I remember the first time I heard Fleet Foxes’ “Helplessness Blues” at the end of my second year of high school. The eponymous song on the album has a line that has stuck with me since that first listen:

I was raised up believing I was somehow unique / Like a snowflake distinct among snowflakes, unique in each way you can see / And now after some thinking, I'd say I'd rather be / A functioning cog in some great machinery serving something beyond me

Something about this line rang so true for me: I clearly remember the feeling of warmth that shrouded my 15 year old self. I have come back to this line time and time again over the years, and have never ceased to identify with it wholeheartedly. The desire to serve something greater, to be a cog in the machine, is one of the purest and most consistent threads of my life.

While I could spend months questioning the origins of this desire (perhaps my Catholic upbringing, or an ingrained sense of Midwestern modesty, etc.) the effects have, perhaps, been a bit clearer: I find “grind” culture deeply and inherently distasteful, I can’t imagine forgoing the simple pleasures of life for overtime hours, and organizing with whatever union I’m a part of has always been more important than pursuing “productivity.” Our appreciation of snow does not come from the individual snowflake, but rather the force of billions of snowflakes falling together.

The most prominent example of my internalization of a Fleet Foxes’ lyric, however, is my current job, or what I have chosen to do with my life: I am a bureaucrat. (Does that sound unglamorous? Did you wince at that word?) To put it more neutrally, I have spent most of my adult life working for the New York City government at various levels and agencies. And believe me, I understand the universally negative connotation associated with the public sector, the perceived inefficiency and waste of its bureaucratic mechanisms. I have spent more than a few afternoons close to tears lamenting the snail’s pace with which almost everything gets done, and I have found myself nodding along to critiques of bureaucracy from both the Left and the not-so-Left on more than one occasion. But the more time I devote to city government and the more I grow into my political beliefs as a leftist, the more I realize the inherent necessity of bureaucracy in almost everything I believe in: a vigorous social and welfare state, redistributive politics, jobs and financial security, a robust labor movement, democratic participation…the list could go on. I am finally willing to proudly proclaim that, as leftists, we must not only contend with bureaucracy, but embrace and use it to its fullest potential.

Local Government

Let’s start with what I know, which is my work. I was initially drawn to the public sector by youthful idealism and the promises of millennial socialism: the brief moment of political optimism between Bernie Sanders’ first presidential campaign and Trump’s election in 2016 had just enough influence on me to imprint the idea that, perhaps, our political institutions could be salvaged from the inside.

I quickly learned, however, that while some people join government work for the politics, everyone stays for the stability. As my political optimism waned (and returned, and waned again—it is an endless cycle), I found myself drawn to the routined security of a unionized government job. City workers in New York have some of the most stable employment in the country with a hefty benefits package that includes comprehensive health insurance and the exceptionally elusive “pension.” This stability is as attractive to a newly minted college graduate as it is to a middle-aged mother of three, and because of this I often feel that my current office is a microcosm of New York City: racially, economically, and educationally diverse.

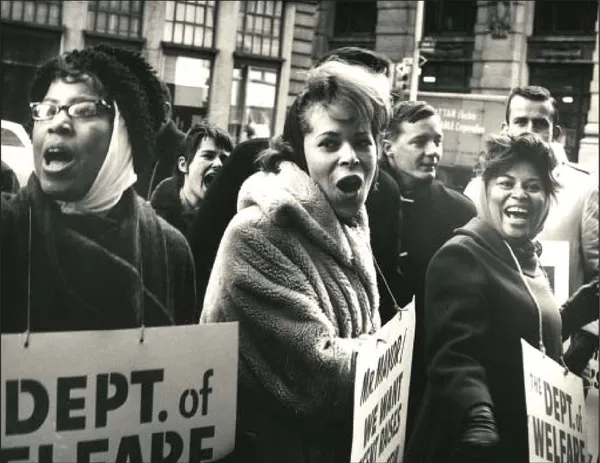

As it turns out, this isn’t just a coincidence. The public sector union movement reached its height amongst New York City workers in the tumultuous decade of the 60s and was largely spearheaded by scrappy upstarts in the city’s Welfare Department. Dissidents in the rank-and-file of District Council 37 (DC 37, the largest NYC employee union), unhappy with abysmally low salaries, miserable working conditions, understaffed offices, and being subject to the whims of whichever mayor was in power, broke off to form the Social Service Employees Union (SSEU). The SSEU took a harder left stance than DC 37, engaging in street protests, organizing brief wildcat strikes, internally implementing more democratic structures, and connecting their union movement to the larger revolutionary struggles happening at the time. Their sustained and radical actions throughout the 1960s led to higher wages, better union security measures, and institutionalized collective bargaining rights, before they were reabsorbed into DC 37 in 1969. These labor struggles ensured that the public sector and civil service, not only in New York but in many places around the country, are dignified and often fairly lucrative career paths for people of all backgrounds. Indeed, the civil service in New York is one of the last vestiges of upward mobility for the working classes in the city.

My first argument for bureaucracy, then, is simply that it provides gainful and sometimes meaningful employment to large swaths of people. And because our most pronounced and intricate bureaucracies occur largely in the public sector, these bureaucratic jobs are often unionized with better benefits than the private sector.

Besides, we are all cogs for something greater, and as far as I can tell, there are worse machines than the local government of New York City. These bureaucratic jobs not only offer benefits to those working within the system, they also play a critical role in delivering services to those outside of it. It makes sense, then, that the most radical components of the public sector union movement in New York were spearheaded by employees working directly in social services: these employees had firsthand knowledge of the issues facing their clients, New York’s working poor. Even after decades of austerity politics, the city’s social state is quite robust when compared to other municipalities or states with lower tax rates. New Yorkers have the most comprehensive public housing system in the country, access to state-mandated paid maternity leave, affordable housing lotteries at a variety of income levels, a public hospital system, low-cost insurance plans, and a large, prestigious public research institution (the City University of New York, or CUNY) that is comparatively cheap.

The oft-maligned bureaucrats ensure the day-to-day functioning of these social programs. Even if they don’t fully believe in what they’re doing or connect their work to a larger political ecosystem, NYC’s bureaucrats are acting in service of a common goal: maintaining the daily liveability of the city for all of us, especially the city’s most vulnerable who constitute the vast majority of recipients of city services. Ideally, a bureaucratic system works to maintain this drive towards welfare and redistribution through the small processes the bureaucrats act out every day, day by day. This “slow march towards progress” mindset, which I see even in my most jaded co-workers, feels like an inherent contradiction to the achingly neo-liberal refrain of “what is best for profit margins, most efficiently.” I think of a friend who works 60 hour weeks as a corporate lawyer, wearily joking over drinks that he spent his day “maximizing shareholder value.” He is miserable (with an increasingly gray head of hair) because he is expected to work ungodly hours and claw his way to the top of the heap for goals no one even pretends to believe are good for the world. (He is currently applying to Legal-Aid jobs). In our age of hellish privatization and cut-throat competition, there is something radical about people coming to work every day in service of something other than making someone rich.

The bureaucracy in New York, however, is not without its problems, and barrages of bureaucratic critiques are far from unreasonable. While tens of thousands of New Yorkers sleep on the streets every night, it takes on average 371 days to fill affordable housing units through the affordable housing lottery. Obtaining any sort of government subsidy requires mountains of paperwork, multiple office visits, and thousands of dollars in lost time. City bureaucracy is a hindrance to justice almost as often as it helps facilitate it, and countless New Yorkers are caught in its vicious cycle every day.

The public sector union struggles of the 1960s also show us that bureaucracy is a double-edged sword. As they so often are, the hard-fought gains won by the SSEU were compromised with measures that restricted the scope of collective bargaining and institutionalized union leadership to be more in line with local politicians. Incorporating themselves into the city bureaucracy dissolved the union’s most radical claims.

Zooming Out

So what can the local government in New York tell us about our larger negotiations with bureaucracy on the Left? Max Weber, one of the pre-eminent theorists on social structures in the 20th century, laid out six rules for a functioning bureaucracy: authority and hierarchy, formal rules and regulations, division of labor (specializations), impersonality, career orientation, and formal selection process. These principles, at least in my experience, ring largely true in New York City government (though I doubt Weber would hold us up as the pinnacle of efficiency). There are clear hierarchies and chains of command, all employees are trained on the same standardized rules of conduct, and career paths and selection processes are well defined through the civil service system.

Weber, in classic bureaucratic fashion, holds a fairly neutral view on the moral or political implications of bureaucracy itself and emphasizes its use as a tool to structure organizations. I would argue, however, that there is an inherently leftist orientation to some of Weber’s requirements. A “division of labor” implies a dependence on others in your organization to manage tasks and complete projects; camaraderie develops when people are forced to rely on one another. Division of labor, formal rules and regulations regarding workplace conduct, and clear-cut time/leave policies institutionalize healthy work/life balances as the norm. No one is expected to do more than they are required, because these boundaries are already incorporated into the structures of the machine itself—a machine does not run “better” if one gear goes into overdrive.

When thinking about the division of labor enabled by a bureaucratic system, I am often reminded of Marx’s sarcastic rant against 19th century work culture:

The less you eat, drink and buy books; the less you go to the theatre, the dance hall, the public house; the less you think, love, theorise, sing, paint, fence, etc., the more you save—the greater becomes your treasure which neither moths nor rust will devour—your capital. The less you are, the less you express your own life, the more you have, i.e., the greater is your alienated life, the greater is the store of your estranged being.

The more we work and the more we try to define ourselves by our individual productivity, the less human we become. A clean break between life and work was (and still is) a hallmark of the labor movement, and leisure time is a necessary component of the liberation of the working class. We divide labor simply to make things easier, to give us more time in the day to pursue the vast array of other activities that constitute our shared humanity. This component of bureaucracy often feels like a pushback to a late capitalist culture that seeks to commodify the whole self. An Instagram influencer can never be fully off the clock when their career consists of publicizing their own life for mass consumption; a tech founder must turn all personal connections into potential networking contacts to accumulate start-up capital. Bureaucracy resists this commodification of personhood by enforcing the divide between work life and lived life, and by maintaining a division of labor that does not incentivize people to do work that is not required of them. It is no accident then that some of our greatest artists and writers have at one time or another been civil servants: Verlaine kept a day-job at the Mayor of Paris’ office, T.S. Eliot served as a bank clerk for almost a decade, and Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko both got their start as public artists employed by the Works Progress Administration.

I would also push against the notion that bureaucracy is inherently “impersonal.” The alleged impersonality is tied up in a neoliberal resistance to “one size fits all” standardizations that serve to level the playing field for career advancements. Ironically, in a Forbes Magazine critique of bureaucracy, author Penny Abeywhardena argues for an institutional re-focus on “trust” and “informal tools and soft-power” in the workplace to combat the dehumanizing effects of the office environment. But playing part in a bureaucracy facilitates the daily, years-long types of interactions that foster trust and community. In my experience, the daily difficulties of life in the public sector and navigating the bureaucratic machine lead to bonds forged in fire, to teams of odd couples united in their dispassionate commitment to the job of slow and steady civic improvement.

Things get a bit more complicated when we attempt a more dynamic class analysis of bureaucracy and the bureaucrat’s role in society. Bureaucracy takes on its most oppressive form when it becomes a class unto itself, rather than a system through which to advance the interests of the working class. This notion of a “Bonapartist” state or an “empire without an emperor” derives its namesake from post-revolutionary France, and describes a system with no loyalties other than to the system itself. This creates bureaucracy for the sake of bureaucracy, enabling endless rules with no higher meaning other than to serve a centralized power. Even well-intentioned leftist movements tend to fall into this trap; indeed, once in power, the Bolsheviks quickly appointed an elitist class of bureaucrats, detached from the real needs of the Russian proletariat, in service of a “vanguard governing party.”

In New York City, a “bonapartist” counterpoint to the SSEU’s successful struggles in the 1960s is the United Federation of Teachers 1968 strike, which was sparked by the union’s opposition to largely Black and Puerto Rican-led community control movements in Brownsville and Ocean Hill. UFT’s largely white and Jewish leadership, as well as the rank-and-file, practiced a form of strong-arm unionism that advocated for the advancement of their teachers over all other socio-political considerations. The UFT vehemently opposed the Black Power and public school community control movements that sought to give more institutional power to the Black and Puerto Rican parents and students whom UFT teachers were theoretically supposed to be serving. The UFT’s conservative self-interest, rather than advocacy for the larger ideological struggles of the Left, set back relations between public school teachers and Black and Brown communities in New York City for decades. The lesson here is not that bureaucrats are fundamentally opposed to broader social movements on the Left, but that their politics are constantly contested, and democratic mechanisms inside and outside the bureaucracy must be put in place to ensure their subordination to broader leftist causes.

And then there is the ever-present specter of the ultimate dehumanization enabled by bureaucracy: genocide. One often hears the “Nazi” argument of bureaucracy, or that mindless hierarchy and adherence to archaic rules can lead even the most well-intentioned people to fascism. This can be true, and the Third Reich was nothing if not a bureaucratic death machine. The alienation produced by certain forms of advanced bureaucracy can lead to a violent disregard for human life.

It is worth noting, however, that this critique often comes from the Right itself, most notably in the writings of the Austrian School economist Ludwig Von Mises. Von Mises structures the arguments in his 1944 work Bureaucracy around assumptions that advanced welfare states inevitably descend into Fascism. Aside from being blatantly untrue, the argument reads as some sort of guilt ridden course reversal; the Right washing its hands of the horrors that were then sweeping Europe.

Bureaucracy did not in and of itself create the Holocaust, or any of the other mass horrors of the 20th Century. For every example of genocide, there is a counter-example of bureaucracy facilitating general welfare and redistribution. The Social Security Administration facilitates large transfers of wealth to serve the most vulnerable of American society, including the elderly and the unemployed. The Freedmen’s Bureau was a federal agency established after the Civil War to assist newly freed slaves with finding education, employment, and housing. Project Cybersyn was a technological bureau established by the Socialist Allende government in Chile to monitor and improve state run businesses to promote “worker run” and cooperative enterprises.

Bureaucracy is necessary to the functioning of any large-scale organization, and to organizing society writ large. The political leanings of that large-scale system or society will still depend on the whims of its leaders, its democratic mechanisms, and the willingness of the rank-and-file to agitate and organize within those systems. Guy Patrick Cunningham, in a review in the Los Angeles Review of Books, puts it succinctly:

Bureaucracy, like almost all human inventions, is a tool, and it reflects political priorities. It will never, on its own, be able to counteract power imbalances, because those imbalances will influence the laws that set the perimeters bureaucracy acts within, the priorities executives set for regulators, and the market signals that regulators look to for information. But it is not the source of those imbalances, and any critique of bureaucracy worth keeping needs to acknowledge this.

We must be careful, then, to gear our critiques of bureaucracy toward what we want to accomplish as leftists. The UFT of the 1960s was not inherently anti-revolutionary, and indeed could have been a substantial force for liberatory politics in New York had it recognized its own bureaucratic machinery as something other than a material feedback loop to reinforce the privileges of its membership. A well-functioning German bureaucracy in the 1930s could have been utilized to increase the reach of the welfare state (much as it has been in the post-war era), implement more democratic reforms to its federal model, or quite literally anything other than the systematic annihilation of Europe’s Jewish population. The problem in both these cases was not the presence of bureaucracy; rather, it was the political reality and the democratic mechanisms within the bureaucracies and the broader society that played decisive roles.

Why the Left Should Embrace Bureaucracy

The greatest asset of bureaucratic systems is their use as a tool to implement and maintain the aims of the Left: redistribution, welfare, worker’s rights, and political participation. As diluted as they may become, these political leanings form the basis for much of our bureaucratic state, especially at the local level. The day-to-day pencil pushing of my job does not feel inherently radical, yet much of it contains traces of the social movements that have formed New York City as we know it: the aforementioned SSEU struggles, the early 20th century Progressive Movement which advanced labor regulations, Depression era radicalism and its ensuing public works programs and welfare apparatuses, the struggles for affordable and public housing, and the Civil Rights Movement, just to name a few.

The conflicts of erstwhile idealism within New York City bureaucracy highlight an essential tension between revolutionary impulses and their subsequent institutionalization. Incorporation of a movement or idea into the bureaucracy automatically implies an advanced degree of institutionalization, and some of the original radical elements are bound to be lost. Bureaucracy thrives on a reform, not a revolutionary, mindset. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing – an organized bureaucracy is still the only way to implement a revolutionary project. Rather than thinking of bureaucracy as a hindrance, one can think of it as the revolutionary impulse, codified into posterity for the easiest consumption by the masses.

My instinct then, is not to criticize the bureaucracy itself, but rather which ideas, programs, and politics are sent through the bureaucratic ringer to reach the non-revolutionary masses: a public health system is good, a military police state is bad. As leftists, I believe it is important we make this distinction between the cogs and the machine. A steel beam used to build a railroad track is the same as a steel beam used to reinforce a prison cell. The moral weight of our cogs depends on the machine they help to run.

We can advocate for bureaucratic reforms without falling into the trap that plagues the Right: advocating for the dismantling of bureaucracy all together. Aside from being impossible in a society as advanced as ours, the rhetoric leads to very real material harm in the form of economic deregulation, privatization of capital, and a general disdain for labor rights. Criticizing bureaucracy itself, especially in the public sector, often obfuscates the way bureaucracy is used to serve brutal ends. Talk to anyone who works in consulting, finance, or marketing, and it becomes clear that the tragic triumph of neoliberalism was not dismantling inefficient government bureaucracies, but rather shifting them to an inflated private sector.

If bureaucracy is essential to our goals as leftists, then we must recognize it as a key site of struggle in implementing a socialist project. We must take seriously the genealogies and formational intentions of the systems that govern our lives. We must search for and refine the traces of radicalism that created these bureaucracies, and we must encourage small daily movements towards progress, justice, and redistribution amongst even our most jaded allies.

I still hum a Fleet Foxes tune to myself quite often, as a reminder to keep going on my more frustrating days. I still look for the spark of revolution in the eyes of my coworkers, the mutual acknowledgment of the work to which we have committed ourselves. I don’t always see it. And on those days, I am grateful for a system that encourages us to keep moving towards our goals.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.