When people think of the casualties of the 1950s anti-comic book crusade, EC comics is foremost amongst them. I’m guilty of this particular sin myself, as when I wrote my article "When Comic Books Threatened the U.S.A. and the World," the bulk of the text focused on EC comics and the backlash against them. But, there were other publishers that fell victim to the comics purges as well, including one with a definite connection to the American Left: Lev Gleason Publications, the company that produced such titles as Boy Comics, Daredevil Comics, and the infamous Crime Does Not Pay.

Born Levrett Stone Gleason in 1898, the company’s namesake publisher came from a prosperous Protestant Massachusetts family with a background in progressive causes. For instance, Gleason’s maternal grandfather, after whom he was named, Leverett G.E. Stone, had founded the abolitionist movement in both border states of Ohio and Kentucky. His paternal grandfather Dr. Aaron Gleason was a U.S. Army surgeon during the Civil War and provided free treatment to Black veterans after the war. Gleason attended Andover and Harvard before dropping out to serve in an artillery unit during World War I.

After the war he worked as a stockbroker before becoming advertising manager at Eastern Color Printing in 1933. This company printed color sections of comics for the Sunday editions of East coast newspapers such as the Boston Globe. Eastern Color is famous for producing the first color comic books, reprints of the newspaper comics with titles like Funnies on Parade and Famous Funnies. The latter was the first color comic to be sold commercially, for a dime in 1934. In 1936 Gleason became editor of Tip Top Comics, a title that repackaged United Features comic strips in book format. As editor, he made the historically unwise decision to reject Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman, calling the concept “an immature piece of work.” The duo then took the idea to Action Comics.[1] By 1939, Gleason was ready to strike out on his own in the comics industry. He partnered with Arthur Bernhard to found Silver Streak comics and hired writer-artist Jack Cole to edit this magazine. Bernhard soon left the publication, which had difficulty finding its footing in early issues, until the breakout Daredevil character (not to be confused with Marvel’s superhero of the same name) in issue 6 led to some success.

In addition to comics, Gleason was also involved in a number of left-wing publications. One of these was the left-wing tabloid Friday (later renamed Scoop for the final two issues) which had content similar to the newspaper PM but only lasted for twenty five issues. He published the magazine Reader’s Scope as a left-wing alternative to the right-leaning Reader’s Digest. Salute was a left-wing magazine published by Gleason aimed at returning veterans from World War II. He was also business manager, under the pseudonym Alexander Lev, of Soviet Russia Today, the monthly pictorial magazine of the group Friends of the Soviet Union. Sabotage: the Secret War Against America, an expose of American fascists and The Incredible Tito! were sample books that Gleason published, alongside his magazines. When he moved to Chappaqua, New York, Gleason set up the left-wing newspaper New Castle News to oppose the more reactionary local newspaper that already existed.

Lev got along well with his artists, frequently going out to eat and drink with them. He even set up a profit sharing arrangement with Charlie Biro and Bob Wood, in addition to allowing them to put their own names on comic covers, a rare practice at that time.[2] Gleason's sympathies were well known to his comics colleagues as well. One described him as a “liberal, almost left wing, politically committed kind of guy.”[3] Artist Pete Morisi, who worked for Gleason, stated “Everybody knew he was a Commie.”[4] Lev Gleason Publications was also a bit more racially diverse than most comics companies, employing several people of Japanese descent, including artists Bob Fujitani and Fred Kida, as well as letterer Ben Oda.

Despite his socialist idealism, Gleason also had a capitalist’s shrewdness. In the winter of 1941 he got a sweet deal on a few million pages of pulp paper, with the only caveat being that he had to have material ready to print by the following Monday. He told Charlie Biro that Friday to get sixty four pages ready over the weekend to be ready on Monday, with Daredevil as the star character. Biro worked together feverishly with Bob Wood, Bob’s brothers Dick and Dave, Batman artist Jerry Robinson, George Roussos, Mort Meskin, and Bernie Klein to draw and letter the comic during what turned out to be one of New York’s worst blizzards. The resulting comic, Daredevil Comics 2, was an artistic mess, as befits its difficult birth, but it paid off for Lev Gleason Publishing.[5]

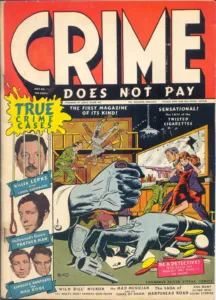

In 1942, Gleason asked Charlie Biro and Bob Wood to revitalize the sinking sales of Silver Streak comics. Biro claimed he was inspired by a real event in which he was approached by a man at a bar who offered him an “indiscreet rendezvous” with a woman. Biro turned him down but later learned in the paper that the man had kidnapped the woman.[6] This incident caused Biro to suggest a revamp of the title based on the exploits of real life criminals, called Crime Does Not Pay, named after a famous MGM documentary film series. At first, retailers were unsure on whether to display Crime Does Not Pay with the pulp novels or comics on newsstands and the title counted 700,000 sales monthly, making it only a modest hit. However, sales grew, eventually becoming so large that after the end of World War II covers of the magazine boasted “More than 6,000,000 Readers Monthly!” While the company was obviously counting on buyers of the comic to pass along copies to other readers in order to inflate this number, the actual sales were still formidable. Most industry accounts put the number sold at two million, but William Gaines, publisher of the rival EC Comics, put the number at four million.[7] This readership made Crime Does Not Pay a leader in the industry, even more popular than Captain Marvel and Superman. This success begat imitators with comically derivative titles like Lawbreakers Always Lose and Crime Must Pay the Penalty. Lev Gleason Publications even released its own cash-in called Crime and Punishment.

While Daredevil and other Lev Gleason Publication heroes like Pat Patriot obviously exuded Popular Front, antifascist values, whether Crime Does Not Pay carried any of its publisher’s politics is a subject of some debate. Gerald Jones states that the title “had a distinct political twist. Many of its stories delved into the hard, poor environments that had produced their subjects. The police rarely came off as admirable…”[8] Bradford Wright argues that the title’s propendorence of gold digging women who cajole men into crime made the series misogynistic, but that it also painted a hopeless picture of post-war America that was at odds with prevailing sentiment.[9] Colin Smith agrees that the title carried an air of nihilism, adding that the series showed that working in the capitalist system did not lead to rewards and that “the implication is always that the whites of apartheid America are corrupting themselves…Crime Does Not Pay still suggests that America had always been fundamentally corrupt…”

During his comic publishing career, Gleason remained involved with the American Left. While he was a registered Communist in the 1930s, he left after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between the Soviets and the Nazis for the more respectable American Labor Party. He chaired the Joint Anti Fascist Refugee committee, an organization set up to help refugees fleeing Franco during the Spanish Civil War. He was listed as a director of the People’s Radio Foundation, a proposed network of left-leaning FM radio stations. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell gave him a positive write up in his Black newspaper, the People’s Voice. In 1947 he contributed money to a Civil Rights Congress fundraiser designed to help defeat the racist Mississippi senator Theodore Bilbo. When President Truman gave his speech outlining his anticommunist Truman Doctrine, Lev Gleason wrote in the New Castle News “Are we going to police the whole world, attempt to shove our ideas down the throats of smaller peoples everywhere by force of arms?” When Truman signed Executive Order 9835 requiring a loyalty oath for all federal employees, Gleason denounced the measure as laying the ground for “potential fascism.” All the while, Gleason was under surveillance by the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover himself stressed the importance of keeping tabs on him due to both his political activities and his prominence as a publisher.[10]

In 1946, Gleason was grilled on his left wing activities by the United States House of Representatives and asked to name names from the by then-defunct Joint Anti Fascist Refugee Committee. Gleason refused and, along with sixteen others, was held in contempt of Congress.[11] He was given a $500 fine, and a three month jail sentence, which was suspended. Gleason may have made it through HUAC with his business intact, but the brewing anti-comics movement was coming for that as well.

In October 1948, the first comic book burning occurred in Spencer, West Virginia. The practice spread like wildfire to Chicago, Vancouver, and other cities. Burnings were sponsored by Boy Scout Troops and Catholic Archdiocese as a way to stop the spread of the “unwholesome” comic books. Particular attention was paid to crime and horror comics, but even Batman and Superman ended up on pyres across the country. Alongside the burnings, legislative efforts were introduced to ban comics. LA County passed a comic book ban in 1948, soon joined by Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. The state of New York almost banned comics in 1949, but Governor Dewey vetoed the measure. Throughout, Gleason attempted to fight these measures. When Chicago’s police commissioner ordered Chicago comics distributors to stop circulating Crime Does Not Pay after arguing the book was indecent, Gleason successfully filed an injunction at the Illinois Superior Court.[12] During the debate over the attempted ban in New York, he wrote a scathing letter to the New York Times that attacked those who would “set up an intellectual dictatorship over the reading habits of the American people.”

Gleason's erstwhile allies on the American Left had turned against comics just as much as the ruling class had. In the Communist Party’s Daily Worker it was argued that comics were “brutalizing American youth to prepare them for military service in implementing their government’s aims of world domination.” When Gleason suggested in 1952 that American comics should be sent to the Soviet Union as a symbol of American-Soviet friendship he was ridiculed by the left-wing National Guardian who claimed that American comics were “pseudo-scientific” and “instigators of juvenile crime in America.” Overseas the French and British Communist Parties rallied against comics and pushed for bans on “degenerate comics” from America.

When Psychiatrist Frederic Wertham wrote Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, it marked the most serious assault against comics yet. Excerpts from Wertham’s book, in which he blamed comics for inspiring real life violence in children, were reprinted in popular periodicals like the Ladies Home Journal. Wertham was allegedly a follower of the Frankfurt School Marxist Theodore Adorno and advanced a similar critique of mass culture. In some ways, the conflict between Wertham and Gleason’s approach to the media is symbolic of the gap between New and Old Lefts. Gleason was a populist, convinced that mass media, particularly print, could promote justice, tolerance, and other moral virtues. Wertham on the other hand, saw mass media as a threat that the supposedly ignorant hoi polloi had to be protected against by the intellectual elite.

In 1954, the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held a public hearing in New York City at which Wertham was the star witness. At the hearing Wertham claimed that “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.” Gleason asked to appear as a witness, but his request was denied. Instead, EC Comics’ Bill Gaines appeared and attempted to explain the social and entertainment value of his comics to Senator Estes Kefauver et al. At the turning point of the hearing, the Subcommittee brought up an illustration of a decapitated corpse from Crime SuspenStories 22 and Gaines weakly claimed that the cover was “in good taste” for a horror comic.

In the aftermath of the hearing, the comics industry set up the Comics Code, another attempt at self-censorship to ward off the government. The rules of this code were much stricter and spelled the end for titles like Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay and EC’s Vault of Horror. Prohibited were the words “horror” and “terror” as a part of titles, and the word “crime” could no longer be larger than other words on a cover. Stories now had to show good always triumph over evil and were scrubbed clean of violence or disrespect for established authority. Crime Does Not Pay was canceled in 1955 and Lev Gleason Publications itself went out of business in 1956, two years after the code was established.

Bob Wood, who helped make Crime Does Not Pay such a success became a participant in his own true crime story. In 1958, he was arrested for killing a woman during a drunken argument and received three years in prison for manslaughter. Upon his release, he was rearrested for a parole violation. He was finally released for good in 1966, before dying in a traffic accident six months later.[13] Charlie Biro ended up working as a graphic artist at NBC until his passing in 1972. Bob Fujitani continued to work in comics on characters like Flash Gordon. Carmine Infantino and Joe Kubert, who did occasional work for Lev Gleason Publications, went on to greater fame at DC Comics. George Tuska, the artist on dozens of issues of Crime Does Not Pay, spent ten years as the artist for Marvel’s Iron Man.

In the aftermath of his exit from the publishing industry, Lev Gleason began selling real estate and patriotic ornaments in Chappaqua. He later retired to Cape Cod. For the 50th anniversary reunion of his Harvard classmates in 1970 he wrote “My greatest satisfactions have been doing what I can politically to make ours a better country and the world a little more peaceful. I have been strongly opposed to the Vietnam War since the outset. And I do hope for better things. Probably because of the efforts of today’s youth, especially the militant ones, who have more guts than we had.” Leverett Stone Gleason passed away in 1971. Those who want to learn more about his pioneering life are encouraged to read American Daredevil: Comics, Communism, and the Battles of Lev Gleason, written by his nephew Brett Dakin.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Gerard Jones, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book (New York: Perseus Books Group, 2004), 119. ↩

- Ibid, 193. ↩

- Bradford Wright, Comic Book Nation: the Transformation of Youth Culture in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 43. ↩

- David Hadju, The Ten-Cent Plague: the Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America (New York: Picador, 2009), 107. ↩

- Jones, 187-188. ↩

- Nicky Wright, “Seducers of the Innocent: the Bloody Legacy of Pre-Code Crime Comics,” Comic Book Marketplace 65 (1998). ↩

- Dennis Kitchen, “Biro and Wood: Partners in Crime,” Blackjacked and Pistolwhipped: a Crime Does Not Pay Primer (Portland: Dark Horse Books, 2010), 10. ↩

- Jones, 194. ↩

- Wright, 83-84. ↩

- Paul S. Hirsch, Pulp Empire: the Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2021), 163-164. ↩

- Ibid, 162-163. ↩

- Wright, 100. ↩

- Kitchen, 20-21. ↩