Bushcraft refers to the ability to survive and adapt in the wilderness by utilizing both modern and traditional techniques. Engaging in bushcraft involves skills such as fire-making, navigation, tracking, and building shelters using available tools and materials.[1] More than just survival, bushcraft emphasizes long-term self-sufficiency and comfort in nature. It fosters a deep connection with the environment, ensuring sustainable resource use and minimizing ecological impact. Interestingly, modern society's detachment from nature has contributed to the growing appeal of bushcraft and forest-related activities. Essential aspects include securing clean water, warmth, shelter, and food. Mastery of various skills—such as stone tool crafting, fire-starting, foraging, hunting, fishing, constructing shelters, making rope and cordage, processing animal hides, tracking, navigation, and weaving—is crucial for practicing bushcraft effectively.[2] Bushcraft is also directly related to the movement called "survivalism."

Survivalism refers to the practice of preparing for the catastrophic collapse of society. Also known as "prepping," it involves readiness for various crises, including ecological disasters, economic breakdowns, civil conflicts, nuclear warfare, and foreign invasions.[3] Deeply intertwined with eschatological anxieties, survivalism relies heavily on bushcraft skills. Social media hosts enormous amounts of content demonstrating these techniques.[4] Survivalism also reflects deep class inequalities. Among the super-rich, it is common to invest in luxury bunkers repurposed from Cold War-era nuclear missile silos, ensuring their survival in the event of ecological collapse or a doomsday scenario that threatens the existing social order. This elite form of survivalism, often dismissed as a whim of a few eccentric billionaires, is far from an isolated phenomenon. As Evan Osnos documented in The New Yorker in 2017, the idea of “apocalypse preparedness” has been rapidly spreading among the wealthy, reinforcing existing disparities in access to safety and resources.[5]

Christian Eschatology, Crypto-Fascism, and Survivalism as Right-Wing Utopia

The evolution of the techno-cultural sphere is deeply intertwined with broader social dynamics. The growing popularity of survival videos should be understood within this context. However, survival videos are not a novel phenomenon. They are rooted in the concept of preparation, which historically draws from Christian eschatology’s notion of anticipating the end of the world. Right-wing ideologies have adapted this idea, blending it with utopian elements. Utopia, as a vision of an ideal future, shapes civilizations by guiding their aspirations and structuring their goals.[6] Within this framework, apocalyptic narratives serve as a mechanism of ideological rebirth for the right wing, offering a renewed sense of purpose and filling the void left by shattered hopes.[7] This right-wing utopia ultimately envisions a "liberated" future.[8]

Survival videos often carry an alarmist undertone, amplifying concerns about various crises, including ecological disasters, natural calamities, and immigration. This alarmism aligns with right-wing populist strategies, which thrive on narratives of crisis and emergency.[9] Right-wing populism, however, shares an intrinsic connection with fascism, though overt fascist rhetoric remains absent in these videos. Fascism, as a historically recurring socio-political pathology, disguises itself within ideological structures, adapting to different temporal and spatial contexts. Crypto-fascism, in particular, operates through linguistic ambiguity, allowing fascist ideologies to subtly permeate discourse. It often manifests as an early signal of more explicit fascist expressions, drawing on coded language and symbols to normalize extremist ideas.[10] Instances of crypto-fascism can be observed in groups such as the Freedom Party of Austria and the German Republicans.[11]

As a communicative strategy, crypto-fascism employs a range of rhetorical and symbolic tactics to advance its ideological objectives. These include outright denial, euphemism, selective pedanticism, concealed symbolism, solidarity among offenders, humor and satire, deflection, and appeals to free speech as a shield against critique.[12] In this sense, survival videos exhibit a crypto-fascist agenda through the stereotypes they reinforce and the binary oppositions they construct. By framing a moral dichotomy of good versus evil, they position immigrants as the threatening "other," fueling exclusionary narratives that align with broader right-wing extremist ideologies.

However, this study discusses whether this apocalyptic narrative can be saved from the hands of right-wing ideologies, due to the current climate crisis—and even its collapse, according to some. Here, Walter Benjamin's unique concept of revolutionary pessimism provides a way of assessing if leftists can reorient these contemporary understandings of collapse. His unique form of revolutionary pessimism, as described in his 1929 essay on surrealism, reveals his attempt to reconcile anarchism and Marxism. For Benjamin, pessimism was not a form of resignation but a necessity for organizing radical transformation. This perspective is crucial in understanding survivalism’s ideological undercurrents. While survivalist narratives present themselves as pragmatic and apolitical, their alarmist tone and fixation on crisis reinforce reactionary structures rather than fostering revolutionary change. Benjamin's critique of progress as an illusion dismantles survivalism’s implicit assumption that crisis will lead to renewal. Instead, he urges us to see history not as linear advancement but as moments of rupture where revolutionary potential exists.

Benjamin’s Revolutionary Pessimism and the Critique of Crisis-Based Renewal

Benjamin critiques the idealization of industrial labor to free Marxism from progressivist illusions. This is relevant in analyzing survivalism’s glorification of pre-industrial skills and individual resilience as a response to systemic collapse. He would likely see this not as an escape from capitalism, but as a reactionary retreat that ignores structural crises. Just as he warned against the aestheticization of labor, he might critique survivalism’s romanticization of hardship as self-actualization rather than resistance to exploitation. His reluctance to formally align with any political party reflects his libertarian Marxist approach, resisting rigid frameworks and favoring a synthesis of anarchist insurrection and revolutionary discipline. This helps expose survivalism’s contradictions—while it claims to seek autonomy from state control, it often aligns with authoritarian right-wing narratives.

Benjamin’s perspective forces us to ask whether survivalism resists oppression or merely reinforces reactionary tendencies under the guise of self-reliance. His lifelong effort to fuse anarchism with Marxism also sheds light on survivalism’s ideological position. He would likely critique its failure to recognize systemic power structures, much like he questioned Marxism’s naive faith in industrial progress. Survivalism presents itself as resistance, but resistance against what? Benjamin’s engagement with surrealism further informs this critique. He saw surrealism as reviving radical freedom, pushing it toward communism due to bourgeois hostility. Survivalism, however, rejects modern society through reactionary isolation rather than revolutionary transformation. Benjamin’s thought compels us to question whether survivalist preparedness is truly liberatory or merely bourgeois paranoia disguised as autonomy.[13]

Unlike Marx, who saw revolutions as the locomotives of history, Benjamin viewed them as the emergency brakes that could halt history’s relentless trajectory toward catastrophe. For Benjamin, Marx’s metaphor remained trapped within the mythology of progress, where railroads—symbols of industrial society, power, and speed—had dominated the 19th-century imagination. Benjamin, however, sought to break with this deterministic view by positioning interruption not only as the essence of revolutionary politics but also as the fundamental principle of political action itself.[14] Interruption, or the shattering of historical continuity, is deeply tied to concepts of progress, historical opportunity, and the possibility of transformation. However, Benjamin’s understanding of revolution rejects the notion of mature revolutionary conditions. Instead, he envisions a permanent revolutionary orientation that actively seizes history rather than passively awaiting its teleological development. This act of appropriating history does more than redirect its course; it dismantles the foundational premise of progress by extracting suppressed hopes from the past. Benjamin challenges the assumption that history is a linear ascent toward justice and happiness. Instead, he argues that the past is not an inferior stage of the present but a hidden reservoir containing both traumatic and utopian moments, waiting to be reclaimed.[15]

Benjamin’s emphasis on the state of exception challenges conventional understandings of history and progress. In The Arcades Project, Benjamin argues that the past carries an ember of hope that can only be ignited by those who truly absorb history. He warns that if the oppressor triumphs, even the dead will remain in the grasp of domination, as the victors continue to write history in their favor. This critique resonates deeply with his rejection of historicism—where history is told from the perspective of the winners, continuously legitimizing existing power structures. Benjamin asserts that every victory has marched over the defeated, reinforcing the rule of those in power. Identifying with the victors perpetuates the cycle of oppression, making it imperative to adopt a historical perspective that centers the tradition of the oppressed. According to Benjamin, what is perceived as a state of exception—moments of crisis, repression, or rupture—is, in reality, the norm under capitalist modernity. Recognizing this allows for a radical rethinking of history that moves beyond progressivist illusions.[16]

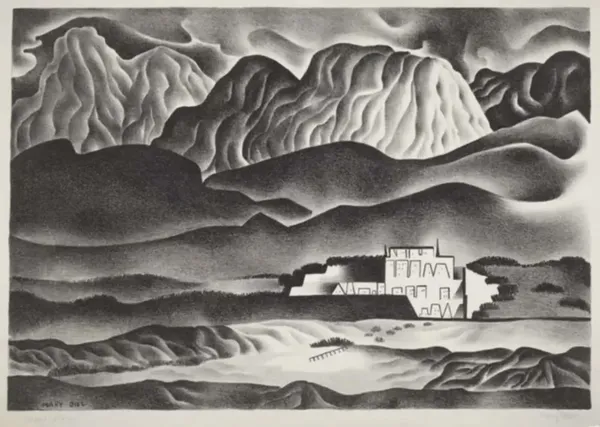

His apocalyptic vision is encapsulated in the “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” particularly through the metaphor of the Angel of History. Inspired by Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, Benjamin describes an angel looking back at history, witnessing an ever-growing pile of wreckage. The angel wishes to stop and repair the destruction, but a storm, which Benjamin equates with the notion of progress, propels it forward, preventing any intervention. Benjamin sees revolution as a disruption of the continuous march toward catastrophe, an obstacle rather than an engine. His historical materialism rejects the teleological assumption that history inevitably leads to justice, instead emphasizing rupture—a break from the myth of progress. Benjamin argues that history is written by the victors, suppressing the voices of the oppressed. His apocalyptic imagery serves to expose this illusion, urging a different historical consciousness that recalls forgotten struggles and buried utopias. The Angel of History, therefore, embodies both despair and hope—the recognition of relentless destruction and the ever-present potential for redemption through revolutionary action.[17]

In Benjamin’s theological framework, apocalypse is not merely an end, but also a beginning. His analysis of Trauerspiel in The Origin of German Tragic Drama presents history as an unending cycle of transience and decay,[17] where there is no final redemption or resolution. This perpetual decline prevents radical transformation while stripping history of permanence, creating a vision of time dominated by nature’s endless rule, experienced as ceaseless torment. In these bloody dramas, the most accomplished creations are closest to ruin, and humanity, as fallen beings, becomes an imperfect reflection of a world lacking transcendence. History, absorbed into nature, takes the form of perpetual struggle, where power conflicts persist but fail to produce lasting change. Rather than a linear progression or an ultimate reckoning, history eddies in a vast and chaotic space, trapped in a state of incessant decline. The Trauerspiel negates the idea that historical struggles yield meaningful achievements, revealing instead a cycle of loss and dissolution. Yet, despite this bleak vision, Benjamin still leaves room for rupture—a moment of interruption that could break the relentless momentum of destruction and create the possibility for new beginnings.[18]

The Possibility of a Left-Wing Collapsology

Today we can theoretically adapt Benjamin's ideas through "collapsology." Collapsology, as discussed in “The Splendor and Squalor of Collapsology,”[19] is a theoretical framework that examines the potential collapse of industrial civilization due to environmental crises, resource depletion, and systemic failures. It argues that modern societies are on an unsustainable trajectory, necessitating a shift toward resilience and adaptation rather than attempting to prevent collapse altogether. While rooted in scientific analyses, it incorporates elements of grief psychology and millenarian thought, framing societal decline as both a catastrophe and an opportunity for renewal. However, critics argue that collapsology is fatalistic and apolitical, presenting collapse as an inevitable fate rather than a preventable crisis, thereby discouraging political action. It also risks reinforcing social inequalities by implying that those with access to land, resources, and self-sufficiency will be best positioned to survive, ultimately benefiting the privileged while neglecting systemic injustices. Although collapsology highlights the fragility of industrial civilization, its emphasis on adaptation over resistance suggests a passive acceptance of disaster rather than an active engagement in systemic change.[20]

Collapsology, despite its often fatalistic outlook, can also be re-positioned as a left-oriented movement that seeks to prevent pessimism from devolving into apolitical resignation. As an emerging field, collapsology directly engages with the intersectionality of multiple crises, including climate change, biodiversity loss, social inequalities, technological disruptions, and pandemics. The widespread belief in an impending civilizational collapse, particularly in countries like France and Italy where a majority anticipate a significant decline within the next two decades, reflects a broader cultural mood of anxiety and disillusionment. This pessimistic sentiment is not just captured in surveys but also in contemporary media, from documentaries like Life After People to dystopian narratives such as “Fear the Walking Dead,” which resonate with public fears about the fragility of modern civilization. However, collapsology need not be a passive acceptance of catastrophe. It holds potential as a politically-engaged critique of industrial capitalism’s unsustainability. By framing collapse not as an inescapable fate but as a call to rethink economic and social structures, collapsology could serve as an impetus for radical transformation rather than mere survivalist retreat. Instead of simply chronicling decline, a left-leaning collapsology could challenge the systems driving ecological and social devastation, mobilizing action rather than reinforcing despair.[21]

However, in practice, it can be said that the practice of preparing for the apocalypse is mostly in the hands of the right-wing. Apocalyptic narratives are frequently intertwined with the belief in Aryan purity, reinforcing a vision of an inevitable final battle that will determine the fate of civilization. Today’s fascists often employ Christian eschatological metaphors, invoking the idea of an impending Armageddon in which divine intervention punishes sinners through disasters, wars, and crises. These catastrophic events are not merely seen as destruction but as necessary precursors to a purified world order, offering a moral justification for political and social cleansing. Over time, this apocalyptic rhetoric delineates clear battle lines between the righteous and the corrupt, further solidifying a binary worldview that fuels reactionary mobilization. By constructing a framework where collapse is framed as both inevitable and desirable, right-wing apocalypticism fosters an exclusionary, militant mentality that not only anticipates but actively prepares for societal breakdown as a means of ushering in a new order.[22]

Dystopian cinema, particularly franchises like “The Walking Dead,” can serve as a guide for envisioning alternative futures beyond apocalyptic despair. While the series may appear ideologically neutral, or even right-wing, the show depicts a post-apocalyptic world where survivors form communes and self-sufficient communities, a narrative that can be reinterpreted in a way that opens possibilities for a leftist post-apocalyptic vision. Instead of reinforcing individualist survivalist tropes often associated with right-wing preparedness, these fictional communes could be reimagined as ecological, cooperative societies emerging from environmental collapse.

This perspective aligns with Antonio Negri’s notion that imagination is material, dynamic, and collective. Revolution, he argues, must be conceived beyond mere temporality—it is not only a horizon but also a measure of transformation.[23] Time, traditionally exploited as a quantitative metric of labor under capitalism, can instead be reclaimed as a qualitative measure of alternative possibilities. Reactionary mysticism, which relies on the manipulation of time to sustain exploitation, stands in contrast to revolution, which emerges through the phenomenology of constructing new temporalities. In this sense, dystopian narratives, rather than being passive reflections of decline, can fuel a radical imaginary that envisions communal survival, solidarity, and resistance to capitalist collapse. Science, labor, and the collective intellectual organization of human effort hold the potential to reshape power—not merely in opposition to authority, but in the creative destruction of oppressive structures. As the classics remind us, imagination is the most concrete force in shaping temporal possibilities, and within it lies the potential for a leftist survivalism that turns crisis into a foundation for collective renewal.[24]

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Dave Canterbury, Bushcraft 101: A Field Guide to the Art of Wilderness Survival (Simon and Schuster, 2014), 13.

↩ -

Raymond Mears, Bushcraft (Hodder & Stoughton, 2002).

↩ -

Susannah Crockford, "Survivalists and Preppers," Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (2021), 1.

↩ -

Kezia Barker, "How to Survive the End of the Future: Preppers, Pathology, and the Everyday Crisis of Insecurity," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45, no. 2 (2020), 485-489.

↩ -

Foti Benlisoy, Kapitalist Kıyamet - Sermaye mi Dünya mı? (Habitus, 2021), 89.

↩ -

André Gorz, İktisadi Aklın Eleştirisi: Çalışmanın Dönüşümleri - Anlam Arayışı, 2nd ed., trans. Işık Ergüden (Ayrıntı, 2007), 22.

↩ -

Daniel Bensaïd, Köstebek ve Lokomotif, trans. U. Uraz Aydın (Yazın Yayıncılık, 2006), 29.

↩ -

Greg Garrard, Ekoeleştiri: Ekoloji ve Çevre Üzerine Kültürel Tartışmalar, 3rd ed., trans. Ertuğrul Genç (Kolektif Kitap, 2020), 63.

↩ -

Anne Küppers, "'Climate-Soviets,' 'Alarmism,' and 'Eco-Dictatorship': The Framing of Climate Change Scepticism by the Populist Radical Right Alternative for Germany," German Politics (2022), 27.

↩ -

John C. Carney, "Deciphering Crypto-Fascism," Philosophy and Global Affairs 1, no. 2 (2021), 209.

↩ -

Nigel Copsey, "‘Fascism… but with an Open Mind.’ Reflections on the Contemporary Far Right in (Western) Europe: First Lecture on Fascism – Amsterdam – 25 April 2013," Fascism 2, no. 1 (2013), 10.

↩ -

Samantha Kutner, Swiping Right: The Allure of Hyper Masculinity and Cryptofascism for Men Who Join the Proud Boys (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2022), 14.

↩ -

Michael Löwy, Devrim Bir İmdat Frenidir, trans. Alev Er (Sel, 2021), 29-55.

↩ -

Enzo Traverso, Geçmişi Kullanma Kılavuzu, trans. Işık Ergüden (Versus, 2009), 80.

↩ -

Wendy Brown, Tarihten Çıkan Siyaset, trans. Emine Ayhan (Metis, 2010), 193.

↩ -

Walter Benjamin, Pasajlar, 18th ed., trans. Ahmet Cemal (Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2022), 40-41.

↩ -

Marc Berdet, "L’Ange de l’histoire. Walter Benjamin ou l’apocalypse méthodologique," Socio-anthropologie 28 (2013).

↩ -

Gregory Marks, "Apocalypse Never: Walter Benjamin, the Anthropocene, and the Deferral of the End", La Trobe (2021), 186.

↩ -

Pierre Charbonnier, "The Splendor and Squalor of Collapsology," Revue du Crieur 2 (2019), 88-95.

↩ -

Ibid, 88-95.

↩ -

Kirk A. Bingaman, "The End of the World as We Have Known It? An Introduction to Collapsology," Pastoral Psychology 71, no. 6 (2022), 757.

↩ -

Chip Berlet, "Christian Identity: The Apocalyptic Style, Political Religion, Palingenesis and Neo-Fascism," Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 5, no. 3 (2004), 478.

↩ -

Antonio Negri, Devrimin Zamanı, trans. Yavuz Alogan (Ayrıntı, 2003), 38.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩