“Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun."[1]-Mao

“The basic question of every revolution is that of state power.”[2]

-Lenin

Introduction

Cosmopod, the podcast for Cosmonaut magazine, recently released an episode titled Voices from the Bolivarian Revolution: Communes and the Transition to Socialism with Cris and Cira. It is an insightful episode, providing the listener with a nuanced firsthand account of the Bolivarian Revolution, its progress, its setbacks, and its current direction. Both guests are clearly knowledgeable individuals, and I highly suggest listening to the episode before or after reading this article.

The episode covers a wide range of subjects regarding contemporary Venezuela, from the ascent of the Chavista movement, the 2002 coup, the official turn towards socialism, the role of oil in Venezuelan society, the rise and role of the communes, and more.

In this article, I will be focusing on the Venezuelan Communes and will provide my reasoning as to why they do not, as they were formed and in their current state, constitute Dual Power in relation to the Venezuelan State. My purpose here is to further our collective revolutionary knowledge for the struggle to overthrow world capitalism and the construction of socialism. A key part of that struggle will be that of conquering State power.

The struggle for State power, the fundamental question of every revolution, will inevitably enter a stage of Dual Power where the working class is on the brink of political supremacy without having yet overthrown the capitalists: it will be the point where the revolution is made or broken. This is why understanding Dual Power is of paramount importance.

Context

At one point of the episode, the host and guests started conversing about the relationship between the current Venezuelan State and the Communes that arose in the context of the Bolivarian Revolution. Firstly, Cris starts talking about Lenin’s The State and Revolution:

State and Revolution by Lenin, which seems almost like a perfect book, it seems like the perfect manual to explain popular relationships and the relationship to the state, but that is not the case. If you begin to read the book over and over again, you’ll begin see that it leaves open a lot of questions particularly related to temporality. Lenin seems to think there is a point of inflexion which is when you take power, and then the working class is in power, but it’s not clear if it only has state power or reconstitutes itself as a worker’s state… A marvelous book which seems to have for many people to hold all the answers, it in fact leaves open many questions about what a long relation of coexistence between popular power and the residues of a bourgeois state, which needs, as Marx and Engels would say, to wither, but precisely when is the question, when and through what mechanisms. (Around the 01:09:00 mark).

Cira proceeds to talk about an existing situation of Dual Power in Venezuela between the Communes and the State.

There is this whole debate about Dual Power, and it seems that in the Marxist tradition the hypothesis that Dual Power cannot last, because it’s basically a situation in which on the one hand there is popular power which aims to finish with the current society, capitalist society, and then on the other hand you have the bourgeois power which has its representatives in the state. So, this situation of dual power in principle cannot last. But in truth many of the communes have lasted in a situation of dual power in Venezuela for say, 10, 12 or even almost 15 years some of them. So, in the moments when the process was really blooming, the relationship between the State and the Communes was a relation of tension, yes, but also cooperation, cooperation and tension. That was a creative tension that was very productive in the Bolivarian process, but the State hasn’t been fully reformed so there’s all these complexities about making a revolution….but at the same time, we recognize that there was this productive relationship of tension and cooperation that lead to the growth of several communes in the early days of the communal project”. (Around the 01:10:08 mark)[3]

This section of the episode is what I will be focusing on, particularly on the question of if the Commune-State relationship in Venezuela can be considered one of Dual Power or not.

Dual Power and the Russian Revolution

To begin this discussion on Dual Power, we must analyze its most famous manifestation: the Dual Power situation between the Soviets and the Provisional Government in the Russian Revolution of 1917.

In February of 1917 (O.S.), the Petrograd masses overthrew the Tsar, and in the ashes of the old regime arose two new ones: the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet. Soviets would then go on to spring up all over the Russian Empire, representing millions of workers, soldiers, and peasants. These two political institutions would exist independent of each other, in one form or another, until the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government and handed all power to the Soviets in the October Revolution.

When Dual Power arose in Russia, Lenin was quick to grasp the importance of this new situation and what it meant for the further development of the revolution unfolding before his eyes. Here arose two governments, one of the bourgeoisie and one of the masses. He went on to characterize the Soviet as “a revolutionary dictatorship, i.e., a power directly based on revolutionary seizure, on the direct initiative of the people from below, and not on a law enacted by a centralized state power”.[4] This is an important point to keep in mind: Dual Power rises in a revolutionary context, with the popular seizure of power, where neither of the institutions contending is formally subordinate to the other. They are independent and act in that way, independently cooperating or independently clashing. The independence of the institutions from each other is of the utmost importance when it comes to understanding Dual Power. In 1917, neither was subordinate to the other, which can be seen by the contradictions in orders that came from them. On multiple occasions, the Provisional Government would try to give an order that would contradict the wishes of the Soviet, in which case, the order would fall flat, since the workers and soldiers followed the Soviet above all else. Why could the Soviet defy the Provisional Government and get away with it? Because the soldiers and the workers were with the Soviet, even if the official leaders of the Soviet kneeled before the Provisional Government. The masses relied on the Soviet as its main authority and backed it up with their rifles, while they merely tolerated and distrusted the bourgeois government.

Lenin understood the Soviets as the same type of political institution as the famed Paris Commune of 1871, arguing that what distinguished these revolutionary governments from all others in history was:

- The Paris Commune and the Soviets were independent, their power an outgrowth of the direct revolutionary seizure of political power by the people.

- They both replaced the army and the police with the arming of the whole people, the workers and peasants.

- The elected deputies of the people are immediately recallable by the people and have a working person’s wage: they are workers in service to the people, not officials who lord over them.[4]

It is of interest to note Lenin’s overview of the situation when some of the Menshevik and SR soviet leaders entered into coalition as ministers of the Provisional Government. Lenin spoke out in Pravda denouncing this coalition while maintaining a firm stance that “Dual power still remains. The government of the capitalists remains a government of the capitalists, despite the appended tag of Narodniks and Mensheviks in a minority capacity. The Soviets remain the organization of the majority.”[5] Even if the leaderships were amicable between themselves and individual members entered into a coalition within the bourgeois government as ministers, there remained a situation of unstable and tense Dual Power which could only be resolved by the conquest of one over the other, as the future development of 1917 (and the subsequent Civil War) would show.

Trotsky on Dual Power

This phenomenon, that of Dual Power, as we shall see, was not new in 1917, but is in fact a reality of every past, present, and future revolutionary process, and which is elaborated on in great detail in Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, in a chapter dedicated to providing an explanation of what Dual Power is.

He starts out by calling Dual Power a “social crisis”.[6] It must be drilled in that Dual Power is not a sustainable or even particularly desirable social situation and that by its very nature it is unstable. “The splitting of sovereignty foretells nothing less than civil war”[7] (the English translation of dvoevlastie might as well be Double Sovereignty). Double Sovereignty is the product of a rising class, not yet having taken full direction oversociety, and an already spent and decrepit one, not having yet lost State power.

In the course of a revolution, which can last years, Dual Power is not a stable phenomenon, and the resolution of a situation of Dual Power can in fact open up a new period with a different type of Dual Power. In the Russian Revolution, prior to the overthrow of the Tsar, bourgeois circles around and outside the Duma grew into a type of Dual Power which stepped in to take the reins of State when the masses overthrew the Romanovs. Immediately, the Soviets were elevated by the masses, and came into conflict with the Provisional Government. When this one was overthrown by the Bolshevik Soviets, that particular period of Dual Power ended, but in the process, it opened up a new one, one of open civil war between the Soviet Power and everyone else. Dual Power wouldn’t disappear until the end of the Civil War. “When the old régime is thrown out of equilibrium, a new correlation of forces can be established only as the result of a trial by battle. That is revolution”.[8]

For more examples of Dual Power as it appeared in other revolutions, we can use Trotsky’s analysis of the French revolution, as well as pointing out some iterations from more recent times.

The French Revolution, lasting many years, provides us with consecutive examples of Dual Power. The first would be the Dual Power relation between the Constituent Assembly and the King, a relation that ends with the founding of the Republic. Dual Power opens up again with the emergence of the Paris districts, as they take over the Commune and confront the Legislative Assembly and the Convention, the people against the bourgeoisie. “The districts of Paris, bastards of the revolution, began to live a life of their own”.[9] And so turns the wheel of revolution.

Another, more recent, incarnation of Dual Power can be seen in the Cuban Revolution. Dual Power arose there through the growth and strengthening of the revolutionary army as it transformed from a small and ragged guerrilla force into the vanguard of the revolutionary masses and made its way towards La Habana, pushing its way to supremacy and forcing Batista to flee. Similarly, the Zapatista rebellion expelled the Mexican state from the territory it controlled and forced the government to sit at the bargaining table and listen to the demands of the Zapatista revolutionaries.

To synthesize our analysis of Dual Power, let us conclude the following:

- Principally and most importantly, Dual Power entails the splitting of the sovereignty between two incompatible and separate governments, independent institutions where neither is subordinate to the other. Each one represents a class; one in the process of being overthrown but still holding on to power and the other class rising without yet having achieved total supremacy.

- It is unstable, since for a society to function it needs a political center of power, a center that guides society and has a hegemonic hold on politics and violence. By the splitting of this center, civil war is assured.

- Dual Power can only be resolved by the crushing of one of the powers by the other, the result of which depends on the correlation of forces between the contending classes.

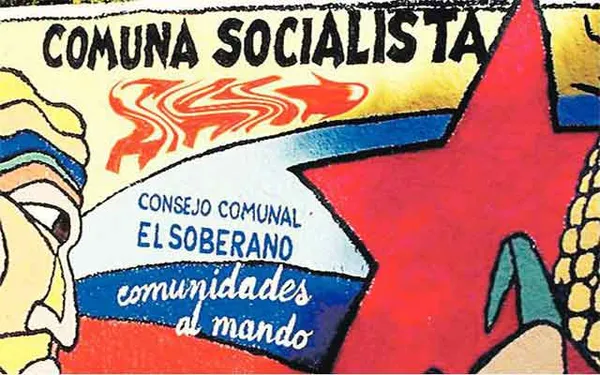

The role of the communes in Venezuela

Since we have now elaborated on what Dual Power is, we shall now proceed to see if a situation of Dual Power actually exists in Venezuela.

Let us start out by stating that Cris and Cira have a wrong conception of what Dual Power is. This is clear listening to their statements of the contemporary situation in Venezuela. They claim that Dual Power has existed in Venezuela, “in some cases” for up to 15 years. They make this claim because they believe that the current Communes in Venezuela constitute Dual Power.

There are a few reasons why these statements of theirs are wrong.

For starters, who are the contenders in this supposed Dual Power situation in Venezuela? It would seem, from the context quoted above, that they claim that a situation of Dual Power exists between the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and the Communes. They claim that since the Communes began to arise, they constituted an element of Dual Power against the Venezuelan state, which even though it has been reformed by the Bolivarian process, has not stopped being a bourgeois state.

The main problem with this line of thinking is that the Venezuelan Communes are not independent political entities. They are enshrined and are subject to Venezuelan Law. The Communes exist because the state allows and wants them to, the same as a municipality. This is drastically different to the Soviet-Provisional Government relation, where the Provisional Government couldn’t do a thing against the soviets unless the Menshevik and SR leaderships allowed it to. This fact by itself is enough to answer the question of if there is Dual Power in Venezuela with a clear and concise no, but nevertheless let us develop it more deeply.

The main Law that directs the functioning of the communes is the Ley Orgánica de las Comunas. Within the text of the law, one can see the striking contradictions between the wish to build up popular power through a communal model and having that model completely subordinate to the State. Within the very first paragraph of the law, it is stated that the communes will function within the framework of the democratic, social rights and justice State,[10] that is to say, the communes can operate only within the framework of the state. In their current form, the communes are not and cannot enter into a Dual Power struggle because they are organs of the state and operate within it.

In the book Cambiar el Mundo Desde Arriba, Machado and Zibechi make some important points regarding the political nature of the Communes. They point out that popular power arises from an organized and armed people, not from the existence of social property, as claimed in the Ley. They also note that popular power is by its nature not subject to existing constitutions or laws, which makes the Ley a self-contradicting text.

What the communes are is just another state institution. The communes have no power, as they do not possess any armed forces that allow them to carry out their will independent of the State, much less confront it. In the Venezuelan case, in contrast to the Soviets in Russia, the communes have been created from above, which means they are subject to that above which created them.[11]

To wrap up our analysis of the Venezuelan Communes, let us lay out the following:

- The Communes are institutions that exist to carry out policies and socio-economic programs within the framework of the State. They were created from above with that purpose, even if they have popular support and active participation from below.

- They are initiatives that exist with the explicit consent of the State, by its laws and Constitution. They are restricted by these, which means they are not independent.

- They do not have political power because they do not have an armed force to carry out their will independently from the State.

As we can see, the Communes, as they were created and in their current state, do not constitute a force in a Dual Power dynamic against the Venezuelan State. They are not independent entities conquered by revolutionary seizure, but State sanctioned institutions that operate within bourgeois legality.

Conclusion

Every revolution is full of contradictions, it can be no other way when the masses enter the historical stage to impose their will to do away with the old order; the construction of a new society is no simple and straightforward process. A revolution must be taken as a whole and dissected in order to see the social forces within, only this allows us to truly understand it. This is what we must do with the Bolivarian Revolution. The masses, on various occasions, rose up against the bourgeoisie, and at the same time, Chavez was carried by the people on their shoulders into the presidency through the formal bourgeois electoral process, incorporating the mass movement into the bourgeois state.

This is what allows us to say that the Communes are a product of a contradictory revolutionary process, a product of the revolutionary ascent of the masses and the diversion of popular struggle through bourgeois institutions. The revolutionary energy of the masses is channeled into institutions that on the one hand proclaim they are organs of popular power, while at the same time holding no actual power and being completely subject to the State, functioning to administer its affairs on the local level, albeit in a more directly democratic manner than your run-of-the-mill municipality.

It is for this reason that there is not a situation of Dual Power in Venezuela. The Communes cannot constitute themselves as organs of Dual Power as long as they are institutions subservient to the State. But that does not mean that they can’t potentially develop into institutions of Dual Power in the future. History is ever-changing and there is nothing to say that the further development of the Bolivarian Revolution won’t also change the character and function of the Communes. It is completely plausible that the Communes could be internally transformed and break with the State due to a social crisis and popular upheaval, in the process arming themselves and inaugurating an actual situation of Dual Power in which they could challenge and overthrow the existing State.

Understanding Dual Power allows revolutionaries to better grasp the revolutionary situations that present themselves before them. A weak understanding of the correlation of class forces, and subsequently of Dual Power, can lead a revolutionary party to misjudge the situation and make a failed attempt at political supremacy, which can lead to their ruin. A solid understanding of an unfolding revolutionary situation, on the other hand, provides the revolutionary party an invaluable tool that allows it to better lay out the path they will walk on in said revolution. History provides us with the example of Lenin, who was a master at understanding a revolutionary situation. Only the correct analysis of events permitted the Bolsheviks to build up their forces and not assault State Power before the conditions were ripe. An attempt at overthrowing the Provisional Government when the conditions were unripe would have been the ruin of the revolution. For this reason is that I write this article, to provide revolutionaries with a clearer vision of what Dual Power is, so that they can understand it and act in accord with their own correct analysis when it arises before them.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Mao, Z. (1938). Problems of War and Strategy. Access at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/works/red-book/ch05.htm ↩

- Lenin, V. (28, April 1917). The Dual Power. Pravda. Accessed at:https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/apr/09.htm ↩

- Both transcriptions were elaborated by me and are not perfect. Ellipses skip parts that I considered unimportant for the purpose of this article. Bold is my own and will be the part we will be concentrating on. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Lenin, V. (20, May 1917). Has Dual Power Disappeared. Pravda. Accessed at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/may/20.htm ↩

- Trotsky, Leon. (1930). History of the Russian Revolution. Chicago: Haymarket Books; p. 149. ↩

- Ibid, p. 150 ↩

- Ibid., p. 155. ↩

- Ibid, p. 152 ↩

- Asamblea Nacional de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela (2010). Ley Orgánica de las Comunas. Accessed at: http://www4.cne.gob.ve/onpc/web/documentos/Leyes/Ley_Organica_de_las_Comunas.pdf; pg. 1. ↩

- Machado, D and Zibechi, R. (2016). Cambiar el Mundo Desde Arriba. Bolivia: Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Laboral y Agrario; pg. 13-14. ↩