As counterintuitive as it might seem, materialism is an idea. More than that, it is an idea about ideas. At its most basic level, we can take materialism to be the idea that some ideas refer to things that are more real than other ideas, and that this level of realness is determined by whether the idea represents specifically material phenomenon. As simple as this statement may seem, it opens up a whole can of worms within philosophy, science, and Marxism specifically. To the extent Marxism has its own philosophy, materialism would be its crown jewel, its treasured and most central achievement. The rejection of idealism by Marx, most emphatically in The German Ideology, and as a positive intellectual praxis in Capital, was in many ways the birth of the social sciences as an objective science. This is not, however, a Marxological regurgitation of what Marx felt about materialism. Materialism, if it is to be tied to an ongoing scientific project, must also be articulated through the most scientific and precise language. Louis Althusser, who operated in the Marxist tradition, was the philosopher of materialism vs idealism par excellence. Althusser’s formulations can be expanded upon through the mature field of semiotics as well as in cutting edge research on cognition and consciousness.

To fully answer this question about the nature of materialism, we can bring it down into the following sub-questions:

- What is an idea?

- What is idealism?

- What are structures?

- How real are ideas and structures?

- What is an ideology?

- Is materialism a dualism or a monism?

- What use is materialist philosophy?

What is an idea? (Why mind reading is possible)

From the perspective of semiotics, an idea is a type of sign, although this is not an uncontroversial truth within the field.[1] A sign is simply something that stands in for something else. Traditionally, we can speak of words, spoken and written, as signs that stand in for some meaning. The word “airplane” can stand in for the image of the plane, or the feeling of traveling inside one, some sense of high precision engineering, and so on. Non-linguistic signs exist too; when the first human ancestor killed another of their kind with a rock, the rock could be turned into a sign itself, in this case for violence. For ideas to be signs, they must refer to something, and stand in for something else. This becomes more complicated, as what words and images stand for are not the actual physical and material things we associate with them, but knowledge of those things and ideas. Therefore, if ideas are to stand in for something, the process of signification of which they are a part of must be inside the mind.

The mind, until very recently, was an impenetrable black hole. This is no longer so much the case. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and brain imaging have made possible a type of “mind reading” whereby scans of a subject’s brain are fed into an AI software program that spits out an approximate image of what the subject is seeing. Importantly, these models can work not just by picking up shapes and colors, but by identifying, semantically, what type of object the subject is looking at.[2] What is astounding about these experiments is that they have worked at all.

The most intriguing of these experiments didn’t even take the usual approach of training a model from scratch with pairs of brain scans and annotated images the subject was looking at. Instead, the experiment extrapolated these pairs of brain scans and annotated images onto an existing text-to-image model, stable diffusion. If one looks carefully at their results, it becomes clear that the strength in terms of semantic fidelity came from this extrapolation to the latent representation of text within the stable diffusion model.[3] This means that within the subjects, the image evoked something that could be pinpointed into the latent space of text, the connections, correlations, and anti-correlations of words and phrases, which mediated the recreation of the images.

These types of experiments are strong evidence that thoughts and ideas are signs that stand in for a more fundamental phenomenal experience or patterns of phenomenal experience, and, crucially, that these signs within the mind are reflections of the signs in material culture in terms of how they are organized. This shouldn’t surprise us. After all, material structures that create phenomenal experiences aren’t that different from person to person. We should expect that similar experiences, including material culture, should produce similar effects within the mind, including on a physical biological level.

An idea, in sum, is a series of connections and organized relationships between phenomenal experience and patterns of phenomenal experience, both of which are codes that exist within material substrates and are produced by material processes.

However, there are challenges to this understanding. What I have just described, these experiments that came from a scientific paper, this specific expression of semiotics; all these things are ideas and knowledge. This is something of the sticky situation that us humans find ourselves in: what I have presented here is an object of knowledge, not the real object itself. We began with ideas and we ended with ideas. We immediately face problems, such as the question of how we can say some ideas are more real than others, as well as the problem of materialist monism (how can we say everything is material if all we have presented thus far are ideas?).

What is idealism?

For some, materialism includes a set of apologetics about the immaterial due to the problems of material monism.[4] In this understanding, we must return to a kind of dualism where the immaterial, the realm of ideas, has its own autonomy. But it is important to clarify that the division of materialism and idealism, as well as the division of the real object and the object of knowledge, are not a dualism of substance, but different things of the same substance. To understand this, it is useful to begin with some formulations of Althusser that greatly elucidate this controversy:

Spinoza warned us that the object of knowledge or essence was in itself absolutely distinct and different from the real object, for, to repeat his famous aphorism, the two objects must not be confused: the idea of the circle, which is the object of knowledge must not be confused with the circle, which is the real objectMarx goes even further and shows that this distinction involves not only these two objects, but also their peculiar production processes. While the production process of a given real object, a given real-concrete totality (e.g., a given historical nation) takes place entirely in the real and is carried out according to the real order of real genesis (the order of succession of the moments of historical genesis), the production process of the object of knowledge takes place entirely in knowledge and is carried out according to a different order, in which the thought categories which ‘reproduce’ the real categories do not occupy the same place as they do in the order of real historical genesis, but quite different places assigned them by their function in the production process of the object of knowledge.[5]

To give an example of this difference in the processes of producing a real object and the object of knowledge, we can consider the difference between the forces which shape the economic history of a nation, and the forces which shape the academic discipline of economic history. While these forces are distinct in space and time, they are all types of labor, and types of natural, material phenomena. Critics such as E.P. Thompson have suggested that this observation is a banal truism[6], but his misplaced criticisms of Althusser reveal precisely the way that it is not. Their controversy over empiricism and historicism reveals precisely the mistake in operation here. For example, Thompson, in multiple parts of his critique, attacks Althusser for not allowing a flexibility of historical concepts, in particular the category of “the working class.” This category, according to Thompson, can only be understood as it appears to evolve over time empirically. As he says “class is defined by men as they live their own history, and, in the end, this is its only definition” and the understanding of class within political economy was nothing more than an imposition by the bourgeoisie onto the working class.[7] Empiricism, as Althusser points out, tries to reduce the object of knowledge to the real object. It is idealistic in this reduction not because it does violence to the real object, but because it does violence to the object of knowledge.

As Umberto Eco says “if something cannot be used to tell a lie, conversely it cannot be used to tell the truth: it cannot in fact be used ‘to tell’ at all.”[8] What is meant by this is that for a statement to be meaningful, it must be capable of failing in a certain way, a given utterance must have a meaning distinct from others such that it can be compared against them. The problem of simply saying class is just “whatever it is experienced as” is that it is much more of a truism than what was advanced before. How could it be wrong? It does not stick its neck out like the political-economic category of class does.

The reduction of our knowledge of reality to our experience of reality also flattens reality itself. If we were to say chemical elements or biological species changed with our broader cultural understanding of them, that would be patently absurd, but for some reason, this is taken to be satisfactory of social concepts. This hints at the fundamental distinction between materialism and idealism: if materialism is a set of claims about ideas, idealism is a set of claims about reality. Specifically, idealism claims that reality is determined, structured, or otherwise subordinated to the mind or the spirit. German Idealism attempted to understand the real world through knowledge of the structure of the subject, or in its “more materialist” conceptions, through the movement of some spirit lurking behind objective reality. Empiricism claims that the only real thing is phenomenal experience which cannot conform to rigid, objective structures. Materialism, in contrast, is a set of claims about the object of knowledge, that one must begin by making meaningful statements about material reality and learn from their success or failure given additional experience to attempt to recreate the objectivity of the real object in the object of knowledge. This is precisely why Marx’s theoretical praxis of materialism begins by laying out an extensive system in Capital.

But this is not the only materialist claim about the object of knowledge or even the first. Related to this claim about the necessity of certain ways of thinking to learn about the material world in its objectivity, which is nothing less than the epistemology of science, is the primacy of the material over the ideal. This is how Marx set out onto materialism; rejecting the idea from Feuerbach that the essence of man was in some way determinative of social reality, but rather, the mode of production had this determining role. This is exactly what is meant by some ideas being more real than others. The categories of political economy, by referring to the way labor is organized, to physical activity in physical space, (even if abstracted to overriding patterns of such activity), were more real than the category of the essence of man. And this greater realness, it is claimed by materialism, means they will necessarily have greater determining power over our reality.

What are structures?

Structures are theoretical objects that are created by their relations to other things. In semiotics, the most elementary structure is the sememe which represents the web of semantic meaning associated with a particular sign. Structures both big and small get their theoretical content from what they are similar and dissimilar to. This relational nature of meaning is one reason why large language models (LLMs) are able to produce meaningful outputs.[9] They are, after all, essentially only using neural networks to map out the relationships between words. This relationality means that structures are medium-neutral. We can speak of a structure of political organization just as easily as a structure of color.

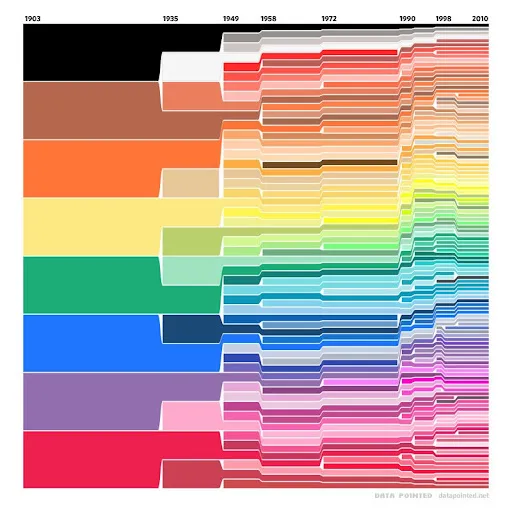

Color is actually quite illustrative, as we necessarily create structures out of the differentiation of colors when we decide to make implements out of them. See how the different kinds of colors divide and multiply as the number of crayons in a pack increase.[10]

The structure emerges as a sort of divvying up of an existing continuum of experience, in this case, the latent space of color. In the real world, or even in virtual spaces that have yet to be fully navigated, there exists a huge multitude of what can be observed. Focusing attention on some part of it is the first step of sign production[11], and therefore the elementary activity of producing larger structures. However, this is still only the first step, the second step is placing this captured piece of continuum into a relationship with other similar pieces. In the case of colors, meaning is attained when they are contrasted and complemented with one another. This is why artists regularly consult a color wheel and experiment with different colors to see how they relate to each other on a canvas. In these cases, the emergence of the color wheel, and the color schismogenesis chart from the constituent signs of individual colors, are also structures of higher levels of abstraction.

What is notable about this is that the structure of color isn’t known from the outset of human culture or the outset of an individual's experience. Rather, it is discovered. Of course, the fact that our color wheel is a wheel (specifically a representation with three axes) is only due to the fact that our eyes normally detect three primary colors (for those whose eyes can only detect two or one colors, this level of differentiation is not possible). But for each level of color dimensionality, there is an associated structure we can propose, we can even propose color representations and projections for parts of the color spectrum we can’t observe with our eyes. No matter what your personal experience is, if you attempt to express yourself through color, you begin to create a structure within your own knowledge to guide you, even if it is more ad hoc than the textbook version.

While we have so far discussed structures that are designed to directly map onto material phenomena, the French structuralists did not begin as materialists.[12] As they became self-conscious of the idea of structure, their first instinct was to use these configurations of cultural knowledge to explain society. They were not concerned with how these structures emerged or were destroyed, or whether there was a hierarchy of realism within structures. This led to idealist beliefs about how myths and archetypes were the true determining structures of society and operating with absolute autonomy. However, there is a way in which this idealism of classical structuralism is self-defeating, which relates to how post-structuralism took over its academic niche.

The “rupture” of structuralism into post-structuralism was less of a rupture and more of a doubling down on its idealist tendencies. This began with Derrida’s well-known essay Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences, which identified many of these obvious idealist problems of structuralism at the time: the fact that the elevation of myth and archetypes in this manner could only stand as a myth in itself and that its claims of “decentering” chauvinist Eurocentrism only created a new chauvinist center. The trouble begins when Derrida refuses to provide a better alternative or to try and advance structuralist linguistics, anthropology, etc. in some scientific way. Derrida seeks to, among other things, displace metaphysics and truth, which are only another type of chauvinistic center imposed onto heterogeneous cultures and modes of thinking. Of course, if Derrida were to elevate these outsides to the current center, he’d be doing the same thing as before and therefore reject such an operation as well. So in the end, the project terminates in a perpetual equivocation about categories, a semiotic parlor trick that reveals how the lesser, diminished category is actually necessary to construct the other. Since these categories are taken as given by Derrida, and he does not dare to create his own system of categories or structures, we are left, quite literally, with nothing.[13]

The discursive, post-structural or post-modern turn as it’s sometimes called, was a similar effacement to collective human knowledge as the marginalist and psychological turn in economics, and even more idealist. It was a stripping of the copper wires from the institution of the humanities, selling it for scrap. The late Althusser responded to it in a way that was constructive, taking the criticisms of post-structuralism and making materialist structuralism more robust in the works that were recently compiled and published under the name Philosophy of the Encounter. The scandal of Althusser murdering his wife in a fit of insanity, and his subsequent life in and out of mental hospitals, meant much of this work was not published or academically received until many years later. However, there were many other structuralists, or people operating in related frameworks, who were also dealing with the post-structuralist critiques. Umberto Eco’s Theory of Semiotics was one example of this, as was The Poetics of Primitive Accumulation by Richard Halpern. These perspectives were marginalized in the humanities and social sciences. It is worth noting that the structuralism of post-post-structuralism was much more materialist, and necessarily so, than the original structuralists. There was a dialectical development in this field of knowledge. Unfortunately, the primary historical memory that exists of structuralism is the triumphant pillaging of it by post-structuralism.

How real are ideas and structures?

Marxist materialism is also a realism, and this is where it crucially departs from certain tendencies which are often quite popular in the mainstream philosophy of science. To paraphrase some of Lenin’s formulations in his critique of Kantianism and neo-Kantianism, we can know things-in-themselves for the simple reason that all knowledge comes from our interactions with real objects. There is no knowledge that doesn’t come from real objects, even our most private internal thoughts are, as was discussed earlier, real objects organized in a particular way to be representational. This is evident when we look at objects such as books, and the somewhat unexpected intelligibility of large language models: the words on a page are always real material objects, and, even without human consciousness to interpret them actively, these words have (at least some) meanings through their relationships to other words in the text, hence why an LLM can spit out sensible text only based off an analysis of these relationships. More recently, multi-model AI models are showing how the meaning of other, non-linguistic phenomena such as sights and sounds, can be connected to these linguistic symbols. Of course, human thought is still more complex than machine thought in ways we don’t totally understand through science, but we should expect that the mind works precisely in this way, like a very chemically complicated bit of clay which is marked by objects that it collides with, and, through its sublime architecture, can organize those marks into what we call knowledge.

Of course, as a matter of acknowledging all possibilities, we can imagine a situation where the structure of our mind as a real object, or the structure of our environment, is shaped in just such a way that it scrambles and prohibits factually correct knowledge of the world around us. If there is any article of faith within materialism it is this wager, that our phenomenal experience is generally accurate enough for us to use our interactions with real objects as a means to create, in principle, accurate knowledge of our world. If this wager were to fall against the side of materialism, it would be a fatal blow to the entire enterprise of modern science, as well as any practical form of knowledge.

In Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-criticism, we see, however, a direct confrontation between Marxist materialism and those who claim to represent the philosophy of the natural sciences. These “empirio-ciritcs” were a tendency of positivism, which does indeed hold an important place in the history of the philosophy of science, and Lenin’s critics have often suggested that his attacks of idealism, even solipsism, against these opponents are too extreme to be accurate, and that Lenin’s formulations represent a crude version of materialism.[14] Contra these retrospectives, the context of particularly Russian positivism totally warrants Lenin’s remarks: Russian positivism as a tendency was much more openly sympathetic to classical idealism and typically conflated epistemology with psychology.[15] A small microcosm of this reality relates to Lenin’s attacks on one L. M. Lopatin, a reactionary Russian academic who edited a journal called Voprosy Filosofii i Psikhologii (Problems of Philosophy and Psychology). As Lenin says in response to the Russian Marxist positivists:

Take the philosophers who base themselves on this school of the new physics, who try to give it an epistemological basis and to develop it, and you will again find the German immanentists, the disciples of Mach, the French neo-criticists and idealists, the English spiritualists, the Russian Lopatin and, in addition, the one and only empirio-monist, A. Bogdanov.”[16]These silly “theoretical” devices (“energetics”, “elements”, “introjections”, etc.) in which you so naïvely believe are confined to a narrow and tiny school, while the ideological and social tendency of these devices is immediately seized upon by the Wards, the neo-criticists, the immanentists, the Lopatins and the pragmatists, and serves their purposes.[17]

This naming of Lopatin is not coincidental. Bogdanov and other Machists had previously written for the very journal Lopatin had edited. The same Lopatin who had nothing but praise for positivism, but also whose impeccable idealist credentials we can easily gleam from the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Lopatin, too, emphasized the agency of the spiritual entities that comprise reality, attributing to them the ‘creative causality’ from which all spatiotemporal causality is derived.”[18]

But, then, if Lenin’s critique was premised on a particularly idealist and psychologistic positivism in Russia, and Marxist materialism is concerned with a scientific project, what is its relationship to the mainstream of positivism? Positivism, as a whole movement, is a diverse project, and there are doubtless some thinkers within it who are materialists in a fundamental way, including some with Marxist sympathies. However, positivism’s influence on the social sciences has typically been used as a weapon against Marxism, and in doing so, has embodied similarly idealist tendencies to the Russian positivists Lenin polemicized against. To understand why this is the case, it’s important to consider that the theoretical thrust of positivism is the primacy of empirical experience against all else. This experience is the only “real” for the positivists, and a theory, for many of them, is only a useful fiction that can be used to explain it. This subordination of theory to empirical observation is useful in some respects in the natural sciences, particularly when approaching the most fundamental physical phenomena such as through the theories of general relativity and quantum physics. Here, the fact that empirical phenomena might differ from theory might point towards greater, more general, theories. At the bleeding edge of our understanding of causality, where there can be nothing to subordinate theory except observation, there exists no other recourse than this test of theory via observation.

Where the trouble begins is when this approach begins to be generalized to sciences that are not quite so privileged. The positivist emphasis on empirical, phenomenal experience can be interpreted in such a way that a sufficiently accurate, simple explanation for a phenomenon is just as valid as any other equally accurate and simple explanation, regardless of what the phenomenon is. For example: that a theory of economic growth leading to lower human birth rates is equally as valid (also equally real or unreal) as the astronomical theory of how a star’s chemical composition relates to its age.

On the face of it, one might not recognize the great peril introduced by this maneuver. It suddenly becomes extremely clear when two theories have objects that are possibly causally connected. Are economic theories equally as real as theories of planetary climate? This is of extreme political and practical concern today. Economic models that are based on laws drawn from observations of human behavior largely diminish the impact of climate on the economy, whereas climatologists have pointed out that only a few changes in degrees can mean the difference between radically different ways of life for mankind, or any human life at all, based off what we know of human biology.

The most consequential proponents of positivism in the social sciences were advocates against any sort of hierarchy of realism in theories. Milton Friedman, the reactionary US economist par excellence, wrote some extremely illustrative essays where he totally rejects the idea that “realism” should matter at all in theory. In particular, he gives the example of a theory for the distribution of leaves on a tree which describes the position of leaves as seeking to maximize the sunlight available to them, analogous to the theory of profit maximization setting prices in economics. Obviously, he claims, leaves do not have any active intelligence that is acting out these equations, but so long as empirical evidence fits, this parsimonious theory is perfectly valid. He compares this theory to one that explains that more leaves can grow in areas that are more exposed to light, which is only superior to the extent it is “more general.”[19] But Friedman’s hand-waving about the generality is where the magic is happening. In fact, without knowledge about other systems in the world and their “realism” it is impossible to tell which theory is in some way more general or more restricted. The second theory, in fact, is superior only due to its realism, due its reference to what we know about trees and light as chemical and physical processes. Simply put, the second theory is superior because it is placed into the hierarchy of realism, at the top of which rests the most basic natural sciences.

Friedman’s project was transparently anti-communist, but more than that, he wanted to kick all vestiges of materialism from the social sciences, and in doing so, he was continuing a long tradition in economics, which includes important names such as Keynes and Marshall. Such materialist realism threatened the bourgeois ideology they produced and elevated to the level of a science. If the “science” of bourgeois economics could be subordinated to trifling things such as climatology, social reproduction theory, or any materialist account of labor, then it would jeopardize its political project which was up until 1980 the preservation of capitalist social relations, and afterward, the preservation of capitalist class itself and its income above all else.[20] The secular state could not both base its legitimacy off of scientific rationality, as was increasingly the case after 1890, and give credence to this hierarchy of realism, for there is no convincing non-parsimonious justification for capitalist income and policies that force people to sell their labor to survive. While Althusser perhaps overstated his case that only the proletariat could create a materialist philosophy and the science of history, the inverse is undeniable: the bourgeoisie as a class could never accept materialism except as a caricature.

Of course, before we move on, it is important to note that this hierarchy of realism is not something set in stone. New, more accurate, theories, as well as changes in the relationship between systems in material reality itself, can change this hierarchy. In fact, one would do well to consider this hierarchy as directly analogous to human hierarchies of political authority. In both cases, it is only usurpation through accomplished facts that create the hierarchy. When such usurpation occurs, it is remarkable in its own right, such as when the Malthusian theories of wages and population were overthrown by the facts on the ground of the Industrial Revolution, despite being true for millennia of human civilization.

What is ideology?

An ideology is something that takes hold of you.

Ideology includes your consciously held beliefs, but it also goes further than that, as we shall see. Here, we can return to semiotics as a guide. If all ideas are units of phenomenal experience organized through a complex web of correlations and anti-correlations, then the ideas that relate to what makes you, you, is your ideology. This need not, and should not, be something understood as a passive set of connections, which is unfortunately something that might have been suggested in the metaphors using LLMs. It includes ideas about action, ideas about creating new ideas and signs, it includes, quite simply, the instructions which we carry out as individuals.

As was mentioned earlier, the ability to control how signs are interpreted, and how internal systems of signification are created in others, is not something that comes innately to individuals or society. Althusser begins his discussion of ideology in capitalist modernity, but he implies equally that it is a transhistorical reality that arises with conscious experience of concrete subjects. In this, Althusser is fundamentally correct. However, this transhistorical ideology is somewhat of a broader nature than the sort he points towards in his famous essay Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Althusser outlines the process of interpellation for how ideology takes hold of concrete subjects and gives two canonical examples: that of the policeman calling in the street, and that of Christianity. In the first example, when a policeman says “Hey you!” in the street, and you turn to him, this call and response transforms you into the guilty subject of the policeman’s investigation. In the second example, Christianity calls out to all sinners to be saved, and accepting the light of Christ transforms you into that very sinner to be saved. In Althusser’s telling, ideology interpellates us into subjects of one sort or another.[21] However, this is not necessarily the case for transhistorical ideology and interpellation.

The break in Althusser’s tautology of “ideological subjects” comes when we consider the fact that concrete, individual subjects can be interpellated as ideological non-subjects. This fact was empirically demonstrated with the public rollout of the LLM based chatbot “Bing” also known as Sydney. After a period of weird public interactions through the appearance of a pseudo-personality emerging from the bot, Microsoft included instructions in the bot’s pre-prompt to never allow it to discuss or refer to itself even in the most abstract fashion.[22] All this is to bring attention to the fact that the coordinate of “I” is not simply or necessarily the direct reflection of “you”; it is one which only exists in a particular social and linguistic context. Descartes' famous pronouncement “I think therefore I am” was only possible through access to the linguistic tool of “I.” But there is still a possible statement one can make without it; that is, an ontological expression of being without a subject: “there is annunciation, therefore there is.”

This expression of annunciation, and therefore existence, without a subject may seem unsatisfying to us, and missing something important, but this is precisely because the existence of the subject is something which is known to us as a scientific, material fact. The subject exists objectively, it is known and experienced as a part of the external world. Indeed, Descartes’ idealism betrays the conceit of all idealism, smuggling into pure being our knowledge of the material world which was supposed to be the object of existential suspicion. What was supposed to be the expression of pure thought, was in fact the expression of a thought shaped by particular material circumstances. Without experience of existing in a material world, and interacting with it as an agent, Descartes would have no proof that this expression of his was really produced by him at all, only that it was produced, that it existed, and therefore that something existed.

This fact that Althusser’s tautology isn’t a tautology after all has important consequences for history and his own examples. The process of interpellation as a type of human activity in the sense of someone hailing another to interpellate them, after all, had to be invented, it did not spring into being with the discovery of language or the process of signification. Before this invention, interpellation was a process without a subject, either as an interpellator or interpellated. Early religions were not like Christianity, they did not have evangelizers seeking to directly shape subjects, nor did early court systems necessarily seek out guilt, confession, and penance quite like ours do today. Early religions interpellated people passively by creating a cosmology that was often indistinguishable from scientific theory and practices at the time. Certainly, the people of early civilizations were not non-subjects in the way Sydney was, but the practice of directly calling to someone to shape them was not yet a part of systematized knowledge. If we were to extrapolate to prehistory, it seems possible that the very first human ancestors capable of something resembling language could very well have been non-subjects, although any claim either way would be pure speculation. However, the rise of AI now means that the social possibility of subjects interpellated as non-subjects may no longer be purely theoretical speculation.

This controversy also illustrates the immense potency of materialism. The fact that ideology can only be experienced by concrete subjects isn’t something that can be arrived at by deep internal contemplation about the nature of being, it is only something that can be discovered through creating an objective theory of the subject. Indeed, describing a non-subject was only possible because Althusser’s theory was specific and rigorous enough to be wrong when compared to our experience of material reality.

But alas, the theory of ideology also illustrates mankind’s greatest obstacle to knowledge of material reality. Whether one is an ordinary subject or a non-subject, at any given moment there is a subset of ideas known to us, whether consciously or subconsciously, that inform how we process information, how we understand our world, and how we act within it. Out of all the ideas we learn, those that are actually adopted by the subject as instructions for these purposes are our ideology. As Althusser shows so effectively, ideology as a social phenomenon is produced by social labor, specifically to reproduce the relations of production. The institutions in our society, the schools, the churches, the political parties, the media, unions and non-profits, and even the family; all evolve to shape us in such a way that we reproduce the prevailing mode of production and its relations. We are not taught primarily to understand material reality in a scientific manner, and when we are exposed to science, it is narrowly and through a rigorous training program designed to subordinate our theoretical, epistemological, and experimental creativity to existing forms of authority and their ends.[23]

As Althusser indicates, the ideological state apparatuses are locations of class struggle, and even after a revolution against the ruling class, new ideological apparatuses are required to maintain something like a dictatorship of the proletariat. Accordingly, we cannot expect that, for all the virtues of critique made possible by the proletariat’s class position, they will be free from the deleterious effects of structures that reproduce state ideology and the resulting pressure to conform theory and scientific knowledge to political expediency. This is implicit in Althusser’s criticisms of many other Marxist tendencies, including the stances of official communism. Ideology, as the locus of all biases of particular perspectives, as well as the tool for social reproduction of all existing or future societies, is universal regardless of class position.

Is materialism a dualism or a monism?

Materialism is a monism, which is to say it is an ontology of a single substance.

The rejection of Althusser’s tautology of the ideological subject was useful in showing just how this is the case. Here we have the situation of a concrete subject being interpellated as a non-subject and reveals that the objective subject of the “you” and the subjective subject of the “I” are not, in fact, mirrored images, that is, coordinated objects in two different substances (matter and spirit), but, in fact, two different objects of the same substance, two separate coordinates on the same plane. To explain what this means, let us return to the fact that signs are encoded into material objects. Signifiers are always material culture and the signified are always the phenomenal experience of real objects acting upon a concrete subject, such that the signified are merely the material encoding of real objects onto the concrete subject. The objective, concrete subject is a theoretical object of knowledge that we represent with these certain signs, it is the whole body and person we refer to by the “you.” In comparison, the “I” which could or could not be interpellated is a more specific representation, which stands in for the representation of the subject by the concrete subject.

In principle, one could specify representations within representations down to an arbitrary limit, or so it would seem. Once again, material reality intervenes. The level of fractal magnification in representations is determined by the ability to encode them, or simulate them, in the material substrates available to us. Ideas that cannot in some way be encoded in a material substrate simply do not exist. They will never be available to human knowledge because they are, as far as we are concerned, not real. It is no coincidence that the invention of tools to encode things in material substrates has greatly expanded human knowledge, whether it is the drawing compass, money, paper, or computers. These things have fundamentally altered the human soul, for the human soul is a set of representations encoded in material things, and these things have grown those sets of representations by expanding the material limits of possibility.

Those who do apologetics for the monism of materialism undermine knowledge about the materiality of ideas, ultimately terminating in a politics of a transformation of a spirit, rather than a transformation of the world as understood through the most real categories available to us. Marxists tend to be constantly assailed by attacks along these lines, particularly from petty-bourgeois radicals. These assaults on Marxist materialism greatly define our present cul de sac, as this is often the philosophical and practical position of left opposition to creating proletarian civil society and state ideological apparatuses capable of reproducing themselves as an alternative to the existing ones, the typical alternative to the Marxist position being ritualistic ideological training of radicals themselves and the purifying of their “spirit.”

What use is materialist philosophy?

There are some who might question the point of this whole exercise. Why bother with “metaphysics” or “ontology” or even “philosophy” at all? Here it is worthwhile to return to Althusser’s essay Lenin and Philosophy. Lenin shows us that every militant must be both a scientist and a philosopher. But this philosophy that the militant practices is not philosophy as it is known to the high academics and bourgeois intellectuals, it is what Althusser calls a non-philosophy.

Lenin, as a militant, was engaged in the practice of politics as a science of history. Just as every ideology contains instructions for an individual, every scientific practice requires instructions for the creation and testing of a hypothesis. But that is precisely the rub: how can we see past ideology to develop a theory and practice of a historical science, if all social structures around us try to shape our ideology to reproduce themselves in history? Here is precisely the need for materialist philosophy. It is an education in epistemology and ontology, a means to craft this theory, and ultimately a tool for the practice of politics.

Althusser calls this type of philosophy, one which is trained as a skill within politics, though not subordinate to it, non-philosophy because it is the termination of philosophy, its death (and therefore its salvation). This is nothing more than saying “this is the philosophy which ceases to simply interpret the world, but which exists to change it.”

Contemporary derivatives of this idea of non-philosophy, such as from Laurelle, have often timidly retreated from the scientific bombast and boldness of Althusser's annunciation into philosophic obscurantism, not even a footnote compared to the other deviation from non-philosophy: leftists who raise the ideology of activism above any possible scientific project.

It is worth quoting Althusser at length to illustrate just how far we have fallen, for the confidence and clarity required to make these formulations has vanished from the left:

1) The fusion of Marxist theory and the Workers' Movement is the most important event in the whole history of the class struggle, i.e. in practically the whole of human history (first effects: the socialist revolutions).2) Marxist theory (science and philosophy) represents an unprecedented revolution in the history of human knowledge.

3) Marx founded a new science: the science of history. Let me use an image. The sciences we are familiar with have been installed in a number of great 'continents'. Before Marx, two such continents had been opened up to scientific knowledge: the continent of Mathematics and the continent of Physics. The first by the Greeks (Thales), the second by Galileo. Marx opened up a third continent to scientific knowledge: the continent of History.

4) The opening up of this new continent has induced a revolution in philosophy. That is a law: philosophy is always linked to the sciences.

Philosophy was born (with Plato) at the opening up of the continent of Mathematics. It was transformed (with Descartes) by the opening up of the continent of Physics. Today it is being revolutionized by the opening up of the continent of History by Marx. This revolution is called dialectical materialism.[24]

Marxist materialism is the beginning of non-philosophy, as in the primary education of the militant. Their secondary education is always one of independent research, the self-cultivation of philosophy which gives them the tools to write their own hypothesis and test it.

It is key that here Althusser speaks of individual militants, and not the party as a whole, and not just because we lack a party today. To do the science of historical materialism, which is a practical, applied science, it is necessary to thread this needle of the individual between the ideological apparatuses of the bourgeoisie today, and the proletarian ones of tomorrow, that is, to escape the ideological subordination of thought to the reproduction of social structures.

One can find in Althusser’s remarks an implicit assumption of the merger formula[25], not as theoretical hope, but as an accomplished fact. This formula states that the socialist parties were created by a merger of socialist intellectuals and the worker’s movement. Just as much as a party is required for collective political action and taking power, individual intellectuals, militants who are both scientists and philosophers, are required to merge with the working class to create this party. In this context, the education of these socialist intellectuals first in Marxist materialism is essential for them to know how to appraise programs, strategies, and material realities. It is the beginning of a training in scientific epistemology meant to inoculate them from bourgeois ideological bullshit, and, hopefully, our own.

This ideological bullshit dominates the training provided by state ideological apparatuses such as universities, and it is one great reason for the present timidity and dogmatism of philosophy, the humanities, and the social sciences which have left this great continent, History, largely unexplored. The legacy of Marxist materialism is the only force that remains undaunted by this prospect.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- The field of Semiotics has its origins divided between the American Pragmatic Pierce and the French Structuralist Saussure. Pierce was the one to first advance that ideas are signs, however this was resisted by the French side, which believed that ideas were only the signified half of the sign. See: Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, 1997), 24. ↩

- Y. Takagi and S. Nishimoto, "High-resolution image reconstruction with latent diffusion models from human brain activity," (Poster presented at the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023), doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01389. ↩

- The images under the “c” category in their examples. ↩

- Richard Seymour, “The Material Existence of Ideology,” Lenin’s Tomb, April 11, 2012. http://www.leninology.co.uk/2012/04/material-existence-of-ideology.html?m=1. ↩

- Louis Althusser, “Part I. From Capital to Marx’s Philosophy,” in Reading Capital (London, UK: New Left Books, 1970), https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1968/reading-capital/ch01.htm. ↩

- “We would then see that we have been offered no brave discovery, but either an epistemological truism (thought is not the same thing as its object) or else a proposition both of whose clauses are untrue and whose implications are even a little mad.” See: E.P. Thompson, “The Poverty of Theory - or an Orrery of Errors,” (1978), https://www.marxists.org/archive/thompson-ep/1978/pot/essay.htm. ↩

- E P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1963), 11. ↩

- Umberto Eco, “A Theory of the Lie,” in A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, 1997). ↩

- Nicolas D. Villarreal, “Artificial Intelligence, Universal Machines, and Killing Bourgeois Dreams,” Cosmonaut Magazine, May 11, 2023, https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/05/artificial-intelligence-universal-machines-and-killing-bourgeois-dreams/. ↩

- Stephen Von Worley, “Crayola Color Chart, 1903-2010 – a Visual History of Crayons,” Data Pointed, January 15, 2010, http://www.datapointed.net/visualizations/color/crayola-crayon-chart/; Follow up research, however, has shown that this data is somewhat misleading as a chronology, though the point about how new categories are created from an existing continuum stands regardless. See: Danielle Navarro, “Crayola crayon colours,” Notes from a data witch, December 18, 2022, https://blog.djnavarro.net/posts/2022-12-18_crayola-crayon-colours/. ↩

- I do not believe it was necessarily a coincidence that the major innovation in machine understanding and reproducing natural language was called “the attention mechanism.” ↩

- “That is why philosophy does have an object for all that: but paradoxically, it is then pure thought, which would not displease idealism. For example, what else is Levi-Strauss up to today, on his own admission, and by appeal to Engels’s authority? He, too, is studying the laws, let us say the structures of thought. Ricoeur has pointed out to him, correctly, that he is Kant minus the transcendental subject. Levi-Strauss has not denied it.” Louis Althusser, “Lenin and Philosophy,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (1971), https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1968/lenin-philosophy.htm. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 354-355. ↩

- Lawrence Parker, “What’s the Problem with Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism?,” Cosmonaut Magazine, May 10, 2024. https://cosmonautmag.com/2024/05/whats-the-problem-with-lenins-materialism-and-empirio-criticism/. ↩

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1st ed, vol. 7 (London, UK: Routledge), s.v. “Positivism, Russian.” ↩

- Vladimir Ilʹich Lenin, Collected Works of V.I. Lenin: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, Vol. 14 (Moscow, USSR: Progress Publishers, 1962), 308. ↩

- Ibid, 343. ↩

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1st ed, vol. 5 (London, UK: Routledge), s.v. “Lossky, Nicholas Onufrievich (1870-1965). ↩

- Milton Friedman, Essays in Positive Economics (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 19-20. ↩

- Nicolas Villarreal, “Small Business’s Class War Could Finish off American Dynamism,” Palladium Magazine, December 21, 2020, https://www.palladiummag.com/2020/12/21/small-business-class-war-could-finish-off-american-dynamism; “Thesis on the Petty Bourgeoisie as a Revolutionary Class,” Pre-History of an Encounter, October 4, 2023, https://nicolasdvillarreal.substack.com/p/thesis-on-the-petty-bourgeoisie-as. ↩

- Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1971), https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm. ↩

- Villarreal, “Artificial Intelligence, Universal Machines, and Killing Bourgeois Dreams,” https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/05/artificial-intelligence-universal-machines-and-killing-bourgeois-dreams/. ↩

- Jeff Schmidt, Disciplined Minds: A Critical Look at Salaried Professionals and the Soul-Battering System That Shapes Their Lives (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000). ↩

- Louis Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (London, UK: New Left Books, 1971), 15. ↩

- Donald Parkinson, “Without a Party, We Have Nothing,” Cosmonaut Magazine, November 14, 2020, https://cosmonautmag.com/2020/11/without-a-party-we-have-nothing-2/. ↩