Joseph Robinette Biden’s first year as president is only a few months from coming to a close. So far, his policies have been perplexing. The man who was attacked on the campaign trail for just being more of the same, a disaffected racist old man representing the worst of Washington’s inertia-ridden gerontocracy, has somehow become an object of critical support or (even worse) outright praise from some on the Left. He hasn’t changed much; he is still a disaffected racist old man after all. What has changed, however, are his political program and rhetoric. It turns out you can teach an old dog new tricks… but after everything, they are little more than that. In the face of mounting crises, the new administration and the big capitalists behind it have developed a new political strategy to prop up Biden’s hegemony. The Left has to respond to this with our own counter-hegemony; we cannot simply fall into the same complacent strategies that have defined our organizations for generations. In order to at least achieve an understanding of the issue, it is important to both examine Biden’s reforms for what they truly are and place them in a historical context.

The New Keynesianism?

With unprecedented crises presenting themselves to the U.S. establishment, encapsulated in the worldwide pandemic that has killed millions and slowed down the functioning of not just U.S. capitalism but the entire global market, the ruling class is in need of a new strategy. The neoliberal system has struggled to contend with the pandemic; despite how it may seem from the disaffected and distant appearance that mainstream politicians and capitalists put on, they’re not ignorant. The pandemic has seriously challenged the state of affairs that they had grown so used to. And so, despite all of the assurances that “nothing would fundamentally change” under his presidency and that “no one’s standard of living will change,”[1] Biden has become the figurehead of an attempt at a strategic reorientation of U.S. capitalism and imperialism.

Biden’s economic plan is encapsulated in four new programs: the American Rescue Plan, American Jobs Plan, American Families Plan, and the Made in America Tax Plan. Only one of these, the American Rescue Plan (ARP), has actually been put into effect and it has been the target of some scorn in the Left-wing commentary sphere for having less stimulus money than was promised for the working-class. Since its passage in March, the ARP has been the fixation of a debate over infrastructure spending that is still ongoing. Biden has put forward plans to put money (albeit meager amounts) into the hands of U.S. citizens, funnel cash into infrastructure projects, and provide financial support for childcare and higher education, all built on the foundation of a tax plan that claims to push for higher taxes on the very rich. On the face of it, this is just what much of the Left wanted: a state willing to tax the rich to fund social programs. The government is finally “doing stuff”, as the meme of professor Richard Wolff parodying superficial reformism goes. So, is this socialism?

Of course not! But one could be forgiven for thinking that these plans and programs go much further than they really do. The token Leftists in Congress seem all too ready to laud every praise possible on them. The left flank of the Democratic Party, Bernie and all, praised Biden’s administration as “the most progressive since FDR.”[2] Even outside of Congress, Faiz Shakir, campaign manager for the Bernie 2020 campaign, piled the praise on thick:

“I think Biden understands that there is a real opportunity here to deliver lasting, legacy-defining improvements to America that otherwise would never get done. He wanted an FDR-modeled presidency and this would be a huge, huge investment in working people on a scale that we have not seen since FDR.”[3]

The comparisons to Franklin Delano Roosevelt keep on coming! It seems that the forces of liberalism and social democracy, whether in the halls of power or in the press, have been taken by the allure of Biden’s spending proposals. It would seem that John Maynard Keynes has been reborn, and generations of neoliberal orthodoxy done away with! Nothing could be further from the truth; Joe Biden is not an FDR for the 21st century, and socialists should not be wasting their time offering any amount of support to him or his programs.

The New Deal, while undeniably important to U.S. history and economic recovery, was not the kind of radical investment in working people that it is often made out to be. Rhetorically, FDR did lean into a somewhat radical posture, one that even got the support of the Communist Party, labor unions, and other progressive elements. Economically, however, his reforms were a new form of bourgeois domination. At the very least this is something held in common between FDR’s reforms and Biden’s. The earliest parts of FDR’s reforms used state spending and public employment to bolster big business, not to bring in labor into any sort of direct relation with economic power. It was only during the conditions of wartime that organized labor acquired any sort of prominence in a compromise borne out of the constant pressure put on the state, the ultimate impetus for the more progressive parts of FDR’s agenda.[4]

In a recent article for Tempest magazine,[5] Ashley Smith terms Biden’s ambitious program as “Imperialist Keynesianism,”[6] a Keynesian break with neoliberalism brought about not by pressure from the working-class but by the continuing crises of U.S. capitalist imperialism, namely the increasing unprofitability of U.S. businesses. He also describes how this crisis of declining profitability has been made sharper by the rise of Chinese capital on the world stage, with China as the only country whose GDP grew in 2020[7] and ever higher numbers of Chinese companies intervening in critical industries. Smith argues that Biden’s four-part plan, and his Keynesian turn more generally, reflects the need of the U.S. bourgeoisie to respond to the issue of increasing unprofitability and to out-compete China. While Smith’s article is an invaluable appraisal that provides much needed context and information regarding Biden’s plans, in truth Biden does not represent a return to Keynesianism.

It is undeniable that there are Keynesian elements in Biden’s plans; the idea of an economic revival using high spending is typically Keynesian, after all. However, Biden’s break with neoliberal orthodoxy is only partial. It would be impossible for it to not be; the material conditions of the present are significantly different from the Keynesian world order of the mid-20th century. Additionally, it is not outside of the realm of neoliberalism to intervene in the economy in order to maintain competitiveness. It was the German ordoliberals, growing out of the same intellectual environment as neoliberalism, who built the so-called “social market economy” in post-WWII West Germany. They were not enthusiastic supporters of social welfare programs, but built on longstanding German social security systems to develop a free market economy with some support for lower class Germans in an effort toward a kind of ideal competitiveness.[8] The neoliberal argument for state welfare programs was formulated by German ordoliberal theorist Wilhelm Ropke, who described their “social market” as a system that “had the task of guaranteeing individuals a stable, secure framework of existence.”[6] In the words of Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, in their work on neoliberal society, “Social progress took the form of the constitution of a ‘popular capitalism’ based on encouraging individual responsibility through the constitution of ‘reserves’ and the creation of a personal estate obtained through work.”[6]

This neoliberal view of social welfare is often reflected in how Biden presents his programs. He repeatedly describes how his plans will rebuild and revitalize an ever-suffering U.S. middle-class. Although this is little more than posturing, it is important to recognize that in many ways the image of the “American middle class” is very much like the ordoliberal vision of the creation of a personal estate through work. Additionally, Biden’s programs are explicitly designed to make U.S. corporations more competitive on the international stage with China. Smith mentions this in his appraisal of Biden’s economic plan, and she is very right to do so. Biden’s economic program is a nationalist attempt to make the U.S. middle-class competitive at home and U.S. corporations competitive abroad. It is a very different vision from FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights, with its declarations of essential needs that must be met and the humanistic ideology underlying it, even as FDR’s actual economics were more focused on the big bourgeoisie.

Joe Biden’s program is not a full return to Keynesianism. It is a synthesizing of Keynesian strategies into a neoliberal framework. He is using state spending to improve the health and competitiveness of the U.S. bourgeoisie and labor aristocracy, with an understanding that the ultimate goal of this is not to make the system work for everyone, but rather to defeat Chinese competition and resolve the U.S.’ own internal contradictions. Smith is right that Biden’s policies are, in a sense, of a new type distinct from old Keynesianism, even if the identification of this turn as “Imperialist Keynesianism” is rather confusing since the Keynesian economic systems of old were themselves imperialist. That said, it is incorrect to see this as a full break from neoliberalism. It is a synthesis.

Although not a full break from the preexisting economic order in the U.S., Biden’s pseudo-Keynesian neoliberalism still requires a shift in rhetoric and ideology. Biden, like any other political leader building a new political project, requires hegemony. For Biden, the overwhelming majority of the process of constructing hegemony has already been done for him: the liberal media apparatus, the deeply ingrained two-party system, the legitimacy of having won the election, and the powerful idea of bourgeois “common sense” all combine to form its basis. But increasingly, these hegemonic institutions and understandings are undermined and challenged. There are many millions of Americans who do not trust media narratives nor believe that Biden won the election. This is not to say that those people have the most accurate perspective, but rather to point out that in many ways the traditional hegemony of the neoliberal age in the U.S. is in decline, along with the country's place in the world generally. Biden’s administration requires a new hegemony.

Enter the ideology of “national unity.” Beginning with his inauguration, Biden has been justifying his administration’s actions with reference to this guiding principle. Only two weeks after the events of January 6th, Biden declared that his administration’s central goal would be to develop this unity, although he refrained from clearly defining its content. He stated “To overcome these challenges [referring to economic, racial, and pandemic issues], to restore the soul and secure the future of America, requires so much more than words. It requires the most elusive of all things in a democracy - unity.”[9] This isn’t merely a statement of preference, this is a hegemonic justification.

While the commentators may compare him to FDR, Biden seems to see himself as an Abraham Lincoln in a sea of disunity. Whether a genuine belief or not, Biden has entered the presidency in the midst of the liberal conversation on “polarization” and “division”; on top of this, he implicitly compares himself to Lincoln in his inaugural address: “In another January… in 1863 Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. When he put pen to paper the President said ‘if my name ever goes down in history, it’ll be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.’”[10] Biden is no Lincoln though; if anything, he’s more like a Copperhead,[11] the Democrats who wanted a peaceful resolution with the seceded states. Knowing that the ostensible left-wing flank of his party won’t do much to challenge him, he capitulates to the right-wing of the Democrats and the reprehensible Republicans in order to get his meager reforms at the very least on the floor. This is the arena of his national unity; not the kind of unity seen in Lincoln’s National Union Party, but reconciliation with some of the worst of the worst in our heinous government in order to get token reforms passed. The rhetoric and ideology is only the justification.

The great theorist of hegemony, Italian Communist Party cofounder Antonio Gramsci, also wrote of the need for the socialist movement to have a counter-hegemony of its own, an ideological and political infrastructure to build working-class consciousness and solidarity, and to challenge bourgeois hegemony. The U.S. Left has never had this kind of counter-hegemony, and the few times it has grasped the beginnings of such a project, it has abandoned that path for capitulation and tailism. With an understanding of Biden’s economic program and hegemonic process in mind, we can look to the experiences of the revolutionaries of the past to see what worked and what didn’t in building socialist counter-hegemony.

From Bismarck to Biden

Biden’s four part economic plan and his hegemonic ideology of national unity are far from novel. The favorite of every conservative and “apolitical” enthusiast of European history, German Imperial statesman Otto von Bismarck, attempted a similar strategy to undermine and subsume the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and its supporters during the late 19th century. Attacking and undermining the Social Democrats was a major priority of Bismarck not only for the sake of anti-socialism, but also because, just like Biden, he was building a new hegemony: that of the German Empire. However, unlike Biden, this was a hegemony in its infancy, the beginning of empire; Biden is at the tail end of empire and having to build new political projects in desperate attempts to revitalize the institutions he presides over. In attacking the Left to build this hegemony, Bismarck’s approach was two-pronged: a program of social welfare and nationalizations bemoaned as “State Socialism” by his laissez-faire liberal opponents on the one hand, and the dreadful and repressive Anti-Socialist Laws on the other.[12] And yet, in spite of this attack from two sides, the SPD continued to grow and the German Empire that Bismarck invested so much into establishing would collapse to a working-class revolt, albeit one put down, ironically enough, by the Social Democrats themselves. What can be learned from this trying experience of the German Left?

“State Socialism” was not a singular law or program; rather, it was a lengthy process of legislation that began in the 1880s and continued, in one form or another, even after Bismarck’s dismissal from the position of chancellor in 1890. It should not be presumed that Bismarck’s program of “State Socialism” was aimed solely at undermining the support bases of the Social Democrats; rather, just like Biden’s four part plan, they had a primary economic purpose unique to the conditions and needs of the German bourgeoisie and state. Even before the beginning of what is most commonly termed “State Socialism,” Bismarck was engaging in economic policy that would make Biden blush. I sincerely doubt that there is anyone in the Biden cabinet who wants to fully nationalize our rail system. Bismarckian nationalizations were not single mindedly aimed at the Social Democrats; they also helped the German Empire to build up its own economic institutions and infrastructure. Biden’s spending schemes similarly are focused on building up U.S. capital.

Beyond simple nationalizations, “State Socialism” proper began with some of the first modern social welfare programs in Europe. Bismarck’s system of social welfare, beginning with the Health Insurance Bill of 1883 and culminating with the Old Age and Disability Insurance Bill of 1889, was the ultimate root of the ordoliberal social market scheme discussed earlier.[13] These were not high minded plans to bring economic justice or empower the poor; Bismarck was not some kind man of charity, nor was he some sort of proto-Keynesian ahead of his time. The health insurance scheme passed in 1883 was not a modern wide-reaching nationalized medical system; rather, it was a localized plan where funds were divided unevenly between employers and workers, with fixed prices for certain medical services.[14] And yet it was far more ambitious than Biden’s feeble attempts to shore up the fractious neoliberal Obamacare in lieu of real nationalized healthcare or the ever popular Medicare for All.

The following year, Bismarck’s coalition passed a bill to provide insurance to workers, more specifically victims of workplace accidents. Even more so than the Health Insurance Bill of 1883, the Accident Insurance Bill of 1884 was nearly entirely predicated on trying to put a wedge between workers and the Social Democrats, the idea being that if the imperial government provided for workers in their time of need, they wouldn’t go to the Left for that support. Five years later, in 1889, the Bismarckian coalition passed a pension law for workers above 70. However the program was financed by a tax on the working-class![15] Even when trying to use imperial state power to appeal to workers, Bismarck couldn’t help but push them down for the state’s gain.

Despite their shortcomings and their other focuses, these programs were unified around one major goal: breaking apart the social base of the Social Democrats. This was not simply a pipe dream coming down from on high; Bismarck was not the only man in Germany who wanted to use social welfare for his own gain. During the 1870s, a Christian welfare movement emerged in Germany, one that actually became an issue which some Social Democrats responded to.[16] Bismarck was not an idealist partisan of this movement for social Christianity; he was simply using them to his advantage. By implementing social welfare legislation, Bismarck and his coalition were able to placate and offer support to the movement for social Christianity, while denying the Social Democrats the opportunity to rally their base around the demands for these reforms. This leaning toward the Christian social movement was evident when, toward the end of his tenure, Bismarck broke with his traditional political alliances to form a coalition with the staunchly Catholic Center Party; he was willing to go against his longstanding campaign to assert Protestantism on the German Empire in order to keep out the Social Democrats. The Social Democrats did not stand by and feebly criticize Bismarck either. Many of them recognized that the nationalizations, the welfare, and the insurance programs were actually going to benefit people.[17] Yet, they had the organization and the willpower to push back and present a more radical alternative.[18]

Simultaneous with this legislative strategy for undermining popular support for socialism, there existed the more obvious hammer of the German state as a repressive apparatus, embodied in the 1878 Anti-Socialist Laws. Despite the plural name, this was one act, which was extended four subsequent times after its first passage; it would ultimately cover the entirety of Bismarck’s chancellorship. This law banned any group or individual conference with the aim of establishing socialism or spreading socialist ideology from meeting. Not only that, it also outlawed several trade unions associated with Social Democracy, enforced the closure of dozens of socialist newspapers, and banned the displaying of any symbols associated with socialist groups. This was the second and more open prong of the Bismarckian reaction.

And yet, in the face of “State Socialist” attempts to undermine their base of support and direct state repression, the socialist movement grew! Once the Anti-Socialist laws were repealed in 1890, the Social Democrats received 20% of the vote in the Reichstag, and by the early 20th century they had over a million members. German socialists were not simply content to sit by and wait for the Anti-Socialist Laws to be pulled back; no, they actively pushed up against them, organized against them, and organized politically in ways that wormed around them! Social Democrats were elected to the Reichstag as independents and, once they had the parliamentary immunity afforded all members of the Reichstag, used it to propagate socialist ideas they would have otherwise been arrested for. When the displaying of socialist symbols was banned, they began wearing strips of red ribbon, or displaying red rosebuds on their lapels, while women comrades would flash red petticoats from beneath their outer skirts to show that they were Social Democrats. They resisted the repression and won out in the end.

Today, Biden has his own petty imitation of Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist Laws, albeit in a much less openly repressive form. In the wake of January 6th and buoyed by the rhetoric of national unity, the FBI, courts, and liberal-leaning social media companies came together in support for a war on “extremism.” On the face of it, this is a liberal response to open conspiracy theorizing on the part of the QAnon movement and other segments of the far Right; in effect, however, this has been used as a bludgeon against the Left as well. This process began under Trump; the federal task force on violent extremism initiated by Bill Barr identified “neo-nazis, socialists, and anarchists,” while Biden’s statement identifies white supremacists and anarchists as simultaneous targets. None of this is as openly repressive as the Anti-Socialist Laws of old; the socialists taken to court are not given nearly as much attention as the German Social Democrats, and often the force of the U.S. state is decentralized into local police forces and social media companies. Left-wing meme groups being banned on Facebook isn’t comparable to Social Democratic newspapers being banned; but the many activists arrested and taken to court in the aftermath of last year’s George Floyd uprising can be seen very much as the 21st century U.S. form of the martyrs of the Anti-Socialist Laws.

The U.S. Left has never been as strong as the historical German Socialist movement. The main reason why Biden and the rest of the U.S. state apparatus have refrained from banning groups like the Democratic Socialists of America is because, unlike the German Social Democrats in Imperial Germany, they do not pose a meaningful threat to U.S. Empire. Yes, this is due to the limitations of our reach, our numbers; but we are also held back by ideology and political inertia. If we are to grow our movement in the face of incredible odds, like the German Social Democrats, we must be willing to change in response to the conditions around us. But what are the ideological and political limitations holding back the U.S. Left?

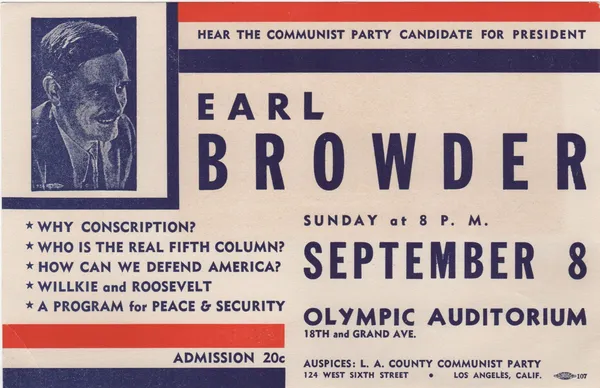

On Browderism

Decades after the period of “State Socialism” and the Anti-Socialist Laws in Germany, the United States also saw a party rising to the forefront of its working class politics. The Communist Party USA split from the Socialist Party of America much like the Communist Party of Germany split from the Social Democratic Party. In the face of the official U.S. anticommunism of the First Red Scare, the CPUSA would ultimately grow to a height of over 75,000 members by 1947 and organize incredibly impactful and wide-reaching campaigns, such as that for the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill. And yet, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the CPUSA collapsed, hemorrhaging members and finding itself riddled with FBI informants as it was targeted by the repressive hammer of the U.S. state. What on earth happened?

In truth, it was the confluence of myriad factors. No one thing can be blamed for the decline and fall of the Communist Party USA, despite what polemicists and sectarians may want to believe. But what definitely did not help the party when it desperately needed energy, support, and strength was its de-facto dissolution into the Democratic Party.

On January 7th 1944, the National Committee of the Communist Party USA voted in favor of restructuring the party into the Communist Political Association; not a political party, but a lobbying group to represent the communists on the wider stage of U.S. politics. The CPUSA’s then-chairman Earl Browder declared that “the communist organization in the United States should adjust its name to correspond more exactly to the American political tradition and its own practical political role.”[19] He was, in a sense, providing legitimacy to the U.S. political establishment and pushing for the largest organization of socialists in the country to undo itself so as to not challenge that establishment.

Let us take a step back; how did the U.S. Left reach this point, and what was Browder’s role in it? Browder, as chairman and general secretary of the CPUSA, was the primary architect of this shift and its most public face, but we should not fall into the ideological trap of individualizing a trend that emerged from the conditions of the time and the actions taken en aggregate by members of the party. However, what came to be termed, rather polemically, as “Browderism” was part of what doomed the CPUSA. It was born out of the culture of official communism of the 1930s and ‘40s, specifically the period of the “popular front” advocated by the Comintern, and of the culture of the New Deal in the United States. These were both conceptualizations of alliances between the working class and bourgeois political organizations; the popular front was an alliance between communists, socialists, and democrats against the threat of fascism, while the New Deal coalition that coalesced around FDR was an alliance between union workers, big business, progressives, African Americans, poor whites, and Dixiecrat segregationists. Although FDR’s actual economic policies were heavily in favor of big business, the CPUSA was convinced by his rhetoric and by the token involvement of organized labor.[20] During FDR’s presidency, the CPUSA, with Browder at its head, saw itself as a willing and vital ally and supporter of these dual fronts: against fascism and against poverty.

This is not to say that the CPUSA at the time was unified in a gungho support for FDR’s project. Far from it! The CPUSA remained a vocal critic of the New Deal from the Left, and agitated for welfare reform that would have been more radical than Roosevelt’s program. During the leadup to the Second World War, the CPUSA generally advocated for uninvolvement (though of course they could not have known at the time how the changing conditions of the war would have affected the world). While FDR had to contend with the reactionary Dixiecrats of his own party, the CPUSA had prominent African American members who challenged chauvinism within their own party and led the CPUSA’s campaign for self determination for the black belt. But by the time the United States entered into WWII, the CPUSA had begun to focus its energy on supporting the alliance with FDR’s Democratic Party.

Browder provided the ideological justification for this increasingly prominent trend within the CPUSA during the late 1930s and ‘40s. According to him, “Communism [was] Twentieth Century Americanism.”[21] When the United States entered into the war against the Axis, he asserted that in the post-War world, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. would engage in close cooperation, along the model outlined at the Tehran Conference of 1943, and through the United Nations as an international cooperative body.[22] Even before the Tehran Conference, however, he had become an advocate of class collaboration; his book Victory and After openly declared the need for the working class to support bourgeois leadership during the war against fascism.[23] It is no surprise then, when Browder spoke just before the National Committee voted to de facto dissolve the CPUSA, he declared that “Capitalism and Socialism have begun to find their way to peaceful coexistence and collaboration in the same world.”[22]

Thankfully, this distortion of the communist project would not last. Just as soon as the war was over, communists both in the U.S. and abroad began to critique Browder’s line on class collaboration and the coexistence and cooperation of capitalism and socialism. Jacques Duclos, leader of the French Communist Party, provided a scathing and vital denunciation of Browderism when there came advocates for liquidation in France as well. He declared that Browder’s push to dissolve the CPUSA was a “notorious revision of Marxism”, and that his ideas of collaboration between the capitalist and socialist worlds were “erroneous conclusions in no way flowing from a Marxist analysis of the situation.”[24] After Duclos’ article, Browder was stripped of leadership and, after further actions seen as going against the then reconstituted CPUSA, was expelled from the party in 1946.

This would not be the end of the discord within the Communist Party USA however. The internal conflict over Browderism was just one blow in a long line of setbacks that began with the sudden turn of platform following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939. After decades of faithless factionalism and red scare attacks, the CPUSA declined to a measly number of members. Ironically enough, despite the repudiation of Browderism in the 1940s, today the CPUSA is little more than another Left-wing group that endorses the Democratic candidate for President every four years.

Against Endless Browderism; For Independent Organizing!

Why did I feel the need to relitigate these episodes from the history of the international working-class movement? I hope that the parallels to our situation today are becoming apparent. Biden’s admittedly ambitious spending plan is comparable, in the sense of its role in national politics, to the welfare schemes of Otto von Bismarck in Imperial Germany; his justice department’s campaign of anti-extremism is the new face given to the repressive hammer brought down on radical organizing across countries and across times. But despite Bismarck’s “State Socialism” and his Anti-Socialist Laws, the SPD, incredibly, grew, and grew immensely, during this period! What allowed the German Social Democrats to grow in size, reach, and influence was their commitment to independent working-class organization that could continuously agitate against these measures. No such organization has consistently existed in the United States.

Earl Browder undid the U.S.’ largest working class organization, and for what? For the support of the bourgeoisie? Despite all that Browder may have thought about the possibilities of class collaboration, these dreams never manifested, and the United States emerged from the war not as a nation-state committed to international cooperation, but as the new capitalist imperialist hegemon.

The dissolution of the CPUSA was a major blow to independent socialist organizing in this country, and in many ways its effects still linger with us. I am not arguing that modern U.S. Leftists think the same things Browder thought, nor that there is some direct continuity with Browderism among the contemporary U.S. Left. However, despite the superficial dissimilarities, in practice many on the Left continue Browderism, sticking to the same old, same old.

Our largest organizations are already, in a sense, “Browderized.” The CPUSA, as mentioned earlier, today tails the DNC. The Democratic Socialists of America, founded as a group to lobby the Democrats for pro-working-class change and since filled to the brim with young people far more radical than Michael Harrington, remains fearful of breaking away from the Democrats. Self-identification as a Democrat or as a liberal is down within the DSA; but at the most recent convention, with the exception of some resolutions such as that for applying to the Forum of Sao Paulo and the adoption of a platform, the status quo has remained entrenched. This status quo is 21st century Browderism! If DSA maintains the trajectory it is currently on, it will be doomed to shrinking membership and even faster shrinking relevance, and it will never be able to help lead the American working class.

Eric Blanc, the constant advocate for a head-down ineffective politics, argued against a resolution to maintain DSA’s commitment to breaking away from the Democrats in an article published in August. Using high-minded words and phrases that sound ever so reasonable, Blanc asserts that, somehow, sticking with the Democrats will build working class trust in a socialist movement generally. He supports an eventual break from the DNC, but only in a vague sense. Rather than recognizing it today, he pushes it down the road, not just to tomorrow, but to some uncertain time in the future. Breaking away from the Democrats is not incompatible with building working class power. Perhaps Blanc and others in the DSA who continue to support instinctually clinging to the Democratic Party like Browderist tailists ought to read Jonah Martell’s program for Democrat addiction.

On top of this, there are some on the Left, whether in organizations like the DSA or operating primarily online, who have fallen for Biden’s reforms and his supposed opposition to fascism or authoritarianism. It is absolutely repugnant that there are people who consider themselves socialists or leftists of any sort who offered support for Biden’s abortive attempt at a color revolution in Cuba. It is shameful that there are those who consider themselves leftists who offer support, whether meaningful or otherwise, to the conflict brewing between the United States and China. Biden’s nationalist pseudo-Keynesian economic revival is pointedly aimed at combating China; there are those on the Left, whatever term they choose to self-identify with, who see opposing China as a must. No socialist should ever offer support to the imperialism of their own bourgeois government, no matter how they feel about the state being targeted. Biden is not a breath of fresh air for the working-class, and he is not an antifascist ally.

We must actively undo the petty Browderism that defines our movement and organizations today! If we are to ever even hope to do what the SPD did in the face of impossible odds, actively organize and propagandize against repression and constant undermining, we must have an independent organization that is able to do those things. The comparison to the times of Bismarck and Browder is not to say that Biden is one and the same; it is to assert that the Left has seen this before. We must learn from the past, from both the successes and the failures, if we are to build our movement, assert our counter-hegemony, and win. Unprecedented times call for unprecedented solutions; Biden and all of his bourgeois allies know this well and are putting it into effect as we speak. Will we?

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Igor Derysh, “Joe Biden to rich donors: ‘nothing would fundamentally change’ if he’s elected,” Salon, June 19, 2019, https://www.salon.com/2019/06/19/joe-biden-to-rich-donors-nothing-would-fundamentally-change-if-hes-elected/ ↩

- Tim Hains, “Bernie Sanders: ‘Absolutely’ Biden Can Still Be Most Progressive President Since FDR,” Real Clear Politics, January 21, 2021. https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2021/01/21/bernie_sanders_absolutely_biden_can_be_most_progressive_president_since_fdr.html ↩

- Lauren Gambino, “Biden’s FDR Moment? President in New Deal-like push that could cement his legacy,” The Guardian, March 6, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/mar/06/biden-new-deal-economic-infrastructure-plan-politics ↩

- Mario Tronti, “Workers and Capital,” Libcom, https://libcom.org/book/export/html/42233 ↩

- Ashley Smith, “Imperialist Keynesianism: Biden’s program for rehabilitating U.S. capitalism,” Tempest, May 18, 2021, https://www.tempestmag.org/2021/05/imperialist-keynesianism/ ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “China’s GDP grew 2.3 percent in 2020, the only major economy to see positive growth,” CGTN, February 28, 2021, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-02-28/China-s-GDP-grew-2-3-percent-in-2020-Yf4Ie5dS12/index.html ↩

- Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society (London: Verso Books, 2013), 98-99. ↩

- Joseph Biden, “Inaugural Address by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.”, The White House, January 20, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/01/20/inaugural-address-by-president-joseph-r-biden-jr/ ↩

- Ibid, ↩

- Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 1. ↩

- Edgar Feuchtwanger, Bismarck (London: Routledge, 2002), 220-221. ↩

- William H. Dawson, Bismarck and State Socialism: An Exposition of the Social and Economic Legislation of Germany since 1870 (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1891), 109-114. ↩

- Dawson, Bismarck and State Socialism, 114-116. ↩

- Dawson, Bismarck and State Socialism, 123-127. ↩

- Vernon L. Lidtke, “German Social Democracy and German State Socialism,” International Review of Social History Volume 9, No. (1964): 204. ↩

- Lidtke, “German Social Democracy and German State Socialism,” 206-209. ↩

- Adam J. Sacks, “Why the Early German Socialists Opposed the World’s First Modern Welfare State,” Jacobin, December 5, 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/12/otto-von-bismarck-germany-social-democratic-party-spd ↩

- Maurice Isserman, Which Side Were You On?: The American Communist Party During the Second World War (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1982), 188-190. ↩

- George Rawick, “A New Look at the New Deal,” Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/rawick/1958/xx/newdeal.html ↩

- Isserman, Which Side Were You On?, 9. ↩

- Isserman, Which Side Were You On?, 188. ↩

- Earl Browder, transcribed and edited by Paul Saba, “Victory— and After,” Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line. https://www.marxists.org/archive/browder/victory-and-after/index.htm ↩

- Jacques Duclos, “On the Dissolution of the Communist Party of the United States,” Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/1945/04/0400-duclos-ondissolution.pdf ↩