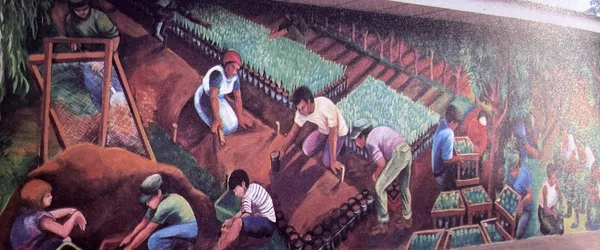

"Planting Trees" mural by Daniel Hopewell. Jalapa, Nicaragua.

I.

Over the course of its long life, capitalism, as a dynamic socio-economic system, has transformed in reaction to numerous challenges. Despite this, its numerous contradictions remain. For as much as capitalism requires a complex of flexible political and economic arrangements capable of reproducing its material conditions in even the most adverse circumstances, it also necessitates certain fixed, paradoxical social relations. One of these fundamental contradictions is centered in agriculture, specifically between those who own agriculturally productive land and those who work it. In cities, this contradiction famously matured between employers and employees, those who own their workplaces and equipment – in a word, capital – and the workers who put this capital to good use. In 1847, Friedrich Engels confidently identified factory towns as the birthplace of the working class and the frontline of the class struggle between capitalists and workers.[note]Engels, F. (1847). The Principles of Communism [HTML Version]. Retrieved from

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/11/prin-com.htm.[/note] However, regardless of where this struggle matured, regardless of when its roles solidified, the fundamental contradiction between capital and wage-labor developed long before factory owners poured the foundations for their buildings and far away from the urban centers of industrial production. Capitalism, rather, began in the countryside, where capital refined its rule. And while capitalism may have crept from country to town, exploding out of its factories in the process, its true homeland has always been, and will always be, farmlands and food sources. The prototypical form of the fundamental contradiction between owner and worker is the contradiction between the agricultural landlord and laborer. For as long as capitalism has existed, the social organization of farm and food has reproduced this contradiction, and it will continue to do so until class struggle abolishes the power of the landlords and the oppression of the workers.The end of this struggle is long overdue and more consequential than it may seem at a glance. The capitalist method of organizing agriculture developed a certain style of farming and demanded certain labor requirements. The environmental and moral hazards of industrial farming and inexpensive immigrant labor, the logical result of this system and its requirements, have been well documented. But what about the newer problems of farm and food? What about customs and institutions less than 100 years old? What about the unsustainable fast food centers that receive the cash crop food products from industrial farms? Or the overexploited and underpaid fast food workers who process them? The contradiction between agricultural landlord and laborer lurks behind every effort to unionize restaurants, behind every fight for a fair wage, behind all the poor and colonized people sweating over grills and crying behind counters. Their struggles began on farms and evolved with food. Fry cooks and fieldworkers may share a common solution too, routed through and grounded in a worker’s history of farm and food.

II.

Capitalism began in the English countryside in the 16th century. Four hundred years prior, in 1066, the King of England, Edward the Confessor, died of natural causes. His distant relative, the Duke of Normandy seized the opportunity to claim King Edward’s country as his own, and he invaded England. Over the subsequent four centuries, the Norman government centralized state power, divesting local lords of their power and armies, and deposing rebel challengers.[note]Wood, E. M. (2017). The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (pp. 98). London, England:

Verso.[/note] By the sixteenth century, the Norman government demilitarized the rural landlords. Without personal armies to enforce their rule and extract wealth from peasants, English nobility resorted to economic coercion, and the Norman government deposed enough landlords and consolidated enough of their landholdings to give those who remained inordinate and unusual economic power over the peasants who lived and farmed on their estates.[1] It was during this period that English landlords developed their own market in leases, which set rents for the tenant peasants who farmed their land. The peasants, in turn, resorted to competition in the improvement of their productive means and labor efficiency strategies in order to make rent in an increasingly unpredictable market.[2] It was in this context, the 16th century English countryside where agricultural landlords were commodifying access to land and compelling farmworkers to innovate and compete to survive, that capitalism was born.

The commodification of land in the English countryside and the subsequent competition between peasant farmworkers changed the ways in which both workers and owners thought about their rights. English landlords, as well as an emerging class of rich peasants, became increasingly preoccupied with improvement, an archaic term that referred to the technical updating of agricultural practices for the purpose of profit.[3] In the 16th and 17th centuries, improvement made farmland more profitable for landlords and made the peasant farm workers more competitive internationally. In 1690, the philosopher John Locke synthesized an idea that had been developing in the English countryside between landlords and rich peasants for decades, namely that improving land or investing money in it gave some people rights others did not have. Specifically, Locke argued that the Christian God made the world in common but made each soul its own private entity, made labor and money an extension of the soul, and anything in the world that a private person mixed with their labor or money became as much a part of the that person as their private soul, with all the God-given rights one would normally reserve for one’s self.[4] In support of landlords and rich peasants, Locke, for the first time in history, introduced the idea of private property. Before this, peasants enjoyed customs derived from the belief that some land had to be held in common; so that all could graze their livestock, collect firewood, or gather harvest leftovers at certain times of year. But in conjunction with the commodification of land in general, landlords and rich peasants also began to privatize common land in increasing quantities, as they improved it in competition with each other and for their own personal profit.[5] The enclosure of public land for private use began a tumultuous wave of violence that rocked the English countryside and carried capitalism from the country, through the towns, and beyond England’s borders.

Private property permanently split the people of the English countryside into two classes: landlords aligned with wealthy peasants and the poor peasant workers who could not afford any land whatsoever. Without land or a wage paid by a landowner, peasants had no rights. Without rights, landowners were able to evict and starve those they couldn’t employ. The displaced masses of the countryside swelled English urban centers. Between 1801 and 1844 alone, the population of Birmingham in England’s midlands increased more than 170% from 73,000 to 200,000, and during the same period, the population of Sheffield further north increased almost 140% from 46,000 to 110,000.[6]

While the flow of workers from country to town was certain, the rule of landowners over the countryside was far from guaranteed. Indignant farmworkers periodically organized mass uprisings against their oppressors. Famously, 15,000 peasant farmworkers marched on London in 1381.[note]Cooney, S. J. (1974). Social Upheaval and Social Change in England, 1381-1750 (thesis)

(pp. 15). Dissertations and Theses. PDXScholar. Retrieved 2021, from

https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3056&context=open_access_etds.[/note] Another 16,000 formed an army and raided enclosed properties in 1549.[7] To keep the peace, the English government agreed to a compromise. They would grant farmworkers rights, but farmworkers would have to go elsewhere to exercise them.

III.

Overwhelmed by the class struggle forming in both the town and country, England’s rich and powerful began sending their displaced and wage-less workers to settle foreign colonies. As early as the 1580s, England’s ruling family – the Tudors – began granting Irish farmland to English settlers willing to introduce the agrarian capitalist model to Ireland.[8] The logic of improvement that fueled the privatization of the English countryside also propelled large-scale conquest and colonization, as well as the reproduction of the enclosure process across large swaths of the globe, over the next few centuries

John Locke, theorist par excellence of the English landlords, now proposed an equally “revolutionary” justification for English colonialism. Locke argued that although North American lands might be just as fertile as an English acre, they would never be worth 1/1,000 the value of an improved plot of land. Accordingly, he reasoned that it would be wasteful and, importantly, inhumane to leave the land in the custody of its indigenous people.[9] Thus, the class of capitalists emerging out of the English countryside expanded the contradiction between landlords and farmworkers to encompass colonizers and colonized people, slavers and enslaved. As the contradiction grew to international proportions, its character changed. The expansion of English borders changed the character of English nationality. Workers had just as few rights as ever, but they had more rights than the slaves that landlords captured, bought, and sold as a captive workforce for their growing international colonies.

Slavery grew up out of the English theory of private property. The same worldview synthesized by Locke in which a person’s rights depended on their access to land or labor, also supported the development of slavery. In this worldview, a people who failed to improve their land had no inherent right to it, and without the right to their land, they lacked the rights that land and labor guaranteed, and without the rights that land and labor guaranteed, English settlers treated them the same way that they would treat the land they seized: subservient to their authority and subject to their custody and “improvement.”[note]Losurdo, D. (2014). Liberalism: A Counter-History (G. Elliott, Trans.) (pp. 24). London,

England: Verso.[/note] In the so-called New World, England’s poor peasant farmworkers became a new class of settler landlords, and slaves became a new class of exploited farmworker. By 1700, the total slave population in the Americas had reached 330,000; by 1800, it was 3 million, and by 1850, it had peaked at twice that amount.[10] The newly minted United States and its fellow colonial powers prospered on backs of millions of unpaid, oppressed, and exploited slaves. During this period, a prominent English businessman noted, “‘the n**** trade and the natural consequences resulting from it, may be justly esteemed an inexhaustible fund of wealth and naval power to this Nation.’”[11] By 1832, fully ¾ of England’s coffee, 15/16 of its cotton, 22/23 of its sugar, and 34/35 of its tobacco was a product of slave labor.[12] 200 years after the seed of capital had been laid in the agricultural heartlands of English feudalism, the English farmworker could finally claim the same rights as many men of a higher class, but only at the expense of the colonized slaves who took their place.

In the Americas – and in the United States in particular – slavery became an inestimable source of agricultural wealth. Historical records show that slavery in the United States was concentrated in regions where farmland was most valuable, farm commodities were more profitable, and landholdings the largest.[note]Wright, G. (2003). Slavery and American Agricultural History. Agricultural History, 77(4),

532. Retrieved September 28, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3744933.[/note] Slave labor, itself, could inflate farmland value in those parts of the U.S. where it persisted and farmland value increased disproportionately where landlords did not have to pay farmworkers.[13] Constrained by neither wages nor the risk of unreliable labor, landlord slave-owners farmed far larger quantities of cash crops – especially wheat – than their competitors, and used their earnings to buy more slaves and larger land holdings more quickly.[2] As a result, slave-owner landlords accumulated unprecedented wealth and power. For 32 the United States’ first 36 years, its president was a slave-owner from Virginia, where 40% of all slaves in the United States resided.[14] By the time of the U.S. Civil War, the official end of Western state-sanctioned slavery, most slaves resided on plantations with farmlands as large as 500-1,000 acres each.[note]Vejnar, R. J. (n.d.). Plantation Agriculture. Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved September

28, 2021, from http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1832.[/note] Shortly before the Civil War began, in 1860, there were 2,044,077 farms in the United States, and only 2% of these were 500 acres or larger.[note]USDA, 1940 Census of Agriculture, 65–132 (1940). Ithaca, NY; USDA Census of

Agriculture Historical Archive.[/note] Although far from the English countryside and without any official title or legal nobility, the exploitation of slave labor in English colonies concentrated the wealth and power of the United States’ farmlands in the hands of an elite few at the expense of the toiling masses.

Even after the end of the American Civil War, when the U.S. definitively abolished slavery and obliged the state to recognize farmworkers and landlords alike as entitled to equal rights regardless of class or country of origin, landlords continued to leverage their special access to land in order to exploit and oppress farmworkers. Dependent on slave labor for centuries, Southern agricultural landlords lacked the access to capital and credit they would need to compete with Northern and Western farms without a standing pool of captive labor. To deliver this, Southern landlords interfered in the Freedmen’s Bureau, among the other administrative bodies the United States government convened to transition freed Black slaves to full citizenship, sabotaging them in order to negotiate labor contracts that transformed freed slaves into sharecroppers.[15] As sharecroppers, newly “freed” farmworkers leased land from landlords and bought farm implements and seed from them on credit, obliged to reside on their rented plot until they paid up their leases and loans with interest.[note]Grubbs, D. H. (2017). Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers' Union and the

New Deal (pp. 7). Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press.[/note] Suffice it to say, sharecroppers rarely, if ever, earned enough to pay what was due. Debt and rent were as good as chains to the new U.S.American tenant farmworker.

IV.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the disparity between landlord and tenant farmworker was as wide as ever. By 1900, more than half of all Southern farmers were non-owners, tenants, or sharecroppers, mostly Black, totally humiliated, and unimaginably poor, and the people who owned the land were largely, if not entirely, white and wealthy.[note]Hurt, R. D. (2002). Problems of Plenty: The American farmer in the Twentieth Century (pp.

5). Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee.[/note] 75% of all Black farmers in the South were tenant farmworkers living barely above starvation levels.[16] Testifying to their miserable condition, one journalist wrote, “tenant houses are incomparably the worst I have ever seen used for human habitation.”[17] Their landlords fared far better. While their tenants starved, agricultural landlords in Arkansas alone earned as much as $10,744 per year.[18] Adjusted for inflation, that would be nearly a quarter-million dollars in 2021.[note]U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). CPI Inflation Calculator. U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics. Retrieved 2021, from https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.[/note] Their largest expense was labor, for which they only re-invested a little more than 10% of their earnings.[19] Landlord fortunes surged again in the 1910s. Agricultural prices rose in the United States when World War I began in 1914, and they rose again when the U.S. entered the war in 1917.[20] Between 1909 and 1919, the total U.S. agricultural income increased from nearly $7.5 billion per year to $17.7 billion.[21] As the 20th century continued, Black and brown farmworkers may have had legal rights, but they were political and economic non-entities. The Civil War was not a war to end capitalism, nor to reconcile its fundamental contradictions. It was a war fought between two competing visions about its future. The landlords were bound to win either way; and win they did. Their fortunes and the future of the economic and social relations that upheld their privileged position seemed unimpeachable until something completely unexpected happened. The market collapsed.

The steep decline in agricultural prices in the United States at the end of the First World War began a chain reaction of economic unrest that no one could have foreseen. When the war ended, demand for a constant steady stream of food ended with it, and the end of this demand crashed the value of agricultural commodities. The price of corn dropped 78%, wheat 67%, cotton 57%, and livestock 32%.[22] Meanwhile, operating expenses remained constant and prices for the commodities that neither landlords nor farmworkers could produce remained high.[23] An agricultural recession began in which a half-million farmers declared bankruptcy and 17 in every 1,000 farms foreclosed within 10 years.[24] This partial collapse of the agricultural economy precipitated a much broader collapse of the global economy and, amid other disasters, contributed to the Great Depression which began in 1929.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt quickly and decisively crafted legislation to revive the moribund U.S. economy. He called this legislation the New Deal, a significant portion of which delegated aid to the nation’s agricultural economy.[25] Unsurprisingly, Roosevelt’s legislators wrote the New Deal legislation with agricultural landlords in mind. This legislation created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) within the USDA. The AAA paid landlords to destroy surpluses in wheat, cotton, corn, rice, tobacco, hogs, and dairy to stabilize prices, then authorized them to sell the remainder in the open market for profit.[26] For each acre destroyed on a sharecropper plantation, the government paid landlords in full, including the 50-75% that tenant farmworkers usually kept for themselves in addition to the rent they usually paid.[27] In the immediate aftermath of this legislation, landlord income nearly doubled, and tenant income slightly decreased.[2] Unable to take any more, the United States’ tenant farmworkers revolted.

Southern farmworkers unionized. In Arkansas, two white socialists named Henry Clay East and H.L. Mitchell organized farmworkers into an extremely militant union named the Southern Tenant Farmworkers’ Union (STFU), which was first established in 1934.[28] Notably, the STFU was integrated. Although tenant farmworkers were mostly freed slaves, their families, and their descendants, at least 33% of all white farmers in the South were also tenant farmworkers[29] At its first ever meeting, attendees agreed that farmworkers facing the same problems should not be divided by race, and all the union’s subsequent mass meetings and central leadership committees were integrated.[30] At various times, the STFU demanded racial equity, a living wage, enforced child labor laws, enforced compensation for farmworkers who improved land, the abolition of poll taxes, the abolition of prison labor, a bill of workers’ rights to include free speech and the right to assemble as a union, and the wholesale reorganization of large plantations into cooperative farms.[31] Landlords staunchly opposed such concessions. The organized tenant farmworkers’ demands added up to little more than dignity and the same rights as workers in other industries.

In the 1930s, agricultural unions posed an unprecedented challenge to landlord authority, which landlords met with utter brutality. No one was safe. In Arkansas, landlords unleashed mercenaries on the STFU’s membership. Individuals were beaten, shot, and jailed. Some even had their homes destroyed[32] Farmworkers couldn’t even depend on safety in numbers. In January 1936, landlords sent police officers and mercenaries to an assembly of over 400 sharecroppers near Parkin, Arkansas where they beat men, women, and children with axe handles and pistol butts.[33]

After the STFU voted to strike in 1936, Arkansas landlords mobilized local police and the national guard to intimidate them. The former stalked known union members, while the latter assembled machine guns and military bases at strategic crossroads.[34] In one particularly heinous instance, during the 1936 strike, police officers arrested two Black tenant farmworkers named Josh Turner and Nathaniel Smith at their homes. The men were abducted and beaten mercilessly for a day. Then, they were interrogated for information regarding strike leaders, and after the two men refused, the police illegally detained them for weeks, searched their homes without a warrant, and confiscated their firearms. The police officers fabricated a story that the two men fired guns into a crowd in order to start a riot during the strike. The police eventually released Turner and Smith when their story came to light, but only after forcibly coercing the men to plead guilty in order to protect the police force from lawsuits.[35] Against an utterly unified opposition armed with all the state’s repressive apparatuses, and with too little money and security, the STFU collapsed in 1937 and officially disbanded in 1939.[36] The AAA’s incentive to destroy farmland had already displaced as much as 20% of the South’s tenant farmworker population in the first few years of the 1930s.[37] The brutality of the agricultural landlords that followed displaced many more, and the Black former tenant farmworkers constituted a “Great Migration” to Northern urban centers in search of work and peace. Many would never return. In 1920, 14% of all farmers in the United States were Black, but by 2003, that number had declined to just 1%.[note]Ficara, J. F., & Williams, J. (2005, February 22). 'Black Farmers in America'. NPR.

Retrieved 2021, from https://www.npr.org/2005/02/22/5228987/black-farmers-in-america.[/note]

V.

In the same year that the STFU collapsed, the family of future California-based farmworker organizer Cesar Chavez, then 10-years-old, was forced to forfeit their Arizona farmland by the turmoil of the Great Depression, and move to California with the intent of living off of temporary farm work, a situation that soon became permanent.[38] In 1939 – the same year that the STFU officially disbanded – the agricultural union movement continued. That year, Chavez’ father, Librado Chavez, helped organize a union in the dried fruit industry.[39] Although landlords broke his strikes and dismantled his union, Librado’s daring and righteousness left a lasting impression on his son. Chavez would go on to develop the National Farm Workers Association in 1962 with Dolores Huerta, an organization he would eventually lead.[40] The National Farm Workers Association’s first program included a minimum wage of $1.50 per hour for farmworkers, the right to unemployment insurance, the right to collective bargaining, a community credit union, and a hiring hall.[10] Chavez succeeded where others failed and for the first time in the United States’ history – and possibly the centuries’ long history of capitalism – presided over a farmworker movement that put an admittedly slight but permanent check on landlord power.

Chavez’ movement surged in a series of strikes, protests, and marches between the 1960s and 1970s. He organized and mobilized as many as 10,000 farmworkers, striking farmlands and protesting landlords in support of demands that went beyond a living wage, work, and collective bargaining, including health care and protections against the dangerous farm implements and new industrial chemicals popular on farms after the 1950s.[41] Striking farmworkers rallied around images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and carried both Mexican and U.S. flags. The explicit cultural and ethnic solidarity that prior farmworker movements lacked wed the farmworkers of Chavez’ movement to a liberation struggle that sustained individual energy and commitment where a purely economic struggle could not.[42]

Like their forerunners in the South, California’s agricultural landlords met Chavez’ challenges with brutality. Hired guards patrolled ranches with shotguns, beat up strikers with baseball bats, drove vehicles through picket lines, attacked men and women, shot at striking farmworkers, and bombed a union office in a dynamite attack.[32] In 1971, the Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms discovered that California landlords had hired a drug dealer to assassinate Chavez for $25,000.[43] They intercepted the hitman before he could harm Chavez but never successfully investigated the assassination or arrested any suspects. Other farmworkers would not be so lucky. Deadly street fights broke out in the 1970s. In August 1973, landlord-sponsored mercenaries beat up and killed a 24-year-old striker from Yemen named Nagi Daifullah, and two days later, another mercenary shot and killed a 60-year-old striker named Juan de la Cruz.[44] In February 1979, ranch guards shot and killed 20-year-old Rufino Contreras.[45]

In a particularly egregious case in September 1983, landlord-sponsored mercenaries shot and killed a 19-year-old union organizer named Rene Lopez at his workplace, the Sikkema Dairy Farm, outside Fresno, California.[46] During a strike, two mercenaries drove past Lopez at the picket line and were seen entering the owner Fred Sikkema’s office. After a meeting, they drove back past Lopez and deliberately shot him in the head. Only the gunman would be charged and convicted for murder.[47]

Unlike his predecessors’ organizations, Chavez’ movement withstood the violence of California landlords. The union that his organization became, the United Farmworkers of America, still exists and organizes farmworkers across the United States.

Despite some successes, the scope of Chavez’ imagination limited what he accomplished. He sought reform before he sought revolution, and the landlord dominated government with whom he agreed to work successfully curtailed his most ambitious demands. With the support of Chavez-ally and liberal governor Jerry Brown, California’s state legislature passed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) in 1975. This legislation protected California farmworkers’ rights to organize unions, boycott, and utilize secret ballots in union elections.[33] In the same stroke that Chavez successfully persuaded California’s government to pass this legislation, landlords successfully persuaded the California legislature to drain its funding. Without funds for prosecutors to litigate legal violations, landlords did as they pleased.[48] In 1982, Republican George Deukmejian became governor of California and further sabotaged the ALRA. Deukmejian amassed over one million dollars in donations from agricultural landlords, and in return, he packed the already dysfunctional and underfunded Agricultural Relations Board with landlord-backed bureaucrats willing to overlook all but their most severe transgressions.[5]

Government inaction allowed the perpetuation of the exploitation and oppression of farmworkers. As late as 1985, media discovered a 300-acre strawberry farm in California operated by a landlord named Jose Ballin on which farmworkers lived in the same slave-like conditions from which Chavez and his forerunners sought to liberate the toiling masses of the countryside. These farmworkers not only lived in holes dug into hills, old tractors, and cardboard shacks, but drew their water from an irrigation pipe and used a eucalyptus grove as a latrine.[49] Like the Southern tenant farmworkers that preceded them, Ballin’s farmworkers paid rent despite their inhumane and undignified living conditions: $0.25 per hour while not working.[2] After Chavez, progress for oppressed people stalled in the countryside. The dissipation of their mass movements mirrored similar social movements in urban centers. The white hot summers of the riotous 1960s and 1970s cooled in the uneasy 1980s and 1990s. Neither oppression and exploitation nor the indignation of oppressed and exploited people ended. The oppressors and exploiters simply discovered better ways to contain the explosive powers of the masses. Surprisingly, food may have had a central role in containing them.

VI.

The Black communities concentrated in the United States’ urban centers – communities that partially consisted of the freed slaves, their families, and their descendants displaced by Southern landlords in the 1930s – revolted in the 1960s and 1970s, and the government used agriculture and its products to subdue them. At the time, police brutality and widening economic, social, and political disparities between white communities and Black communities built the pressure that exploded into urban riots.[50] Despite the 1964 Civil Rights Act, by 1968, the average Black family earned only 59% as much as the average white family.[51] As national unemployment rates fell across the country from 7 to 4% through the 1960s, they remained high in Black communities. In Watts, the site of the eponymous riots, unemployment fell only from 11 to 10% in the same period.[2] At least 300 such riots occurred between 1965 and 1968, 176 of them in the summer of 1967 alone[35] President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration concluded that access to economic opportunities could solve the problems that caused the riots.[52] Meanwhile, the United States’ agricultural economy never actually recovered from its slump after the First World War. It limped along for decades dependent on the support of the U.S. government. Johnson’s administration determined that access to economic opportunities could likewise resolve discontent in the countryside, and in 1965, LBJ signed the Food and Agriculture Act, which promoted the cultivation of cash crops like soy, corn, and wheat.[53] The confluence of cheap and accessible cash crops and small business opportunities in urban centers buoyed by government support drew fast food franchises from the suburbs to the cities and trapped its largely Black and brown indignant masses within them.

To accomplish this objective, fast food took advantage of cheap goods from farms and the inexpensive credit from government small business programs. Excess soy, corn, and wheat from the countryside became the oils, emulsifiers, proteins, sweeteners, and livestock feed that were the foundation of inexpensive fast-food products like sodas, corn-fed beef patties, artificially preserved products, and fried food.[54] Operating as franchise chains rather than corporations helped the fast-food industry take advantage of loopholes in government funding meant for small businesses.[55] In 1970, the United States government granted individual fast food franchises hundreds of thousands of dollars in subsidized loans to promote business in Black urban communities.[56] Programs such as the Commerce Department’s “Project Own,” which disbursed $40 million in 1968 to kickstart 10,000 minority-owned businesses by 1969 and 20,000 by 1970, infused millions of dollars into the fast-food industry as it expanded into urban centers.[52] By 1979, the Commerce Department’s Equal Opportunity Loan Program infused another several million dollars into the fast-food industry, which continued to rapidly expand after the 1960s.[57]

The spread of fast-food franchises within U.S. cities exposed the urban workforce to new and terrible working conditions. McDonald’s alone grew from a few hundred locations to nearly 14,000 by 2021.[note]Topic: McDonald's. Statista. (n.d.). Retrieved 2021, from

https://www.statista.com/topics/1444/mcdonalds/.[/note] By 2020, more than one in three of the fast-food workers who staffed these thousands of locations identified as non-white.[note]Rho, H. J., Brown, H., & Fremstad, S. (n.d.). A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers inFrontline Industries. CEPR.net. Retrieved 2021, from https://axelkra.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020-04-Frontline-Workers.pdf.[/note] The economic opportunity that President Lyndon B. Johnson envisioned for these workers never materialized. By 2013, one in five families with a member in the fast-food industry had an income below the poverty line, and 43% had an income two times the federal poverty level or less.[note]Allegretto, S., Doussard, M., Graham-Squire, D., Jacobs, K., Thompson, D., & Thompson,

J. (2020, December 22). Fast Food, Poverty Wages: The Public Cost of Low-wage Jobs

in the Fast-Food Industry. UC Berkeley Labor Center. Retrieved 2021, from

https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/fast-food-poverty-wages-the-public-cost-of-low-wage-jobs-in-the-fast-food-industry/.[/note] More than half of all families with a member in the fast-food industry who worked full time benefited from a public welfare program.[2] To make matters worse, by 2014, nearly 90% of all fast-food workers alleged some form of wage theft.[note]Hsu, T. (2014, April 1). Nearly 90% of Fast-food Workers Allege Wage Theft, Survey

Finds. The LA Times. Retrieved 2021, from

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-mo-wage-theft-survey-fast-food-20140331-story.html%3f_amp=true.[/note] Overworked and underpaid already, 87% of fast-food workers struggled to afford benefits like health care and necessities like rent.[58] In June 1968, the United States’ Commerce Department convened a conference in New York called “Managing for a Better America: Mobilization of Management in the Attack on Urban Despair and Decay.” Here, the president of Dunkin’ Donuts asserted that through fast-food franchise ownership and employment, Black Americans could become, “integrated into American society,” by undergoing, “a radical change – a change in values, a change in the educational opportunities he set up for himself and his family, and in the responsibility he showed for his community.”[59] The uprisings in the urban centers subsided but not because fast food changed anything about Black American values. Among other factors, fast food contributed to the burnout of Black and brown revolutionaries. To this day, it sequesters the revolutionary zeal of a broad base of exploited and oppressed people.

VII.

Farmworkers and fast-food workers alike have rights, albeit the younger industry of the towns has fewer protections for its workers than the centuries old industry of the country. Farmworkers have the right to a minimum wage, child labor protections, and clearly and explicitly explained labor contracts. In some states they have the right to unionize. Fast food workers have the right to little more than a minimum wage and overtime. In the best-case scenario, workers in either industry may be able to win the right to wages adjusted for inflation, health care, education, and workplace protections for unionized workers with a militant strategy of strikes, boycotts, and other organizational tactics. However, the entrenched landlords and business owners will always have the power and money they need to reclaim concessions given to workers when conflict forces them to compromise to preserve their privileges.

The weal and woe of fast-food workers may yet resemble that of their forerunners on farms. Despite decades of setbacks and defeats, it’s always possible that a particularly driven leader or a particularly lucky movement may succeed in ways where others failed. However, the same can be said of landlords and business owners. Whatever they lose in a worker’s insurgency, so long as they remain in their powerful positions, they can reclaim in a counterinsurgency. It happened in England’s colonies: landlords replaced farmworkers with slaves. It happened on the subsequent plantations: landlords replaced slavery with sharecropping. It happened in California: landlords gutted the legislative reforms for farmworker protections. It happened before and it can always happen again, unless the workers of farm and food unite and eliminate the persistent contradiction that enables its happening: the contradiction between the landlords who own land and the workers who work it.

To this end, the workers of farm and food need a militant revolution in the countryside. Large landholdings should be broken up into parcels of 1,000 acres, subdivided again into 250-acre plots, and redistributed as cooperatives to the people who work the land. The cooperatives redistributed to the workers should be allotted high quality schools, health clinics, cafeterias, and housing, along with the right of farmworkers to use them for free. If not already citizens, cooperative farmworkers should have a clear and expedient path to citizenship. The cooperative farmworkers should be entitled to a living wage for their work on their farms. Finally, decisions about what to plant and grow should be determined by people’s needs rather than profit. This would entail the substitution of cash crops for other foods. The elimination of cash crops in the country would upset the fast-food industry in the cities. Many would close. The industry may disappear entirely. Regardless, it would free the revolutionary zeal locked up in fast food workers who may by then have the capacity to revolt and reorganize their own industry. They too deserve a living wage, ownership over their workplace, a right to good health, education, secure housing, and a union. The only people in their way are the landlords and business owners, and although mighty, they are few. Fortunately, the world these powerful few built up around themselves is far from fixed and can just as easily be undone. The workers of farm and food in the United States should follow the example of a few fast-food workers at a Burger King in Lincoln, Nebraska. Under the usual pressures of the industry plus those of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, the workers agreed with each other that what they were doing wasn’t worth doing anymore. In July 2021, they simply walked out, and on their store’s marquee, they wrote, “We all quit. Sorry for the inconvenience.”[60]

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Ibid, 100. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid, 106. ↩

- Ibid, 119. ↩

- Ibid, 107. ↩

- Rocker, R. (1989). Anarcho-syndicalism (pp. 36). Sterling, VA: Pluto Press. ↩

- Ibid, 41. ↩

- Wood, 153. ↩

- Ibid, 157. ↩

- Ibid, 35. ↩

- Ibid, 14. ↩

- Ibid, 13. ↩

- Ibid, 545. ↩

- Losurdo, 12. ↩

- Jou, C. (2017). Supersizing Urban America: How Inner Cities Got Fast Food with Government Help (pp. 92) [Kindle iOS Version]. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 2020, from https://www.amazon.com/Supersizing-Urban-America-Cities-Government-ebook/dp/B06WWRPB8Q/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1632775583&sr=8-3. ↩

- Ibid, 6. ↩

- Grubbs, 5. ↩

- Ibid, 12. ↩

- Grubbs, 12 ↩

- Hurt, 36. ↩

- Ibid, 37. ↩

- Ibid, 43. ↩

- Ibid, 44. ↩

- Ibid, 45. ↩

- Grubbs, 17. ↩

- Hurt, 69. ↩

- Grubbs, 20. ↩

- Ibid, 27. ↩

- Hurt, 6. ↩

- Grubbs, 67. ↩

- Ibid, 121. ↩

- Ibid, 73. ↩

- Ibid, 91. ↩

- Ibid, 103. ↩

- Ibid, 105. ↩

- Ibid, 184. ↩

- Ibid, 25. ↩

- Bruns, R. (2005). Cesar Chavez: A Biography (pp. 4). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ↩

- Ibid, 7. ↩

- Ibid, 34. ↩

- Ibid, 72. ↩

- Ibid, 49. ↩

- Ibid, 80. ↩

- Ibid, 83. ↩

- Ibid, 102. ↩

- Ibid, 110. ↩

- Ibid, 111. ↩

- Ibid, 96. ↩

- Ibid, 113. ↩

- Jou, 107. ↩

- Ibid, 108. ↩

- Ibid, 117. ↩

- Hurt, 133. ↩

- Jou, 33. ↩

- Ibid, 79. ↩

- Ibid, 128. ↩

- Ibid, 245. ↩

- Allegretto, et al. ↩

- Jou, 128. ↩

- https://abc13.com/lincoln-nebraska-sign-burger-king-rachael-flores-workers-quit/10882090/. ↩