Harry Zehner urges the left to challenge the ideology of homeownership.

“We want a nation of homeowners, not proletarians.”

A few years ago, I stumbled across this quote — attributed to Fransisco Franco’s housing minister, José Luis De Arrese — in Raquel Rolnik’s fantastic book, Urban Warfare. It’s important for two reasons: first, it demonstrates the very basic class-cleavaging role of homeownership. Secondly, it tells us that homeownership can be intentionally wielded by capitalists to specifically target and defeat class consciousness.

Homeownership is commonly understood through its economic functions. Capitalist economists think of homeownership as a significant driver of growth, debt-fueled consumer spending, and the basis of an asset-based social security system. Critiques of homeownership from the left are also generally grounded in economics, as Marxists highlight the dangerously speculative nature of homeownership, its integration of the working class into circuits of capital, and, as Maya Gonzalez writes, its role as a “material force representing and entrenching the divisions and inequalities within the working class.”

However, there is less debate regarding homeownership’s function on the ideological terrain. It is my belief that identifying and incorporating an analysis of the ideological role of homeownership into our organizing is crucial to building a successful communist tenant movement.

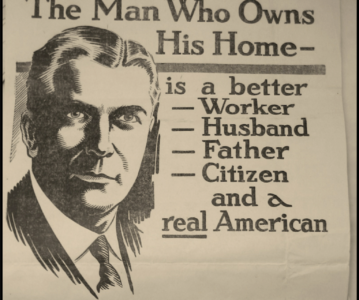

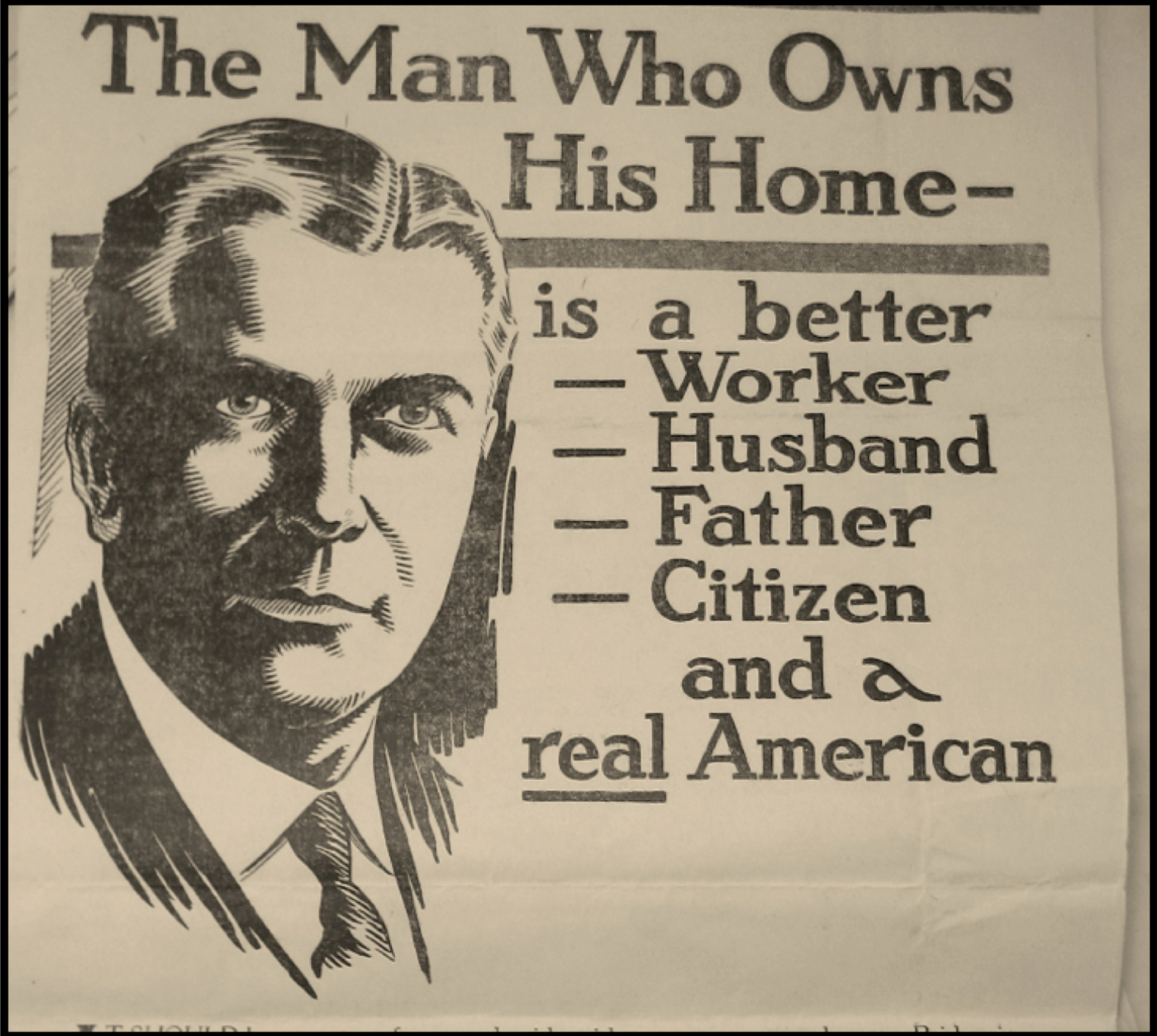

The modern history of homeownership in the US can be traced back to the late 1910s, within the context of an insurgent radical labor movement and the communist threat represented by the Bolshevik Revolution. In the 1910s and 1920s, local, state, and federal officials collaborated with civil society organizations to promote private homeownership as the bedrock of US capitalism. The prominent US senator William Calder argued nakedly: “Every assistance should be extended to enable our people to build or buy homes. Where there is a community of homeowners, no Bolshevists or anarchists can be found.” Herbert Hoover, then the Secretary of Commerce, commanded the massive “Better Homes in America” campaign, proclaimed: “There can be no fear for a democracy or self-government or for liberty or freedom from homeowners no matter how humble they may be,” proselytizing about “the primal instinct in us all for homeownership” as the foundation of a stable, patriarchal, capitalist society.

This period can only be understood as a direct response to the threat of communism — and the accompanying threats to patriarchy and private property relations — presented by domestic radicals and the newly founded Soviet Union. It was defined by blatant US government propaganda like the Better Homes in America and the Own Your Own Home campaigns.

Since Hoover’s heyday, the messaging may have gotten more subtle and implicit (ideology tends to do that, as the initial subjects of ideology become reproducers of that ideology). However, the result — mass homeownership as the unimpeachable, bipartisan goal of US housing policy — has been identical.

Across the political spectrum, homeownership remains essentially unchallenged. It’s understood as superior to renting, as a way to realize your full personhood and US citizenship. It is intimately connected to chasing the American Dream of upward social mobility. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes, homeownership is “reflexively advised as a way to emerge from poverty, develop assets, and build wealth more generally.” The idea of a housing system not structured around homeownership is completely beyond the horizons of US housing policy and discourse.

The US’s fanatical devotion to private homeownership is not a natural outcome, nor is it a politically neutral one. The US government and civil society have intentionally built this prevailing common sense understanding of homeownership through decades of propaganda and hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer-funded subsidies for homebuyers. This understanding argues that: the act of building individual wealth through home equity is a tool of social mobility; that ontological security can be found in the privately-owned home; that the gendered labor of social reproduction should be confined to the private home; and that citizenship resides in property ownership.

This understanding of homeownership does more than produce profits for the homebuilding industry. It is an important component of the US capitalist ideology that keeps the oppressed classes invested in the system and resistant to anti-capitalist critiques of that system.

If we are to take seriously the task of activating a revolutionary consciousness in the US, we must uncover the ways in which the development of that consciousness is stunted and subsumed within the ideology of the ruling classes. Then, we must work to build an alternative common sense understanding of US capitalism, while honestly and dynamically evaluating the ideological basis of our politics. We need to heed the lessons of a century of cultural theorists like Antonio Gramsci, Stuart Hall and Mark Fisher, who have argued that capitalism is maintained not just by force, but by consent. Churches, schools, the family, and other institutions all disseminate the ideology of the ruling classes until it becomes common sense and the exploited masses come to believe that the social order created by capitalism is not only inevitable and unchallengeable but correct and just.

As Hall always reminded us, we must purposefully engage with “the struggle to command the common sense of the age in order to educate and transform it, to make common sense, the ordinary everyday thoughts of the majority of the population, move in a socialist rather than a reactionary direction.” It is an understanding of this task that leads me to argue that the left must explicitly reject the ideology of homeownership in our work. It is essential for the left housing movement in the US to begin to think of the landscape it occupies as the terrain of ideology, and to build a counter-hegemonic housing movement, which explicitly constructs alternatives to the ideology of homeownership. We need to form a systemic critique of private homeownership that doesn’t stop at a discussion of uneven access to homeownership but attempts to smash the ideology entirely. As Mark Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism, our “emancipatory politics” must necessarily “destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order,’ must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency, just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable.”

All of which begs the question: how specifically does homeownership operate ideologically?

Instilling Capitalist Values

Fundamentally, homeownership (and the promise of homeownership) helps instill a belief that wealth is privately created and therefore should be privately controlled. When we accept the framing that homeownership is a primary means of economic mobility and wealth creation, we foreclose the horizons of socialism and obscure the reality that the capitalist distribution of wealth, property, and resources is structurally violent and unequal.

Common sense understandings do not emerge out of thin air. They are intentionally constructed to benefit certain people and classes. Every presidential administration in the 20th century utilized public policy and propaganda tools to promote mass private homeownership as the path to social mobility. Throughout the neoliberal administrations of Reagan, Bush (twice), Clinton, Obama, Trump and now Biden, the promise of mass homeownership has been used to justify cuts to the welfare state in favor of an “asset-based welfare” system, wherein the growth of your home’s value replaces traditional forms of social welfare provision. As Gonzalez writes, “It became crucial to those with homes to protect their property, and to preserve or increase its value by all means possible. Homeowners thus had higher stakes in the perpetuation of the capitalist class relation … ” The pursuit and the material realization of homeownership for millions helps to cement the common sense understanding of oneself as an individual consumer and speculator in a market-based world, rather than a member of a collective capable of organizing for democratic, social ownership of wealth and property.

Therefore, the ideology of homeownership, as both the ultimate form of privatized housing and the bedrock of the American Dream, has been essential to creating a mass common sense understanding that unabashed submission to the free market is the optimal (as well as natural, scientific, and post-ideological) method of structuring social and economic relations.

There are serious consequences to a societal belief that wealth is an individual creation that is earned (or not earned) through hard work, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship. A basic building block of Marxian economics — which has played a consequential role in essentially every insurgent left-wing movement — is the understanding that wealth is collectively created by the working classes, and therefore should be collectively controlled by the working classes. Capitalism is organized around private control of wealth, production, and the surplus value created by workers. It is therefore quite useful to any capitalist system to build a common sense understanding that wealth is a private — not social — creation, the end result being that the working classes consent to the private control of wealth and the means of production. Homeownership, as the primary point of contact between speculation, asset-building and wealth creation for Americans from all socio-economic and racial backgrounds, is central to the construction of this ideology.

Domestic Bliss or Patriarchal Domination?

As Silvia Federici, Angela Davis, and legions of Marxist feminist scholars have argued, the unpaid reproductive and domestic labor performed by women in the home is essential to the reproduction of capitalism. In the words of Federici: “the exploitation of women has played a central function in the process of capitalist accumulation, insofar as women have been the producers and reproducers of the most essential capitalist commodity: labor-power.” Engels, in his landmark book The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State, powerfully links the development of private property and the patriarchal family unit, arguing that capitalism necessitates a union of the two in order to function.

Therefore, the ideological centering of homeownership as the site of domestic bliss and family life serves a very material purpose within US capitalism. Mass homeownership carries with it deeply held cultural beliefs about women’s role in society, specifically that women should be confined to their private homes in order to carry out the domestic labor and the duties of social reproduction. Of course, the significance and character of these meanings have changed over time. In the 1920s, when Hoover and his ilk were propagandizing the virtues of the owned home, they were responding directly to radical anarchist and Bolshevik ideas about reproductive freedom, free love and women’s labor. Homeownership was indelibly tied to the idealized vision of a (necessarily white) breadwinning father, domestic mother and obedient children. In the post-war period, domestic work was cast as a patriotic, anti-communist duty, coinciding with the rising prominence of homes-as-assets. As Gonzalez writes, “the home became not only the commodity which physically contained all the others, but was also a worker’s main asset — the commodity for which all others were sold, and eventually the one which also purchased all the others.”

In contrast, in the 1970s, as Black women became the targets of “predatory inclusion” and the unwitting owners of crumbling, debt-laden homes, their role as caretakers of these homes was emphasized in order to lay blame at their feet instead of with HUD and the structurally racist real estate industry. The mass media and government officials consistently emphasized the irresponsible nature of Black female homebuyers, creating, in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s words, a “dysfunction discourse” that helped engineer the persistent moral panic about the state of Black inner cities in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Building on Mark Fisher’s concept of capitalist realism, Helen Hunter argues that “domestic realism” — wherein “the isolated and individualized small dwelling (and the concomitant privatization of household labor) becomes so accepted and commonplace that it is nearly impossible to imagine life being organized in any other way,” serves to reinforce gendered hierarchies and divisions of domestic labor. The practice of mass homeownership reifies the domestic sphere — a crucial site to imagine, reinvent and revolutionize gender roles in a collective and egalitarian manner — as the natural, post-ideological arrangement for social reproduction.

I’m not the person to sketch a socialist feminist vision of housing, but such a project certainly includes a radical break with the unpaid domestic labor in the home which is central to the ideology of homeownership. It is almost certainly a vision that demands cooperative, socialized domestic work and compensation for previously unpaid domestic labor. It is also almost certainly a vision that is incompatible with mass private homeownership, which necessarily confines domestic labor to the individual home, rather than socializing domestic labor.

Black Homeownership and The American Nightmare

There are two histories of homeownership in the United States: white homeownership, and homeownership for everyone else. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, author of the essential Race for Profit, puts it best: “The quality of life in U.S. society depends on the personal accumulation of wealth, and homeownership is the single largest investment that most families make to accrue this wealth. But when the housing market is fully formed by racial discrimination, there is deep, abiding inequality.”

In its modern form (roughly from the 20th century onwards), the public policy and propaganda supporting homeownership have been intentionally constructed to benefit white families. Hoover’s propaganda campaigns in the 1920s and 30s always depicted white families as the ideal, patriotic, capitalist homeowners. In the New Deal and post-war eras, subsidies for homeownership were granted to white families and excluded Black families. Redlining, restrictive covenants, and mob violence all kept neighborhoods segregated and severely devalued Black homes throughout the mid-20th century. When homeownership financing was finally extended to Black families en masse in the 1970s, it was structured in order to reap profits for realtors — in stark contrast with the white-wealth building intent of previous government homeownership programs. Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, Black homeowners were pulled into the maelstrom of debt-fueled neoliberal capitalism in order to be exploited by subprime loans and Wall St chicanery. The nature of the racially exploitative housing market was made clear once again in the aftermath of the 2008 housing crash, as Black families were disproportionately impacted by foreclosures and subprime loans. The racial wealth gap widened in the aftermath of the crisis.

In 2021, 75.8% of white families owned their home, compared to just 46.4% of Black families. In 2019, the median white family was worth $188,200 while the median Black family was worth just $36,100. The racial wealth gap is an undisputable legacy of chattel slavery, redlining and Jim Crow capitalism. It is one of the clearest expressions of the structural deficiency of the American Dream.

And yet, even as it is widely acknowledged on the liberal-left wing of the American political spectrum that unequal access to wealth-building through homeownership is at the core of the racial wealth gap, analysts consistently suggest further investment in homeownership as the only possible solution to the problem. For instance, in their highly influential 1995 work, Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality, Oliver and Shapiro lay out, in extensive historical detail, the processes by which Black communities have been denied access to wealth-building through homeownership and then go on to argue that individualized asset-based welfare systems — primarily operationalized through homeownership — are a promising potential solution.

Major liberal think tanks like the Brookings Institution or the Urban Institute will write extensively about the long history of racial exclusion from homeownership, and then conclude definitively that the only logical solution is to “ensure that millions of credit-worthy black renters can gain access to stable, affordable, and safe homeownership” and “improve opportunities for potential Black homebuyers and reduce the racial wealth gap.”

In 2020, Bernie Sanders ran on probably the most left-wing housing platform attributable to a popular, major party, presidential candidate in decades. He advocated for reinvesting in public housing, cracking down on racial discrimination and expanding community land trusts. Still, he argued that “the American dream of homeownership is simply out of reach,” and therefore “we need to substantially expand federal programs to make sure that Americans throughout the country have the ability to buy their first home.”

Rather than look to egalitarian horizons wherein racist private property relations are dismantled and land is redistributed — rather than challenge the notion that Americans should be constantly interpellated as consumers and speculators — further investment in capitalism is argued to be the only solution to the problems created by hundreds of years of capitalist exploitation.

As Taylor writes, this outlook belies a “magical belief that homeownership will ever be a cornerstone of political, social, and economic freedom for African Americans.” It is a core component of the ideology of Black Capitalism, which James Baldwin once described as “a concept demanding yet more faith and infinitely more in schizophrenia than the concept of the Virgin birth.” While the methods of extending homeownership opportunity may be critiqued, the underlying assumptions — that individual asset accumulation through homeownership is the key to social mobility and that private property (the basis of the US settler-colonial nation-state) is an inevitable feature of human social organization — are rarely, if ever, questioned.

Conclusions

I would argue that, even for most contemporary left activists and movements who do act on a theory of change grounded in a systemic analysis of US capitalism, it is typically seen as pointless to waste energy trying to contradict a deeply held American value like homeownership. The project of outright rejecting private homeownership is either considered not politically expedient or not considered at all.

I don’t want to discount that the ideological terrain has shifted in the US left housing movement, especially since the 2008 housing crash. There has been an increasing emphasis on social housing, as exemplified by popular proposals like the “National Homes Guarantee,” or the Peoples Policy Project’s “A Plan to Solve the Housing Crisis Through Social Housing.” In these plans, private, speculative homeownership takes a backseat to decommodified, socialized conceptions of home and housing. In “The National Homes Guarantee,” the authors refer to homeowners as “bank tenants,” highlighting an increasingly mainstream skepticism about the liberatory promises of homeownership. In the past few years, the community land trust and cooperative housing models have gained prominence in cities and rural areas alike to combat rising housing costs, gentrification and speculation. The wave of insurgent tenant movements spurred on by the COVID-19-induced housing crisis and rising consciousness of private homeownership’s exploitative nature in the wake of the 2008 housing crisis also provide important context.

However, these developments alone do not constitute an intentional, counter-hegemonic, ideological thrust against homeownership and the American Dream. Socialized housing, after all, if promoted like many other goals of the US left — that is, alongside their antagonists — will always maintain a subordinate position. It is ultimately unproductive to shirk from direct confrontation with the ideology of private homeownership, in the same way that it is unproductive to argue for expanded public transit while refusing to attack highway funding or to argue for the deployment of renewable energy without tackling the systemized overconsumption at the root of the climate crisis.

So, despite the promising emergence of more radical challenges to the ideology of homeownership, the promotion of homeownership as a cure to wealth inequality, racial inequality and other social ills remains a near-hegemonic line of thinking. The acceptance of this thinking is fundamentally naive. It is naive to view private homeownership as a neutral concept, one that we can pluck from history and promote uncritically in the present day, while ignoring its historical role in maintaining race, gender and class domination. A continued uncritical embrace of homeownership in the rhetoric and praxis of the left — and in particular, the discourse which argues that homeownership can be a tool of social justice through wealth accumulation — does little to “destroy the appearance of a natural order.” Rather, it reinforces the common sense understanding that wealth should be built and controlled individually, that individual advancement is a preferable alternative to collective power-building, and that private property relations should reign supreme.

Fundamentally, the ideology of homeownership disseminates and enforces the ideology of the ruling class and undermines any discussion of overturning private property relations. As a result, as the ever-relevant W.E.B. DuBois’ wrote, the US is “not simply fundamentally capitalistic,” — it has “no conception of any system except one in which capital was privately owned.” Homeownership, particularly within the neoliberal cultural hegemony that still holds so much sway over our lives, helps preclude the possibility of a collective political subject and instead interpellates each of us as consumers, speculators, and market subjects above all else. For women, private homeownership continues to promote a domestic-centered lifestyle, consigning them to do unpaid and underappreciated work. For poor immigrants, Black communities, women, and other economically marginalized groups, homeownership is central to the endurance of the American Dream, inducing buy-in to the system of US capitalism by arguing that anyone can make it in America — and if you fail, it’s your fault.

. . .

The urban rebellions which gripped the nation and incited a genuine ruling class crisis in the summer of 2020 illustrate that, despite what the suffocating, “pervasive atmosphere” of late capitalism may lead us to believe, it is indeed possible to smash common sense ideology like that of homeownership. The spontaneous rebellions which broke out in Minneapolis and spread quickly across the country thrust us headfirst into a radical political moment, where the shackled horizons of neoliberal capitalism melted away in the face of a mass movement.

The various abolitionist currents and slogans present in May of 2020 went through complex processes of creation, co-option, revision, and moderation. But fundamentally, what emerged on the other side of the rebellions was a popular, revolutionary, if fractured, horizon. The ideology foundational to the neoliberal carceral state and its self-conception of social order — that social ills (particularly in Black and brown communities) cannot be solved through social and economic restructuring, but must instead be met with the violent force of prisons and policing — has become contested terrain. Many people who just weeks before the rebellions would scoff at the sheer lunacy of abolishing prisons or the police were suddenly proselytizing about the social causes of crime and the true role of the police and prisons in protecting property, whiteness, and US racial capitalism.

I don’t mean to romanticize the moment. What I want to emphasize is that radical horizons are possible only if we challenge the entrenched common sense understandings that undergird US capitalism — and crucially, that a large part of the ideological success of the abolitionist movement last summer was due to their preparation. Organic intellectuals like Mariama Kaba, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Angela Davis, and organizations like Critical Resistance and Black Lives Matter, had been building the foundations of an abolitionist movement for years and were therefore prepared to seize the moment. Contrast that with the extremely fractured and weak state of the US left during the 2008 financial crisis, where the left — and the housing movement in particular — was ill-prepared to offer a systemic critique of homeownership, the American Dream, and neoliberal capitalism more broadly.

Homeownership must be connected to the broader political economy and ideology of contemporary capitalism. We need to assert that US capitalism’s ideological permanence draws strength from and is reproduced by housing systems and private homeownership in particular. What does this specifically entail for the left housing movement in the US?

We need a politics of housing that attacks capitalism at its roots in private property relations. A counter-hegemonic housing movement must be rooted in a radical turn towards socialized land, communal domestic labor and decommodified housing. Rather than continue to center private homeownership as the route toward social progress, we must reject private homeownership and embrace democratic, tenant-controlled social housing models like community land trusts, cooperative housing, Native American communal land holdings and public housing. Importantly, we have to actively work against the common sense understanding — which has been reinforced through the very real experiences of eviction, landlordism and poor housing quality within the rental market — that security of tenure, personal space and realization of citizenship can only be achieved through homeownership.

Through this radical break with the ideology of homeownership we can assist in forging a revolutionary common sense understanding, one which argues that:

- the American Dream is a farce that only serves to reinvest potentially revolutionary energy back into the system;

- private property is inherently violent and anti-egalitarian;

- wealth is socially created and therefore should be socially controlled;

- poverty is endemic to capitalism, not individuals;

- domestic labor should be socialized and women should not be consigned to unpaid labor in the home;

- the persistence of a permanent, racialized underclass of the unemployed, drug addicts, “criminals” and homeless people is a consequence of systemic failure, not individual deficiency;

- and in the final analysis, we are members of a collective subject that can and must organize for our collective present and future.

I neither have the space nor the wisdom to offer a concrete vision of what this actually looks like. This article is intended to be a suggestive intervention, a critique on the terrain of ideology. But, as Paulo Freire reminds us, praxis is more than critique. Praxis is “reflection and action upon the world in order to change it.” This is just a reflection — an important one, I believe, but one that means very little until it is translated into action.

One important and concrete step we can all take towards building this new politics is to join and commit ourselves to principled, revolutionary tenant organizations. I organize with Brooklyn Eviction Defense, a communist, autonomous tenant organization. Through a variety of tactics, we help stop evictions (legal and illegal, because all evictions are violent and unjust, regardless of whether the state has sanctioned them), intervene in cases of landlord harassment, help tenants organize their buildings and much more. Our organizing work is rooted in a material struggle against the everyday violence of private property and the intertwined ideological struggle to activate a revolutionary tenant consciousness. We struggle daily against entrenched common sense understandings of homeownership and private property. We believe it is critical to hold a strong political line in favor of abolishing rent and private property. We are far from perfect, but our commitments give me hope that through principled struggle, we can smash the old politics of housing and forge a new, revolutionary common sense.