Drawing on the work of moral and political philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, ΔΜ sketches an outline for a possible marxist theory of ethics.

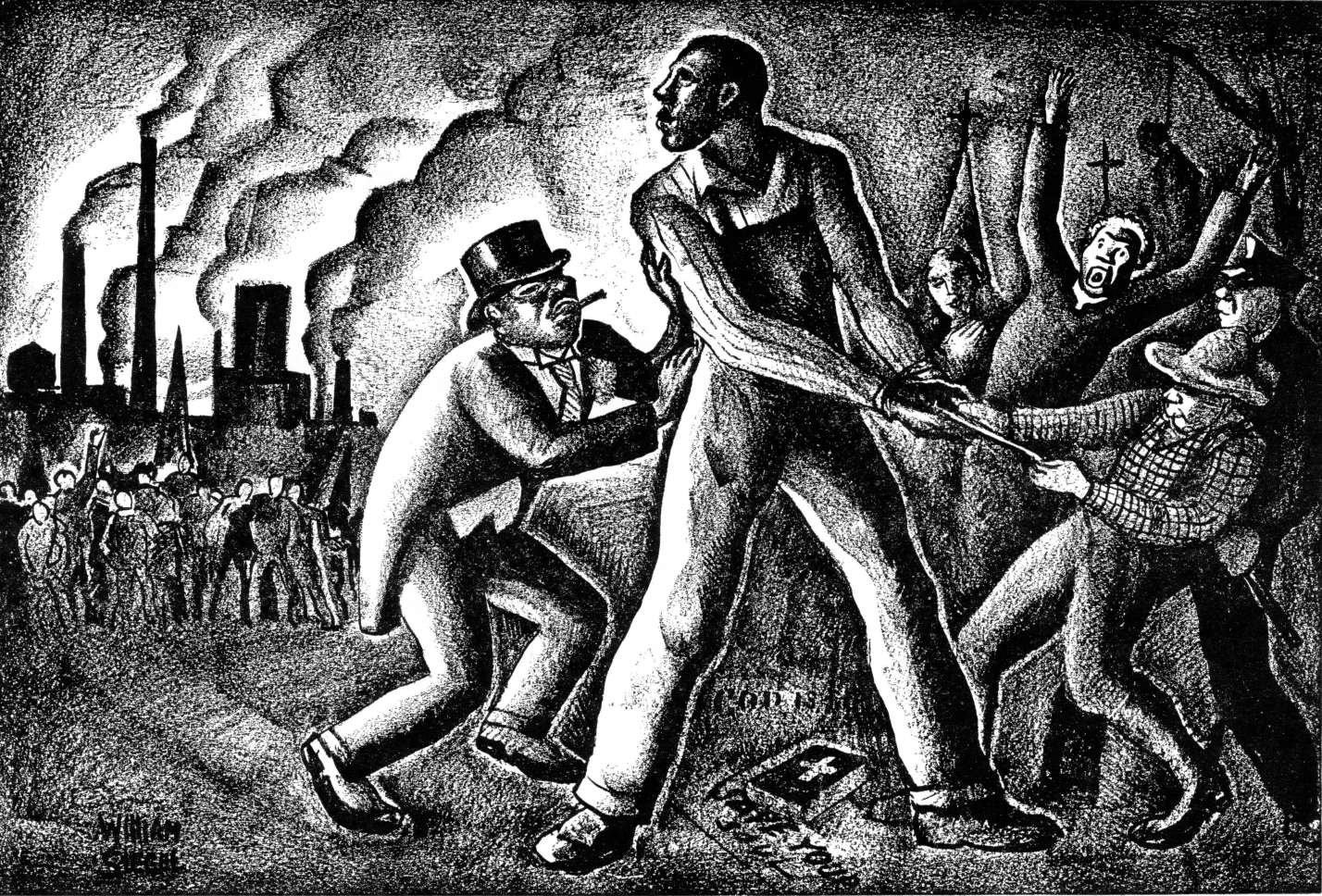

‘He wants more than pie in the sky’ by William Siegel

The dominant position in marxist circles and, consequently, within the communist political movement is that marxism is incompatible with a moral criticism of capitalism. That position is, of course, not without merit and it is even backed by Marx and Engels’ comments on morality. However, and here lies an obvious contradiction, the political discourse generated from communist parties and groupings (independent of how they refer to themselves) often contain moral denunciations of the outcomes of capitalism for workers and other strata of the population. There is much talk about capitalism’s unfairness, the theft that workers must withstand from capitalists, and the inherently unjust outcomes that capitalism generates in all aspects of social life, even outside of the economy. This contradiction between what the theory espouses and what political agents and groups use in their propaganda has not received the necessary attention outside the scholarly marxist community. And even inside the scholarly marxist community, the most pronounced effort to solve this problem is to equip marxism with a notion of distributive justice. However, one obvious drawback of this approach is that it can easily lead to reformist politics or, even worse, the subsumption of the far wider marxist claims and political goals into run-of-the-mill social liberalism. Of course, the process of conceptual clarification needed to solve, or at least move toward a solution to, any issue pertaining to marxist theory requires far more work than one non-academic article. With this limitation in mind, I will attempt to make the case that contra Marx and Engels’ statements, it is possible to criticize capitalism in a moral way and that this moral criticism will not be a hindrance but an extra tool in marxist theory and its political project of human liberation. This will be achieved by arguing that capitalism can be portrayed as unjust, when justice is understood in a particular way. But to preempt one particular objection, we state here that this theoretical proposal will not necessarily vindicate the moral denunciations of the political groups.

To make our point we have to understand what the role of justice, law, and morality is in the classical formulation of historical materialism. We will ignore the relationship between the productive forces and the relations of production and only focus on the relationship between base and superstructure. The base of any society consists of the totality of the relations of production that are present in that society. So technology, the tools of production, and the ideology of any, or all, of its members do not belong to the base. Law falls within the elements that are not part of the base as, contrary to common misunderstandings, the formal part of private property, i.e. the law, is not part of the relations of production. The part of the institution of private property that is part of the base is only the fact that some people have effective control over some forces of production, even before that is legalized. To give a crude example: imagine a secluded community of farmers. Land is considered common property and everyone participates in the communal production process. Now, let’s say that I, along with some other members of the community, form an armed militia and we take over this community, declare the land to be my private property, and everyone else has no choice but to work for me. Now all the farmland is my private property as I effectively control it, even though there’s nothing legal about my claim to this land. Even if, at some point in the future, my claim is legalized in some way, it is a fact that what constitutes the relations of production of this community is not any kind of law that defines what is and what is not legal, but only the fact that effectively I am the owner of this plot of land. So, as we can see through this conceptual analysis, law is not part of the base, i.e. the totality of the relations of production, in the marxist historical materialist theory. To insert law in the base would be equivalent to making the concepts of the theory muddled to the point of nonsense.

The superstructure on the other hand is defined to be the set of the non-economic institutions whose character can be explained by the nature of the economic structure, i.e. the base. The most prominent examples of such institutions are the law, the state, etc. It is important to note that ideology and various forms of social consciousness, like morality, seem to have the same properties as these non-economic institutions according to marxist theory even though it does not fall under our definition. This definition is not uncontroversial. However, given the fact that to justify this particular definition would take us a separate article, we opt to leave it up to the readers to consult the preface of the “Critique of the Political Economy” in order to confirm that this definition is the marxist one. We do, however, have to clarify in what sense is the superstructure “explained” by the base. This explanation is a functional one, of the form “The function of x is to φ.” An example of such an explanation is that “Birds have hollow bones because hollow bones facilitate flight.” In this case, the fact that birds have hollow bones is explained by the function that they serve in the survival and flourishing of birds. In general, this kind of functional explanation is best illustrated by biology and the theory of evolution in particular. But they can also help us explain social phenomena. One example would be that “This rain dance is performed because it sustains social cohesion.” Here, the social phenomenon of rain dances, that is observed in more primitive societies, is explained by the function that they serve in the cohesion of the society. The explanation of the superstructure in terms of the base is similar. In particular, historical materialism claims that, “the superstructure has the character it does because, in virtue of that character, it confers stability on the production relations, i.e. on the base.”1 Now, this claim, while clear, has proven to be contentious. However, given that the topic of our essay is not historical materialism, we will not elaborate on this. We will simply remind that the forms of social consciousness, including morality, seem to play this same functional role with regards to the relations of production. This is an important point that will help us understand the classical marxist treatment of morality.

So, we will now briefly illustrate Marx and Engels’ treatment of morality and the notion of justice (as broader than the laws). Their treatment is purely functional as we will see. For example, as Marx elaborated in Capital Vol. I, the workers sell to the capitalist their labour-power and this exchange cannot, in the long term, be unequal in terms of value exchanged. That means that even if some conditions make it possible for a worker to sell his labour power higher, or lower, compared to its value, then the market itself will create forces that will eliminate this discrepancy. The same holds for any kind of commodity exchange. So in expectation there is no unequal, hence unjust according to capitalism’s own understanding of justice, exchange between owners of any two commodities. But why is this kind of exchange taken to be just in capitalism’s own understanding? Because a notion of justice in terms of exchange of equivalents serves the function of giving stability to the market exchange, of legitimizing (in the ideological sense, not the legal one) the day to day working of this social system. Furthermore, that the capitalist, having bought the worker’s labour-power, consumes the “use-value” of this commodity, the hours of work that can be “extracted,” is well within his right. This may well be exploitation but this particular kind of exploitation, according to Marx at least, is necessary for the proper function of a capitalist society, and given the functional role of justice and law, thus it can only be considered as just. To use Marx’s words: “The justice of transactions which go on between agents of production rests on the fact that these transactions arise as natural consequences from the relations of production. The juristic forms in which these economic transactions appear as voluntary actions of the participants, as expressions of their common will and [..] cannot […] determine this content. They merely express it. This content is just whenever it corresponds to the mode of production, is adequate to it. It is unjust whenever it contradicts that mode.”2 Allen Wood, in many of his articles, as well as in his seminal Karl Marx, is one marxist scholar who shares this view. He claims, similarly to Marx, that “An action, transaction or system of distribution is just whenever it is functional in relation to that mode of production, unjust whenever it is dysfunctional.”3 Hence there exists a marxist tradition, including Marx himself, that understands morality (as claiming that something is just or unjust is inescapably a moral claim) as tied to whatever social system it is embedded in. A different social system, with a different set of relations of production, will have a different moral system.

We now have in place the classical marxist theory of justice and morality. But a question inevitably arises. If a moral system, and a notion of justice, corresponds to a social system in a way that the notion of justice serves the stability of the dominant relations of production then any social system, including communism, must have a corresponding morality and notion of justice. Additionally, if communism is preferable to capitalism for the working class, or even for humanity in general, why is it impossible to compare two different moral systems? Shouldn’t we be able to conclude that capitalism’s notion of justice is, in some objective manner, inferior compared to the communist notion of justice? If this was the case, then it is perfectly reasonable to conclude that capitalism is faced with particular moral failings and hence it is morally preferable to advocate for communism. In line with Marx and Wood’s understanding we can envision two kinds of answers to this question. One possible answer is that this comparison is inherently incommensurable. Both moral systems, one functional to capitalist relations of production and one to communist ones, can only be understood within their own system. To take them out of context in order to compare them would make them not only incoherent, given that they can only be explained in reference to their function, but would also deprive us of a way to judge in a factual and rational way the moral utterances of these two systems. This answer we claim is thus based, at least in some sense, on an emotivist moral theory. Emotivism in moral theory means that moral judgements are, or end up at, expressions of one’s subjective feelings. So within an emotivist understanding of morality the sentence “This is just” simply means “I approve of this” and nothing more. In the emotivist understanding, ultimately this is where the rational justification of any kind of moral claim has to end up. Hence, as emotivists claim, morality is not something that can be rationally settled. This property of emotivist moral utterances is the one that gives credence to claim that the marxist theory of morality is emotivist, at least in some sense.. Since moral systems can only be explained in terms of their function within a given and corresponding social system, it is impossible to rationally settle between two sets of moral claims. Once we remove them from their related social system there is no particular meaning, or reason, to hold or reject any of them. Rationality cannot settle such moral utterances. Under this understanding therefore, we believe we are justified in claiming that the classical marxist theory is some peculiar form of emotivism. It is not of course a traditional emotivist theory since it is, indeed, able to rationally settle the truth of a moral utterance by investigating its functional role, or the lack thereof, within a particular social system. But faced with the necessity of comparing a moral uttering that is functional with regards to capitalism and a moral uttering that is functional with regards to communism, it must shrug its shoulders and admit the failure of a rational approach.

The second kind of answer that can be inferred from the line of thought developed above is that this kind of comparison, even if it was meaningful, would be actively harmful to the political goals of any movement for the liberation of the working class. The reason for this is that since the only coherent moral theory within a set of relations of production is the one that serves a functional role for those relations, then that makes any moral theory inherently conservative. Any moral claim outside of this framework would be discredited in a rational sense as capitalist production constantly relativizes the normative ways that agents should follow if they wish to fulfill their interests. If, for example, a trade union asks for justice and the implementation of particular labour laws (as it should of course) then this trade union accepts the justice of the capitalist system. To abandon this conception of justice and make the moral claim that “capitalism is unjust” would be a logical contradiction. It would also provide the capitalists with a powerful weapon in the “capitalism or socialism” debate, allowing them to portray themselves as the protectors of justice and the people who claim that “capitalism is unjust” as some bad faith agents that reject the notion of justice. Given the negative connotation of being “an enemy of justice,” this would be an unfavorable position for any political movement.

Let us briefly summarize these two arguments. First, a theory of morality, or any notion of justice, cannot be used to make rational claims against the current economic structure. Second, an argument that is in some way derivative of the first and stands alongside this peculiar marxist “mode of production”-emotivist moral theory. If there existed a moral theory, compatible with the overall marxist theoretical and political project, that could be used to make moral utterances that could be judged rationally, then the second argument against a moral condemnation of capitalism (in particular, that it would be counterproductive) would lose its force. It would neither lead to contradictory claims about what is and is not just, nor would it make the people who make these moral utterances appear as “enemies of justice.” Thus, we feel justified enough (not fully however) to try to answer only to the first argument. Our argument will be based on the kind of moral theory that Alasdair MacIntyre espouses and that falls within a broader Aristotelian moral theory. If we can make a coherent argument that is compatible with the marxist theory, and if we can incorporate claims made by historical materialism within our argument, then our objection would prove to be a serious problem for this first kind of marxist answer as the Aristotelian moral theory claims that it can rationally adjudicate between different moral claims and can decide on which ones are correct and which ones are wrong not only independently of any personal preferences of the person who makes the moral uttering but, as we shall see, it is also capable of incorporating claims about alternative social structures.

We shall limit ourselves in outlining only the three components of such a moral theory and why the moral utterances of this theory can be rationally judged as we would like this essay to serve as an illustration that an alternative to the current marxist understanding of moral theory is possible. So, we think that a more comprehensive development of the components of this theory can wait.

The first component of MacIntyre’s moral theory is of course the current state of a person, the person as is and acts in the actual world, as flawed they may be. We can see that day-to-day actions within a capitalist society, and the incentives that are enforced on agents acting within a capitalist society lead to an understanding of justice, as an example of a moral notion, that is in line with the functional explanation we developed above. The second component of this theory is the state of a person as they can be, not only a better version of themselves but as they should be if they are to realize their full potential. As MacIntyre puts it, it’s the “man-as-he-could-be-if-he-realised-his-telos [end].”4 This component, according to MacIntyre, is based on a rational argument about humanity and thus is not equivalent to a claim of the form “what I would like humanity to be.” And why is that? Here, I think, historical materialism can be of help. And this help will come from the marxist understanding of labour and its role as the essence of society, a thesis that V.A. Vazjulin developed in his seminal work “The Logic of History.”

Labour is a necessity for the survival and development of any human society. Without labour a society cannot function but, furthermore, it is through labour that the production process can develop and, subsequently, through this development that a society can fulfill more of its needs, whether biological or social. However, as long as this labour is done as an external necessity, as a means to an end (the end being goods, wages, etc.), then the person that is performing that kind of labour cannot enjoy the internal goods associated with this kind of labour, at least not its full form. An example would be scientific research in medicine. A researcher engaged in such work will probably feel to some degree fulfilled that the outcome of their labour can improve or even save human lives. Unfortunately for them, the external necessities of obtaining funding, creating profit for his company etc. will force them to stray away to what would be the most fulfilling with regards to their goal of improving or saving human lives. And these external necessities cannot be overcome as long as the relations of production are based on private property and on the constant drive for more profit, i.e., as long as the capitalist relations of production are dominant. Thus, for the realization of the “man-as-he-could-be-if-he-realised-his-telos [end],” the establishment of a society where the private ownership of the means of production is no longer present, the establishment of a communist society, is a necessity.

A question will arise that justice is nowhere mentioned in our argument. So we have not yet fulfilled the prerequisites of making a rational moral claim that “capitalism is unjust.” This will be amended now, with the elaboration of the third component of the classical Aristotelian moral theory. This component is, of course, the virtues. The role of virtues [αρετές] in this moral schema is that they have to be part of human personality and must drive human choices if he is to achieve his “telos.” Without them the person will not have a guide in this journey from their current state to their potential state. And it is here that justice appears as a virtue. Justice, according to MacIntyre, is a disposition to give to each person what that person deserves and to treat no one in a way incompatible with their deserts. Thus, the rules of justice are those rules that can secure the proper outcomes for actions that are deemed to be either just or unjust. The virtue of justice is the disposition to obey these rules. And here our argument completes itself. Capitalism is unjust because it creates structural constraints to human action that disincentivize agents from adopting the virtue of justice and instead pushes them to adopt the “mode of production”-emotivist notion of justice and morality. But straying away from the virtues means that, as the virtues are necessary for the realization of the “man-as-he-could-be,” agents within capitalism cannot become “as-they-could-be-if-they-realised-their-telos.” Capitalism cannot push people to pursue the kind of life that is best for them due to its own structural constraints, as we already stated. As a result, capitalism must be accused as an unjust social system and a moral criticism of this system would be both based on a rational argument, one that is free from personal preference, and would not only be compatible with the broader goals of a socialist political movement but such a moral criticism would enhance this socialist political movement, both as a criticism of capitalism and as way of making clear to working people that they can only fulfill their full potential under communism.

In this essay we tried to outline a kind of marxist moral theory, and a subsequent moral criticism of capitalism. For this, we began with Marx’s own understanding of moral theory and we briefly discussed his claims about morality of just and unjust actions within capitalism. Contra Marx, we tried to establish that a moral criticism of capitalism is compatible with marxist goals of rationality and liberation. We will reiterate that we have no illusion that the arguments presented here can prove in a definite way that such a criticism of capitalism is desirable, or even possible. I do hope however that I have outlined a kind of moral theory that can, with further elaborations, fulfill this goal.

- Cohen, G.A. “Karl Marx’s theory of history.” Princeton University Press, 2020. pp. 249

- Marx, Karl. Capital: volume III. Vol. 3. Penguin UK, 1992. pp. 460-461

- Wood, Allan. Marx against Morality in Singer, Peter, ed. A companion to ethics. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. pp. 517

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. After virtue. A&C Black, 2013. pp. 52-53