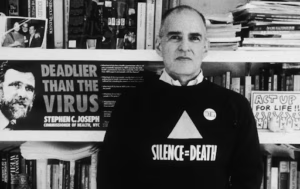

When Kramer closed his speech by asking the attendees who would join him in founding a new organization, nearly every hand was raised. At the next meeting, the group agreed that they needed to more directly confront the organizations and institutions that had the power and resources to combat AIDS. The meeting after that, the group officially chose a name: the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP. Before going into the history of ACT UP, it is worth briefly discussing what ACT UP was in its heyday.[9] This will largely be confined to ACT UP New York (ACT UP/NY), the original and largest chapter that generally set the tone for the other national sections. ACT UP defined itself as a “diverse, nonpartisan group of individuals united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis”; every Monday night meeting began with this statement, as well as a request for any cops in attendance to reveal themselves. It had no elected or permanent leadership, and those in charge of organizing the agendas for the Monday meetings were drawn from the various committees (housing, treatment and data, majority actions etc.) and were rotated frequently. The organization had no official membership or dues; anyone could vote after attending a couple of meetings, and meetings were open to anyone. The organization did not have an official publication, but in 1989 Outweek was started as a weekly publication and was unofficially referred to as ACT UP’s Pravda.

At its founding ACT UP largely reflected the demographics of AIDS at that time: young, white, gay men. Many were working class, but as tends to happen with activist organizations, those who rose to leadership and the media gave the most attention to were petty-bourgeois or even outright bourgeois: Peter Staley, one of main spokespeople for the organization, worked on Wall Street.

ACT UP’s initial action in March of 1987 was to shut down Wall Street in protest of the exorbitant price being charged for AZT, the first drug approved for AIDS. AZT was priced at $10,000 per year because the company knew that people with AIDS had no choice but to buy their drugs; after the protest, the company brought the price down to $8,000, still the most expensive drug ever at that point.

This structural lack of access to potentially life-saving drugs was not only caused by the privatized, profit-driven pharmaceutical industry. Anthony Fauci, the current liberal hero who has mishandled the coronavirus pandemic and bent science to the needs of corporations, was himself one of the largest barriers to getting ‘drugs into bodies.’ In particular, his lack of action on the PCP crisis among people with AIDS led to tens of thousands of premature deaths. As mentioned earlier, PCP is an extremely rare form of pneumonia (to the point that many doctors, especially before the internet, did not know about its prophylaxis). It was also one of the earliest signs of the AIDS crisis, as well as evidence that AIDS was passed via blood after a baby that required a blood transfusion developed PCP in 1982. The blood from the transfusion was eventually traced back to an HIV-positive man.

Early in the epidemic, nearly 3 out of every 4 deaths from people with AIDS were from PCP. Clearly, in the immediate term, controlling PCP outbreaks was the most important way of prolonging the lives of people with AIDS. Despite this, Fauci, as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (the branch of the NIH that was in charge of the AIDS crisis), required participants in any AIDS-drug trials stop all other medication, including prophylaxis for PCP. This was one of many reasons that NIAID failed to fill nearly all of their trails.

Beyond this, Fauci passionately refused to send notices to doctors nationwide about the prophylaxis for PCP, claiming that “there’s no data.” The data did exist that the prophylaxis was effective; however, it had not been tested on people with AIDS. Importantly, Fauci was also neglecting to conduct any of these studies on people with AIDS. His claim that there was no data rested on the assumption that AIDS, a retrovirus, suppressed the immune-system differently than chemotherapy, and that gay people might be biologically different from straight people:

There were published studies showing that Bactrim (the prophylaxis for PCP) prevented PCP in cancer and transplant patients, both infants and adults. There was no evidence suggesting gay people were biologically different from straight people, or that immune suppresion caused by a retrovirus was different from immune suppression caused by chemotherapy. While anecdotal evidence was not data per se, it suggested that using prophylaxis was just as safe and effective. Because the practice was commonplace among New York doctors, death rates from PCP were the lowest of any city in the plague-riddle country.Fauci did not budge.[10]

This was not the only instance of Fauci’s negligence with regard to AIDS. Another opportunistic infection that was ravaging people with AIDS was cytomegalovirus, which was causing blindness. At the time, Ganciclovir, an anti-blindness drug commonly known as DHPG, “was lost in a negative feedback loop”, to quote David France. In spite of ACT UP protests and pressure, “the FDA refused to give it a full release without a clinical trial, something Fauci’s NIAID refused to undertake.” As a result, activists were forced to rely on hearsay and anecdotes to find promising drugs.[11] Bill Bahlman, an anti-AIDS activist, made clear in a private dinner with Fauci that there was a compassionate use program that had allowed over 2,500 people to use DHPG without FDA approval. Surely this was a large enough sample size to tell if the drug worked by retroactively going through the notes that doctors kept on their patients. But to Fauci, “the data isn’t worth a shit! Because you have to do a study to get the data. That’s the problem.”[12] In the mind of a thoughtless bureaucrat like Fauci, only a pure study on a very specific drug for a very specific group of people could ever be ‘worth a shit.’ There could be no critical thought, no creative ways of attempting to speed up the bureaucratic processes that were causing unnecessary blindness and death. Fauci simultaneously argued that underground AIDS drugs should not be given on a compassionate basis (without FDA approval), even in the case of anti-blindness drugs to stop the blindness that was becoming prevalent, while also arguing that it was too difficult to do studies on all these drugs to actually test their efficacy. Essentially, he was against giving the drugs without FDA approval, and against pursuing avenues to try to get them approved by the FDA, effectively shutting down the drugs even as possible solutions, at least legally.[13]

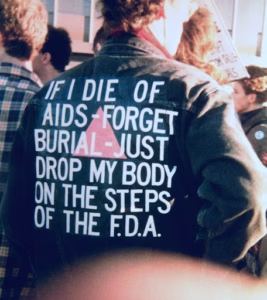

While Fauci used the FDA as a crutch to avoid any effort to actually combat the crisis, ACT UP began to look at which specific institutions could help solve the crisis. As Gregg Bordowitz, who came up with the idea to ‘Seize Control of the FDA’ recalls, “Millions of groups...have...protested in front of the White House....[W]e need to go to the Food and Drug Administration....This is an institution that is very specific to the issues that we’re facing.”[14] The intention was not just to expose the FDA as the barrier that it was (anti-AIDS medication was not expedited--it went through the same years-long process that allergy medicine did). Rather, Bordowitz had a much larger vision of what the action was about. He “had a kind of fantasy about what kind of activist language it should be. So I had come up with this slogan, ‘Seize Control of the FDA.’ That was frightening to many people, this notion of seizing control. But I was very insistent...People with AIDS are going to take over the agency and run it in our own interests.”[15]

This action was different from other ACT UP actions, in that national ACT UP’s were consulted and recruited to participate, with the umbrella group ACT NOW being formed to coordinate this. Further, there was intense education of the membership going into the action:

The entire body of ACT UP was schooled in advance with knowledge of complicated issues that until then had largely remained in the province of Treatment and Data Committee members. The latter, who had been studying treatment issues for over a year and had also profited from knowledge garnered by AIDS activists in other U.S. cities, prepared an FDA ACTION HANDBOOK of more than 40 pages and conducted a series of teach-ins for ACT UP's general membership. This information was then distilled by the Media Committee for presentation to the press. The FDA action was "sold" in advance to the media almost like a Hollywood movie, with a carefully prepared and presented press kit, hundreds of phone calls to members of the press, and activists' appearances scheduled on television and radio talk shows around the country. When the demonstration took place, the media were not only there to get the story, they knew what that story was, and they reported it with a degree of accuracy and sympathy that is, to say the least, unusual.[16]

While the membership was schooled on this, the national ACT UP chapters were fairly hesitant about the action, believing that a better target would be Congress or the White House. As a concession to these chapters, ACT UP/NY organized a rally outside of the Department of Health and Human Services.[17] It was at this rally, the day before the FDA action, that Vito Russo gave his famous speech, Why We Fight, concluding that “after we kick the shit out of this disease, we're all going to be alive to kick the shit out of this system, so that this never happens again.”[18]

The FDA action was a success, with 1500+ people attending, organized into smaller affinity groups, each urging the FDA to speed up the process of testing new drugs to fight opportunistic infections and AIDS itself. The affinity groups went about this in their own ways, but Vito Russo summed up the goal of the action fairly succinctly: “I would rather take my chances with the side effects of an experimental drug. The side effect of AIDS is death.”[19] The media was largely sympathetic to the action, and ACT UP won support for its cause. In the aftermath of the action, however, there were differing visions for how to move forward, as Gregg Bordowitz recalled:

I felt that it was pretty clear that ACT UP and the AIDS movement was a catalyst for the growing health-care movement at that time. So I was very much interested in that, and that ACT UP could join unions, and the unions could come together. It was this coalition politics idea that sexual politics, and race politics, and feminist politics could come together in such a way with the unions...That increasingly brought me into alienation with the group, because the group was going in another direction. The group did not want to slow down for a long campaign.[20]

While the organization as a whole did not mount a clear campaign toward universal healthcare, by no means was ACT UP singularly focused on access to medication. A common goal cited by members was to get ‘drugs into bodies,’ but as Maxine Wolfe, a veteran ACT UP organizer put it, “it’s not just about drugs into bodies--it’s about the people whose bodies these drugs could eventually get into.”[21] This occurred as the organization’s membership also became more reflective of the trends of the AIDS crisis. Women began joining and forming their own caucuses and committees, as did Chicanos, Black people, Asian immigrants etc. As the organization grew and learned more about AIDS and the AIDS crisis, there was a concerted effort made to spread information as widely as possible, and integrate this education into the cultural particularities of any particular ethnicity or nationality (this largely came through the committees, rather than the general body of the organization).

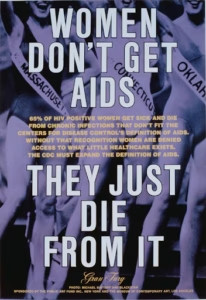

One of ACT UP’s most long term campaigns was their efforts from 1989-1993 to change the definition of AIDS to include women. At the time, women were not included in clinical trials to nearly the degree men were, following a 1977 ruling where the FDA banned most people of “childbearing potential” from clinical studies.[22] As a result, the anti-AIDS drugs that were being tested were not being tested on women. When questioned about this, Fauci gave the women of ACT UP “really thorough arguments explaining why women couldn’t be in clinical trials.”[23] Simultaneously, the opportunistic infections that manifested in women were ignored and not attributed to AIDS, and women with AIDS were unable to receive government benefits that men with AIDS were entitled to. This prompted one of ACT UP’s more memorable slogans: Women don’t get AIDS, They Just Die From It. It also prompted ACT UP to mount a four year campaign to change the CDC definition of AIDS, with Terry McGovern leading a lawsuit against the Social Security Administration for discrimination against women.

By late 1992, it was clear that the CDC was going to change the definition, and a real question arose among the activists: “how many people would lose benefits and how many people would die if they pushed too far?”[24] Initially, the CDC wanted to expand the definition to include bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, and T-cells below 200. Surely, this was a step forward, but it still did not include any opportunistic infections that only women got. ACT UP continued to protest, and by early 1993 the CDC had accepted a new definition that included cervical cancer and endocarditis, but not pelvic inflammatory disease. Despite not winning all of the demands for a new definition, ACT UP succeeded in increasing eligibility for women with AIDS by tens of thousands of people.

The campaign to change the definition was not ACT UP’s only efforts to fight against the oppression of women. The organization also spread its focus toward other issues not directly tied to AIDS, and in some cases formed coalitions with other groups that were ‘united in anger.’ One such action was ACT UP’s most controversial, the Stop the Church action in 1989. This action, done in coalition with Women’s Health Action and Mobilization (WHAM!), protested inside and outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral in NYC, in opposition to Cardinal O’Connor’s homophobic, anti-condom, anti-needle exchange, and anti-abortion teachings. O’Connor had previously been named to Reagan’s AIDS commission and was very vocal about the sinfulness of condoms. He believed that promoting condom use or needle exchange (the reuse of needles was spreading HIV among injection drug users) promoted sin, and thus had to be discouraged. The Stop the Church protest was specifically called in December of 1989 in response to the Vatican’s first conference on AIDS in November of that year. At the conference, O’Connor had declared that “the truth is not in condoms or clean needles. These are lies, lies perpetrated often for political reasons on the part of public officials….the greatest damage done to persons with AIDS is done by the dishonesty of those health care professionals who refuse to confront the moral dimensions of sexual aberrations or drug abuse. Good morality is good medicine.”[25] At the same time, the Senate had voted down the funding of clean needle exchange 99-0.

When Cosmopolitan Magazine ran an article entitled “Reassuring News About AIDS: A Doctor Tells Why You May Not Be At Risk,” which explained, incorrectly, why women were not at risk for AIDS, ACT UP formed its Women’s Caucus and protested the article. They also made a concerted effort to be at the forefront of the science and theories of AIDS, often leading, rather than following, the scientists themselves.[26] For example, ACT UP attended the Fifth International AIDS Conference in Montreal in 1989. They presented thousands of informational booklets to the scientists, detailing how the various bureaucracies actually worked, how studies were actually conducted, and why they felt the need to protest. They placed positive and concrete demands on the scientists and the bureaucracies, which was a clear step in the right direction. But at the same time, the conference showed some of the first signs of a split that was brewing in the organization between those who wanted to ingrain themselves in the government agencies and just get the drugs out as fast as possible (which was surely needed), and those who recognized that AIDS was not just a medical or pharmaceutical problem, but that class, race, gender, and nationality were enormously responsible for how the epidemic manifested itself. The ACT UP members who were interviewed at the Montreal Conference would be the ones to form the Treatment and Data Committee (T+D), which would eventually break off to form the Treatment Action Group, a separate organization.

These members were crucial in planning the action to Storm the NIH, as well. The action itself was heroic. Similar to the FDA action, People With AIDS directly confronted a bureaucracy that had been callously indifferent to their deaths. Chants of “ACT UP! Storm the NIH! This is war! Storm the NIH! ACT UP! Storm the NIH! For the sick! Storm the NIH! For the poor! Storm the NIH!” could be heard at the action.[27] There was a huge diversity of demands made from the crowd, ranging from general calls to ACT UP, to fight back against racism, for injection drug users[28] and people of color to be included in trials, to calls for People With AIDS to be in charge of the bureaucracies and to chart the course of the fight against AIDS. However, the actual demands presented to Anthony Fauci and other bureaucrats, as well as the demands that were won, were not quite the same, as Sarah Schulman makes clear.[29] Future TAG leader Mark Harrington, whose career since 1991 has been as a full-time member of the AIDS industry, said during the action that there was a need “to break down the cult of the expert in society. People with AIDS are the experts on this disease.”[27] Certainly, a fight against cults of expertise and an attempt to broach the gap of the intellectual division of labor must be commended. However, in hindsight, especially with TAG’s invite-only admission policy, it became clear that the goal was not to eliminate the cult of the expert, but simply to transfer the status of expert to the leaders in T+D (later TAG).

This same contradiction between working directly with bureaucracies and being part of a broader fight against all forms of oppression presented itself one month after the NIH action, when the Sixth International AIDS Conference was held in San Francisco (the last time it would be held in the US until the US overturned its laws banning people with AIDS from immigrating). Nearly all AIDS-activist groups nationwide, and even internationally, were boycotting the conference in solidarity with those who could not attend. ACT UPs nationwide were protesting and boycotting, but ACT UP/NY decided to attend on a 170-103 vote. There was an effort to both attend and be in solidarity with those oppressed by the United States’ xenophobic and anti-AIDS immigration policies. When Peter Staley, the poster boy of ACT UP and a future founder of TAG, spoke at the conference, he asked the other ACT UP members in attendance to join him on the stage. As dozens joined him, he said “at this moment, there are others just like us who are trying to get into this conference, but are being barred by the billy clubs of San Francisco police. And there are still others like us who are trying to get through customs at the San Francisco airport, but are being detained instead because they are gay.”[30] He also highlighted where George Bush Sr.’s priorities stood; rather than attending the conference, Bush was at a fundraiser for the arch-bigot Jesse Helms, who had written the immigration bill.

Yet while Staley and other T+D leaders were showing their solidarity with those oppressed by the US state, one of their main goals at the conference was to integrate themselves with state institutions that were dealing with the AIDS Crisis. After the conference, Fauci and NIAID established the Community Constituency Group (CCG) and put anti-AIDS activists on all AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) and Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS (CPCRA) research committees and granted them votes.[31]

As Sarah Schulman explains, as a result of the NIH Action and the Sixth International AIDS Conference, “some people from our community on the T+D side became part of the structure inside the NIH.” These T+D members becoming structurally part of the bureaucratic institutions in charge of the AIDS Crisis was the first clear step toward the leaders of T+D splitting off and forming the Treatment Action Group, or TAG.

TAG and the Days and Years of Desperation 1991-1995

The TAG-split was preceded by infighting among the organization.[32] T+D, the precursor to TAG, had grown to be elitist within ACT UP. Members felt like T+D was growing too cozy with the drug companies that they had been meeting with and had developed their own agenda, separate from the larger body. A motion was proposed for a 6 month moratorium on meetings with drug companies. This sparked outrage, especially when a woman who was not seropositive told T+D members “it’s not like it’s for the rest of your life.” At that point in the crisis, 6 months could very well be the rest of someone’s life.

The divide between seropositive and seronegative members was certainly part of the split, but it was not the crucial component. ACT UP’s origins, as described by many of its members, have been found in the disillusionment that many privileged, middle class, white gays felt when they lost some of their status and felt a much stronger oppression when they got diagnosed with AIDS. This feeling manifested in TAG, a group that was led by Peter Staley (investment banker for J.P. Morgan), Mark Harrington (Harvard graduate), Bob Rafsky (Harvard graduate), Gregg Gonsalves (Tufts graduate, now a professor at Yale).[33] Whereas ACT UP was open to anyone and radically democratic (to a fault), TAG was invite-only.

TAG saw making life-saving medication available as the best way to ‘survive a plague.’ This can be seen by watching TAG’s first press conference. When Mark Harrington was asked why TAG was wearing suits and whether they thought their approach was better than “circling NIH buildings and so forth,” his response was: “I think that we like to keep our options open, but it’s silly to risk arrest and the hassles that are intendant upon it if you can get serious attention and negotiations going with other measures.”[12] To them, if it was available that was enough, because these members were used to having access to whatever was available. Thus working directly with the pharmaceutical companies and government bureaucracies was acceptable because TAG members were used to these institutions being on their side. This ignored the systemic barriers to access that minorities with AIDS faced, and crucially this occurred as AIDS began to infect more minorities.

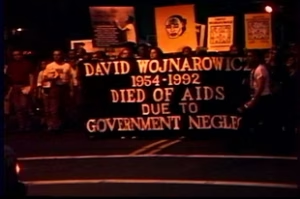

The TAG split left ACT UP in shambles, and the organization never fully recovered. Looking at the actions of the organization, this is clear enough. Whereas before 1991 and the split, the major actions had confronted bureaucracies that were leading to mass deaths of people with AIDS (the NIH, the FDA, Wall Street, Pharmaceutical Companies, the Catholic Church), after the split ACT UP’s actions became much more melancholy and full of mourning. Their 1991 action in protest of the Gulf War was called the Day of Desperation, but this entire period may well be called the years of desperation. There was a turn toward more symbolic actions like the Ashes Action, where relatives and lovers of deceased people with AIDS from across the country met in front of the White House and dumped the ashes and bones of the dead on the White House lawn to bring the death home to President Bush. The rationale for the action, as David Robinson explained in the documentary United in Anger, was to show “the truth--the unvarnished truth--don’t pretty this up in any way. What has come out of this epidemic? It’s ashes, it’s bone chips.”[21] There were more political funerals in the streets as well, and the videos of the funerals show a group that is much closer to despair than anger.

Even actions that previously would have garnered sympathy and increased membership were less effective. When Bob Rafsky interrupted Bill Clinton’s campaign speech to ask what Clinton’s plan was for AIDS, Clinton told Rafsky to calm down. But this did not get ACT UP the same support as it would have if Clinton was a Republican. There was still hope that the Democrats would be better (despite the constant problems ACT UP had in New York and California fighting against the Democratic Party), and people held out hope for political change from the top, rather than keeping up pressure from below.

During the Clinton years, AIDS activism declined tremendously. Documentaries and books on the topic generally gloss over these years until the release of HAART therapy, the ‘solution’ to the crisis. ACT UPs across the country began to dissolve, and those that stayed active were a shell of their former organizations. TAG worked with, rather than against, those in charge of the AIDS crisis. As always, the Democrats co-opted and then crushed a liberation movement.

We can clearly see that the Democrats were no allies or friends of those fighting against AIDS. Just as quickly as they paid lip service to certain reforms that could have helped PWAs (though never even paying lip service to fighting the larger structures or capitalist system that led to the epidemic), they backed away from these promises whenever they were potentially implemented. Yet there should have been another, albeit smaller, potential ally of the PWA movement. One of the most striking things about reading memoirs from PWAs and histories of the crisis is the complete absence of any organized left from the narrative. The closest I have come across is Cleve Jones mentioning that before the AIDS crisis the Socialist Workers Party was active in fighting LGBT discrimination in California. Yet even in Jones’s recollections, the SWP fades from the narrative the second that the AIDS crisis appears on the scene. A look through the archives of some of the major socialist publications at the time is telling. The Spartacus League, notorious as they are, had only mentioned AIDS once in passing before 1984, when they addressed a letter to the editor questioning their lack of coverage of the AIDS crisis in light of their previous attention to homosexual oppression. Their response is striking, and indicative of the insanity of the left at the time:

The delay in our AIDS coverage was due to nothing more remarkable than repeated, frustrating delays in producing the new W&R (nine months between the last two issues), resulting mainly from the demands of our important legal defense campaigns, with the W&R editor being heavily involved in the publicity work around these cases. We invite D.F. Moore to consider in particular our forthright defense ofthe "North American Man/Boy Love Association" against the vengeful and reactionary "age-of-consent" crusade (see "Moral Majority Witchhunt Against Gay Activists-DefendNAMBLA!" WV No. 321, 14 January 1983).[34]

While one of the largest crises of the 20th and 21st Centuries was developing, they did not have the time to jump to cover it because...they had to argue against age of consent laws.[35]

Other publications have not fared much better: Monthly Review did not cover AIDS until the mid-80s, and has not had an article on the crisis in the US since 1989. DSA appears to have ignored it until the 1990s. Labor Militant held a ‘workerist’ attitude to AIDS and the gay liberation struggle generally. Because these issues did not directly relate to the unions or the ‘mass organizations of the working class’, they were not deemed important enough to warrant coverage or consideration-- though, to my knowledge, there was not active homophobia on the part of the organization. The Maoist Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) was fairly emblematic of groups at the time, particularly those that defended, to one degree or another, the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China. The RCP, as stated in their program, viewed homosexuality as:

perpetuated and fostered by the decay of capitalism, especially as it sinks into deeper crisis. This is particularly the case because of the distorted, oppressive man-woman relations capitalism promotes. Once the proletariat is in power, no one will be discriminated against in jobs, housing and the like merely on the basis of being a homosexual. But at the same time education will be conducted throughout society on the ideology behind homosexuality and its material roots in exploiting society, and struggle will be waged to eliminate it and reform homosexuals.[36]

The article that this program is mentioned in acknowledges that the AIDS pandemic was being used to further oppress homosexuals, and goes as far as to say that the RCP should work in united fronts with other revolutionary groups to defend these rights. This is certainly a positive. Yet the underlying premise of any positive position that the group took was that homosexuality was a deformity caused by the decline of capitalism, that one of the end goals of a socialist revolution would be to ‘reform homosexuals’ into heterosexuality. Thus the group did not defend the rights of homosexuals as homosexuals, but defended the rights of, in their view, currently confused and future heterosexuals. The prospect of such a position gaining any traction in the fight against AIDS, especially among those actually affected by AIDS, was slim to none.

Yet not every organization was quite that bad. The Socialist Workers Party paid consistent attention to the issue, though their attitude tended to be “how can this benefit us?”. It does not appear that they actually integrated themselves into the movement, preferring to sell papers from the outside. In effect, even when they did organize around the issue, or speak at anti-AIDS demonstrations, they were not integrated into the PWA community, they did not see the world in the same way that PWAs did. A prime example of this is that in their letters to the editor, they were repeatedly asked to refer to those infected with HIV/AIDS as PWAs, yet they continued to refer to them as AIDS patients or AIDS victims. Workers World Party was the only left-wing group directly involved in organizing the Lesbian and Gay Rights March in 1987, where the AIDS quilt was first unveiled. This leads us to our next question: if some groups did not ignore the issue, and in fact actively participated in the movement, why do they not appear in the histories? Why do the histories of the PWA movement and the general movement against the AIDS crisis simply not include socialist groups? Part of this is due to who writes the history. As AIDS became part of ‘normal’ life, the vision of groups like ACT UP and the movement as a whole was painted as our post-HAART society, where things remain the same but AIDS is not automatically a death sentence any longer. This is certainly part of the story, but by no means is it the whole, or even a large part. The real reason for the absence of socialist groups from the history of the AIDS crisis is that, by and large, these groups made no effort to integrate themselves into the history of the crisis. Walter Lippmann noticed this in 1987, when he was writing about the Lesbian and Gay Rights March: “Finally, a note about the political left. With few exceptions (notably the Workers World Party and Line of March), groups on the political left did not build the march or actively encourage participation by their members. At best, they saw the mobilization as a place to sell their literature. As a result, they stood quite literally on the sidelines.”[37]

Despite the lack of attention that the organized left paid to the gay liberation struggle and the fight against AIDS, there is a real history of Marxists fighting for the democratic rights of LGBT people that needs to be reclaimed. It is important to trace this history, if only to show that there is no inherent antagonism between the left and LGBT liberation. As early as 1897, many members of the German Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), the largest Marxist party in the world, were organized in Die Wissenschaftliche Humanitäre Kommittee (The Scientific Humanitarian Committee), “an organization conceived to combat the anti-homosexual statute (paragraph 175) in the German penal code.”[38] The SHC set out to educate the public on the reality of homosexuality:

Based on proven research and the personal experience of thousands, we are shedding light on the fact that as far as people of the same sex are concerned, so-called homosexuality, it is neither a vice nor a crime, but rather a feeling deeply rooted in the nature of a number of people.[39]

August Bebel, the most prominent worker-leader in the SPD, was an early proponent of the repeal of Paragraph 175, and Magnus Hirschfeld, the leading sexologist and proponent of the normality and democratic rights of LGBT people, was a vocal supporter of the SPD, joining the organization in 1923. Hirschfeld even spoke on November 10,1918, the first day of the German Revolution, before a Soviet of workers and sailors, proclaiming:

the union of all citizens of Germany, mutual care for one another, the evolution of society into one organism, equality for all, everybody for all and all for everybody. And what we want even more: the unity of all nations on earth; we must fight against hatred of other nations, fight against national chauvinism. We want the end of economic and personal barriers between nations, and the right of the people to choose its own government. We want a judiciary of the people, and a World Parliament….Citizens of Germany, let us have confidence in the new revolutionary government. I ask you all to support it, so that the country can live in peace and order. Then we can look forward to leading again, soon, a life of human dignity and pride.[40]

It is significant that the revolutionary government immediately invited Hirschfeld to speak at a public gathering. At the time, Hirschfeld had already published numerous sympathetic books on LGBT issues, including Sappho and Socrates: How Does One Explain the Love of Men and Women to Persons of Their Own Sex?, The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress, and Homosexuality of Men and Women, all intended to educate the public to be more sympathetic and understanding of gay people, and to allow for gay people and lesbians to flourish and be accepted in society. This was not just a matter of Hirschfeld supporting the SPD-- the support ran both ways. This is not to say the party was a utopia for LGBT people. Party papers such as Die Zukunft (The Future) and Vorwärts (Forward) were responsible for ‘outing’ multiple capitalists or government officials. The intention here was two-fold. In part, the papers intended to show the hypocrisy of homosexual oppression. If a capitalist magnate like Alfred Krupp was engaging in homosexual activity, why was this still being punished under the law? This was a positive intention, if flawed in execution, and one that ACT UP and Outweek Magazine frequently engaged in and argued over. However, the SPD papers also intended to expose the “bourgeois vice”[41] of the capitalist class and government. The intention here was to attempt to show that capitalism itself led to the ‘degeneracy’ that they were exposing. In this sense, we can see the SPD tradition of outing as both a precursor to ACT UP and to the RCP position on AIDS (for the democratic rights of gay people while attributing their homosexuality to capitalist decay). It is significant that in the 80 years since the SPD did its outing, the organized left had regressed on the question, while holding onto the worse of the two intentions behind the outing.

The reason for this must be analyzed. While the SPD failed and refused to take power in the German Revolution and was eventually decimated by the Nazi seizure of power, the Bolsheviks did take power, and by the 1980s the Bolshevik impact on the organized left was much greater than the SPD. After the Bolshevik revolution, the Tsarist penal code was abolished and rewritten. The ban on homosexuality was not written back into the Soviet laws; homosexuality was decriminalized. As Fred Weston makes clear in his introduction to Dr. Grigory Batkis’ The Sexual Revolution in Russia,

‘acts of homosexuality…and any other forms of sexual pleasure’ had the same legal status as heterosexual relations, adding that, ‘All forms of intercourse are treated as a personal matter.’ The state intervened only if violence, abuse and coercion were involved. This was an extremely advanced outlook on same-sex love and remained the case until the Stalinist political counter-revolution reversed everything back to the old Tsarist measures of repression.[42]

Batkis explicitly contrasted this with Bourgeois Europe, stating “Whilst European legislation defines all this as a breach of public morality, Soviet legislation makes no difference between homosexuality and so-called ‘natural’ intercourse.”[12] Clearly, there was a basic respect of the rights and humanity of homosexuals brought on by the revolution.

This did not last. There is not room in this piece to discuss in detail the reasons behind the rightward turn on social questions under Stalin. Suffice it to say that homosexuality was recriminalized in 1933, with a penalty of years of hard labor. This went hand in hand with the banning of abortion, and a return to a more patriarchal and pro-natalist view of the family. With the lack of democracy in the Communist International, this view on the gay question was transmitted to the national communist parties throughout the world. To be gay was antithetical to being a communist.

In the United States, this led to a disastrous situation where Harry Hay, a leading member of the CPUSA, was expelled from the party in 1951 after coming out of the closet. In the period of McCarthyism, he was considered a security risk;[43] additionally, the party did not allow homosexual members.[44] Hay had secretly founded the Mattachine Society, the first openly gay organization in the United States, in 1950. Thus from the start, the fight for gay rights in the United States was structurally divorced from Marxism. Though the Stalinist turn to social conservatism lay at the root of this divorce, it would be a mistake to claim that only Stalinists (or Marxist-Leninists depending on terminology used) were responsible. The entirety of the communist movement--Marxist, Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyist, Maoist etc--at various points, and to various degrees, either ignored the gay liberation struggle or viewed homosexuality as a symptom of capitalist decay. Even today, we see many groups with anti-trans positions, and some of the more dogmatic sects believe that homosexuality must be bourgeois decadence because the glorious comrade Stalin said so, or because the CCP has an anti-LGBT line.

This is all to say that proclaiming oneself to be a Marxist does not automatically lead to being, in the words of Lenin, a “Tribune of the People.” Conscious effort must be made to link the revolutionary struggle of the working class to the liberatory struggle of each and every oppressed segment of capitalist society. As Engels wrote in the 1888 English Preface to the Communist Manifesto, the working class “cannot attain its emancipation from the sway of the exploiting and ruling class — the bourgeoisie — without, at the same time, and once and for all, emancipating society at large from all exploitation, oppression, class distinction, and class struggles.” The linking of the struggles of the oppressed to the class struggle is a necessity because the proletariat is a vast, expansive class. What links the class together is its dependence on the wage fund for its own reproduction--not any part of its identity. Thus to deem certain identities as less working class, or even outright bourgeois, is to weaken the unity of the class. Further, to view these sites of struggle against oppression as solely a place to recruit, rather than part of the broader struggle against class society, is to weaken the ties between the struggle for the emancipation of the working class and the emancipation of the vast majority of society.

While this inattention to the AIDS crisis and the gay liberation struggle was the reality of the left, it did not have to be. We have seen the history of the early Marxist movement and its stances on what was, at the time, deemed “the so-called homosexual question.” We should reclaim this history, and make every effort for the future to see a Marxist movement that takes care to integrate itself into and lead struggles against all forms of oppression. However, the struggle against AIDS did not go that route. As it happened, ACT UP and the struggle of PWAs did not have a true ally in the organized left, and the election of Clinton, combined with the failure to find a cure and the continuous death of leadership, led to the effective collapse of ACT UP as an organization in the early-mid 1990s.

ACT UP survivors have reflected on the collapse of the organization, and the general consensus is some combination of false hope in the Democratic Party, the death of the activists themselves (as well as the general despair of watching friends and activists in the struggle die), the TAG split, and the lack of media attention and sympathy that actions received once the Democrats took power.[45] By 1995, HAART came out, and the story of the crisis generally ends there.

The Crisis After the Crisis

HAART stands for Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. This is a therapy whereby people with AIDS are given a combination of antiretroviral drugs at the same time to suppress their HIV/AIDS and stop its further progression. When HAART first came out, there was widespread disbelief. Any number of drugs and holistic remedies had been claimed as the ‘cure’ for AIDS, and by 1995 people with AIDS were extremely skeptical whenever a new ‘cure’ was released, especially after the study that showed that AZT, the first anti-AIDS drug, was essentially ineffective after a few weeks. But HAART proved to be the real deal. Doctors and people with AIDS describe the Lazarus effect that the combination therapy had on the afflicted. People on their deathbeds regained life and energy; anecdotes of people with AIDS making their same rounds but without the use of a cane or wheelchair were not uncommon. A real solution seemed to be at hand.

Without question, HAART is an incredible innovation of modern medicine, and it has prolonged and improved the lives of a truly countless number of people with AIDS. While there were initial problems with the therapy (some had to take up to 24 large pills daily, at specified and regimented times), modern HAART therapy requires only a few pills daily. Initially, some people with AIDS quit HAART because of the side effects, but today these are far less severe. The problem lies less with HAART than the context in which it has been introduced.

HAART remains prohibitively expensive. As of 2018, even with some generics, the annual cost was around $36,000 per year, with annual increases in price larger than the cost of inflation. In the global south, countries have attempted to create or import generic HAART medications, only to face lawsuits from American pharmaceutical corporations. This same imperialist posturing has been responsible for the embargo on Cuba, which, through an ironic accident of history, has prevented Americans from having access to Cuba’s revolutionary elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission.

The introduction of HAART also left people with AIDS to rebuild their lives.The future did not exist for them, and suddenly, overnight, it was back. Many people with AIDS were unable to adjust to this new reality. Many had been unable to work for years, expecting to die any day. The gay community after HAART faced a crystal meth crisis, as many sought solace in drugs. The gay community in general, and people with AIDS in particular, had not really processed their grief and trauma during the AIDS crisis. HAART forced the burden of this trauma on people overnight. In a society that ignores mental health, and hides mental healthcare behind cost-prohibitive barriers, this is a recipe for disaster.

HAART has not eliminated AIDS. Instead, it has pushed it out of the public eye, onto the most oppressed layers of society. To quote AIDS historian Sarah Schulman

However, while activists were able, in a sense, to beat HIV, they could not beat capitalism. And so, today, because of the greed of international pharmaceutical companies and various health industries, large numbers of people with HIV in the United States and around the world cannot receive medications that already exist. For this reason, around three-quarters of a million people throughout the world still die every year of a disease that is entirely manageable.[46]

Black Americans are only 13% of the US population, but nearly half of new HIV/AIDS cases; it is expected that half of gay black men will contract HIV at some point in their life. AIDS is by no means gone from society, but it is out of the spotlight. The tens of thousands of yearly deaths from AIDS domestically, and the hundreds of thousands to millions of deaths worldwide, are ignored. The mainstream press does not report on deaths from AIDS, except to occasionally mention the plight of the ex-colonial countries, neglecting to give even a hint of an analysis as to why AIDS continues to plague those countries so much more than imperialist countries. AIDS in the imperialist countries is almost entirely out of sight, out of mind, despite tens of thousands of yearly deaths in the United States, disproportionately amongst the oppressed and internal colonies of the US. This makes clear the need for an independent press that is not beholden to the capitalist class and its pharmaceutical and insurance corporations. The problem has not gone away, and will never go away so long as capitalism continues to exist. But this point will never be made or put front and center in any press dependent on and beholden to the capitalist system. Even in ACT UP, there was a correlation between the slow decline of the organization from 1991-1996, and the collapse of Outweek Magazine in 1991.

Many still die from AIDS every year-- and these deaths are preventable; HAART can sustain the lives of people with AIDS, and more recent innovations like PrEP can reduce the viral load (the amount of HIV present in the bloodstream) to the point of appearing uninfected, drastically reducing (some have argued that it even eliminates) the possibility of transmission. The only thing stopping this from becoming a reality is the monopoly that the pharmaceutical companies have over the production of anti-AIDS drugs, and the profit motive that requires a continued supply of people with AIDS to be forced to buy those drugs.

This is a trend that we have seen repeated during the Coronavirus pandemic. We can look at the difference between wage workers dying, losing their jobs, or working in masks in production or the service industry, and compare that experience to white collar and middle class workers taking vacations while working and working from the pool. For one group, the pandemic has been an earth-shattering experience that has fundamentally shaped people’s perceptions of the world; for the other, it has been at most a minor inconvenience, and in many cases an actual benefit, as the realities of working from home allow for much greater choice in how these workers allocate their time. On a more global scale, we can see the same pandemic imperialism at play. Millions and millions of vaccines are hoarded in the US, even if, like the AstraZeneca vaccine, it has not yet been approved for use in the US. For the ex-colonial countries, vaccines are largely unavailable, and workers and peasants have a much harder time taking the necessary precautions to try to minimize the risk of infection.

At the same time, we have seen a complete inability from the organized left to respond to the pandemic. Repeated articles and speeches about the inhumanity of the response to Covid have been made, but there has been no large, sustained campaign to nationalize or socialize the pharmaceutical industry, no larger push for universal healthcare, no organized education about Covid, the vaccines, or immunology. The capitalist class and its state has been trusted with all of this. As we have seen, they have failed. This can be clearly contrasted with ACT UP’s efforts to democratize knowledge and to educate as many PWAs and people at risk of becoming infected with AIDS, as well as the broader public, about the realities of the virus. This was not easy work. It took conscious effort. Eventually, however, members realized that it was possible to understand AIDS and to educate others about the pandemic. As Dudley Saunders recalls:

I remember trying to fight, saying, no, no, let’s really listen, let’s really all understand this. It’s not brain surgery. This stuff really can be understood – or, maybe brain surgery can be understood, that’s the point.[47]

This is a very different attitude to science in a pandemic than we have seen during Covid. ACT UP did not make the opportunist decision to leave science to the capitalist state, nor did they make the ultra-left mistake of ignoring science simply because it was produced under a capitalist state. They analyzed the science that was produced, made every effort to influence what was studied further, and continued to agitate against the very institutions that they recognized were needed for their own survival. When ACT UP dropped its oppositional stance and held out faith in Clinton, the organization effectively collapsed at the national level.

The need for education and an effective press are not the only structural lessons that can be learned from AIDS. In its heyday, ACT UP’s oppositional stance to both capitalist parties is something all socialist organizations must take heed of. During Covid, there has been a disturbing amount of trust placed in the intentions of the federal government with the calls for more and more lockdowns. In most cases, these calls are being made without an additional call for non-essential workers to be paid adequately to stay home, with the necessities of life provided. Without this additional demand, which must be made inseparable from any calls for a lockdown, the left is merely calling for a larger repressive apparatus that will inevitably be used against it. We have already seen this happen in Chile, where bogus concern for social distancing was used to try to break up the general strike. The same process has occurred throughout the US, with curfews being implemented ostensibly to help curb the spread of Covid, but in practice being used to illegalize protest. During the AIDS crisis, this happened too, with calls to close the bathhouses. Importantly, anti-AIDS activists recognized these calls for what they were: an excuse for repression of the gay community. They called for gay men to make the choice to not go to the bathhouses, or to use protection and safe sex methods if they chose to, but many resisted any government mandate for the closure. Instead, the focus was on the need for state support to help fight the pandemic. There was no shaming people for pushing back against further state encroachment in their lives, or even for openly making the wrong choice. Bob Rafsky , the ACT UP militant who Bill Clinton told to “calm down” when Rafsky questioned Clinton’s commitment to AIDS, summed this up best:

The question is what does a decent society do with people who hurt themselves because they’re human, who smoke too much, who eat too much, who drive carelessly, who don’t have safe sex? I think the answer is that a decent society does not put people out to pasture and let them die because they’ve done a human thing.[30]

We are facing a new pandemic, one that the capitalist class would once again rather ignore than handle, one that disproportionately affects the most vulnerable and oppressed layers of society, one that is structurally propelled forward by the capitalist drive toward accumulation and profit. We must learn from previous pandemics and those that tried to solve them. We can revisit Sarah Schulman’s idea of a ‘gentrification of the mind’ that has happened since HAART. The fight against the AIDS crisis; the sense of community forged in struggle; the mutual AID groups that preceded the coordinated resistance to the pace and methods that the capitalist state used to ‘combat’ the crisis--all of this has been forgotten.

Instead, we have seen the same patterns reemerge: denial, then tacit if unsatisfied acceptance of the state response, a culture war over how the state should respond that is not waged on class lines, cooptation by the Democrats without any real change, mutual aid without organization and without political struggle for concrete gains to be won. These same patterns emerged in the AIDS crisis. Covid does not appear to be going anywhere, certainly not as long as capitalism remains the global socioeconomic system. It is paramount that the organized left studies the past with a critical lens, and applies the lessons of the past to our current organizing.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Monte Morin, “HIV's Spread Traced Back to 1920s Kinshasa,” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles Times, October 10, 2014), https://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-hiv-kinshasa-20141009-story.html. ↩

- This occurred when industry leaders began to mix all of their blood and plasma together to cut down on costs, arguing that this was actually safer to do because it would dilute the amount of contaminated blood. ↩

- Gerald Posner, Pharma: Greed, Lies, and the Poisoning of America (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2020), 315. ↩

- Fundamentally this is an expression of capitalism’s tendency toward overproduction ↩

- This is not to say that a cure for AIDS or any sort of drug cocktail that exists now could have been definitely been found in time, but Congolese citizens had reported a disease for years that did not receive any research or attention from Western imperialist powers; see https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2000/10/the-hunt-for-the-origin-of-aids/306490/ ↩

- https://longform.org/posts/1-112-and-counting ↩

- Quoted in Reactionaries Fan Homophobic Hysteria: The Politics of AIDS [Abstract]. (1986). 1917: Journal of the Bolshevik Tendency, (2), 1-24, 9. https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/1917/1917-2-Summer-1986.pdf ↩

- Quoted in France, How to Survive a Plague, 250. ↩

- ACT UP/NY still exists today but does not have the social power, numbers, or national presence that it used to. ↩

- France, How to Survive a Plague, 264. ↩

- France, 302. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid, ↩

- ACT UP Oral History Project, ACT UP Oral History Project, December 17, 2002, http://www.actuporalhistory.org/interviews/images/bordowitz.pdf. ↩

- Quoted in Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UPNY. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2021, 112. ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988,” The Atlantic (Atlantic Media Company, December 10, 2011), https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/12/before-occupy-how-aids-activists-seized-control-of-the-fda-in-1988/249302/ ↩

- Schulman, Let the Record Show, 113. ↩

- https://actupny.org/documents/whfight.html ↩

- Jerry Estill, “AIDS Victims Desperate, Want FDA Help,” Ottawa Herald, October 12, 1988, p. 6. ↩

- Quoted in Schulman, Let the Record Show, 132. ↩

- United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, 2012. ↩

- “Policy of Inclusion of Women in Clinical Trials,” womenshealth.gov, accessed October 1, 2021, https://www.womenshealth.gov/30-achievements/04. ↩

- Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UPNY. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2021, 231. ↩

- Ibid, 262. ↩

- AP, “Vatican AIDS Meeting Hears O'Connor Assail Condom Use,” New York Times, November 14, 19891, sec. A, p. 10. ↩

- Old issues of Outweek, particularly those containing articles from Mark Harrington, show ACT UP members calling for exactly the treatments that would eventually become HAART (the AIDS drug cocktail that ‘ended’ the crisis), followed by frustrated explanation of the various bureaucratic bottlenecks preventing these treatments from being studied. ↩

- United in Anger, 2012. ↩

- Fauci had deemed this group a ‘noncompliant population’ and not allowed them into trials, even though symptoms of HIV/AIDS manifested differently in injection drug users compared to people who contracted HIV/AIDS from sex; Schulman, Let the Record Show, 283. ↩

- Ibid, 535-543. ↩

- France, David. 2012. How to Survive a Plague. United States: GathrFilms. ↩

- Schulman, Let the Record Show, 540. ↩

- Ibid, 541. ↩

- Ironically, Spencer Cox, the only leading member without elite qualifications, was the most influential and the most successful in terms of fighting AIDS, helping get protease inhibitors, including ritonavir, released. ↩

- “On the AIDS Witchhunt,” Workers Vanguard, January 20, 1984, 346 edition, pp. 1-16, 2. ↩

- It deserves to be noted that Sarah Schulman does explicitly mention the Spartacists as one of the only revolutionary left groups to be accepting of homosexuality and fight actively for equal rights. The intention here is not to pretend that they were homophobes or did not care about the AIDS crisis, but to show that their priorities were radically out of line. ↩

- Quoted in “On the Question of Homosexuality and the Emancipation of Women,” Revolution, 1988, pp. 40-55, 41. ↩

- Walter Lippmann, “Lesbian and Gay Rights: Over Half a Million March on Washington,” Bulletin in Defense of Marxism, December 1987, 47 edition, pp. 1-36, 14. ↩

- Elena Mancini, Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom, 1st ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 91. Parentheses my own. ↩

- Quoted, Ibid. ↩

- Quoted, Ibid 115. ↩

- Quoted, Ibid 95. ↩

- Dr Grigory Batkis, “The Sexual Revolution in Russia,” ed. Fred Weston, In Defence of Marxism (In Defence of Marxism, May 2, 2018), https://www.marxist.com/the-sexual-revolution-in-russia.htm. ↩

- A regular tactic of McCarthyism was to threaten to out gay men that were in the closet if they did not snitch on their comrades. ↩

- Leslie Feinberg, “Harry Hay: Painful Partings,” Harry HAY: Painful partings, June 28, 2005, https://www.workers.org/2005/us/lavender-red-40/. ↩

- A good resource is the ACT UP Oral History Project, with interviews with nearly 200 former ACT UP members. Sarah Schulman’s recent history of ACT UP New York, “Let The Record Show,” is based on these interviews, as well as Schulman’s own time in ACT UP. ↩

- Schulman, Let the Record Show, 10. ↩

- ACT UP Oral History Project, ACT UP Oral History Project, 2003, http://www.actuporalhistory.org/interviews/images/saunders.pdf. ↩