Introduction

It is agreed that to deal with a public health crisis, the African continent requires a new public health order that prioritizes local populations and a health system that is resilient, adaptable, and capable of resisting the possible disease threats in this 21st century. Strengthened continental and national public health institutions, as well as improved local manufacturing of vaccines and diagnostics, are a necessity. Most importantly, the training, and retention of a competent, indigenous public health workforce is critical if any long-term health strategies are to be maintained.

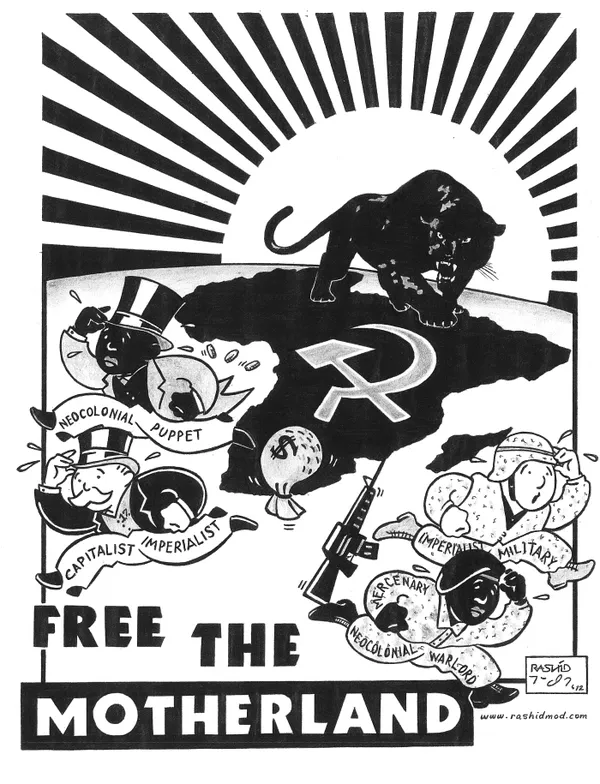

Global South countries have been fighting for the right to manufacture and import affordable generic versions of the Covid vaccines. The USA, UK and European Union joined forces to block them at the WTO. Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Iran are countries that show example for autonomous action as concerns the welfare of their citizens even amid crippling sanctions leveled by the ‘west’ against the populace in essence. African countries on the other hand, stand in an unnecessarily vulnerable position as far as health-based technologies are concerned. Little has been said about the manufacturing hubs that were to resume activities in Egypt and Morocco. As Cairo readies itself for part of its 10 million dose vaccine order, other African countries only make the continent take a weaker negotiating position when purchasing vaccines that are experimental, designed in vastly different contexts, and not readily accepted by their various populations. While China may continue to win the pageant of altruism as far as Africa is concerned, Africa continues to play the role of the perpetual recipient of charity.

The above context is to demonstrate the absurdity of the status-quo vis-à-vis vaccine distribution within Africa and the corporations that are involved. While back in 2020, there was media hysteria as to the “emergency” that is the COVID situation in African countries, much ado was made about the acquisition and distribution of vaccines to vulnerable African populations that foreign, especially Euro-American institutions are so quick to identify. Recently, owing to the spiralling conflict in Europe, the IMF in familiar fashion has switched to a more overtly patronising view, suggesting that progress that has been made in Africa vis-à-vis the ‘ravages’ of global health crisis – will be undone. The IMF’s managing director is also quoted as saying that the institution must position itself to build African economies with a ‘strong immune system’.

Intellectual Property Rules – More obstacle than assistance

Waiving IP rules for COVID19 vaccines in the middle of a health crisis should be common sense, but that is not going to happen for a combination of reasons, such as protecting existing monopolies and the interests of capital. Pfizer and Moderna are among pharmaceutical companies making massive profits from COVID19 vaccine orders and a massive aspect of protecting that gain stems from the monopoly control of related Intellectual Property (IP). On the other hand, Pfizer and Moderna have all sorts of legal protections to guard against COVID19 vaccine related injuries.

If Africa is to be on any sort of an even playing ground, an IP-rules waiver for the development and distribution of context-appropriate health measures is the obvious way to go. But as usual, there are always much more sentimental or subtly patronising think pieces, interviews, seminars etc. on why African countries should not -in essence- adopt any measure that has the slightest indication of self-sufficiency. Ancestor John Magufuli’s Tanzania is a prescient example, the president was one of the only African leaders mentioning the need for African countries to prioritize local and context-appropriate treatments for the health crises, John Magufuli was also the only leader to rightly critique the accuracy, and effectiveness of the COVID19 test-kits. The latter case was quietly drowned in a media storm of ridicule-style articles, completely bypassing the reality that test-swabs produced unreliable results after being used on fruits and farm animals.

The existing Intellectual Property frameworks are unacknowledged neocolonial trade laws that divvy up African intellectual resources from countries that fall within English and French spheres of colonial influence, and for clarity they are the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) and the Organization Africaine de la Propriete Intellectuelle (OAPI). The two frameworks are conveniently used within French and English-Speaking Africa and by extension, research and development is heavily influenced by these frameworks. African sourced Research and Development (R&D) is hardly ever funded unless it is produced under the purview of ‘prestigious’ western universities.

While the combined membership of ARIPO and OAPI stands at 36 out of a total of 54 African countries, the remaining 18 non-members opt to rely in their own national IP legislation, and while there is no extensive fault in this expression of independence, African countries still appear as a divided front in vital negotiations. The current health crisis is prime evidence. Within this context, it seems strange that the Pan-African Intellectual Property System is stuck on building a merger between diametrically opposed IP frameworks in the name of ‘harmonization’, as opposed to structuring a ground-up policy that prioritises the needs of African intellectual production as well as research and development.

Disregarding a skeptical view of the status-quo is intellectually disingenuous and naïve. The decision against liberalising vaccine-related IP rules is political, the main beneficiaries of such far reaching decisions are the major pharmaceutical companies who are non-surprisingly the group of entities that have benefitted the most from this seemingly unending health crisis (read below). Governments are regularly influenced by the powerful lobbies that function as public relations arms of major corporations. Capitalistic motives of profit and more market share are the prime objectives regardless of the situation be it a global health crisis or a crippling recession. The important thing is that such a need would not arise in a world where there is a reasonable and equitable distribution of R&D capacity and funding for research.

As in many other patronizing and infantilizing interactions between African countries and Euro-American countries, be it in the defense sector, manufacturing sector, or even the agricultural sector, it is usually implied that the more experienced Euro-American professionals will have to come down and help the lowly Africans with their unending issues which now includes being unable to safely research ways to keep their populations safe from a novel virus even when the continent has the lowest COVID-19 mortality rates by any metric (not that death rates are anything to gloat about) and Africans are included in the research labs where cutting edge work is being carried out in every conceivable industry. Still, the media plays a cynical role of building tension as concerns ‘dangerous’ mutations if the vaccine becomes rampant (re: easily accessible) in poor countries. This argument strikes a superficial economic cord and then subverts a whole discussion about self-reliance in yet another sphere of life and activity, the health sector. The fact of the matter remains that waiving IP rules disrupts the profit bottom-line of many powerful corporations and that is a cardinal sin when operating in a capitalist world economy such as we do.

Political Will, to What End

Following the appointment of prominent Nigerian Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala as the director-general of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the US Chamber of Commerce warned the WTO's director-general not to 'distract' herself with proposals to suspend intellectual property rules in order to distribute COVID-19 vaccines around the world. Similar to the steps that were taken against Femi Adesina of the African Development Bank (AfDB) right when he had a re-election, he was accused by the US of ‘violating ethics of management’ as well as impropriety. The point being that as Dr. Okonjo-Iweala is also a U.S. citizen, representatives of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce still finds it necessary to release disciplinary statements at best or veiled threats at worst.

Malaria has always affected the poor countries that are located primarily along the equator. The tropical weather plays a role and the poor sanitation in impoverished communities also encourages breeding grounds for mosquitoes. As such, the market is not incentivized to prioritize and invest in research for malaria vaccines because most of the affected countries will struggle to finance an immunization program like we are seeing with COVID19 which does not require coverage of 100 percent of the population unlike malaria that would require everyone at risk be vaccinated.

WHO and other global health governing bodies are not under any real political pressure to facilitate vaccine development because poor countries are often diplomatically weak, and productivity loss caused by malaria bears no significant impact on the global economy. Furthermore, the COVAX program is not out of benevolence, but is a donor-led initiative, built around the recognition that if developing countries cannot achieve a level of immunity against COVID19, developed countries will not be ‘free’ because it takes one European business traveller to Africa to contract COVID19 and spread it, cities will be going back into lockdown, just as Nigeria’s first case was an Italian working for LaFarge who made his way to Ondo State. Majority ‘white’ countries are richer, and so capitalism/the free market responds to their pain faster because there is profit at stake. Case in point, the majority of these vaccines, experimental and otherwise, have been bought and paid for by western countries. Capitalism must be identified as the crux of the issue, the insatiable reach for profit at literally any cost as well as the inflicted class-based hardships (millions cannot afford the vaccine programs) in so-called developed countries means Africa is not the only continent at the receiving end of policies that are based on a lack of political will. With this context, a healthy dose of speculation will expect that there will be a malaria equivalent of COVAX.

The Deficits, finance, infrastructure and otherwise

Infrastructure is crucial to Africa’s IP, service delivery, and sustained development. As an infrastructure deficit obstructs development throughout Africa, one observes that control over IP is also connected to social development. When a nation or region has control over their IP, there is the freedom to implement locally sourced and contextually accurate solutions to economic challenges. This is opposed to receiving one-size-fits-all suggestions or frameworks. An example is when countries must adopt prescribed economic policies as condition to receiving financial assistance.

Studies have shown that in Nigeria, infrequent electricity supply hinders development potential of manufacturing Small and Medium, Enterprises (SMEs). Suggested strategies deployed by manufacturing SMEs have included developing the electricity supply, and cost and time reduction strategies. While the power deficit disrupts productivity in the SME manufacturing sector, local SMEs seek innovative and low-cost strategies to overcome institutional and macro-economic problems.South Africa is a proper context that demonstrates the connection between IP and development. Foreign development finance institutions (DFIs) like the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the European Investment Bank act to their mandates of funding specific development projects, and studies showed that the SA government prioritized securing external assistance to fund its infrastructure program. This was because domestic funds cannot be used to cover the infrastructure financing gap.

From renewable energy to infrastructure funding or private sector insurance, the implementation of the concerned policies will be under the purview of the foreign entity, for instance, KFC in Kenya had to import potatoes as opposed to buying from local farmers because “all suppliers have to go through the global quality assurance approval process”.

The impact of IP rights and privileges has produced tensions and reactions that have put development aspirations under that threat. IP has had a serious effect in development, because one can observe that global policy focuses on development and this is related to access to knowledge, information technology, education, medicines, and overall improved welfare.

It has been observed that in Africa, IP rights like copyright have proven inadequate when looking at preservation of intangible culture and heritage. At the same time scholars have expressed the importance of technology in the documentation and preservation of heritage. This is another context illustrating the connection between IP and development. Additionally, it is important to note that IP and technology intersect in the areas of education, agriculture, and tax.

Conclusions

Decolonizing global health will necessarily require the equitable funding of health-related scientific research in the global South, since there is a huge disparity in production capacity, distribution networks, or technical infrastructure. While there is a case for interest in research, the funding is a chronic obstacle to African contribution to the global body of knowledge. Africans have authored just 3% of COVID-19 research papers, despite the fact that 17% of the world's population lives in Africa, reveal two analyses, published in the online journal BMJ Global Health. The journal Cell, stated that roughly 1% of the vaccines used within Africa are produced by African countries and according to Prof. William Ampofo, the chairperson of the African Vaccine Manufacturing Initiative, “a few weeks after launching vaccinations, some countries are nearly exhausting their initial supplies”. Furthermore, there are fewer than 10 African manufacturers with vaccine production and they are based in 5 countries which are Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa, and Tunisia. The noteworthy information is that Africa has roughly 80 sterile injectables facilities which has the potential for vaccine production seeing that primary mode of dosage administration is through vials.

The major impediment to vaccine self-sufficiency in Africa is how the markets are structured. With most African countries being supplied through UNICEF programs, and GAVI and the Gates Foundation vaccination programs, fewer than 10 countries are self-sufficient in terms of procuring vaccines. With foreign patrons being the main sources of vaccines, countries of the continent will be far more vulnerable to so-called market forces, less so if commitments were made to support and patronize local vaccine manufacturing.

Looking past the push for Intellectual Property waivers, material conditions in many African contexts will mean that skill gaps, inadequate investment, and dynamic regulatory environments will not encourage pharmaceutical giants to engage with enthusiasm. Additionally, the long-term demand for COVID vaccines are also a factor in production decisions, suggesting that mass healthcare in this context is not the priority, only capitalist motivations. The mindset is that, there essentially is no need to ramp up support for local manufacturing capabilities if long term demand for the vaccine cannot be determined.

On the acceptance of the vaccines, vaccine products from AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson drew bad press because recipients allegedly suffered blood clots afterwards. This has not helped the scepticism Africans have towards vaccination programs and, the prevalence of media means more people are able to educate themselves even on a rudimentary level about the matters around their health. Admittedly, African markets are not the priority for the manufacturing programs in place and conversely, the average African is more concerned about the quality of vaccines that could be introduced into their communities, than finding out specifics about manufacturing programs their government may or may not implement. The same could not be said about those in positions of governance, who seem more concerned about raising vaccination administration rates as opposed to structurally improving healthcare systems continent-wide.

Finally, although Africans contribute a great amount to the academic work that serves the health sector at large, the continent’s underrepresentation is an indicator that the need for intellectual autonomy is reaching a tipping point and unwavering methods will have to be initiated to tackle such challenges, that the African worker ultimately must deal with.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.