As the Supreme Court’s term comes to a close, the results of landmark cases on Affirmative Action and Student Debt Relief have recently been released. On June 29th, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 (in the UNC case) and 6-2 (in the Harvard case), that affirmative action policies violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution and are therefore unlawful.[1] On June 30th, the Supreme Court struck down President Biden’s planned student debt relief 6-3 based on the notion that Biden overstepped his executive authority.[2]

There is no shortage of critique of the Supreme Court, which is perhaps the most anti-democratic institution in the United States federal government.[3] There have also been several effective arguments against the Constitution itself in the pages of Cosmonaut including Comrade Luke Pickrell’s excellent article from June 21st.[4] The Constitution, written as a power-sharing agreement between finance capital, big landowners, and slave drivers, created the Supreme Court and I similarly back Comrade Pickrell’s call for the slogan of our time: “Fight the Constitution, demand a democratic republic.”[5] As our struggle against the Supreme Court and the Constitution continues, it is worth considering what an effective socialist position toward higher education looks like given these anti-democratic assaults by our anti-democratic governing bodies, especially for those of us who work in higher education such as myself.

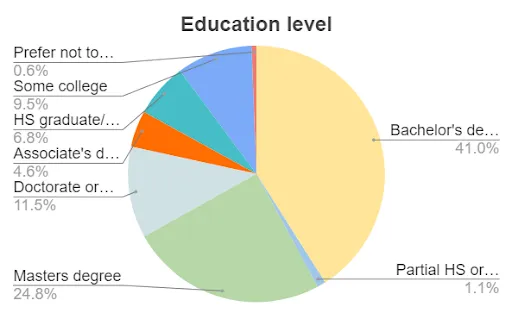

Working through these questions is important for DSA, which has a high density of college-educated members. For example, in 2021, DSA released demographic information to this effect at its national convention:

As seen above, 41% of DSA members had an undergraduate degree, 24.8% had a master’s degree, and 11.5% had a PhD.[6] Demographic shifts have surely occurred in the last two years, but with supermajorities of members having at least a bachelor’s degree, we are clearly a college-educated organization. Much ink has been spilled fretting over levels of higher education in our organization and I will not wade into the argument here. Rather, it is worth considering the institution that many of us have worked through (or continue to work in) and what our relationship to higher education should be as socialists.

It is clear that the material position for higher education is dire. State funding for higher education has only declined over time, while increased federal funding has primarily been distributed through Pell Grants.[7] This has directly resulted in skyrocketing student tuition, larger class sizes, and the adjunctification of instructors. The majority of instructors (75.5%) at colleges and universities are off tenure track and just over 50% are part-time adjuncts who teach a class or two at a time.[8] I am a perfect example of the new normal for higher education. I hold a doctorate and am a writing instructor at the University of Colorado (CU) Boulder. I am off the tenure track, have a three-year contract, teach four classes a semester (eight a year), and am required to do additional committee work to keep my program running. I also make $55,000 a year, which is considered relatively stable for someone off the tenure track. Adjuncts are in an even more perilous position, with some of the worst pay, job security, and benefits. Of course, rather than reinvesting in students, staff, or teachers, public university education has only become further bureaucratized with more provosts, deans, chancellors, etc. For example, a new dean was just hired at CU Boulder for a base salary of $400,000 a year,[9] while an adjunct in the CU Boulder College of Arts and Sciences would need to teach roughly eighty classes a year to make that much money.[10]

Many of us in socialist circles have heard these critiques before. The public university system in the United States is clearly under austerity management as funding dries up and the huge bureaucratic machinery of higher education can only find ways to reconstitute itself, rather than support their stated mission of being a “public good,” educating students, and providing necessary research to better our society. These Supreme Court cases reveal a further sally against higher education by the reactionary right, which seeks to make a case of reverse racism and punish those who take out loans to pay for an unaffordable education.

In actuality, these cases and reactions to these cases obscure the issues of diversity and cost in higher education. As socialists and various radical academics have pointed out,[11] free college education and open admissions, along with robust ethnic studies/student groups[12] would obviously solve the problem of cost and would go a long way in bringing students of color in and retaining them. Arguing over this or that policy or court ruling obscures one of the fundamental issues of higher education: the lack of material investment. We must never lose sight of this overall structural failure of higher education, which will always be elitist and reinforce bourgeois values until we tear down the gates, allow everyone to enter, and calibrate the institution based on these new entrants rather than the other way around.

The other reality that is often obscured in these conversations and by these supposedly “non-political” Supreme Court decisions is the inherently political nature of education and knowledge production. Conservatives and liberals have figured this out to some degree. For example, the Bruce D. Benson Center for the Study of Western Civilization at CU Boulder was founded by Bruce Benson, a former oil and gas executive who served as the CU system president from 2008 to 2019. Benson was the chairman of the Colorado Republican Party from 1987 to 1993 and their nominee for Colorado governor in 1994.[13] The Benson Center is most famous for making John Eastman the "Visiting Scholar for Conservative Thought and Policy" in the 2020-21 academic year. Eastman is a former professor at the Chapman School of Law. He also advised President Trump on legal theories to reverse the results of the 2020 Presidential election.[14]

This was an overt, ridiculous move to shift the university ideologically and The Benson Center was widely criticized for appointing Eastman (he was later asked not to come to campus but was still compensated).[5] However, this also plays out on minute levels when we consider the way liberalism percolates through higher education. For example, the following passage was used as an example of how to employ vivid language in a textbook written by members of my department for a first-year writing class:

When Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi condemned Goldman Sachs for its role in the 2008 financial crisis, he didn’t merely say the company was morally corrupt. He called it “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” It’s hard to forget vivid language like that, and difficult not to react to it viscerally. It is a phrase of tremendous power.But the power of vivid language is also its drawback. It can quickly amplify a claim beyond its available support. In Taibbi’s metaphor, Goldman Sachs is not merely evil: it is a horrifying inhuman parasite without the slightest redeeming quality. Intentionally or not, Taibbi suggests that Goldman Sachs cannot be reformed and must be destroyed. By appearing to demonize the company—and by extension, those who sympathize with it—he risks provoking Goldman’s supporters into a posture of emotional and intellectual defensiveness that makes further persuasion difficult.[15]

In this passage, one can see how liberal, bourgeois values are inculcated into students passively through the textbooks they read. Here a student learns about what vivid language is, but also the primacy of using polite persuasion to try and convince finance capital to not destroy everything in its path.

I bring these examples up to illustrate that the modern university system is as Louis Althusser suggests in “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” Ideological State Apparatuses (or ISAs) are “a certain number of realities which present themselves to the immediate observer in the form of distinct and specialized institutions.”[16] He goes on to describe educational systems as one of many ISAs. Althusser claims that as an ISA, schools “function massively and predominantly by ideology, but they also function secondarily by repression, even if ultimately, but only ultimately, this is very attenuated and concealed, even symbolic.”[17] Unlike Repressive State Apparatuses (or RSAs) such as bourgeois governments, the police, or the military, where repression is explicitly violent or at least coercive, sites of education function primarily through ideological means and only secondarily through repression. Althusser goes on to maintain that schools are the primary ISA: “...the ideological State apparatus which has been installed in the dominant position in mature capitalist social formations as a result of a violent and political ideological class struggle against the old dominant ideological State apparatus, is the educational ideological apparatus.”[18]

Thus, for Althusser, sites of education are one of the primary places of disseminating ideologies that reinforce the control of the ruling class in a capitalist society. Of course, this is obscured by the fact that schools are represented “as a neutral environment purged of ideology...where teachers respectful of the ‘conscience’ and ‘freedom’ of the children who are entrusted to them...open up for them the path to the freedom, morality and responsibility of adults by their own example, by knowledge, literature and their ‘liberating’ virtues.”[19] Schools, especially universities, appear to be non-ideological in their search for knowledge and in how they teach but are in actuality always ideological in their pursuits.

Althusser also tells us that “ISAs are not the realization of ideology in general, nor even the conflict-free realization of the ideology of the ruling class...It is by the installation of the ISAs in which this ideology is realized and realizes itself that it becomes the ruling ideology.”[20] Consequently, ISAs do not spring up from the ground, completely realized when a particular class has begun to rule society. Rather, this is a process realized through “continuous class struggle: first against the former ruling classes and their positions in the old and new ISAs, then against the exploited class.”[21] This process continues to play out in American universities, which do everything they can to appear “non-political” or as a “public good,” but as is apparent in my above examples and in how our elites legislate, initiate culture war, and withhold or dole out funding, this neutrality is impossible. Therefore, as an organization that is primarily made up of college-educated people and as socialists, it is our responsibility to wage class war on this terrain just as we would on a shop floor or in the streets.

Initiating this struggle has many unique challenges and boons that come with the territory. One of the major issues that those of us who work in higher education as tenure-track or tenured professors face is laid out by Karl Kautsky in “The Intellectuals and The Workers,” which is that there is an “antagonism between the intellectuals and the proletariat.”[22] Intellectuals are isolated, live a bourgeois lifestyle, fight through argument rather than through strength in numbers, and most importantly to my point:

conceives himself as very superior to the proletarian. Even Engels writes of the scholarly mystification with which he approached workers in his youth. The intellectual finds it very easy to overlook in the proletarian his equal as a fellow fighter, at whose side in the combat he must take his place. Instead he sees in the proletarian the latter’s low level of intellectual development, which it is the intellectual’s task to raise. He sees in the worker not a comrade but a pupil.[5]

It makes sense that, after years and years of education, deep thought, writing, and all the hoops academics are required to jump through, one becomes convinced of their unique genius, hard work, and ability to understand things others cannot. But this does not benefit our struggle. The ideal intellectual in the proletarian struggle is as Kautsky points out:

an intellectual who thoroughly assimilated the sentiments of a proletarian, and who, although a brilliant writer, quite lost the specific manner of an intellectual, who marched cheerfully with the rank-and-file, who worked in any post assigned to him, who devoted himself wholeheartedly to our great cause, and despised the feeble whinings about the suppression of one’s individuality.[5]

This is the struggle of the bourgeois intellectual, who must suppress their own class character in order to be a successful member of the proletarian movement. Of course, this is only roughly 25% of the instructors in higher education. As I mentioned before, the vast majority of us have these graduate degrees (or are currently in graduate school) and are imbued with the same kind of bourgeois intellectual values but are not given the same job protections or the bourgeois lifestyle of our tenure-track colleagues.[23]

Apart from non-tenure track faculty, there are of course many other job classifications in what scholars of academic history call the “multiversity:” an institution of dispersed bureaucracy and administration, run by white-collar managers, not students and teachers.[24] In the case of public universities, higher-level decision-making is primarily vested with officers who are appointed by a state-wide elected Board of Regents. Oftentimes, there are also student and faculty councils, but these are given advisory power rather than decision-making capability. The administrators with real power are sometimes former teachers and sometimes not, but the result of their employment is to manage and administrate the university, not teach or do the daily maintenance of keeping the university running (like janitors, foodservice workers, and maintenance workers do). These administrators are also often paid the best of all university workers. As I mentioned before, the newly hired dean at CU Boulder makes a base salary of $400,000 a year.

This results in the same kind of careerism and self-interest negotiation one would see in any other white-collar work. A dean making $400,000 a year might have all the best intentions in the world, but he, she or they will not commit to the necessary radical changes that higher education clearly needs if there are cuts to be made or an easier reform move to make. These are people committed to their spreadsheets and maintaining their prestige and class positions.

This is all to say that, whether we like it not, sites of higher education are highly important institutions that serve as a powerful tool for class rule. The liberal humanist education that many of us received as students (and that I continue to provide to students) is of value, critical thinking is of value, hell, setting off on your own for four years while you figure out what to do with yourself is of value. But we must not forget that this is also a place of ideological and sometimes outright class struggle. Socialists knew this in the 1960s and 70s, which is how we achieved the formation of ethnic studies departments[25] and, briefly, open admissions in the CUNY system.[26] As the Supreme Court continues to assault the ability of poor and/or minoritized students to attend public universities and the institution reaches further levels of crisis, it will only become more important for socialists to turn our eyes toward struggle on this terrain.

I do not pretend to have all the answers to waging class war in higher education, but I have sketches of ideas based on what I’ve read and observed. Hopefully, this can serve as a jumping-off point for further development:

- Enact Class Suicide: Any instructor-level faculty should commit “class suicide,” as outlined by the radical theorist Steven Osuna, that challenges the petit bourgeois intellectual and scholar to disinvest from their social positions, produce radical scholarship whose research, arguments, and conclusions have a preferential option for the poor, and be informed by the sounds and visions emerging from the trenches of racial capitalism.[27] This means setting aside publication, tenure, financial security, accolades, etc. and focusing on research, publications, or teaching that benefit the proletarian struggle. For example, I will be teaching a class this fall called “The Writing and Rhetoric of Socialism,” which I am crafting alongside my local YDSA and DSA chapter. This is an opportunity to propagandize other students, who are required to take this general education writing class, but also gives my comrades an opportunity to develop their political education. If I am allowed to continue this work, I can run the class several times, which will further my reach but will also give us critical time to reflect and develop the course.

- Reject Bourgeois Intellectualism: If you’re a radical student, staff member or non-tenure track faculty, don’t follow tenured/tenure-track faculty or administrators in their politics or tactics unless they have demonstrated their commitment to the struggle. For example, are they active members of any socialist organization or labor union? Are they willing to actually listen to what you believe about how the university, department, or class should run? What are their feelings about true democracy?

- Demand Democracy: When propagandizing and making demands, emphasis should be on the anti-democratic nature of the university. Students, faculty, and other higher education workers should run public universities. This cannot happen with an institution run by administrators. Therefore, while we should be consistently working in traditional trade union struggles over pay, job security, etc. to bring unionists into the struggle for socialism, we should also be fighting for the destruction of educational bureaucracy. Faculty, students, and staff should run the university through their faculty, student, and staff councils, not through overpaid administrators.[28]

The struggle for the democratization of higher education in the United States mirrors our fight against the Supreme Court and the Constitution. Let us reject further austerity and bureaucratization in colleges and universities across the country and fight instead for universal, free education that mirrors a diverse student body and a truly democratic system of academic governance.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Lawrence Hurley, “Supreme Court Strikes down College Affirmative Action Programs,” NBCNews.com, June 29, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/supreme-court/supreme-court-strikes-affirmative-action-programs-harvard-unc-rcna66770. ↩

- Jessica Parker and Bernd Debusmann Jr., “US Supreme Court Strikes down Student Loan Forgiveness Plan,” BBC News, June 30, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-65931653. ↩

- Ben Burgis. “The Supreme Court Is an Antidemocratic Monstrosity. We Should Break Its Power.” Jacobin, January 2, 2022. https://jacobin.com/2022/02/judicial-review-democracy-liberals-minorities-breyer-warren-biden. ↩

- Luke Pickrell, “The Slogan of Our Time,” Cosmonaut, June 22, 2023, https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/06/the-slogan-of-our-time/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- DSA Demographic Information, 2021 ↩

- Fiscal Federalism, “Two Decades of Change in Federal and State Higher Education Funding,” October 10, 2019, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2019/10/two-decades-of-change-in-federal-and-state-higher-education-funding/. ↩

- New Faculty Majority, “Facts about Adjuncts,” New Faculty Majority, https://www.newfacultymajority.info/facts-about-adjuncts/#:~:text=Vital%20Statistics,often%20known%20as%20%E2%80%9Cadjunct.%E2%80%9D. ↩

- Annie Mehl, “CU Boulder selects Glen Krutz as new dean of the College of Arts and Sciences,” Daily Camera, June 2, 2022, https://www.dailycamera.com/2022/06/02/cu-boulder-selects-glen-krutz-as-new-dean-of-the-college-of-arts-and-sciences/#:~:text=Krutz%20will%20earn%20a%20base%20salary%20of%20%24400%2C000. ↩

- University of Colorado Boulder, “Compensation,” College of Arts and Sciences Faculty and Staff Site, https://www.colorado.edu/asfacultystaff/personnel/policies-procedures/faculty-temporary-other/recruitment-hiring/compensation. ↩

- James Hoff, “Why We Need Free Public Higher Education Now,” Socialist Alternative, September 27th, 2015, https://www.socialistalternative.org/2015/09/27/free-public-higher-education/. ↩

- San Francisco State University, “Ethnic studies curriculum tied to increased graduation, retention rates, study finds,” Phys.org, https://phys.org/news/2020-12-ethnic-curriculum-tied-retention.html. ↩

- Jim Martin, “CU can do better than Bruce Benson,” The Denver Post, February 6 2008, https://www.denverpost.com/2008/02/06/cu-can-do-better-than-bruce-benson/. ↩

- Elizabeth Hernandez, “CU regents call John Eastman ‘an embarrassment’ as Jan. 6 committee includes ex-professor in criminal referral,” The Denver Post, December 19, 2022, https://www.denverpost.com/2022/12/19/john-eastman-cu-boulder-january-6-committee/. ↩

- University of Colorado Program for Writing and Rhetoric, Knowing Words: A Guide to First-Year Writing and Rhetoric, 2021 – 2021, 17th Ed. Fountainhead Press, 2021. ↩

- Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological Apparatuses (Notes toward an Investigation),” Lenin and Philosophy, and other Essays, Monthly Review Press, 2001, p. 17. ↩

- Ibid. p. 19 ↩

- Ibid. p. 26. ↩

- Ibid. p. 30. ↩

- Ibid. pp. 58-59 ↩

- Ibid. p. 59. ↩

- Karl Kautsky, “The Intellectuals and The Workers,” Marxists.org, https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backiss/vol1/no1/kautsky.html ↩

- Those in the non-tenure track category are the majority of college professors, and they have a unique class character that I do not think has been explored enough given their preeminence in staffing for higher education and the political possibilities their employment offers. This bears further study at some point but is not the major thrust of this article. ↩

- Donna Strickland, The Managerial Unconscious in Rhetoric and Composition, Southern Illinois University Press, 2011. ↩

- Asal Ehsanipour, “Ethnic Studies: Born in the Bay Area from History’s Biggest Student Strike,” KQED.org, July 20 2020, https://www.kqed.org/news/11830384/how-the-longest-student-strike-in-u-s-history-created-ethnic-studies. ↩

- Stephen Brier, “Why the History of CUNY Matters: Using the CUNY Digital History Archive to Teach CUNY’s Past,” Radical Teacher, vol. 108, no. 1, May 2017, pp. 28-35. ↩

- Steven Osuna, “Class Suicide: The Black Radical Tradition, Radical Scholarship, and the Neoliberal Turn,” Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought, Edited by Adolph L Reed and Kenneth W. Warren, Routledge, 2010. P. 28. ↩

- Faculty and Student councils are another unique feature of public higher education that require further analysis. ↩