Alex James reviews Rodrigo Nunes’ latest book Neither Vertical nor Horizontal, finding a refreshing new vocabulary for talking about organization that raises difficult questions rather than providing simple answers.

Often, conversations on the left about organization can go around in circles- if they even begin at all. A regular trope of these painful discussions inspires the title of Rodrigo Nunes’ book, Neither Vertical nor Horizontal. As the trope goes, social movements at the turn of the 21st Century loved to stress their ‘horizontal’ nature, in contrast to those horrid ‘vertical’ creatures of the old left. In the aftermath of the anti-globalization and Occupy movements, others on the left began calling for more ‘verticality’. The old horse of ‘we need a revolutionary party’ was dragged out yet again, tired, draped in sect colours, and thoroughly flogged, usually in newspaper form at a demonstration.

For those who have experienced organizing conversations on the left, dyads like verticality/horizontality, leaderless/vanguard, decentralized/centralized, from above/from below, and so on in practice often mean the end of a meaningful conversation. Propositions like ‘we need to be more centralized’ or ‘it’s important socialism comes from below’ function primarily to evoke an emotional response, particularly from those already on-side, or for that matter, in-organization. Online, as we’re being sucked into the attention economy of social media, this tendency can worsen.1 Such organizational statements, rather than providing any guidance or analysis, seek a boo/clap response in the form of likes, providing comforting affirmation of the usual tropes.

This is not a new problem on the left, it is one that goes further back into the 20th Century, though I’m sure historians can provide older examples. The break between Stalin and Trotsky created perhaps the mother of all dyads. Polemics of Stalinist organizations and countries continued throughout the late 1900s, often allowing socialists to avoid analysing the politics of the four General Secretaries in the aftermath of Stalin, changes in Soviet political systems more widely, nevermind the diverse set of Warsaw Pact countries to the USSR’s west. In the worst cases, such language was applied in highly inappropriate contexts, for example reducing the experiences of the Cuban and Chinese revolution and their leading figures into the catchall term of Stalinist. At the same time, Trotskyist, came to be applied to exclude, censure, and remove ‘wreckers’ from a whole host of organizations irrespective of their actual politics. It allowed many to engage in sectarian conflict with other socialist organizations, and secure the ‘immortal science’ from its critics, as well as any intellectual development.

The above is one particularly charged example, but a crucial historic one, where the terms long outlived their namesake organizations, movements, and eponymous figureheads. When discussing organizational issues, terminology, particularly when well-defined and applied in the right context, can initially provide some insight. Over time, and particularly where there exist some group battlelines or nascent identities, terms come to lose analytical rigor. Ultimately, only invoking an emotional cry from the clique, making clear further analysis is not needed.2

Today’s head-butting and sniping around political organization reflects the above process in action. Perhaps horizontal meant something once. Now, it often means nothing. Looking to organizational writings from the 2010s, Nunes assigns them into two broad categories:

Either they call for a search for new forms but are frustratingly reticent when it comes to spelling out what those might be; or they are in fact pleas for a return to some redefined notion of the party, the contours of which tend nonetheless to be left equally vague.3

Neither Vertical nor Horizontal comes at an opportune time for discussions about organization, as it has been an inopportune for the leftover the last few years, at least in the core. For example, conversations about how the British left should organize are urgently needed4 in the wake of Corbyn’s ousting and a mutating Conservative party. Nunes’ book, more than anything, attempts to overcome the dyad/boo-clap conversations we have been having, by demanding a more generative vocabulary.

This article, as far as it can, has two purposes. Firstly, to articulate some, but not all, of the key concepts of Nunes’ work. Following this, it looks to apply its vocabulary to the idea of cadre building and considers some aspects of organization regarding the Labour party.

Steps in Nunes’ Dance

First, Nunes demands we ask – what is organization? Before we can get to the prescriptive questions of what organizations ought to be, make our boo, and clap demands, we must begin with consensus on what it is. In doing so, “the question of organization thus ceases to be an arena for the endless reiteration of fixed positions and becomes instead a shared worksite in which everyone has to deal with the same set of problems, even if coming at them from different angles.”5

In doing this, Nunes makes a further leap, arguing that this reveals the “unspoken assumptions that normally surround it… that there is a single organizational form to which all organizations should conform, or even a single organization that should subsume all others.”6

Instead, bringing in environmental metaphors, Nunes demands we think of political action ecologically. This consists of seeing ‘intentional political organization’, for example organizing a communist party, as one form of organization on a continuum, rather than the be-all and end all of organization. In this sense, for Nunes organization is everywhere. What matters is how its various forms relate to one another within the ecology and to the ecology itself.7

How then do we even begin to analyze the ecology or the relationships between forms of organization? Nunes responds by arguing we must tackle these questions by “resituating the observer in the world regarding which an observation is made, exposing the falsehood of a contemplative stance.”8 Thus, those discussing and engaging in organization are:

Agents with limited information and capacity to act, for whom the future is unknown and open, and who wish to increase the probability of certain outcomes over others without ever having absolutely certain knowledge of what might be the best way to do so.9

Marx, paraphrasing Shakespeare, once spoke of revolution as an ‘old mole’, invoking not just the idea of working methodologically in darkness, but also emerging suddenly.10 In a more negative light, for Lucio Magri “the ‘old mole’ has been burrowing away, but being blind he is not sure where he comes from or where he is going; he may be digging in circles.”11 To turn the metaphor further and onto a more zoologically accurate path, Nunes wants us, as revolutionaries, and therefore as old moles digging in circles, to stop and recognize we have seen only darkness and the dirt in front of us for so long. We should let this humble us, show us how little we know, and then come together to begin seriously asking how we might emerge into the light. There is no god trick, no perfect organization, no shortcuts12, only frank conversations with limited information.

Organization everywhere, spontaneity nowhere

Returning to Nunes’ first crucial issue, switching the order of analysis from what organization ought to be to what it is, – a question emerges. Precisely how does Nunes see organization, or to put it more limitedly, political organization?

For Nunes, political organizing:

Concerns the assembling and channeling of the collective capacity to act in such a way that produces political effects.13

Underlying this conception of organization is Nunes’ interpretation of Spinoza’s concepts potestas and potentia. Potestas consist of power over: the ability of the boss, the landlord, the police to control others. At the same time, potentia consists of capacity to act, as yet unrealized. Thus, the potestas the capitalist class has over the working class, requires workers to come together in forms of political organization mobilizing their potentia in collective action14 to effect political change.

This is a very wide understanding of political organization. But this makes it possible to turn certain problems on their heads. Rather than seeing those on the left outside of a formal communist organization as unorganized, non-alignment can be framed as its own form of organization. Hence, the manners in which the unaffiliated relate to each other, to formal organizations, and to those with potestas over them become issues of investigation. Organizations in the traditional sense come into view in a background of relations between different forms of Nunes’ sense of organization, which expands the descriptive lens outwards.

We have two components here: understanding organization as relating to potestas/potentia or the power agents have to act, and understanding organization as appearing in necessarily plural forms. This leads Nunes to the claim that “successful processes of social change are neither wholly centralized or dispersed, they are always distributed.”15 In other words: organizations of varied forms participate in social change, with centralization and dispersion merely being relational characteristics, not absolute forms.

When individuals come together in a common project it necessarily also implies self-constraint, even if the constraint is just one of ensuring your own energy is put into a project. Herein is the potentially traumatic nature of organization. According to Nunes, organization is a pharmakon, it cures and injures, it might just as much expand the potentia of agents to act, it might also give agents potestas over others. Many have ‘the habit of perceiving organization only as danger and not also as enabling condition’.16 This fails to see that a decision to be outside of formal organizations is itself still a form of organization, and one that likely neglects the issue of expanding potentia in pursuit of change. Talking only of spontaneous action, against organization, simply avoids the question of how spontaneity is organized. Just as Foucault spoke of anti-Hegelianism as “one of his tricks directed against us, at the end of which he stands, motionless, waiting for us”17, Nunes sees an obsession with spontaneity contra organization as a trick, with organization very much still holding us in its grip.

Stay with me. If organization is everywhere, and is necessarily plural and distributed, is Nunes’ account consequently merely an affirmation of eclecticism? Is it a demand for letting a thousand forms of organization bloom? The short answer is no. The longer answer is that:

It is simply to assume, first, that plurality is a given, which means that the question of organization is never about the one organizational form or the one organization… This entails secondly, the belief that plurality does have a value in itself, to the extent that it can be both a source of novelty and a guarantee against the concentration of potestas.18

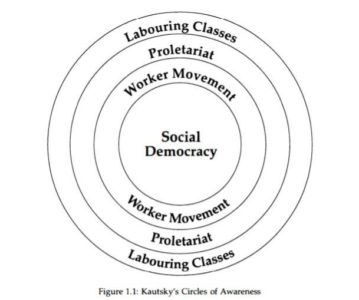

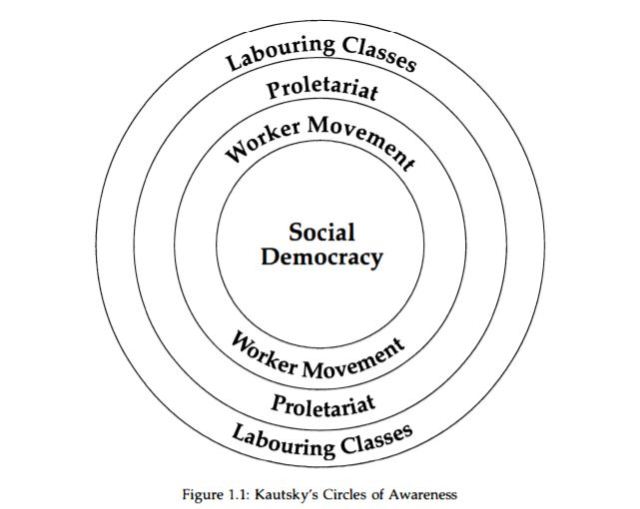

Assuming there are multiple moving parts, organization necessarily becomes a conjunctural question of how things relate to each other. Take for example the merger thesis, of communism (nee social democracy) as the merger of the workers’ movement and socialism19, and in turn Lih’s example of Erfurtianism as a series of concentric circles.20 Using the vocabulary of Nunes, to produce the political effect of removing the potestas the capitalist class has over us, it is necessary to expand the potentia of the varied forms of socialist organization, the potentia of the varied forms of organization in the workers’ movement, and to develop strategic ways in which these forms of organization relate to each other and to their ecology. However, arguing there is a monolithic form this may take, or allowing one form of organization to eradicate plurality (i.e. by subsuming all activity within a party opposed to factions or any form of internal debate) facilitates the possibility of unleashing potestas. A world where self-identifying socialists may oppress workers, socialists may oppress other socialists, and workers may oppress each other.

Cadre building through Nunes’ work

To expand on these ideas, let us look at the particular problem of ‘cadre-building’ – the relation between agents and formal organizations. Alternatively, to reframe this process in Nunes’ own language, the effect that different forms of organization have over time on the potentia of agents – both before, after, and during their time engaged in any given organization.

In his short biography of Lenin, Lih makes the point that What is to be Done and much of Lenin’s early writing resounded with the group of underground organizers within Russian Social Democracy, the praktiki.21 They saw their own experiences, strategic thoughts, and inspiration for further organizational pathways reflected in Lenin’s assessment of events. Contra Lenin as a monolithic party builder, his writings came to mobilize and articulate the viewpoints of a diverse section of the party cadre. Historic episodes like this remind us that the relation between a formal organization and its participants is of central political importance.

Thinking through strategy for a formal organization might demand we consider what kind of agents they produce. What potentia is imbued into the agent because of the particular endeavor they engage in? One might join a socialist organization, wherein you read a lot of Lenin, Trotsky, and Marx and attempt to sell papers. This is most certainly so if you are British. Alternatively, you may be involved in the organization of workplaces, tenants organizations, or the like, alongside your political development as a socialist theorist. If the organization folds, the potentia, the powers an individual has, are entirely different between these cases. In the latter, individuals are still capable of going into new workplaces, new communities, and building something new. In the former, the individual is returned to their pre-org state, if not to a worse one, damaged in their ability to interact with others from burnout and sloganeering.

Cadre building comes to relate to potentia’s variance beyond the organization, in both a negative and a positive sense. Individuals across the history of the left have joined organizations, gained skills, powers, and abilities that they have then gone on to use beyond the organization in strange ways. Murray Bookchin learned to orate and polemicize in the CPUSA, then in American Trotskyism, before his engagements with countercultural circles led him towards anarchism and ultimately social ecology.22 CLR James, in skills gained polemicizing, speaking and writing in the ILP and American Trotskyist movement23, then went on to deploy such skills in his own organizations and in his relationships with subsequent organizers (both with Martin Glaberman, who in turn was crucial to the Detroit League of Revolutionary Black Workers24 and in his relationship with Darcus Howe and others in the Race Today office25). In different situations, individuals have experienced frustration or have been forced to engage in vastly inappropriate tasks within organizations. In the worst cases, many have experienced potestas expressed against them in interpersonal violence or other forms. These individuals experience the trauma of organization and the consequential reduction in their potentia. One could think of the many examples within the British left here, of figures forced to sell papers for years on end only to burn out, unable to really even organize their workplace. Or worse, of the many examples of comrades leaving politics entirely, as a result of interpersonal violence organizations facilitated or covered up.

In sum, there is a politically interesting dimension of Nunes’ new vocabulary – if we accept a plurality of organizations, what does it mean to begin to strategize assuming we shall experience collapse, failure, or the end of a formal organization, but with the wish to still build working class potentia? Does building an organization with a focus on cadre building have a necessarily different appearance than building an organization for other political effects?

Framing the English left through Nunes’ vocabulary

Let’s consider some further aspects of Nunes way of approaching the problematic of organization, particularly by looking towards the English left.26 In the aftermath of Corbyn’s defeat in 2019, the election of Starmer, the collapse in Labour Party membership, and most recently the deselection of Corbyn from the Labour Party, three broad strategies have emerged on the English left – Stay and Fight, the formation of a new left party, and a return to base building.27 To use Nunes’ terminology, this crisis of organization relates to two examples of potestas over workers and the left, that of Johnson’s government and the Labour right – what matters are the forms of organization that can enhance the left’s potentia in response.

The Stay and Fight strategy broadly consists in the assertion that one should retain Labour party membership and participate in organization within the party itself. In short, potentia of organizations of the Labour left, in response to the potestas of the Labour right. A crucial insight from Nunes’ vocabulary is that much of the cruder Stay and Fight narrative relies on the assumption that the Labour Party is the only vehicle capable of defeating Conservative rule. This falls foul of neglecting the necessarily plural nature of organization. Such an analysis ignores even basic aspects of the ways in which organizations around Labour have brought about the political effect of a change in government, not least of all the link between trade unions and the Parliamentary Labour Party.28

More advanced forms of Stay and Fight look to particular forms of organization within Labour to bring about more limited political effects. For example, fighting for a Momentum-led slate on the National Executive Committee of the party, organizing for mandatory reselection to attempt to change the composition of the PLP, or even organizing a slate around the Socialist Campaign Group (SCG). All of this is to recognize that the Labour party is an ecology itself, and to consider what forms of organization can relate to each other to bring about political effects in this space. What these analyses have thus far failed to do is really grapple with the potestas of the Labour right, of the many forms of organization that attempt to exert power over those who threaten their position: the whips’ likely deselection of any SCG MP who crosses a line, the role rightist trade unionists, the PLP and Leader’s office members have in containing NEC disputes, and the many organizational forms that mobilized throughout the Corbyn leadership against changes to selection.

More than ever though, there is a lack of articulation by Stay and Fight advocates of the strategy towards the areas of organization that do not relate directly to national policy, the Front Bench, or the PLP. This is particularly true with regard to councils and other local elected officials, though this may change in the face of the May 2022 elections. For a long period, the ineptitude of Labour-led stronghold councillors, often in the hands of property developers, facilitating austerity logics, or worse, has led to a particular malaise. Individuals who would have previously identified strongly with Labour organizations associate it with anti-worker local government, damaging the organization’s relationship with its historic base.29

Nunes’ framework provides further insight in refusing to see those who have left the Labour Party as unorganized or apolitical, as Stay and Fight advocates often do. It recognizes that those who have left or decided to become inactive are engaged in their own form of organization, though potentially one with reduced potentia in contrast to previous years. The ‘Corbyn generation’, those politicized to social democratic and even communist ideas under his leadership are not going away. One of the major strategic failures of many of the far-left organizations outside of Labour is their inability to recognize this group as a potential cadre, as opposed to the already existing circle of organizers ‘left of Labour’. Similarly, those who advocate ‘Stay and Fight’ may wish to consider how it is possible to still have generative relations with this block of recently politicized actors.

Nunes’ way of understanding organization ultimately disrupts the idea that engagement with the Labour Party is an all-or-nothing affair. For those who are in formal organizations outside of Labour, who recognize its major institutions as broadly capitalist in nature, there may be particular political effects where it is necessary to engage in a different way with Labour. One thinks here of the lone revolutionary in rural England, where a local Constituency Labour Party (CLP) presents a space to build novel alliances and ultimately forms of organization that transcends the limits of the national party. At the same time, it may be the case, if for example you are attempting to organize insecure tenants in Newham, that the institutions of the local Labour Party, which dominates the council yet continues to promote gentrification and anti-worker housing policy, are a dead end. The point would be to approach the question recognizing the uncertainty, but thinking through what potentia there is in the particular ecology you want to intervene in, what forms organization takes and the potential relations that could be made, and deciding a strategy to pursue the political effects one wishes to bring about. Remember poorly sighted moles, we’re forced to gamble with what we’re given.

Alternatively, there are those on the English left who argue for the formation of an entirely new party of the left, most recently kicked into gear by (likely baseless) suggestions that Corbyn plans to set up a new party.30 An immediate response to this would be typically Nunesian, namely that those advocating for a new party are often starting from the ‘ought’, before the ‘is’ – the party as the only form of legitimate organizing, and as such the most ‘mature’ or developed form that has to be developed by the left. They share the same trap in thinking as the Stay and Fight advocates.

A further point would be to recognize that there may be a role for a new party within England, but such an argument should start from a strategic wager that a party has a particular function. Nunes himself in his reflections on the party form31 suggests that the turn towards Corbyn’s Labour may have been based on a particular strategic wager – ‘that it could function as a shortcut in the process of political recomposition’ – a bringing together of certain social forces to form a base.32 Furthermore, Nunes suggests that the party within an ecology ‘performs a function that no other organization does.’33 This reflects similar sentiments which deserve greater engagement from those interested in the party-form, whether discussing the party as ‘articulator’34 or in ecological Leninism.35

Most advocates rarely flesh out their call for the party beyond an alternative election-participating vehicle, which faces the ecological problem of Britain’s anti-democratic electoral system and the problem of building a base. As such, most of these calls reflect thinking that reduces politics, and the practice of organization, as Nunes critiques, to the party as the only ‘true’ form of political organization.

Finally, there are those who argue for a move out of electoral politics entirely, in the form of ‘building the base’ or engaging in forms of community, trade union, and other organizing instead of electoral activity.

The wager of such a strategy is that during and after the Thatcherite offensive, the smashing of unions, the decomposition of the ‘industrial working class’ due to deskilling, outsourcing, and more has left the workers movement with extremely limited potentia. This necessarily requires a new generation to engage in organizing within the ecology to build the potentia of the working class. Without the capacity of the working class to act across several neglected organizational forms, no party can have a base.

A further attraction of this strategy is its attention to cadre-building within an ecology, often due to the frustration many feel having ‘cut their teeth’ in the Labour party. The argument goes that being a Momentum or CLP activist may increase certain capacities to act, but not the ones needed to, say, organize a workplace or tenants union. Thus, building the base often has the dual function in Nunes’ language: ensuring energy is exerted to build potentia within the workers’ movement and making wagers about the kind of skills needed from socialists to support this.

What base building still neglects, as discussed with the creation of a new party, is the particular function that a party might hold within an ecology. Crucial here is a return to Mohandesi’s idea of the party as articulator, which can link together these disparate forms of organization in novel ways. To twist this through Nunes’ language – one argues for the party, or some articulator, on the wager that it provides a function expanding working-class potentia in such a way as to bring a political effect, not because it ‘is organization’ or represents organizational maturity, but rather because it is based on the actual needs perceived and the wager that such a function is needed to bring about an effect.

In looking at these three broad perspectives, it is worth stressing the embeddedness of the agents making these wagers when discussing strategy. There is no contemplative perspective that can look at organizing from the outside and make a certain estimate. In fact, many of the enlightened commentators of the English left who refuse to acknowledge this are acting not as strategists but more likely as “wallet inspectors” – hiding their own biases, interests, or stakes in a project for gain. Commentators might be advocating a strategy for a whole host of reasons – it might be the best wager they have following a Nunesian assessment of existing organizations, it might be a misguided insider strategy due to neglecting some form of organization not perceived, or worse, it might be a grift where their own political significance depends on public activity and consciousness being oriented to a particular organization.

I have attempted to avoid as far as possible polemic for a particular position, and merely attempted to trace some of the problematics when framed in Nunes’ language. However, I should reflect on my own embeddedness, my own limited viewpoints, and wagers. Despite being politicized by Corbynism, I have never joined the Labour Party, in part due to my own disillusionment with how it organizes itself within my childhood region.36 This felt later confirmed by my experiences from housing organizing in East London, where we see Labour’s continued support for policing and conduct against its working-class constituents. At the same time, I agree with Alfie Hancox’s assessment37 that there needs to be some base-building strategy that increases the potentia of the workers’ movement in the aftermath of its multi-decade hollowing. That this is necessary for any mass worker politics to succeed is my wager. At the same time, where I am uncertain is on the very question of the party’s potential function, and how one builds a party that can act as an articulator, a function I believe is necessary, in the anti-democratic ecology of Britain.

Untapped potentia

Let us return to Neither Vertical nor Horizontal and what this brief essay has attempted to explore. Firstly, I have given as far as I can a summary of the basic elements of Nunes’ approach to organization. Nunes sees political organization as everywhere, necessarily plural, containing within it the tensions of potentia and potestas, and finally ultimately related in a complex ecology. To explore these features, Nunes creates a vocabulary to begin conversations about what organization there is, and therefore what organization we may desire, as agents seeking a particular change. Crucially, when we work from the is to the ought, we should recognize that we have limited information and must make a wager. Having done this, I have given a theoretical example of what the idea of cadre-building looks like in Nunes’ vocabulary, and then similarly to debates on the English left.

This leaves much untouched, and I hope this article will merely form the start of engagement with Nunes’ work. Not least of all, chapters 5 and 6 of Neither Vertical nor Horizontal introduce further flesh onto Nunes account of political organization, by articulating the following concepts: organizing cores, vanguard-function, diffuse control, platforms, diversity of strategies, and Nunes’ account of parties. All of these contain within them enough content for anyone concerned with organization to mine, critique, and develop into their own full-length articles.

There remains in my view one final problematic to raise about Neither Vertical nor Horizontal, which is its own density and the difficulties of attempting to construct a new vocabulary of organizing. Ultimately, Nunes pulls from Bogdanov’s Tektology38, systems theory, the philosophy of Simondon, and the many different concepts of and interlocutors with Spinoza. This creates a dense, clumsy, and often difficult to read theory, as is often the nature of attempts to buck entire ways of approaching problems by injecting new frames, concepts, and vocabularies.

Yet there is always a shelf life in this regard, particularly in the attempt to avoid the performative dyads of the past. A crucial problematic of Nunes’ theory therefore relates to the twin concepts of potentia and potestas. One should not have to become an expert in Spinozist philosophy to become a good thinker on organization, though one can wager it could help. What these concepts at a minimum do, which any non-philosopher can comprehend and welcome, is to ask where power is, and what sort of power is it. But pulling at the thread between the two differing conceptions is where Nunes’ yarn can unravel. There is a crude Nunesian vocabulary possible that assigns organizing ‘we ought to like’ with potentia and institutions ‘we don’t’ with potestas, in the hope of pre-empting the ought by fixing the is. If we are to clarify this problematic as organisers, to understand why organizations from the Labour right might be considered potestas, as opposed to potentia, greater care needs to be taken in linking these concepts to a class conception of history, and the role the left gives the working class in this. We shall see if such a crude use of Nunes emerges.

Neither Vertical nor Horizontal should be crucial reading for those attempting to overcome the impasses we face on the left. Even if one is not convinced by many of its concepts and terms, it demands we face organizational questions with a clarity we have lacked. For that, it is to be commended

- On the strategic orientation of the left to online spaces and the problems they cause a challenging account is Richard Seymour, The Twittering Machine (London, The Indigo Press, 2019).

- Trotskyism and Stalinism is one such historical dyad, as is the further debate within Trotskyism between Worker States/State Capitalism. To compare and contrast, review the dispute between Bukharin and Lenin around the category of state capitalism in Stephen Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution, (Oxford, OUP, 1980) p28-43 and its later usage in the International Socialist tradition. In the former, it marks an active concern regarding how socialists are to organize an economy and effect the transition towards communism, in the latter it more often than not acts as a designation, a line, which all subsequent political positions naturally flow from. As Lin Chun articulates, the use of state capitalism in a world without a substantial arguably non-capitalist formation means ‘state capitalism, most commonly applied, can mean anything, as it signals nothing about important differences amongst such states, between various phases of a trajectory of individual cases, or between divergent development possibilities.’ Lin Chun, Revolution and Counterrevolution in China (London, Verso Books, 2021) p310.

- Rodrigo Nunes, Neither Vertical nor Horizontal (London, Verso Books, 2021) p4.

- A welcome contribution in this regard is Alfie Hancox, ‘Escaping the Labour Left ‘Safety Valve’: Towards Dual Power in Britain’, Cosmonaut (February 2021), https://cosmonautmag.com/2021/02/escaping-the-labour-left-safety-valve-towards-dual-power-in-britain/.

- Nunes, p5.

- Ibid.

- Thinking organisation ecologically is not an idea simply devised by Nunes. For a further recent example of this idea, particularly with regard to Lenin and the climate movement, consider Derek Wall, Climate Strike: The Practical Politics of the Climate Crisis, (London, Merlin Press, 2020).

- Nunes, p11.

- Ibid. p. 10-11.

- Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, (1852) VII. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch07.htm

- Lucio Magri, The Tailor of Ulm: A History of Communism (London, Verso Books, 2018) p17.

- Unexplored herein, there is a potentially fruitful dialog between works like Nunes’ and the resurgence of works attempting to ‘skill up’ organisers, such as Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (Oxford, OUP, 2016)

- Nunes, p21

- Nunes makes further analytical distinctions between aggregate and collective actions, and distributed action which is between these two poles. For the purposes of this article, this exploration will not be touched upon. Nor will the certainly contentious issue of what a political effect is.

- Nunes, p34.

- Nunes, p38.

- Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language (New York, Pantheon Books, 1972) p235.

- Nunes, p49.

- Karl Kautsky, The Historic Accomplishment of Karl Marx (Cosmonaut Press, 2020) p29-44.

- Lars Lih, Lenin Rediscovered: What Is to Be Done? in Context (Chicago, Haymarket Press, 2008) p41-110.

- Lars Lih, Lenin: Critical Lives (London, Reaktion Books, 2011) p70-72.

- Janet Biehl, Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin (Oxford, OUP, 2015).

- Eds Scott McLemee & Paul Le Blanc, C.L.R. James and Revolutionary Marxism – Selected Writings of C.L.R. James 1939-1949 (Chicago, Haymarket Books, 2018).

- Dan Georgakas & Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I do Mind Dying – A Study in Urban Revolution (Chicago, Haymarket Books, 2012).

- Leila Hassan, Robin Bunce & Paul Field, ‘Here to Stay, Here to Fight: On the history, and legacy, of ‘Race Today’, Ceasefire (October 2019) https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/stay-fight-celebrating-race-today/

- To talk of a coherent British left is broadly incoherent due to the different conditions across Britain, beyond asking how Welsh, Scottish, English, and elected officials from the North of Ireland relate to each other in bodies like Westminster. As such, this conversation will mainly be focused on the English left and Labour, itself not homogenous, but necessarily recognizing the different ecologies of the components of the so-called ‘United Kingdom’. A good introduction to this area is Tom Nairn, The Break-Up of Britain (London, Verso Books, 2021).

- Such positions are themselves a simplification, but for the purposes of showing Nunes’ way of conceiving organisation in action, as well as indicating fruitful ways to reframe the conversation.

- For a study that takes seriously the different organisations that make up the Labour Party, such as trade union bureaucracy, and the organised bodies of the PLP, it is worth reading Ralph Miliband, Parliamentary Socialism: A Study in the Politics of Labour (London, Merlin Press, 2009).

- For two explorations of this theme, one in London and one in the mythological ‘Red Wall’ see Mike Makin-Waite, On Burnley Road: Class, Race and Politics in a Northern English Town (London, Lawrence & Wishart, 2021) and Duman, Hancox, James, and Minton Eds. Regeneration Songs: Sounds of Investment and Loss from East London (London, Repeater Press, 2018).

- Emily Ferguson, ‘Jeremy Corbyn considers launching new party to rival Keir Starmer if his not reinstated as a Labour MP’, inews (January 2022) https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/jeremy-corbyn-new-political-party-keir-starmer-reinstated-labour-mp-1392176

- Again, it’s not my intention to cover all the features of Nunes’ final account, pages 224-239 cover his assessment of the party form, and likely deserve an entire article of their own.

- Nunes, p237.

- Nunes, p231.

- Salar Mohandesi, ‘Party As Articulator’, Viewpoint Magazine (September, 2020) https://viewpointmag.com/2020/09/04/party-as-articulator/

- Gus Woody, ‘Revolutionary Reflections – Moving towards an ecological Leninism’, rs21 (December 2020), https://www.rs21.org.uk/2020/12/18/revolutionary-reflections-moving-towards-an-ecological-leninism/ and Wall’s aforementioned Climate Strike.

- The so-called ‘red wall’ of North England remains full of particularly inept and often outright hostile Labour politicians and institutions. Though the politically inept descriptions of the region, the conduct of its politicians and the like show the paupacity of English Marxism in this regard.

- Alfie Hancox, ‘Escaping the Labour Left ‘Safety Valve’: Towards Dual Power in Britain’, Cosmonaut (February 2021), https://cosmonautmag.com/2021/02/escaping-the-labour-left-safety-valve-towards-dual-power-in-britain/.

- Whilst one may wish to start with Tektology, perhaps the best area to start in this regard is the summative/popular outline written by Bogdanov – Alexander Bogdanov, The Philosophy of Living Experience (Chicago, Haymarket Books, 2017).