The United States is a puzzle, in a sense the puzzle of the age. Its culture appears to be democratic. Dress is informal, waiters wear nametags and greet diners with a hearty “how ya doin’” as if they were old pals, and politicians are nonpareil when it comes to the fine art of shaking hands and kissing babies. Novelists like Washington Irving and Mark Twain pioneered a prose style that was clear, unpretentious, and user-friendly while the US has led the world in forging new types of popular entertainment from Hollywood movies to Broadway musicals. When it comes to individual freedom, America has often been at the forefront in terms of feminism, gay rights, and equal opportunity.

All of which suggests a democratic society in which relations are free, easy-going, and egalitarian. But America is at the same time intensely conservative. The Constitution, for instance, is a nightmare of inequality. The Electoral College is heavily weighted in favor of white rural states, the Senate is even more lopsided, while the House leans right due to rampant Republican gerrymandering at the state level. Yet there is no outcry, no clamor for change, no demands for structural reform. Indeed, thanks to an amending clause in Article V that requires massive super-majorities – two-thirds of each house plus three-fourths of the states – to change so much as a comma, the very idea of structural reform is barely understood. Instead of raging against constitutional immobility, Americans have made a virtue of it by turning the document into an object of reverence and devotion. They’re happy it’s untouchable because they think it renders it all the purer as a consequence. Rather than of society, the Constitution is above society rather like the heavenly cross that Emperor Constantine claimed to see on the eve of the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312, the one with the inscription, “Conquer in my name.”

The results are profoundly stultifying. But blaming the Constitution for the breakdown raises an all-important question: why did it arise in the first place? “The history of modern, civilized America,” Lenin wrote in August 1918, “opened with one of those great, really liberating, really revolutionary wars of which there have been so few.”[1] But if the revolution was really so liberating, why did it lead to a constitutional settlement that was so rigid and unresponsive?

The answer, pace Lenin, is that the American revolution was not a revolution at all, but in many respects the opposite.

To understand why, it’s necessary to take a deep dive into “the age of the democratic revolution,” as the historian Robert R. Palmer styled it in his two-volume work of the same title. Palmer’s monumental history of the period from 1760 to 1800 was published to great acclaim in 1959-64, but has since fallen into neglect. This is unfortunate because not only is it essential for anyone wrestling with the legacy of the French Revolution, but it’s essential for anyone wishing to understand the American Revolution as well. Palmer’s treatment is rich and dense, but his thesis can be neatly summarized: the French Revolution was so revolutionary that it revolutionized the concept of revolution itself. Afterward, the term would mean a great leap forward into something radical and new. But, previously, it had meant the opposite, i.e. a process of revolving back to some pristine era in the past.

This was true for nearly the entire west on the eve of the great transformation of 1789. In Holland, the “patriot movement” stood “for ‘restoration’ of an older and freer Dutch constitution,” Palmer writes. In neighboring Belgium, a Hapsburg possession since the 14th century, a “revolution against the Enlightenment” arose around the same time in response to efforts by Austrian Emperor Joseph II to modernize the country’s political structure by improving the status of non-Catholics, reducing trade barriers imposed by towns and guilds, reining in medieval seigneurial courts, and shutting down large monastic estates. At least one sector of the Belgian ruling class opposed such top-down reforms on the grounds that it was the same late-medieval tangle of customs, guilds, and complicated governing structures that protected freedom against the “enlightened despotism” represented by the emperor.

The same was true in Switzerland where “rural, upland, ‘primitive,’ and ‘democratic’ cantons … governed themselves through folk-meetings attended by all grown men.”[2] It was true in England where people referred to the 1640s as a rebellion and reserved the term “revolution” for the very different events of 1688-89 when a Parliament dominated by the landed aristocracy rose to supremacy. It was true in France where, by 1787, the nobility was attempting to use aristocratic law courts known as parlements to turn back the clock to pre-absolutist days – to “a France,” as Palmer puts it, “in which the King ruled over a confederation of provinces, each guarding its own liberties and exemptions in taxes and administration, and each carrying on its own affairs through its own churchmen, its own nobles and gentry, and its own opulent dignitaries of the King’s good towns.”[3]

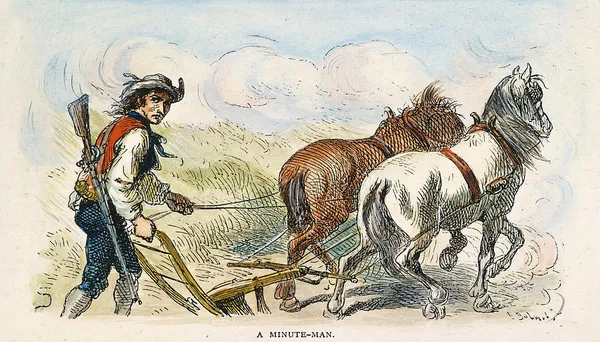

Freedom was safe when power was dispersed and protected by ancient traditions and customs. Finally, the politics of nostalgia held true in British North America where settlers equated liberty with old-fashioned colonial assemblies and town meetings. Indeed, such attitudes were especially pronounced since, for the bulk of the population, the past really had been a golden age. Colonial assemblies were “the most nearly democratic bodies to be found in the world of European civilization,” according to Palmer, governors rarely wielded the royal veto, while “the level of wealth was higher than among corresponding classes in Europe.”[4] External coercion was meanwhile minimal. When Boston erupted in riots in 1747 over attempts to “impress,” or draft, sailors along the waterfront, the royal governor, a British army officer named William Shirley, called out the militia to restore order. But as Stacy Schiff notes in her new biography of Samuel Adams, he quickly “discover[ed] that the mob and the militia – officially every man between the ages of sixteen and sixty – were one and the same.”[5] If Bostoners wanted a riot, there was thus no way to stop them, which is how the colonists thought it should be. Americans were de facto self-governing long before they were de jure.

Prosperity, equality, and local self-rule were all of a piece. But the Seven Years’ War of 1756-63 was the great turning point. The war pitted France and Britain against one another across five continents and left both countries on the verge of bankruptcy. Both were therefore desperate to put their affairs on a new footing. For the British ruling class, the solution seemed clear. After decades of allowing the colonies to go their own way, it was time for them to ante up by submitting to revenue-raising measures imposed by Parliament, the imperial command center. There was no question that the colonists should pay given the high level of wealth and the fact that smuggling was so rampant. Forcing them to do so was the rational thing to do. But however justified, top-down reforms like these struck Americans the same way that they would strike Belgians a couple of decades later, which is to say as an assault on ancient liberties.

The famous portrait that John Singleton Copley painted of Samuel Adams in 1772 says it all. It shows Adams looking firm and resolute in a plain russet coat as he points to the royal charter that had established the Massachusetts Bay Colony back in 1629. This was the charter, signed by Charles I, that promised that settlers “shall have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects … as if they and every [one] of them were born within the realm of England.” Since self-government was the most important liberty of all, taxation from afar was at odds with the ancient grant and hence null and void.

Belgians employed the same logic in opposing Joseph’s reforms on the basis of a similar charter of liberties, the so-called Joyous Entry, that the Hapsburgs granted in 1356. The Swiss did the same in citing the Eidgenossenschaft, or oath pact, that a handful of Alpine cantons had supposedly entered into in 1307. Legal precedent was of the essence. But the French Revolution did the opposite. Law was on the side of the nobility, which had used its ancient liberties to oppress the third estate. Hence, French revolutionaries set out to abolish legal precedent by giving democracy free rein in the here-and-now. When the new French national assembly did away with feudalism in August 1789, it did so not on the basis of pre-existing law, but on the basis of new law that it made up on the spot. “The National Assembly abolishes the feudal system entirely,” it announced. “It declares that among feudal and taxable rights and duties, the ones concerned with real or personal succession right and personal servitude and the ones that represent them are abolished with no compensation.” The assembly didn’t care about legal precedent because the old order was now kaput.

To be sure, Americans were also using language by this point that was fairly peremptory. “[W]henever any form of government becomes destructive … it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it,” the Continental Congress declared in 1776. “We the people … do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America,” the Constitutional Convention added in 1787.

Again, there was no invocation of precedent, no tortuous legal arguments, merely an assertion of democratic power in the here-and-now. But here the resemblance with France ended since the break with the past was far less complete. To quote Palmer:

Pennsylvania and Georgia gave themselves one-chamber legislatures, but both had had one-chamber legislatures before the Revolution. All states set up weak governors; they had been undermining the authority of royal governors for generations. South Carolina remained a planter oligarchy before and after independence…. New York set up one of the most conservative of the state constitutions, but this was the first constitution under which Jews received equality of civil rights – not a very revolutionary departure, since Jews had been prospering in New York since 1654. The Anglican Church was disestablished, but it had had few roots in the colonies anyway. In New England the sects obtained a little more recognition, but [Puritan] Congregationalism remained favored by law. The American revolutionaries made no change in the laws of indentured servitude. They deplored, but avoided, the matter of Negro slavery.[6]

Power was in the people’s hands, yet they used it to preserve the past rather than change it. And why not? The past was good; it was change that sowed the seeds of tyranny. To be sure, independence required Americans to change to a degree. But still, they resisted as much as possible. Where the French sought to concentrate the new democracy in an all-powerful revolutionary government, the Americans did the opposite by hedging it about with all sorts of legal restrictions. Despite decades of conflict between colonial legislatures and royal governors, they not only preserved the old conflict, but raised it to a higher level by pitting a national congress against a semi-monarchical presidency. Madison and Jefferson added another layer of complexity by drafting the Kentucky and Virginia state resolutions of 1798, which established that the states as a further counterweight. Not only would Congress, the presidency, and the federal judiciary check and balance one another, but the states would check and balance the new federal government while replicating the same three-way struggle in their own capitals.

Everyone would check and balance everyone else. Using the Latin phrase for divide and conquer, Madison summed up the approach in a letter to Jefferson a few weeks after the close of the Philadelphia convention. “Divide et impera, the reprobated axiom of tyranny, is under certain qualifications the only policy by which a republic can be administered on just principles,” he wrote. Self-division was the key to stability. Where Lincoln said that a house divided against itself could not stand, Madison said the opposite, i.e. that dividing it against itself was the only way to make sure it stayed up.

In effect, eliminating popular sovereignty would enable the people to rule. This is what made America a forerunner not of democracy, but of the very different doctrine of liberalism. This is a process by which a triumphant bourgeoisie not only casts off the revolution that enabled it to take power in the first place, but then creates a legal-ideological structure whose purpose is to banish the very idea. Revolution? What revolution? We don’t need no stinking revolution – such, in so many words, is the motto of the bourgeoisie as it seeks to deepen and extend its dictatorship. In Britain, the Victorians sought to banish revolution from history by writing off the Cromwellian interregnum as a brief deviation from a national tradition of compromise and moderation. In America, the task was all the easier by virtue of the fact that the country had never had a proper revolution in the first place. This was the problem that Tocqueville wrestled with in Democracy in America. Where the French had to pass through the revolutionary fires, Americans seemed to slip into democracy as effortlessly as if they were slipping into an old pair of slippers – which in a sense they were.

In 1842, a journalist caught up with a certain Captain Preston, the last surviving veteran of the Battle of Concord. “Did you take up arms against intolerable oppressions?” he asked.

“Oppressions?” the old man replied. “I didn’t feel them.”

“What, were you not oppressed by the Stamp Act?”

“I never saw one of those stamps. I certainly never paid a penny for one of them.”

“Well, what then about the tea tax?”

“I never drank a drop of the stuff; the boys threw it all overboard.”

“Then I suppose you had been reading Harrington or Sidney and Locke about the eternal principles of liberty?”

“Never heard of ’em. We read only the Bible, the Catechism, Watts’ Psalms and Hymns, and the Almanac.”

“Well, then, what was the matter? And what did you mean in going to the fight?”

“Young man, what we meant in going for those redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves, and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”[7]

In good pre-1789 fashion, revolution meant safeguarding ancient liberties while fending off change. The American Revolution was conservative because it sought to conserve liberties that lay in the past.

The events of 1776 and 1789 sent America and Europe off in different directions. After the great events of the 1790s, the Napoleonic wars, and then the post-1815 retrenchment, the latter saw renewed waves of revolution in 1848 and 1871. The infant US, by contrast, saw only the faux-democracy of the Jacksonian period and then deepening stagnation and paralysis over the slavery issue. Revolution did arrive in 1861-65 when the northern bourgeoisie expropriated the southern planters, America’s own homegrown aristocracy. But it was a curiously truncated affair. “Up to now we have witnessed only the first act of the Civil War – the constitutional waging of war,” Marx wrote. “The second act, the revolutionary waging of war, is at hand” (emphasis in the original).[8] But he was wrong. Once the war was over, the old conservatism reasserted itself as northern industrialists looked to the old southern ruling class as potential ally against an emerging proletariat. So they cut Reconstruction short and restored the old Constitution with just a few minor tweaks. Where France would run through some 15 constitutions from 1789 on, the United States would stick with just one now that the southern plantocracy was back in the saddle as a junior member of the bourgeois dictatorship.

This is the same slaveholders’ document that, centuries later, is such a shambolic mess. Constitutional interpretation, the business of making sense out of a plan of government cobbled together over a four-month period in 1787 and then amended via an arbitrary and chaotic procedure set forth in Article V, is by now a major industry employing thousands of the most brilliant minds in the country, every last one of them convinced that there’s nothing wrong with America that the document can’t fix. But the more they peer into the ancient innards, the more confused they become. The Second Amendment’s meaning, for example, once seemed clear: the right to bear arms connoted nothing more than the right to join “a well-regulated militia” in the form of the US National Guard. Gun control could proceed while modern liberalism was secure. But beginning in the late 1980s, legal analysts – with liberals and leftists leading the way, ironically – took a second look and concluded that the 18th-century text guaranteed an individual right of gun ownership after all. Indeed, one scholar went so far as to argue that the amendment amounted to a kind of mini-constitution in its own right, one enshrining a theory of government in which “ordinary citizens … [would] participate in the process of law enforcement and defense of liberty rather than rely[ing] on professionalized peacekeepers, whether we call them standing armies or police.”[9]

It's a vision of neighborly government very different from the representative government that the rest of the document seems to prescribe. Similarly, Article V had once been seen as “unusually clear and constraining,” a bit of 18th-century legalese that, according to the Supreme Court, “is clear in statement and in meaning, contains no ambiguity, and calls for no resort to rules of construction.” At least one section of the Constitution was thus problem-free. Yet a close reading now shows that the clause is as confusing and contradictory as the rest of the text. No one can satisfactory explain, for instance, why the 27th Amendment is part of the Constitution despite an absurdly prolongated ratification process stretching out across two centuries or why the Equal Rights Amendment is not even though it would eventually win approval from three-fourths of the states despite an arbitrary seven-year deadline that Congress tacked on at the outset.[10] Like Protestants and Catholics arguing over which books belong in the biblical canon, Americans can’t even be sure as to what’s in the Constitution and what’s not.

Yet conservative democracy is incapable of dealing with such problems in a constructive way. All it can do is circle back to first principles – to what that great political theoretician Nancy Pelosi recently called “the beautiful, exquisite, brilliant genius of the Constitution.”[11] The result is rather like a robot repeating the same words over and over again: “checks and balances … separation of powers … founding fathers.” Politicians like Pelosi think repeating such magic phrases will make the problems go away. But it won’t. It merely assures that they will return worse than ever. The more politicians engage in the old rituals of equality – the backslapping, the grinning, the increasingly absurd patriotic rhetoric – the more farcical the whole affair becomes.

The mindless application of old formulas is thus tearing the country apart. But it’s important to get the relationship between the Constitution and larger society straight. Initially, the Constitution served as the legal-political skeleton around which US capitalism grew up. It took the conservative democracy of the colonial period, deepened and extended it, and then entrenched it in terms of the system as a whole. Conservative democracy became the basis for a system of mass production and consumption in which an artificially enlarged middle class would shop, eat, and play while worshipping at the capitalist shrine.

But the more the crisis intensifies, the more impossible “democratic” capitalism becomes. Once Madisonian mechanics, all those levers and pulleys that keep checks and balances in place, seemed to work, which is to say seemed to serve the needs of capital. They kept black people in their place, crushed strikes, and consigned leftwing radicalism to the margins. But as capitalism has declined, the old machinery is declining with it. Gridlock is intensifying, the atmosphere on Capitol Hill grows ever more poisonous, while politics are approaching something resembling civil war. Democrats would like to blame it all on Donald Trump, but Trump is merely a manifestation of a larger structural crisis. The more that capitalism collapses, the more the political structure will collapse with it. The result will either be anarchy, rightwing dictatorship, or a combination of both. But it will mean the end of US democracy as we know it.

The tragedy of the Civil War is that it didn’t head off in the revolutionary direction that Marx expected. To the contrary, while the northern bourgeoisie overthrew the slavocracy, it wound up putting the slaveholders’ constitution back on the throne. Black people, socialists, and democracy in general have paid a terrible price as a consequence. The working class should finish the job a second time around.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- V.I. Lenin, “Letter to American Workers,” Aug. 202,2 1918, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1918/aug/20.htm. ↩

- R.R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2014), 261, 510, 679. ↩

- Ibid., 343 ↩

- Ibid., 40, 753. ↩

- Stacy Schiff, The Revolutionary Samuel Adams (New York: Little, Brown, 2022), 48. ↩

- Palmer, Age of the Democratic Revolution, 174-75. ↩

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, vol. 1 (New York: New American Library, 1972), 284. ↩

- “A Criticism of American Affairs,” Die Presse, Vienna, Aug. 9, 1862. ↩

- Sanford Levinson, “The Embarrassing Second Amendment,” Yale Law Journal 99, no. 3 (December 1989), 650-51. ↩

- David E. Pozen and Thomas P. Schmidt, “The Puzzles and Possibilities of Article V,” Columbia Law Review 121, no. 8 (December 2021). ↩

- https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/11520-0 ↩