Noel Ignatiev was a life-long revolutionary. Treason to Whiteness is Loyalty to Humanity, is a collection of 43 of his essays written over a span of 52 years. The selection focuses on his ideas about white supremacy, as well as revolutionary organization and strategy. It also shows how his thought developed from the heady days of the 1960s through 2019, when he passed away. The book is organized into four sections reflecting various periods of Ignatiev’s life, but also the conditions he was confronting as he wrote these essays. Preceding each of the 43 short essays is an editor’s note on the year and context in which they were written. This review will focus on his ideas and his activism confronting the system of white supremacy and his insistence that revolution must begin with the elimination of the “white race.”

By the time I met Noel in the early 1970s, he had been in and out of the Communist Party (CP), a CP split off group called the Provisional Organizing Committee (POC), and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). He was also one of the founding members of Sojourner Truth Organization (STO). I met Noel when I joined STO. But before I joined I was already familiar with the open letter Noel and Ted Allen wrote called White Blindspot (p. 44). The essay was part of ongoing discussion within SDS that attacked the Progressive Labor Party’s position on the “Negro liberation movement” on the ground that it “places the Negro question outside of the class struggle.” In White Blindspot, Ted Allen brought with him an insight from his historical studies of early slavery in the U.S. where, he argued that the white race was invented as an incentive to non-African workers, enticing many to join their capitalist oppressors rather than make common cause with black slaves. Noel developed his analysis based partly on his studies of history, especially the Abolitionist Movement, the Civil War, and Reconstruction period. He was greatly influenced by W.E.B DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, which is referenced in a number of the essays included in this collection. In addition, he studied and admired the activities of a number of leaders of the abolitionist movement, especially John Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips.

But White Blindspot, as well as a number of essays that developed its ideas further, was also based on Noel’s experiences working in factories for 20 years. It was in the factories that he witnessed firsthand the white skin privileges they refer to in White Blindspot. Noel, at that point in his life, identified himself as a manufacturing worker. Ted Allen went on to write the two-volume history called The Invention of the White Race. Noel wrote a number of essays and polemics that extended the arguments of White Blindspot such as “Learn the Lessons of U.S. History” (p. 61) which was first published in the SDS journal “New Left Review,” as well as “Black Worker, White Worker” (p. 97), and a speech he gave in 1976 titled “Theses on White Supremacy” (p. 115).

When I met Noel in the 1970s he was working in the blast furnace division of U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana which he termed “the largest division of the largest works of the largest steel mill in the world.” Prior to that, he had done many years of manufacturing work in a variety of industries, spending 20 years in manufacturing altogether. These experiences in manufacturing contributed greatly to his ideas about white supremacy. His political approach to his work in factories represented an effort to practice the ideas laid out in his writings.

U.S. Steel’s Gary Works was located in a region that included Southeast Chicago and Northwest, Indiana. In 1970, that region included one of the largest concentrations of heavy industry in the world. In addition to Gary Works, the region was anchored by nine other steel mills, which at their peak, employed a total of 200,000 workers. It has been estimated that for every steel job in the region there were seven other manufacturing workers, bringing the total manufacturing employment to over one-and-a-half-million workers. The presence of the Lake Michigan ports, rivers that served industry, railroad spurs, highways, and the mills themselves attracted firms that manufactured steel products like automobiles, railroad cars, and steel structures. It also attracted industries that supplied products to the mills and to other factory workers—chemicals, processed food, tools, work boots, and welding equipment.

What was true of Southeast Chicago/Northwest Indiana was true throughout the Chicago Metropolitan area and large cities throughout the nation. Manufacturing was the center of the U.S. economy. In the U.S. in 1970, 22% of workers were employed in manufacturing. Black workers were largely excluded from the most skilled manufacturing jobs. Their initial entry into the Northern industrial labor force had been resisted by companies and unions alike. And once they became part of that labor force, they were restricted to the lowest paid and most dangerous jobs. Unions aided and abetted that process and hence were participants in the development of modern white skin privilege. In “Learn the Lessons of U.S. History,” written in 1968 Noel writes:

White supremacy is a deal between the exploiters and a part of the exploited, at the expense of the rest of the exploited—in fact, the original sweetheart deal.

As black labor gained a foothold in manufacturing, especially in large industries like steel, auto, meatpacking and heavy equipment, the great Civil Rights Movement, including urban rebellion in black neighborhoods, began to spread to the workplace. Black workers began to challenge white skin privileges at the point of production. And more often than not challenged the union itself which had been complicit in establishing those privileges. In the steel industry where Noel worked the seniority system had been adapted to ensure that most black workers remained in the most dangerous and dirty jobs. As Noel notes in “Black Worker, White Worker,”

Through a fairly involved process, seniority has been adapted to serve the needs of white supremacy.

Following the lead of black workers, Noel’s practice and his writings attacked this adaptation of the seniority system in steel and other aspects of white supremacy at the point of production. Simultaneously, white skin privileges of all sorts were challenged throughout the nation by a variety of black organizations at workplaces and in communities. The rise of black caucuses in manufacturing were an inspiration and a call to action for Noel and all of us in STO.

In 1979, Noel left Gary Works and worked at some other factory jobs until he decided to return to the university in 1984. He had time to reflect on his 20 years as a manufacturing worker and continue his study of history. The result was the book How the Irish Became White. In the introduction to that book we see a shift in his emphasis regarding the system of white supremacy from whites refusing to accept white skin privileges to the abolition of the white race itself. Abolition of the white race had always been part of Noel’s argument of how to combat white supremacy, but in his writings in the 1980s and 90s, this became the main emphasis.

In How the Irish Became White this emphasis is laid out in the introduction (p. 230):

The white race is a club. Certain people are enrolled in it at birth without their consent, and brought up by its rules...When it comes to abolishing the white race, the task is not to win over more whites to oppose racism…The task is to gather together a minority determined to make it impossible to be white. It is a strategy of creative provocation, like Wendell Phillips advocated and John Brown carried out. (This minority) would have to break the laws of whiteness so flagrantly as to destroy the myth of white unanimity.

A sharp distinction is made between “anti-racism” and abolitionism. The latter involves an attack on all institutions that support and maintain “the club” of whiteness. Noel harkens back to the difference between anti-slavery and abolition. In two of the essays he uses the anecdote of William Lloyd Garrison burning the U.S. Constitution while calling for the abolition of slavery. He referred to this as an act of dual power.

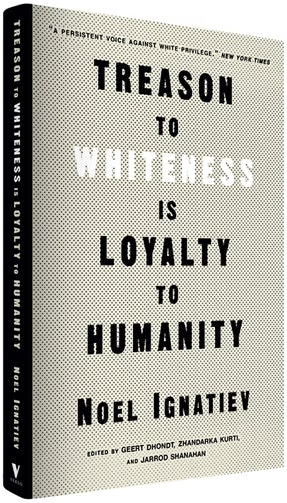

In 1993 Noel and his comrade John Garvey established the journal, Race Traitor, which they called a journal of the “new abolitionism.” Its motto was “Treason to Whiteness is Loyalty to Humanity,” which is the title of the present volume. Race Traitor was active until 2001. An entire section of the book is devoted to the Race Traitor project.

“New Abolitionism” didn’t come out of nowhere. Rapid developments in global capitalism and in U.S. society transformed the very nature of white supremacy, itself. Noel’s writing reflected these changes.

Beginning in the early 1970s there was a major shift in the way global capitalism produced, distributed, and accumulated value. New production technologies not only meant fewer workers employed in most industries but also enabled manufacturing of a single product such as autos to be pulled apart and produced in different places. Transportation and logistics technologies such as big box containers, and computerized inventory controls enabled manufacturers to ship parts, raw materials and finished products across the world. New institutional arrangements in the form of “trade agreements” that included finance erased all barriers to the global movement of capital, goods, and services. Capitalism, for a time, thrived through the construction of huge and complex supply chains that gave rise to a new logistics industry enabling large corporations to roam the world in search for the greatest profits.

The result of these developments in all industrialized countries included a sharp decline in manufacturing employment. In the U.S. the percentage of the workforce employed in manufacturing dropped from 22% in 1979 to 9% in 2019 – about eight million jobs. Black and brown people suffered the greatest losses. Prospects for living wage jobs among black youth without a college education declined to practically nothing. The once mighty Southeast Chicago/Northwest Indiana region where Noel worked suffered a massive decline. Eight of the ten steel mills in the area were closed altogether and the remaining mills were able to produce more steel with a fraction of the workers. Between 1979 and 1989, net manufacturing job loss (jobs lost minus jobs gained) was 128,986, representing a decline of 36%.

Insurgencies at the point of production in the U.S. temporarily ceased as did factory organizing work for people like Noel and his organization, STO. The work of combating white supremacy by being a race traitor had to take a different form.

But there was more. The revolutionary potential of the civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S. was contained by opening up positions that had once been reserved for whites to black and brown people. This essentially sharpened class divisions within black and brown society and in fact eroded white skin privileges themselves. From the election of Harold Washington as the first black mayor of Chicago in 1984 to Chicago’s Barack Obama becoming the 44th President of the United States in 2009, the myth that race was no longer a barrier to full participation in U.S. society became widespread. Black people were no longer barred from positions of power in corporate America. Cops, firemen, all sorts of government officials including school administrators were areas now open to a range of “people of color.” Noel reflects on these in the essay “Race or Class” (p. 367), which was written sometime after Obama’s reelection in 2012.

The triumph of the civil rights movement gave rise to a layer of black people, north and south, whose job is to administer the misery of the black poor, often in the name of “Black Power.”

I am not suggesting that the privileges of whiteness no longer exist; but changes in the economy and the decline of many institutions that used to guarantee them…mean that they are no longer what they were.

Neither the dramatic changes in the political economy nor the nature of the changes in white skin privileges referred to in the above essay were really emphasized during the Race Traitor period. Noel and John Garvey fully acknowledge this in their essay “Abolitionism and the Free Society” written in 2001 as an assessment of Race Traitor and its neo-abolitionist project (p. 249):

We were unprepared for the emergence of the new anti-globalization movement and have found ourselves to be relatively insignificant external communicators on its strengths and weaknesses.

We were also unprepared for the extent of the erosion of white privilege and the concomitant appearance of blacks in positions of authority within traditionally white-dominated institutions.

Yet the emphasis on the need for a neo-abolitionist movement meant that Race Traitor and the subsequent project of the journal Hard Crackers that Noel was working on at the end of his life was addressing some of the fallout of these developments.

One of these was the rise of “whiteness studies” in academia. Noel reacted quite sharply attacking those who would make a category of “whiteness” and attempt to find “the good qualities of white people.” Noel offers his attack in essays written in 1997 “The Point is not to Interpret Whiteness but to Abolish It,” (p. 233) and 1999 “Abolitionism and the White Studies Racket” (p. 241):

Now that White Studies has become an academic industry, with its own dissertation mill, conferences, publications, and no doubt soon its junior faculty, it is time for abolitionists to declare where they stand in relation to it. Abolitionism is first of all a political project: abolitionists study whiteness in order to abolish it…

Various commentators have stated that their aim is to identify and preserve a positive white identity. Abolitionists deny the existence of a white identity.

By defining abolitionism and contrasting it to both anti-racism and whiteness studies, the Race Traitor project laid the ground for battling perhaps a new form of white skin privilege which is the privilege of not joining blacks as the primary residents of the prisons and the primary victims of police violence. White supremacists mobilize on the ground that white people must fight to not be replaced by people of color and by stoking a fear of whites being pushed to take the place of black people at the bottom of society.

The later essays in the book stress the need to abolish the white race by disrupting the institutions and practices that reproduce it (for example, the criminal justice system, the educational system, the labor market, and the healthcare system). These institutions now include both the police and the prisons. And it also includes fighting a rising and increasingly organized white supremacist movement. In a 2015 essay written with John Garvey, “Beyond Spectacle: New Abolitionists Speak Out,” (p. 310) they say:

…we insist that something like race still matters a great deal—as is perhaps self-evident during a period of time characterized by a spate of police murders of black men and the murderous assault in the Charleston church.

There are a number of other aspects of Noel Ignatiev’s body of ideas contained in this remarkable book. They include essays on revolutionary organization (he broke with Stalinist vanguardism) and revolutionary strategy that includes “the virtues of impracticality” and the notion of “dual power.” He reflects on the work of a number of individuals who influenced his thinking such as W.E.B. Du Bois, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, John Brown, C.L.R. James, and Ted Allen.

The essays contained here are useful not only to historians but as a guide to activists today who are continuing to develop a new abolitionist practice that focuses on the key institutions that facilitate today’s white supremacy – police and the prison system. Showing, as the book does, how Noel moves from the emphasis of White Blindspot to the neo abolitionism of his later writings in relation to changing objective and subjective conditions can be a guide to both the theory and practice.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.