"I do not think that any self-respecting radical in history would have considered advocating people's rights to get married, join the army, and earn a living as a terribly inspiring revolutionary platform. –Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank, in a 2008 news release"

"I’m a capitalist, and that means I’m for inequality. –Barney Frank, 2006"

I did not hear about Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank (Metropolitan, 2022) until this year, in a Pride month review from Broken Frontier, a sign of how slow comics news can travel. Eric Orner drew and wrote Smahtguy. His work includes comic strip The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, which became a film in 2005. Orner also served as press secretary and staff counsel for one Congressman Barney Frank, so his biography is a biased one. This review will be an attempt to correct some of that bias.

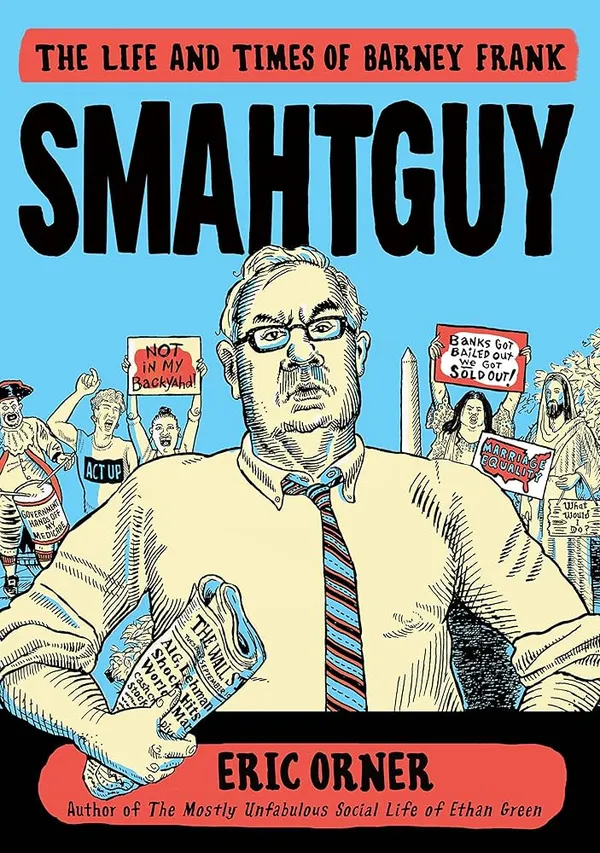

In his Broken Frontier review, Andrew Oliver admits that as a resident of the U.K., he lacks “great depth of knowledge of Frank’s life or wider politics.” Frank represented a rightward-moving American liberalism across the entirety of his career. That liberalism of Smahtguy is apparent from the cover. Frank is in the foreground, while an assortment of activists (A Tea Partier, an Occupy Wall Streeter, and someone from ACT UP) are in the background. Frank is striding purposefully away from them, in a superior position, centered and in the foreground. The cover makes clear that Frank is neither a product of, nor moved by, mass politics.

Barney Frank was born to a Jewish family in Bayonne, New Jersey in 1942. Smahtguy describes Frank’s parents as revering “the liberal icons of the day: FDR, Mayor LaGuardia, Ben-Gurion…”[1] Relevant to current events, Frank followed his parents' example in his steadfast support of Israel. In 2006, he proclaimed that “the Israeli government has been a wholly democratic one from the beginning..It is one of the freest democracies in the world.” Early on, Orner recounts a telling incident from Frank’s upbringing. After his father died, the co-owner of his father’s truck stop refused to sell. Frank then went to some of his dad’s “connected” (i.e. mobbed up) associates to make the man an offer he couldn’t refuse. “It was an early lesson to work the system—any system—to get a desired outcome.”[2] Pragmatism became a defining part of Frank’s political life.

Barney Frank became involved in electoral politics in 1971 as an assistant to Boston mayoral candidate Kevin White. This was a time of transition in LGBTQ+ politics. The earlier gay liberation movement thought revolutionary change was required in US society, epitomized by the Gay Liberation Front. They aligned themselves rhetorically with the Black Panthers and their name was an anti-imperialist provocation given its similarities to the National Liberation Fronts of Algeria and Vietnam. That viewpoint was fading and being replaced by a narrower, civil rights approach, exemplified by groups like the Gay Activists Alliance. No radical, Frank fit comfortably into this second iteration of LGBTQ+ politics.

Frank won election to the Massachusetts State House in 1972 and the U.S. House of Rpresented in 1980. In 1987, Frank became the first Congressperson to voluntarily come out as gay. Two years later, the Unification Church affiliated rag the Washington Times accused Frank of assisting Steve Gobie, a man he had paid for sex, in running an escort service out of Frank’s apartment. Right-wing Republicans jumped on the scandal, hoping to harness a wave of homophobia to expel Frank from the House of Representatives. Congressman William Dannemeyer, an endorser of the LaRouche movement’s multiple attempts to mandate quarantines for people with AIDS, beat the drum loudly for expulsion. Dannemeyer ended his life as a proponent of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and Holocaust denial.

Orner takes numerous shots at Dannemeyer, shown as a hooting, hollering ignoramus, and other icons of the US Right, making the point that many ardent social conservatives were hypocrites. Newt Gingrich and Larry Craig called for Frank to be expelled, even though both of them would leave office under a cloud of sexual scandal. Pat Buchanan is caricatured wearing the Nazi uniform he has done so much in his life to earn. Showcasing the US Right reminds readers how dire things were for LGBTQ+ rights in the recent past. It also puts lie to the claims by liberals and moderates that there was once a “kinder, gentler” Republican Party worth mourning. On LGBTQ+ rights, as well as many other issues, they were bad yesterday, they are bad today, and they’ll be bad tomorrow.

But, Orner’s book also evinces a great deal of hostility towards anyone to the left of Frank. Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold, nicknamed in the text “Russ Feingoldeanus,” is mocked for his “virginity” because he was too “pure” to vote for the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act since the proposal wasn’t tough enough on big banks. Frank’s thought balloon shows a bloody dagger as the Congressman reaches towards a pen.[3] This derision is so great that Orner warps chronology to get in a dig at former Congressman Dennis Kucinich. Kucinich is described as “having run for President on a platform stressing belief in UFOs” in the 1990s. Capitol policemen snicker, “How’s them aliens?”[4] Of course, Kucinich actually ran for President in 2004 and 2008. He didn’t even enter Congress until 1997.

By contrast, President Bill Clinton is treated with much more sympathy in Smahtguy. Clinton’s presidency is described by the narrator as a “progressive presidency (albeit one headed by a flawed president).” Frank says, “the most successful Democratic administration since FDR.”[5] Orner is well aware of Clinton’s backsliding on queer rights. He shows how the President, “in his exasperating and split-the-difference way,” signed the homophobic Defense of Marriage Act declaring marriage was reserved for one man and one woman.[6] In 1996, the President’s campaign ran ads on Christian radio stations touting his support for the law. Clinton also signed the law introducing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, the policy that allowed LGBTQ+ people to serve in the military solely as long as they were in the closet. In Smahtguy, Barney Frank is credited (or blamed?) for giving Clinton the idea of the compromise that became Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.[7] In a 2015 article, Frank assessed Clinton not “as an enemy who held out false promise but as a friend who had tried to help us and failed.”

Clinton’s presidency was a failure for all but a select few. Clinton himself succeeded, as he was reelected twice. But, his own Democratic party suffered. Clinton failed to bring down-ballot Democratic candidates along with him in victory, meaning that the party was out of power in Congress for most of his presidency. The real victims of Clintonism were Black people, the poor, gays and lesbians, and organized labor. Under Clinton, Black people received the 1994 Clinton Crime Bill that supercharged mass incarceration. Those incarcerated as a result of the Bill are disproportionately Black. The poor got a welfare reform bill that Hugh Price of the Urban League called “an abomination for America’s most vulnerable mothers and children.” When the program was created, 68% of poor families received cash assistance. By 2020, that number had dropped to just 21%. Clinton’s signature economic policy, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), led to a loss of nearly 700,000 jobs, a majority of them in unionized manufacturing.

At the time, Frank was aware of how awful many of these policies were. He voted against NAFTA, welfare reform, and the Defense of Marriage Act. The Congressman also voted against consequential pieces of Clintonian deregulation like the 1996 Telecommunications Act and the 1999 Financial Services Modernization Act that removed regulations for much of the banking industry. He did vote for the crime bill, however. It’s clear that, at the time, Frank viewed many of the landmark bills proposed by Clinton negatively. Yet by some strange alchemy, a President who pushed for and signed so many bad bills is judged a success by Orner and Frank.

The Democratic Party took control of Congress in 2007. Frank assumed chair of the House Financial Services Committee, the committee that oversees banking and finance. Before he took his seat, Frank proposed a “grand bargain” between the incoming Democrats and US corporations: Democrats would agree to support free trade agreements without labor and environmental protections in exchange for an increase in the minimum wage and card-check legislation that would make it easier for workers to unionize. No such bargain ever materialized. The fact that Frank would propose such a thing even while Democrats controlled Congress is a revealing display of how much he valued “pragmatism,” or what might be termed less charitably, “selling out.” Frank thought it was necessary, even desirable, to cut deals with the other side, even when Democrats were in a majority. In an interview with the Comics Beat, Orner said Frank “never believed in leaving three quarters of a loaf on the table, just because at a certain point in time there was no way of getting the whole loaf. He didn’t believe in letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

His tenure as chair and his efforts to rescue the US economy are the climax of Smahtguy. A large part of this was the $700 billion bailout of failing banks. The bailout is presented as a “take it or leave it” proposition. Either a politician wants to rescue the economy or not. There’s no allowance for alternative proposals like nationalizing those failed financial institutions. Indeed, the United States government could have purchased them with the amount of money it put up. Today most of those banks are larger than they were before the US government bailed them out. This means that in the event of another financial crisis, these institutions, considered “Too Big to Fail” would again be bailed out at taxpayer expense. Frank is shown working very closely with President George W. Bush’s treasury secretary Hank Paulson to shepherd the bailout through Congress. When anti-bailout Democrat Brad Sherman tagged Paulson as “Bush without the hair,” Frank cussed him out.

Frank’s key legislative accomplishment was the aforementioned Dodd-Frank Bill. This bill did not shrink the largest banks and was criticized at the time by business analyst Doug Henwood for not doing enough to protect consumers from bank failures.

“It would be an exaggeration to call it nothing, but it would also be an exaggeration to call it a major transformation of the financial landscape...bankers headed off the biggest threats, and security analysts estimate that the hit to profits will be less than 10%...One point: the capital requirements mandated (capital in this sense meaning a wad of hard cash that isn’t borrowed and therefore is free to tap into in a crisis) in this bill are in the range possessed by Lehman Bros. before it went under. So clearly that’s not much of a guarantee of anything.”-Doug Henwood

Smahtguy portrays Frank as accomplishing a Herculean task in passing Dodd-Frank, and valorizes him for doing so. The truth is that Dodd-Frank was a band-aid solution that did nothing to solve the underlying problems of large financial institutions. It did not even go as far as the New Deal era’s Glass-Steagall legislation that broke up the big banks and mandated a separation between commercial and investment banks. Dodd-Frank is held up as a heroic piece of legislation, even though it marks a retreat from the Democratic Party horizons of the 1930s.

Notable by their absence in Smahtguy are Frank’s positions on a number of gay issues, barring Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and the Defense of Marriage Act. Despite the presence of an ACT UP protester on the cover, there’s nothing about the battles over AIDS funding. Looking at Frank’s stances on these issues, it becomes clear why they are not included. Simply put, they would make Frank look bad. When then-San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, Frank dismissively called the weddings a “symbolic point.” Ironically, one of the couples Newsom married, Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, were founders of the Daughters of Bilitis, the lesbian rights organization that endorsed Frank in his first run for state house.[8]

There is also no discussion of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, which would bar employment discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. In 2007, Frank and liberal stalwart Senator Ted Kennedy introduced a version of the act that excluded transgender people from protection. Frank described this version as a “compromise” but admitted it would leave a “gap” by not covering trans people. Almost every LGBTQ+ rights group in the U.S., including the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and Pride at Work, opposed this attempt to throw trans people under the bus in an attempt to win over Republicans and conservative Democrats. Frank blamed trans people themselves for failing at lobbying effectively to get trans rights in the bill in a 2014 interview: “instead of trying to put pressure on the people who were against them, [trans rights advocates] thought they could just insist that we do it.”

2009’s National Equality March was an effort by LGBTQ+ protesters to urge President Obama to keep his campaign promises to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and pass the Matthew Sheppard Hate Crimes Act. They didn’t want the newly elected president to cut his conscience to fit that year’s fashions. Frank prognosticated, “[t]he only thing they’re going to be putting pressure on is the grass.” He would have preferred marchers stay home and write to their members of Congress. Sherry Wolf, a march organizer, reported that student protesters chanted “Barney Frank, fuck you!” in response.

When Frank retired from Congress in 2013, there were a host of pieces in lefty outlets like The Progressive and In These Times lamenting his exit from the House. Frank’s retirement from Congress and his marriage to his partner Jim Ready provide Smahtguy’s requisite happy ending. Of course, leaving Congress did not mean Frank left public life. That Orner ends his book where he does is meant to present an image of Frank that he wants readers to come away with, even if it does not tell the full story. Orner’s Frank is the acceptable boundary of left thought and action in the US. To go beyond him is to invite ridicule and failure.

Smahtguy ends before Frank assumed the identity that I came to know him by: that of public scold. During the 2016 Democratic Primary, Frank was an attack dog for the Clinton campaign, focusing most of his attention on Bernie Sanders. Frank as an ideological policeman wasn’t new. In 2000, he flew to Madison to encourage Wisconsinites to reject Ralph Nader. Al Gore, Frank’s preferred candidate, had called gay people “abnormal” during his first run for the U.S. Senate. Four years later, Frank viewed it as a positive mark for John Kerry that he didn’t need Frank to “calm down the left” and keep them from voting Nader. He said at the time, “Kerry has less of a problem on the left than any candidate in my memory.”

In 2016, Frank spoke of Sanders supporters like this: “[y]ou have people, I believe, who do not understand how hard it is to make change, the importance of not just being idealistic, but being sensibly pragmatic and keeping their ideals.” Presumably, he included himself and Hillary Clinton among those who are sensibly pragmatic but have kept their ideals. Frank termed complaints about Clinton’s closeness to Wall Street, seen in the amount of money she raised from big banks, “McCarthyism of the Left.” He concluded, “there is no evidence that they have had any influence on her policies, which are as tough as anyone’s.” Pragmatism meant endorsing the “electable” Clintons, Kerry, and Gore, without reservations thereby giving a liberal gloss to what were the most conservative Democratic campaigns.

Isaac Chotiner interviewed Frank that year for Slate. He continued to pour scorn on Sanders and his supporters: “I’m particularly unimpressed with people who sat out the Congressional elections of 2010 and 2014 and then are angry at Democrats because we haven’t been able to produce public policies they like…They contributed to the public policy problems and now they are blaming other people for their own failure to vote, and then it’s like, ‘Oh look at this terrible system,’ but it was their voting behavior that brought it about.” It never occurred to Frank that many of the young leftists supporting Sanders could not vote in either 2014 or 2010.

Frank was not a New Democrat like Bill Clinton, Al Gore, or Joe Biden who sought to remove any influence from labor, civil rights groups, or peace activists inside the Democratic Party. Instead, the New Democrats wanted financial support from large corporations and the rich and political support from conservative “Reagan Democrats.” Frank was never included in this group; he maintained his membership in the Congressional Progressive Caucus, the left-leaning bloc in the U.S. Congress. Nevertheless, he, as demonstrated, spent much of his time campaigning for candidates who opposed the stated goals of the Progressive Caucus and excusing them of their faults all the while they shifted the Democrats and the U.S. further to the right. Fran’s purpose was to provide these politicians with a degree of left cover as they did so.

In addition to his role policing the left flank of the Democratic Party, Frank has also played a notable role in the debate over his signature piece of legislation, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act. As soon as the ink dried on the bill, banks and their hirelings in office have worked to weaken, if not overturn, the law. Once Donald Trump assumed office in 2017, these corporate flunkies saw their chance and passed a bill significantly weakening Dodd-Frank. Was Barney Frank concerned? Numerous media outlets quoted him as saying that weakening the rules wasn’t a big deal. “It does not in any way weaken the regulations we put in there for the largest banks,” Frank said, “or that were there to prevent the kind of crisis we had ten years ago.” Many of the outlets that quoted Frank failed to report on his new career: board member of New York-based Signature Bank.

Signature benefited directly by amending parts of the law, as they were about to reach the $50 billion threshold in assets that required mandatory “stress tests” from regulators. After the stress tests were repealed, Signature Bank became a casualty of the third-largest bank failure in US history in 2023, when investors worried over the failure of Silicon Valley Bank withdrew $10 billion in cash. If the capital requirements in Dodd-Frank had not been repealed, it’s likely both banks would not have failed. Instead, Signature was taken into federal receivership.

Although Orner fails to address this other side of Frank’s life, he is obviously a skilled cartoonist. He packs every page with detail and most pages have at least seven panels of story. He uses colors that may not be natural looking (sunshiney yellows, salmon pinks, bright blues) but together they are a visually pleasing palate. His sense of humor works more often than not, and I chuckled more than once. Orner has talent, despite my deep political disagreements.

In an interview with the Washington Blade, Orner explained that he “didn’t want to do hagiography.” Smahtguy doesn’t fall into that category, but it is extremely protective of its subject, certainly due to Orner’s twenty-odd years of working for Frank. The version of Frank presented is meant to be a guide to today’s activists. They should work within the Democratic Party, compromise with the establishment, and generally not seek to rock the boat. In short, they should be like Barney Frank. Kirkus’s review ends, “those who don’t realize the extent of his political legacy will learn much.”

Indeed, there is much to learn from Frank’s political life, but much of it is what not to do. How he has ended up lobbying against his own piece of consumer protection legislation is a sad commentary on the revolving door between political office and corporate America. Frank’s promotion of compromise for its own sake, his habitually punching left, and his willingness to sacrifice legal protections for trans people in exchange for perceived political advantage are all things to be avoided. Today’s movements to end inequality and oppression must have a more militant, radical vision than Barney Frank’s if they are to succeed.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.