It's looming before us: the dark road ahead. A world choked by fires and floods, ashes and dust, hatred and death. Even the best of us are afraid to express hope. It’s out of style. Instead, we embrace dark irony and bitter laughter, dragging our feet through a life designed to crush our will.

How can a small movement challenge the Leviathan? How can it find strength in its independence? How can it topple a power that seems omnipotent and achieve a revolution?

In 2024, these tasks may seem hopelessly difficult to socialists in the United States. But defying the powerful has never been easy, and we will always have lessons to learn from our predecessors. One of the most important, yet also misunderstood, is the American abolitionist movement.

It’s easy enough to celebrate abolitionists for their righteous principles: activists of every stripe invoke their legacy. Yet abolitionists and their Radical Republican allies were more than just moral idealists. They were also cunning revolutionary strategists. Using principled independent politics, they successfully attacked America’s slaveholding oligarchy and the two-party system that protected it. Their insights and debates have tremendous relevance for modern socialists, because abolitionism helped to ignite the most important revolutionary rupture in U.S. history: the Civil War and the downfall of chattel slavery.

Lesson 1: Be a principled minority

Numbers should not be looked to so much as right. The man who is right is a majority…Though he does not represent the present state, he represents the future state.”

In the years before the Civil War, being an abolitionist meant fighting the world. Even in the Northern states where slavery was gradually phased out, abolitionists had to grapple with a virulently racist white male electorate. Yet even more importantly, they challenged an entire political order that ruthlessly protected slavery and the planter aristocracy of the South.

Slavery was embedded in the U.S. Constitution. Its infamous Three-Fifths Clause allowed Southern planters to count their own slaves to inflate their representation in Congress. Meanwhile, the Electoral College was created in part to strengthen the slave states: a nationwide popular vote would have disadvantaged them, with their massive nonvoting slave populations. The Fugitive Slave Clause required free states to “deliver up” anyone who escaped from bondage, preventing them from offering sanctuary. Crowning it all, the federal government had explicit authority to "suppress insurrections,” including slave rebellions. Conceivably, any white male citizen could be legally obligated to slaughter revolting slaves if the federal government conscripted them into a militia and sent them marching south.

The Senate was not initially expected to favor the South, but its anti-majoritarian structure made it easy enough for slaveholders to co-opt. The planters established a norm of “Senate parity,” requiring new slave states and free states to be admitted to the Union together in pairs—even though the slave states always had smaller voting populations. It was a good deal for the slaveholders: their votes counted for more.

With their combined influence over the Senate and presidency, the slaveholders dominated executive appointments, holding the majority of Supreme Court seats and controlling the highest offices of the executive branch. Even John Adams of Massachusetts—the only Founding Generation president who did not own slaves—offered 51% of his executive appointments to men from the South.[1]

Washington, D.C. was a Southern city and it became a center of the U.S. slave trade. Slave pens lined the National Mall and processions were led about in shackles, bound for the cotton plantations of the Deep South. Everything was visible from the windows of the U.S. Capitol building.

By the 1820s, a two-party system of Whigs and Democrats was developing, nurtured by the brilliant New York politician Martin Van Buren. Van Buren’s explicit goal was to use the excitement of party politics to distract the masses from more dangerous conflicts over slavery. Whigs and Democrats would have fiery conflict and genuine power struggles—but both sides suppressed opposition to America’s true ruling class: the planters of the South, the Slave Power.

Yet in the same decade, a subversive threat was quietly taking root. Black abolitionist groups were organizing across Northern cities and in Baltimore, exhausted with both Northern racism and Southern intransigence on slavery. Their goal was simple: immediate abolition of slavery without compensation to owners, and without any colonization schemes to send Black Americans “back to Africa.” This movement promoted Black pride and self-improvement, solidarity between free Blacks and their enslaved “brethren,” and open resistance to slavery. However, abolitionists also fought for full equality within the United States: birthright citizenship and a multiracial republic. No one embodied the new spirit of militancy more than the free black Bostonian David Walker, who wrote in his influential 1828 Appeal:

America is more our country than it is the whites -- we have enriched it with our blood and tears…will they drive us from our property and homes, which we have earned with our blood?

A small number of white Americans began to organize alongside Black abolitionists. Chief among them was William Lloyd Garrison, who published the weekly abolitionist paper The Liberator. Garrison and his associates radicalized white antislavery advocates, setting the stage for an interracial antislavery society that fought for immediate abolition and Black citizenship. Dozens of local groups sprang up rapidly across the North. In December 1833, their delegations convened in Philadelphia to form a nationwide organization: the American Antislavery Society (AASS).

By 1838, AASS had exploded to over 1,000 local chapters and about 250,000 dues-paying members—over 1% of the US population (though still a hated minority). The majority of AASS members came from decidedly humble occupations. They were farmers, mechanics, artisans, and journeymen, and they did not care about appeasing “the majority.” They were determined to shatter the nation’s silence on slavery.[2]

In the words of abolition scholar Manisha Sinha, “immediatist” demands for uncompensated abolition and Black citizenship gave abolitionism its “programmatic clarity.”[3] These were shocking, unpopular demands that provoked disgust in most white Americans at first. Yet they were also powerfully effective. By embracing immediatism, white abolitionists could earn the trust of Black Americans who did not want to be deported from their homes or watch their children serve 25-year “apprenticeships” to their former enslavers. This set the stage for unprecedented interracial cooperation and a movement with clear strategic goals. Instead of appeasing wavering, indecisive white moderates, the AASS was growing into a hardened abolitionist minority that fought on the bleeding edge of antislavery politics.

Lesson 2: Agitate the Congress

In 1837, John Quincy Adams brought a petition to the House floor. It was one of hundreds that the former president (now a Massachusetts representative) had shared. His petitions all focused on a single demand: abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C. In the federal district, there were no constitutional barriers to freeing slave “property”—and why should such an atrocious institution be permitted in the nation's capital?

Abolitionists were, of course, the true ringleaders behind these petitions, working closely with Adams every step of the way.[4] Their rabble-rousing had made quite a splash, and the House had already imposed a gag rule banning all discussion of antislavery petitions. Adams worked diligently to subvert the gag, and today he was merely asking a question about the rule’s scope: would it apply to a petition signed by slaves?

The planters flew into a hysterical rage. They screamed for the petition to be burned on the House floor and suggested that Adams should be indicted for inciting slave insurrection. Then, Adams calmly announced that the slave petition actually opposed abolition, and the truth became clear. In modern terms, Adams was trolling: he had probably fabricated the surreal petition. Even if it was authentic, he was deliberately using it to enrage and disorient the planters, who spent the next week demanding his censure. Adams ridiculed their allegations, denounced the immorality of slaveholders, and even defended the right of slaves to petition. In the end, the planters failed to secure Adams’ censure, but their hysterical overreaction worked wonders at promoting antislavery sentiments in the North.[5]

Modern pundits would have condemned Adams’ principled stand as useless theatrics. Adams and the abolitionists advising him knew better. “Agitating the Congress” did not usually result in immediate legislative gains (slavery was not abolished in D.C. until 1862). Even so, it was stunningly effective at igniting the power of mass politics. As one leading AASS member explained to Adams, abolitionists did “not expect so much to convert members of Congress as their constituents.”[6] Others noted that with a single speech, an anti-slavery congressman could “do [more] for the A.S. cause…than our best lecturers can do in a year.”[7] Congress was not a place to quietly “build power” in the shadows. It was a platform for nationwide agitation, a place where antislavery populists could boldly confront elitist planters, stirring the pot for a crisis. Adams' reach was so wide that it penetrated Southern newspapers, providing a young Frederick Douglass with his first exposure to the Northern abolitionist movement. Douglass would later recall the “joy and gladness” of reading Adams’ words aloud to fellow slaves, before he escaped to the North in 1838.[8]

Lesson 3: Praise and criticize electeds

Even though Adams worked closely with abolitionists to challenge the Slave Power in Congress, the “Old Man Eloquent” was not an abolitionist himself, and he sometimes took conciliatory stances. He insisted that he was fighting the gag rule merely to defend free speech and did not personally support immediate abolition in the capital. This was a grave disappointment for abolitionists, who viewed District emancipation as a non-negotiable “test question.”[9]

Younger anti-slavery Whigs soon began to join Adams. carving out a small foothold in the House. But abolitionists soon noticed that these representatives were also compromised by their obligations to the proslavery Whig leadership. This often required them to support slaveholding presidential nominees and House Speaker candidates—horrifying the abolitionists.[10]

AASS members did not stifle their discontent. Their publications had a simple philosophy: whenever an antislavery politician makes a principled stand against the Slave Power, lavish them with praise. When they fall short, criticize them harshly and publicly.[11] Every step of the way, encourage them to “stoke the abolition fire in the Capitol.”[12]

To that end, abolitionists also began developing a sophisticated "Liberty Lobby" in Washington, D.C. They helped antislavery congressmen find openings to confront the Slave Power, assisted them with research and speechwriting, and strategized with them to counter political attacks. Abolitionist criticism could be provocative at times, but gradually, abolitionists won the respect of their elected allies and became increasingly influential. Anti-slavery agitation was politically dangerous, but the congressmen also found it exciting. They enjoyed the opportunity to voice their convictions and even win celebrity status in the North.[13]

Today, leftists are often afraid to criticize their allies in elected office or recommend confrontational tactics. We would do well to learn from the abolitionists, who had a subversive vision of oppositional politics—and successfully made it happen.

Lesson 4: Fight the two-party system

As the 1830s progressed, the AASS became increasingly polarized over political strategy. The organization’s early electoral work relied on “interrogation”: asking candidates from both parties to fill out policy questionnaires on slavery and then making endorsements based on their responses. To a certain degree, this approach encouraged political independence by asking abolitionists to base their votes on anti-slavery principles instead of party loyalty. But “interrogation” also turned abolitionists into helpless bystanders when candidates refused to answer their questions, gave evasive responses, or betrayed their antislavery commitments after being endorsed and elected. Predictably, some members of the AASS began demanding a more ambitious intervention in electoral politics. They wanted to build a “Liberty Party”—an independent and explicitly abolitionist political party that would would contest elections.[14]

A different tendency, led by William Lloyd Garrison, pushed in exactly the opposite direction. To Garrison, the greatest obstacle to abolition was not the two-party system: it was the entire constitutional order. He argued (with overwhelming evidence) that the Framers of the Constitution had deliberately protected slavery in numerous ways. Therefore, he argued that abolitionists should reject direct participation in the electoral system (i.e. voting and running for office) on moralistic grounds. Electoral work would require abolitionists to pledge loyalty to the Constitution and its proslavery provisions, betraying their antislavery principles. Instead, “Garrisonians” attempted to convert proslavery citizens through journalism, “moral suasion,” and nonviolent protests, while also continuing to lobby and petition. They hoped to change politics primarily through indirect influence, by embodying perfect antislavery purity to the rest of society. Political leaders and the voting public might never become abolitionists, but they could still be guided toward stronger antislavery stances.

It was a strange blend of radical goals and milquetoast methods. By the late 1830s, Garrison had embraced a form of Christian anarchist pacifism, denouncing all human government as sinful. He supported women's rights, became increasingly anticlerical, and in 1842, he called for the North to secede under the slogan “No Union with Slaveholders.”[15] However, his followers continued to abstain from voting and had no desire to challenge the two-party system. Because they viewed electoral work as inherently corrupting, they denounced Liberty Party supporters as sellouts who would inevitably degrade the abolitionist cause. But simultaneously, Garrisonians hoped that the non-abolitionist parties would eventually address slavery through negotiations in Congress. They worried that a third party would reduce their movement’s moral influence on established politicians.[16]

Ironically, Garrison’s radical abstentionism may well have had a conservatizing influence on pro-electoral abolitionism. When the pro-electoral faction split from the AASS in 1839, Garrison bitterly rejected the nascent Liberty Party. This ceded ground to church-oriented abolitionists who rejected Garrison’s views on women’s rights (although the dynamic was quite complicated, and some women’s rights advocates supported the Liberty Party). Lacking monolithic support even from abolitionists, the new party would struggle to achieve anything in the hostile two-party system.

Lesson 5: Use disruptive electoral tactics

Against all odds, the Liberty Party achieved quite a bit. They pioneered an electrifying language of antislavery populism, planting the seeds for much larger anti-slavery parties. They understood that the Slave Power would not be brought down by Whigs or Democrats: it would be defeated by a new Liberty Power, forged in struggle by dedicated antislavery partisans. “Liberty men” were determined to attack slavery not just through moral suasion, but through ruthless political action.[17] This meant attacking the slaveholding oligarchy on anti-elitist grounds, portraying both major parties as subservient to the planter aristocracy. It meant seeking inroads with Northern whites by arguing that slavery also degraded free labor and denouncing the planters for warmongering in their relentless efforts to acquire new slave territory. In an era of toxic masculinity, Liberty partisans even found cunning ways to appeal to men’s dignity and pride. They described Northern pro-slavery politicians as “doughfaces:” cowardly sycophants who willingly groveled to the cruel Slave Power. The Liberty Power, on the other hand, was scrappy, self-reliant, and independent. Becoming an abolitionist made you a better man: kinder and more courageous.

The Liberty Party platform did not call for the federal government to impose immediate abolition on the Southern states. That approach was widely viewed as unconstitutional, and virtually everyone understood that it would require a bloody invasion. Instead, they demanded an “absolute and unqualified divorce of the General Government from slavery.”[18] The federal government would immediately abolish slavery in the capital and all territories under its jurisdiction. There would be no new slave states and no more federal support for the capture of fugitive slaves. Abolitionists also envisioned using the Interstate Commerce Clause to ban slave trading across state boundaries, and even using federal patronage to promote Southern anti-slavery movements.[19] With an effective quarantine in place, Liberty leaders hoped that “State after State will speedily and voluntarily emancipate.”[18] For their part, the planters also believed that the Liberty platform would lead to the destruction of slavery by nonmilitary means, and fervently opposed it.[20]

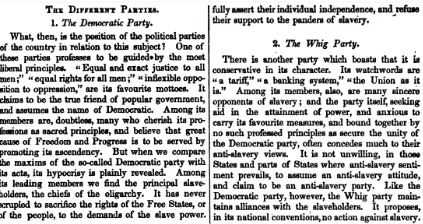

Being critical of the establishment parties did not preclude a nuanced analysis of their differences. One popular Liberty pamphlet included a side-by-side comparison of the Democrats and Whigs, contrasting the Democrats’ populist rhetoric with the Whigs’ more conservative temperament. Northern Democrats received special vitriol for embracing the “jackall’s share” as race-baiting toadies for Southern planters. But the Whigs are not let off the hook. Although the Whig Party had “many sincere opponents of slavery” in its ranks and even adopted antislavery rhetoric in certain regions, they made no antislavery commitments in their nationwide platforms and messaging. The party’s national leadership, both within Congress and without, treated slaveholding Whigs with complete deference. Therefore, Liberty partisans were “constrained to think…that all expectation of efficient anti-slavery action from the Whig party…will prove delusive.”[21]

Liberty members continued their principled engagement with antislavery Whigs, but they also began contesting elections in their own right. Despite the hostile U.S. electoral system—with its emphasis on plurality rule and winner-take-all elections—Liberty members became adept at targeting weak spots to challenge two-party hegemony. The key was often to leverage the balance of power between the major parties.[22]

An excellent example of this approach is the party’s ruthless exploitation of rerun elections. In every New England state except Rhode Island, candidates for state office and the U.S. House were required to receive an absolute majority vote (instead of a plurality) to win election. If no candidate received this majority, the election would simply be run again until a candidate finally emerged victorious. The norm was for poorly-performing candidates to drop out so that voters could coalesce around a winner—but Liberty men were happy to erode this norm. Their candidates forced rerun after rerun, refusing to concede even when they only took small percentages of the vote. Empty House seats and gridlocked electoral contests brought useful publicity to the party, and often forced the Whigs and Democrats to converge behind a single candidate. This in turn boosted the Liberty Party’s argument that both major parties were ultimately loyal to the Slave Power.[23]

It is true that this unique type of election no longer exists in the United States (with the promising exception of House speakership contests). Even so, we can still draw inspiration from the Liberty Party’s relentless independence, its embrace of disruptive tactics, and its eagerness to polarize society against both major parties instead of toadying up to the Democrats. Modern socialists could cause similar electoral mayhem by refusing to endorse establishment primary nominees, continuing to the general election as a “sore loser,” or even placing a separate, independent “backup candidate” on the ballot in the 48 states that ban sore loser campaigns.

The Liberty Party’s electoral performance improved gradually but significantly in the 1840s. Federal victories had not come yet, but they won state legislative seats and occasionally even gained the balance of power between the two major parties. Throughout the North, Liberty activists fought to repeal discriminatory “black codes,” win Black suffrage, and desegregate public schools and railroads—prefiguring the Civil Rights Movement over a century later. These efforts were particularly important to Black Liberty members, and the party managed to acquire a substantial cadre of Black leadership such as Henry Bibb and Henry Highland Garnet.[24] The party even made some inroads with labor activists, denouncing slavery for degrading free labor and advancing pro-worker reforms.[25]

Grassroots slave resistance also created new opportunities for political abolitionists. Among the most important of these was the Creole case of 1841, when over 120 American slaves revolted on a ship bound for New Orleans in the profitable interstate slave trade, sailing to freedom in the Bahamas. In the U.S. House, the Ohio anti-slavery Whig Joshua Giddings worked closely with abolitionists to deliver a series of speeches defending the uprising. He pointed out that the revolt took place on the seas outside state boundaries, and therefore violated no state laws. Despite the carefully-formulated boundaries of this argument, the very implication that slave revolts could ever be legitimate enraged pro-slavery representatives. They rapidly voted to censure Giddings without even giving him a chance to defend himself. Under intense pressure, Giddings resigned from office and went back to his district in Ohio to campaign for reelection. This was his chance to prove that his constituents supported his antislavery cause.

Giddings’ own Whig party abandoned him, rushing to distance itself from his abolitionist agitation. By contrast, the Ohio Liberty Party backed him to the hilt, recognizing the special election as a referendum on slavery. Giddings won reelection by an overwhelming margin, and it became clear that the debacle had profoundly helped the abolitionist cause. Anti-slavery voters were outraged at the South’s overreach and began to abandon their old party loyalties.[26] Although Giddings remained a Whig for the time being, the old two-party system was finally beginning to unravel.[27]

Lesson 6: Don’t avoid national politics.

Today, the American Left often downplays the importance of presidential elections in favor of hyperlocal organizing or insists on supporting the Democratic nominee to keep reactionaries out of power. In contrast, Liberty partisans understood the tremendous importance of presidential elections in shaping popular consciousness. They insisted on running their own candidates to present an independent opposition, even when they had no chance of victory.

In the 1844 presidential elections, the Liberty Party embraced a spoiler role to accelerate political tensions. Throughout the election, Whigs angrily accused the Liberty candidate James Birney of splitting the antislavery vote and secretly working for the Democratic candidate James K. Polk. A Tennessee planter and aggressive slavery expansionist, Polk openly planned to annex Texas as a slave state, stoking war with Mexico. The Whig candidate Henry Clay was quite different. He was a planter from Kentucky who preferred to hedge and equivocate about Texas annexation.[28]

Liberty partisans would have none of it. If Polk won, one party leader insisted, “all the Whigs of the North will be opposed of course to the extension of slavery & many of the democrats … Whereas if Clay is elected he will carry nearly all the North with him.” The “out & out fiend” Polk was better than an “intriguer” like Clay.[29]

The fiend won out. Birney received just 2% of the popular vote (still a near-tenfold increase over his previous performance in 1840). Liberty votes formed more than the balance of power in New York, which could have swung the entire election to Clay. The Whigs raged against Birney and blamed him for every misfortune to come. Liberty men replied that the Whigs had dug their own grave by nominating a “hoary” old slaveholder. They stayed strong, retaining hope that Polk would spark Northern opposition in a way the more deceptive Clay never could.[30]

He did. During his term, Polk annexed Texas, sparked his precious war, and carved up Mexico from the Rio Grande to the California shore. This ignited a Northern antiwar movement, and when it became clear that Polk’s vast conquests were irreversible, an even more explosive debate began over the future of slavery in the new territories. Party discipline continued to break down, and Liberty men joined insurgent coalitions with anti-slavery Whigs and even Democrats, running independent antislavery candidates for office. By 1848, this burgeoning movement had converged to form the Free Soil Party, a big tent third party dedicated exclusively to preventing the expansion of slavery. A vast majority of the Liberty Party’s supporters merged into the new party, hoping to guide it towards stronger antislavery positions.

Although the Free Soil Party only gathered about 10% of the 1848 presidential vote, it sent roughly nine members to the House of Representatives, controlling the balance of power between the major parties. Taking a page out of the Liberty Party playbook, they sparked riotous chaos in the House speakership elections, insisting that any speaker candidate meet a set of non-negotiable antislavery demands. They forced 63 ballots and ground proceedings to a halt for three weeks, until the major parties finally agreed to a plurality vote, which handed the speakership to a slaveholding Georgia Democrat. From a conventional standpoint, the Free Soilers’ gambit had failed, but once again, antislavery partisans had humiliated the establishment and smashed their way into the national spotlight. Six years later, their Republican successors took control of the speakership.

Lesson 7: Rise to the Jerry Level.

Many abolitionists also enjoyed pursuing certain underground extracurricular activities. For their part, Liberty supporters accepted the Constitution more than Garrison did, but they were happy to create certain loopholes. The 1844 Liberty Party platform declared that on the basis of “natural rights,” the Fugitive Slave Cause was “utterly null and void” whenever construed to require the surrender of a fugitive slave.[31] Underground Railroad work was never an official party activity, but Liberty members both Black and white widely engaged in it—including party leaders.[32]

The party’s “natural rights” carveout most likely reflected the influence of a minority tendency in the Liberty Party: the radical political abolitionists (RPAs). The RPAs were a presence in the Liberty Party from its inception and took over the party completely after the majority of Liberty members merged into the new Free Soil Party in 1848. Today, RPAs are best remembered for their eccentric patron Gerrit Smith, one of the richest men in New York and a billionaire in modern dollars. Smith’s thesis was simple. Slavery was against the natural law of universal human rights and completely illegitimate no matter where it took hold. Smith would be more than happy to abolish slavery through direct federal legislation. He felt that the Constitution should be read as an anti-slavery document through a dynamic interpretation of its liberal principles and also because the Constitution had no authority to legalize slavery in the first place. Pro-slavery laws were not laws at all, but mere “enactments” to be “trampled underfoot.”[32]

Modern cynics might dismiss these words as empty posturing, but the RPAs lived up to their powerful rhetoric. More than any other abolitionist tendency, they risked their lives in direct action against slavery. While Garrisonians emphasized “moral suasion” against slavery in the North, RPAs frequently went south to attack slavery on its home turf, often with Smith’s financial assistance.[32] RPA combativeness was of course shaped by Black abolitionists, and many, including Frederick Douglass, joined the tendency.[33]

One stunning example of RPA-linked militancy is the partnership of Thomas A. Smallwood—a free Black abolitionist minister—and Charles T. Torrey, a white Liberty Party lobbyist and journalist from Massachusetts. In 1842, they launched an audacious Underground Railroad line centered in Washington, D.C., capital of the Slave Power. With wagons, safe houses, and a clandestine support network, they helped hundreds of slaves in the region escape to freedom in Canada and the North. They often worked to liberate people enslaved by high-ranking government officials and Southern members of Congress. It was nothing less than psychological warfare against the ruling class. Torrey and Smallwood knew the escapes would drive slaveholders into hysterics and help antislavery legislators “agitate the Congress.” Women, slaves, and free Blacks all played indispensable roles in this subversive multiracial network.[34]

The work cost Torrey his life. Arrested in 1844, he was sentenced to six years of hard labor. In the harsh prison conditions, he died from tuberculosis in 1846. Smallwood evaded arrest but was forced to flee to Canada. But the network they built in Washington outlived them, and the Underground Railroad continued to grow.

In April 1848, 77 slaves in Washington attempted to escape on a schooner called the Pearl, assisted by RPA organizers. Many of their enslavers were Washington political elites, including Polk’s Secretary of State. Tragically, the vessel was intercepted and most of the escapees were later sold south. Meanwhile, thousands of enraged pro-slavery residents rampaged through the capital, threatening ship captains who were arrested for assisting the plot and stoning the office of a Liberty-aligned newspaper.[35] These anti-abolitionist mobs were a common occurrence in antebellum America, but contrary to popular stereotypes, the primary ringleaders were not “poor whites.” Often the mobs were filled with respectable men such as bankers, politicians, and law enforcement.[36]

Now abolitionists had sparked chaos in the nation’s capital with the Free Soiler threat rising at the exact same time. The planters decided that it was time to crack down hard. After the botched House Speaker election of 1849, the Whigs and Democrats came together in a bipartisan orgy of proslavery concessions, dubiously described as the “Compromise” of 1850. They voted to allow “popular sovereignty” votes on slavery in all of Polk’s conquests except California, gave slaveholding Texas a $10 million bailout, and passed an extreme Fugitive Slave Act. Federal commissioners were now authorized to round up alleged fugitives and return them to slavery without any trial or testimony, terrorizing free Blacks and escaped slaves alike. Commissioners received five dollars for each slave they released and ten for each they remanded to bondage. The bill criminalized all humanitarian assistance to fugitive slaves, and federal marshals received authority to knock on any Northern citizen’s door and force them into a slave-hunting posse.[37]

But there was a resistance, a real resistance. Although many white Northerners embraced the “compromise,” many others were enraged by its provocations. Twenty years of abolitionist rabble-rousing had made a real mark on public opinion, and these intrusive new rules hit far too close to home. As one Free Soiler representative explained in the House:

While I am forbidden by law of Congress to give a cup of water or a crust of bread to the hungry and thirsty fugitive, or commanded to lay violent hands on his person [to return him to bondage]… rest assured sir, I shall treat all such laws with contempt. I shall trample them under my feet, as an outrage on humanity, and an insult to God.

—Charles Durkee of Ohio[38]

It began with grassroots resistance in Black Northern communities. Since the 1830s, Black abolitionists and their sympathizers had been forming “Vigilance Committees” to protect escaped slaves and the wider Black community from slave catchers. Now their work kicked into overdrive, and dramatic confrontations to prevent fugitive slave extraditions became more and more frequent. In the 1851 “Christiana Resistance,” a community of armed Black men and women in Pennsylvania successfully defended four fugitive slaves from capture, fighting off a federal marshal and killing the slaveholder Edward Gorsuch.

Weeks later, Liberty Party members and a local vigilance committee staged the even more spectacular “Jerry Rescue” in Syracuse, New York. Federal marshals had arrested the fugitive slave William Henry (widely known as “Jerry”) and planned to return him to bondage. As local citizens witnessed the brutality of his arrest and his courageous struggle to escape, they erupted in outrage. Rallied by the abolitionists, an interracial mob of 2,500 people stormed the police station where Jerry was being held, and undaunted by pistol fire they freed him from the marshals. From there, he was spirited away to safety in Ontario, Canada. He was never recaptured.

The times were changing, and abolitionists were leading mobs of their own now. Anti-slavery politics had gained authentic, popular support from the most unexpected sections of society. Where white Northerners had previously viewed slaves with utter scorn and indifference, they now could feel sympathy and see common interests. The Fugitive Slave Act had brought the brutality of slavery far too close to home to ignore. Meanwhile, the planters’ dream of expanding slavery to the Western territories was a threat to their own ambitions. By and large, white Northerners did not want to work as degraded slave catchers and plantation overseers for pompous Southern aristocrats. They wanted small family farms of their own, where their lives would be humble but dignified and free—though it must be said that this dream was also based on the genocide of indigenous nations.

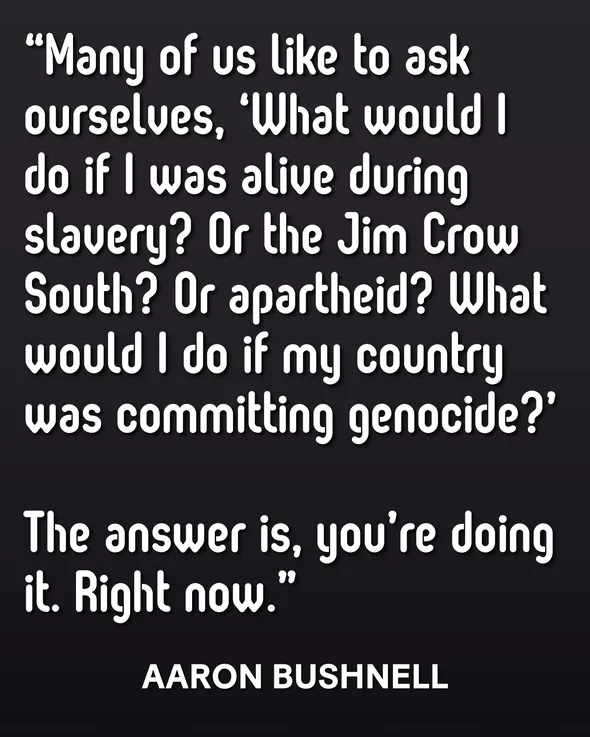

For the rest of the 1850s, abolitionists periodically celebrated the rescue, calling on citizens to rise to “the Jerry Level”: to defy tyranny and to risk their own freedom for the freedom of others. Many Northerners did help in the ways that they could, both large and small. The Underground Railroad became an increasingly public mass movement, supported by donations, bake sales, and handmade crafts.

Despite all the despair that threatens to suffocate us, we too must rise to the Jerry Level. Here’s to our comrades who are doing it. Right now.

Lesson 8: Seize power as an independent party.

At a Pittsburgh convention hall in 1852, Frederick Douglass took to the stage to address the Free Soil Party. As a delegate and recording secretary, he delivered one of the most audacious speeches of his career:

Gentlemen ... I have come here, not so much of a free soiler as others have come. I am, of course… [for] damaging slavery in every way I can. But my motto is extermination ...not only in California but in South Carolina … Slavery has no rightful existence anywhere. The slaveholders not only forfeit their right to liberty, but to life itself.[39]

The crowd broke into applause. Douglass further elaborated:

The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers.[7]

The crowd roared with laughter. This was not the cautious tone of the original Free Soil Party. In 1848, they had selected Martin Van Buren as their presidential candidate, hoping that he would help attract Democrats to their coalition. “The Little Magician” Van Buren had done more than anyone to consolidate the pro-slavery two-party system, but in time he recognized the necessity of co-opting the North’s anti-slavery sentiments. He cynically viewed the Free Soil Party as a temporary means to pressure the Democrats so as to better address sectional tensions. Immediately following the election, he abandoned the Free Soilers and returned to the Democratic fold, taking his supporters with him. In the following years, the Free Soilers had tried to form state-level coalitions with Whigs and Democrats, but faced similar betrayal and frustration. Both major parties embraced the Fugitive Slave Act—denouncing “slavery agitation” in their official 1852 platforms.[40]

In the face of these setbacks, Douglass made the path forward clear:

I want always to be independent, and not hurried to and fro into the ranks of Whigs or Democrats. It has been said that we ought to take the position to gain the greatest number of voters, but that is wrong … It was said in 1848 that Martin Van Buren would carry a strong vote in New York; he did so but he almost ruined us … he regarded the Free Soil party as a fatling to be devoured. [Great laughter.] [41]

Douglass continued:

Numbers should not be looked to so much as right. The man who is right is a majority. He who has God and conscience on his side, has a majority against the universe. Though he does not represent the present state, he represents the future state. If he does not represent what we are, he represents what we ought to be.[7]

In the 1852 election, the Free Democratic presidential candidate received just 5% of the vote. Still, Joshua Giddings successfully won reelection despite an aggressive gerrymander of his district, and Gerrit Smith won a House seat as the most radical abolitionist ever elected to Congress. After a decline in 1850, the Free Democratic congressional bloc expanded to seven members—and the Whig Party was rapidly deteriorating.

To dismiss modern third party efforts, critics often argue that the Republican Party only succeeded because of the Whig collapse. This is not incorrect, but it misses the wider context: the Whigs did not die of “natural causes.” They were eroded by twenty years of anti-slavery agitation, carried out by the AASS, the Liberty Party, and the Free Soilers. The anti-slavery movement had driven them ever closer to the confidently pro-slavery Democratic Party, which made them more irrelevant with each passing day. When the South tried to open the Kansas and Nebraska territories up to slavery in 1854 through “popular sovereignty,” it was the Free Soil congressmen who rallied millions of Americans in opposition. They became founders of the early Republican Party and leaders of its abolitionist-inspired Radical faction.

The Republicans were a broad coalition ranging from moderate conciliators such as Lincoln to radical egalitarians like Thaddeus Stevens and Ben Wade. But even the most cautious Republicans were firmly committed to building an independent anti-slavery party that would take power and govern the Union. In this way, Republicans were far more radical than modern leftists who strive to “realign” ruling class parties. They were also intransigent in their complete refusal to accept any new slave states, which was widely viewed as a long-term path to ending slavery.

The planters, meanwhile, embraced a far darker extremism. They longed to seize vast swaths of Latin America like Cuba and Mexico, adding them to the Union to forge a continental slave empire. They invaded Nicaragua with brutal mercenaries, bludgeoned an antislavery Republican in the Senate, and terrorized antislavery settlers in “Bleeding Kansas.” Then the slaveholder Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott decision, announcing that Black Americans could never be citizens, and barring the federal government from prohibiting slavery in the territories. A storm was gathering: Republicans flatly rejected the ruling and made clear that they would not obey it.

The Northern masses had gained strength and conviction. They rallied around the Republican Party; they continued to support the Underground Railroad, and they prepared themselves for the trials to come.

And a few of the bravest marched on Harpers Ferry.

Lesson 9: Finish the Civil War.

There is war because there was a Republican Party. There was a Republican Party because there was an Abolition Party. There was an Abolition Party because there was Slavery.

You know what followed. The Republicans were determined to consolidate their “political revolution.” They took the House in 1856 and the presidency in 1860, protected by their vast paramilitary “Wide Awake” units. The South seceded, unwilling to accept even a temporary delay to its expansionist ambitions. The war began, and then at last the slaves seized their chance to strike for freedom.

In the end, the planters lost the war, shattered and disgraced, never again to rule the United States as the “Slave Power.” The Constitution was revised to incorporate the core demands of abolitionism: immediate, uncompensated emancipation and equality under the law. All of this was a triumph of the abolitionist dirty break: the decades-long struggle to break up the proslavery two-party system by practicing independent politics while also supporting antislavery dissent within the major parties.

Yet true equality and full emancipation remain a distant dream. The Northern capitalists cut a deal with the remnants of Southern reaction. They withdrew from the South; they allowed the atrocious subjugation of former slaves, and they left the elitist governing structures of the old constitutional order intact. They replaced the slaveholder oligarchy with a capitalist oligarchy.

Garrison got one thing right. The whole system is rigged, not just the two-party system. The Constitution was oligarchic from its very inception, not just in its concessions to slavery but in its basic institutional foundation. The only force even conceptually capable of challenging the oligarchy is the fledgling American Left, and that’s why it’s well worth being a part of, no matter what comes to pass. We need an independent party that can move past the cautious legalism of moderate abolitionists and anti-slavery leaders. Instead, we can embrace the militant defense of universal human rights championed by figures like Frederick Douglass and Gerrit Smith. Today, women and minority groups view themselves as inherently entitled to equality regardless of the whims of dead white men—which will make the rhetoric of radical political abolitionism infinitely more compelling.

We can build up an independent party, even if it sometimes lacks legal recognition or engages in major party primaries. We can demand a popular assembly to rewrite the constitution, and set the stage for a new revolutionary crisis in the United States. This time, it will not be North against South. It will be democracy against oligarchy, and the working class majority against the capitalist elites, with socialists as the most relentless and ambitious agitators for freedom. Our road will not be identical—although we may flip the bravest left-wing Democrats, we should not expect a Democratic collapse on anything near the scale of the Whig Party. Even if we obtain massive popular support, we may never achieve the same degree of congressional representation as the early Republicans, and our path to a decisive rupture may rely on a different array of tactics. But if we want a future worth living in, we must begin to envision it: a new birth of independent politics.

What do we have to offer now to the millions who supported Bernie Sanders with dreams of hope and healthcare? To the hundreds of thousands who voted Uncommitted in the face of hideous genocide? For Charles T. Torrey and Tortuguita? All the people who came before us, all the sacrifices they made were in vain, if we don't continue their struggle for freedom. And if slaves and abolitionists could endure odds that seemed hopeless and invent new ways to fight, then who are we to give up?

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 9-10. ↩

- Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2016), 252. ↩

- Ibid, 253. ↩

- Corey Brooks, Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 49. ↩

- Ibid., 49-51 ↩

- Ibid., 51. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Stanley Harrold, American Abolitionism: Its Direct Political Impact from Colonial Times into Reconstruction. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 98. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 49-50. ↩

- Ibid., 53-54. ↩

- Harrold, American Abolitionism, 64. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 61. ↩

- Ibid., 49, 62. ↩

- Ibid., 31. ↩

- Ibid, 33. ↩

- Harrold, American Abolitionism, 95. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 77. ↩

- Ibid., 85. ↩

- Ibid., 18-19. ↩

- Ibid., 19. ↩

- Chase, Salmon P. “The Address of the Southern and Western Liberty Convention: Held at Cincinnati, June 11th and 12th, 1845, to the People of the United States,” p. 10. books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qae6vG6RaGu3kcJ_YC0na8JOMG_8Z9VIZhyHQpfXbvuX3vFCMqfjYiEThTFL0TJWsf5wvfQMmqzd9XQfT7j0OLlwIGcVMO_EHg-RSH7B-fzcK9DUhQnGRpKIngJVxeeo6CxNQUxvrwKqQephaVeFdPjOI-yvK1iBVe7KoPP-2lGUSDBsb8xPvXyjzD4M_YEImZV-AW5qlpRTQOxdDBBxcDSGaMp3RaUwL6BEMMr5Sb3AVhRMmYAeg9RObpltUQ73Oc-Syv1uqWIiUzMIyYb8vHYCsY8KGwlMP1k8p0vdAX7bBgEzczQ ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 77-81. ↩

- Ibid., 90-93. ↩

- Ibid., 81. ↩

- Ibid., 467. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 67-68. ↩

- Harrold, American Abolitionism, 86-87. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 96-97. ↩

- Ibid, 97. ↩

- Ibid, 97-99. ↩

- Liberty Party, Liberty Party Platform, 1844 (San Francisco University High School, US History Documents). https://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter5/libertyparty1844.htm ↩

- Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 58. ↩

- Harrold, American Abolitionism, 71. ↩

- Harrold, Stanley. Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 69-93. ↩

- Sinha, Slave’s Cause, 402. ↩

- Ibid., 233, 403. ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 162. ↩

- Charles Durkee. The Congressional Globe, Volume 21. Blair & Rives, p. 887. ↩

- Douglass, Frederick. “The Fugitive Slave Law” Frederick Douglass’ Paper (1852). Reprinted in the University of Rochester Frederick Douglass Project. https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4385 ↩

- Brooks, Liberty Power, 177. ↩

- Douglass, “The Fugitive Slave Law.” ↩