When I visited the Motown Museum last, in the Fall of 2015, I was surprised by how small it was. It seemed to me that the place that produced so many songs indelibly etched into my mind should have been grander. As it is, the Museum is two middle class houses that have been cobbled together to form a continuous structure. During my visit I noticed a profound sense of nostalgia, both on the part of the museum itself, as well as on the part of my fellow guests, for the Detroit of the 1960s and 70s. That “Golden Age” of Detroit is inseparable from the history of Motown. By studying Motown, much can be learned about the politics and history of Detroit, particularly if attention is paid to the label’s artist’s changes in music and political expression over the years.

Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. was born in Detroit in 1929 to parents who emigrated to the city in 1922 seeking job opportunities. After spending time as a professional boxer, at one point fighting on the same card as Joe Louis, and serving in the Korean War, Gordy found work at Ford Mercury earning $85 a week. He found factory work monotonous and boring, and spent all his free time writing songs, so in 1959 he borrowed $800 from his family to start his first record label, Tamla. The Motown Corporation was founded five months later. Under the Motown umbrella, Berry Gordy introduced the world to such acts as Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Supremes, the Temptations, Martha and the Vandellas, the Jackson 5, and many more. The labels under Gordy’s ownership were veritable hit machines, dominating the pop charts with 63 number one hits from 1961 to 1973 and producing the self-proclaimed “Sound of Young America.”

Motown, Detroit, and the US Auto Industry

The houses that comprise the museum are a view into the living conditions of post-WWII Detroit during the "Golden Age of Capitalism.” They are comfortable middle-class homes of two stories with a basement, indicating that Detroit was home to a thriving Black middle-class during this period. At that point in time, manufacturing, particularly in the auto industry, sustained 400,000 jobs, most of them with union wages and benefits, within the city.[1] This was the economic bedrock that allowed Gordy to start his own record company.

The auto industry is further connected to Motown through the record label’s assembly line-like production process and rigorous commitment to quality control. Every song had to be approved at multiple levels before it could be released. Motown artists were taken into the Artist Development Department (or Motown Finishing School) and given classes on choreography, etiquette, and stage presence. Artists were also not permitted to write their own material, this was to be handled either by producers or songwriters like Norman Whitfield or the team of Holland-Dozier-Holland.[2] Gordy himself wrote in his autobiography that his approach was “shaped by the principles [he] had learned on the Lincoln-Mercury assembly line.”[3]

Motown’s connection to cars doesn’t end just at the level of simile. Motown recordings were often played through car speakers in the studio to see what would sound best on future listener’s own radios. Publicity photos of Motown talent like Marvin Gaye often included Cadillacs or other US-made cars, thereby associating two popular Detroit products at the same time. Martha and the Vandellas participated in a national CBS broadcast in which they performed “Nowhere to Run” on the Mustang assembly line at the Ford River Rouge Plant, combining both “the Car of Young America” with “the Sound of Young America.”[4]

Motown and the Civil Rights Movement

Motown is commonly associated with the contemporary Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, but Motown’s relationship to the movement is complicated. Motown did attempt to portray a positive, uplifting version of Black society and it released a recording of Dr. King’s speech from the 1963 Great Freedom March in Detroit. Additionally, Berry Gordy was given honor by the National Council for Christians and Jews during its annual Brotherhood Week.[5] However, there was resistance, at first, to releasing songs that carried messages of social protest on the part of Gordy. Early Motown was characterized by songs such as the Contour’s “Do You Love Me?” and the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman.” These were apolitical upbeat numbers about romance, not revolutionary change. Otis Williams of the Temptations said that part of Motown’s finishing school was instructing artists to shy away from controversial topics. Musical director Maurice King “would tell [artists] ‘Do not get caught up in telling people about politics, religion, how to spend money, or who to make love to, because you’ll lose your fanbase.’”[6]

This did not stop some activists and critics from claiming that these early Motown songs carried hidden political messages. For example, Martha and the Vandellas’ 1965 hit “Dancing in the Streets” was said to be about the Civil Rights movement or 60s urban riots, even though there was no conscious political intent to the song. Similarly, Junior Walker and the All-Stars “Shotgun” was associated with the assassination of Malcolm X as well as the 1965 Watts Uprising due to its lyrical content and the sound of a shotgun blast opening the song. These associations were aided by the travails of Motown’s performers. When the original Motortown Revue, a roadshow of Motown artists, left Detroit to tour the South in Fall 1962, they faced segregated facilities and were even shot at, much like the Freedom Riders the previous year who had attempted to use nonviolent protest to desegregate public transportation.[7] If performers weren’t interested in politics, politics was certainly interested in them.

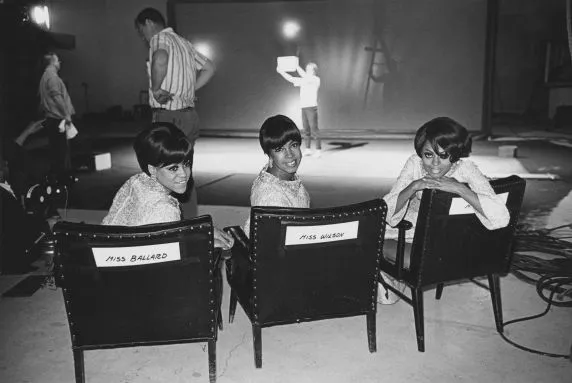

After the tumultuous 1967 Detroit Uprising, the assassination of Martin Luther King, and in the context of a growing Black Power movement, Motown became more overtly and intentionally political. Berry Gordy was convinced by three of his Los Angeles staffers that his company had an obligation to popularize the spoken voice of Black America. As such, Motown launched the imprint Black Forum in 1970, which released spoken word recordings from Black leaders like Martin Luther King, Langston Hughes, and Stokely Carmichael. This represented a real concession on Gordy’s part, since none of Black Forum’s recordings were strong sellers. In the aftermath of the Detroit Uprising, Motown artists performed for Detroit Is Happening, a job creation and educational plan meant to discourage future violence. Stars Stevie Wonder, the Supremes, and the Temptations performed at an Atlanta benefit for the Southern Christian Leadership Council’s Poor People’s Campaign.[8] Explicitly political music, however, was still lacking.

The MC5, a white Detroit rock group that pioneered the template of punk, was far ahead of any Motown artist in terms of politicizing their art. As part of their anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist activism, the band played a free show for anti-Vietnam War protesters at the infamous 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention, though they had to play on a flatbed truck due to the mayor’s denial of permits for a stage. Novelist Norman Mailer described their show as “an interplanetary, then intergalactic, flight of song.”[9] Russ Gibb, writing in Detroit’s underground newspaper the Fifth Estate, prognosticated “the next Big Sound is gonna be the Detroit Sound…and I don’t mean Motown, mofo…” so obvious was Motown’s seeming lack of relevance to the social movements of the 60s.

Motown Turns to Protest

Perhaps sensing this feeling, in 1970, Motown Records finally started to release protest songs. Edwin Star was given the anti-war song “War” to record as a single after it was deemed too controversial for the Temptations, the song’s original performers, to release in single form. The Temptations would bemoan war, racism, and drug abuse on “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today).” Norman Whitfield, songwriter behind both songs, didn’t think much of their political content. When an interviewer asked about messages in his oeuvre, Whitfield responded “They got Western Union for that.”[10] Nor did every Motown artist make an effort to speak out. When the Jackson 5 were asked about political issues during a television interview, a handler stepped in to say that as a “commercial product” the group wouldn’t comment on controversial topics.[11]

In 1971, Marvin Gaye released a whole protest album with What’s Going On, addressing issues like poverty, ecology, and the Vietnam War. Gaye recalled that he was listening to “Pretty Little Baby,” a hit of his, on the radio when the Watts Riots were announced. “I wanted to throw the radio down and burn all the bullshit songs I’d been singing,” Gaye said, “and get out there and kick ass with the rest of the brothers… Why didn’t our music have anything to do with this?”[12]

What’s Going On was Gaye’s attempt to make music that had something to do with the spirit of the times. But the album faced push back from Gordy. When Gaye announced he was making a protest album, Gordy responded “Protest about what?”[13] The Motown head felt the album was not commercial enough; he allegedly called the title track “the worst thing I’ve ever heard in my life.” Gaye went on a one-man strike, refusing to work unless Gordy changed his mind about the track.[14]

The 1967 Uprising also did unintentional harm to the 1967 promotional film It’s Happening, which featured the Supremes. The film was made as part of the United Foundation’s Charity Torch Drive, which began in 1965 with support from prominent businessmen and politicians. The film spotlights how charitable giving through the fund helped disabled children, the blind, stroke victims, and others with narration from Diana Ross. The Torch Drive Campaign, due to the recent Uprising, specifically declined to show the film in the white suburbs of Detroit, because it was felt that the white suburban audience harbored “considerable resentment” towards the inner-city Black community represented by the Supremes.[15]

That “considerable resentment” was given organizational form by Breakthrough, a racist, anti-Communist group led by Donald Lobsinger. Although described by the Fifth Estate as a bunch of “uptight honkies,” the group prepared for violence. Lobsinger wanted whites to arm themselves due to fears that if Detroit “became black” it would result in “guerrilla warfare in the suburbs.”[16] Detroit’s Black newspaper, the Inner City Voice reported that a Breakthrough meeting urged its audience to hoard guns and ammunition to defend against “those people” from Detroit. The paper further reported that Lobsinger warned a Wayne State University audience that “we [white Detroiters] have guns and will use them, if you Communists insist on resorting to violence.” The organization protested Martin Luther King’s 1968 appearance in the tony suburb Grosse Pointe with signs reading “King is a traitor” and “Burn traitors, not flags.”

The socialist Left had its own troubled relationship with Motown. Franklin Rosemont, for the Rebel Worker, was positive. He felt that artists like “Martha and the Vandellas, Marvin Gaye, The Jewels, The Velvelettes, The Supremes, and [and] Mary Well” showed the new generation’s “refusal to submit to routinized, bureaucratic pressures.” For the Workers League (predecessor to today’s Socialist Equality Party—talk about uptight honkies!), member Marty Jonas argued that while Motown songs “very often express feelings of real love and contact with society… as the Supremes’ disappointing ‘Reflections’ shows, this fine heritage can go under to the psychedelic influence.” Over at the Inner City Voice, by now an organ of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, an anonymous writer rewrote the lyrics to “Ball of Confusion” into a call for revolutionary action. This shows that while radicals were well aware of Motown, some did not view its lyrics as speaking for them. After all, no Motown song would contain the lyrics “And the only way to cure all these ills/Is the Black revolution!” The League also worried about the appeal of “'Cloud Nineism' (escapism through drugs),” an allusion to the psychedelic soul tune “Cloud Nine” by the Temptations.

The Contradictions of Motown

There were signs in the late 60s that Motown was planning a move from Detroit to Los Angeles, given that the Jackson 5 exclusively recorded in California after originally auditioning in Detroit. Eddie Willis, of legendary Motown backing band the Funk Brothers was still caught by surprise. “One day we went to the studio and we were supposed to record,” he remembered, “There was a big sign on the door saying there won’t be any work here today—Motown’s movin’ to Los Angeles.”[17]

Even so, the move served as another blow to Detroit as a center for innovation in popular music. Already the Stooges, as well as the aforementioned MC5, who were promoted by critics like Lester Bangs of Creem as the saviors of rock music, had collapsed due to issues with drugs and lack of commercial success.[18]

Motown’s decision to leave also mirrored those of the auto industry to relocate to more advantageous locations outside of the “Motor City.” In the end, Hitsville USA behaved like any other capitalist concern. If the company wanted to expand into television and film production, moving to Los Angeles made perfect economic sense. Nevertheless, even though the company had success in this field with films like Lady Sings the Blues or the cult kung fu film Barry Gordy’s the Last Dragon, it was never at the same cultural or commercial level as their earlier Detroit-based output.

The Motown story is one of contradictions between commercial interests and artistic expression, as well as different approaches to political involvement. Shrewd capitalist that he was, Gordy was always more concerned with having a successful business than making political art. It was only after shifts represented by the activity of artists like Marvin Gaye that the label released more explicitly political songs, including later recordings by Stevie Wonder. This growing interest in politics also coincided with artists' growing desire to write their own songs and have a creative voice that went against the company’s earlier attempt to standardize its product.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Scott Martelle, Detroit: A Biography (Chicago Review Press, 2012), 213.

↩ -

Gerald Early, One Nation Under a Groove: Motown and American Culture (University of Michigan Press, 2004), 54.

↩ -

Berry Gordy, To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown (Headline, 1994), 140.

↩ -

Suzanne E. Smith, Dancing In the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit (Harvard University Press, 1999), 123-127.

↩ -

Ibid, 17, 136-137.

↩ -

Dorian Lynskey, 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, From Billie Holiday to Green Day (HarperCollins, 2011), 144.

↩ -

Early, 104.

↩ -

Lynskey, 148-149.

↩ -

David Carrson, Grit, Noise, and Revolution: The Birth of Detroit Rock ‘n’ Roll (University of Michigan Press, 2005), 170-173.

↩ -

Ben Edmonds, What’s Going On? Marvin Gaye and the Last Days of the Motown Sound (MOJO Books, 2002), 211.

↩ -

Smith, 229.

↩ -

David Ritz, Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye (Da Capo Press, 1985), 107.

↩ -

Gordy, 302.

↩ -

Lynskey, 157.

↩ -

Smith, 184-189.

↩ -

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (University of Michigan Press, 1989), 383.

↩ -

Carson, 277.

↩ -

The Stooges would reunite in 1973 at the behest of David Bowie to little commercial effect.

↩