In my last article in politics and games, I hinted that I have beef with game playing under capitalism. I am preparing to deliver it on a platter, seasoned by the spice of industrial sociology. While labor and play may seem diametrically opposed, they are secretly connected. Play is how we learn to labor as children; games are how we hone our performance. My lifetime of game playing has appeared this way in my work—the more I have treated my work as a game, the better I have done. To develop this theory, I will run through the basics of the labor process, how sociologist Michael Borowoy ties play into worker self-exploitation, and then revisit the example of Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please to describe how a specific system of game mechanics can discipline players much as a wage system disciplines workers. The result: the leisure of play as an illusion.

Labor Process and Worker Consent

The labor process, in Marxism, is the precise definition of the human actions that socially constitute production, with what tools. Capitalists often use technology and social organization to obscure the labor process, which helps them reduce costs, e.g., responsibility for social reproduction, and exploit labor arbitrage (what do you think AI is doing?). You can define labor processes narrowly by a specific job or broadly by production, e.g., of a type of commodity: the computer you are using to read this required hazardous rare-earth mineral mining and will, in its time, produce hazardous electronic waste. For an example of how non-intuitive the scope of a labor process can be, in an ethnography of 1990s copier mechanics in Silicon Valley, Julian Orr defines mechanics’ labor process as being as much about managing territory and customer expectations as restoring copier function.[1]

Building on Harry Braverman’s Labor and Monopoly Capital: Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, labor-process adherents track down and identify the broader work involved in capitalist production to provide strategic insight into how they might be disrupted or altered. It is a social-science project that is, even in the United States, amenable and useful for critiques of capitalism. The breakdown of Toyota production in a prior Cosmonaut article, “Modern Industry and Prospects for Socialism,” could serve as one example of this kind of analysis.

At first blush, play seems to have no place in the labor process. It is often glossed as non-productive behavior, by definition. In fact, play can better be understood as an attitude towards behavior rather than a discrete behavior itself. Play is exploratory and an expression of will and agency by the player. Almost anything can be done playfully, although that is harder to do once the rules of engagement are worn in enough. A chess game between grandmasters resembles ritual or work more than play. Memorizing chess openings, predicting your opponent’s turns, seeing the interlocking heuristics of pieces and their positions—all this reduces your ability to properly play chess as a game. The more you learn, the further and further the horizon of open play recedes. Boredom creeps into the game, and the skilled find themselves only interested in competing against their equals.

In his 1981 ethnography of a machine shop, Manufacturing Consent, sociologist Michael Burawoy set out to answer not how capitalists are able to exploit through coercion but rather how willing workers are to participate in their exploitation. In the shop where he worked, Burawoy was fascinated by the combination of salaried and piecemeal work that management had in place. Machine operators would always earn a flat rate (i.e., goldbricking) but could earn up to 140% of that salary based on how much they exceeded set production quotas (which the operators termed “making out”). Burawoy was surprised by the frequency and pride with which experienced workers would make out and their disappointment and anger at falling short of their internally imposed goals or being forced to goldbrick a day. He realized—they were playing a game.

Operators’ ability to make out depended on the machines they were assigned to operate, their own skill, and relations within the shop floor itself:

This game of making out provides a framework for evaluating the productive activities and the social relations that arise out of the organization of work. We can look upon making out, therefore, as comprising a sequence of stages—of encounters between machine operators and the social or nonsocial objects that regulate the conditions of work. The rules of the game are experienced as a set of externally imposed relationships. The art of making out is to manipulate those relationships with the purpose of advancing as quickly as possible from one stage to the next.[2]

For example, skilled operators built up hidden “kitties” of produced parts to delay handing them in. On easy days, they could far exceed the parts needed to reach 140% pay but preserve the excess parts in their kitty for a day when production was more difficult, but they still wanted to make out.

Burawoy also recounts how the need to retrieve machine tools from crib tenders and coordinate with truck drivers for the delivery of parts brought social relations into operators’ production process. Auxiliary workers like crib tenders and truck drivers had their own labor process and pay scales independent of the operators. They were, thus, structurally indifferent to the needs of the operators, who were playing at making out. This indifference produced power on the floor. If an operator pissed off a crib tender, he could expect to lose time waiting for his tools. Conversely, subtle support and friendship would give him preferential treatment. To make out successfully, operators had to navigate these successive stages of the labor process and understand how relative success or failure at one would affect the next (which they referred to as understanding the “angles” of the job). That is, playing the game of “making out” often required operators to see workers in another part of the production process as obstacles to be overcome.

Further, there was social status tied to the ability to make out. As an untrained graduate student, Burawoy was inept as a machine operator when he first began his ethnography. This inability made him socially invisible. Once he began to make out, however, he was allowed into the social world of the other workers:

It was a matter of three or four months before I began to make out by using a number of angles and by transferring time from one operation to another. Once I knew I had a chance to make out, the rewards of participating in a game in which the outcomes were uncertain absorbed my attention, and I found myself spontaneously cooperating with management in the production of greater surplus value. Moreover, it was only in this way that I could establish relationships with others on the shop floor. Until I was able to strut around the floor like an experienced operator, as if I had all the time in the world and could still make out, few but the greenest would condescend to engage me in conversation. Thus, it was in terms of the culture of making out that individuals evaluated one another and themselves.[3]

Compared to a chess grandmaster bored by rote opening sequences, Burawoy was at first uninterested by the (to him) incomprehensibly convoluted labor process of the operators. As he learned its elements and, more importantly, how to navigate it to increase his own pay, he found himself not only interested but willing to play. At scale, the result was not just that operators had a culture of consenting to enthusiastic production of surplus value: other workers actually became sources of conflict and friction in their labor process. Burawoy argues that this entire partial piecework system systematically directed worker grievances out laterally towards other workers, rather than upwards at the bosses.[4] This was not a deliberate management strategy (because this process depended on discontinuities of social connection across the workplace), but obviously, they were pleased with the result.

The image that Burawoy paints of the machine operators and himself is one of grim gamesmanship. But at the same time, like any social system, there was a sense of commitment and even loyalty to this system. Making out was what gave these workers a sense of social worth. From his experience, Burawoy makes a strong claim that game behavior like this can redefine both the process and subjective experience of labor:

Any game that provides distinctive rewards to the players establishes a common interest among the players—whether these are representatives of capital or labor—in providing for the conditions of its reproduction. Insofar as games encompass the entire labor process, the value system to which they give rise will prevail on the shop floor.[5]

No one likes to have their toys taken away.

Pushing Paper in Papers, Please

Let’s look at the other side of the coin now: labor in play. As I discussed in “The Reign of Play,” there are plenty of turn-based and real-time games that simulate a capitalist economy and commodity exchange, eg, Europa Universalis IV or Offworld Trading Company. But labor is common as well, particularly in real-time games like Cart Life, Hardspace: Shipbreaker, and many survival horror games. For my case study, however, I will use Lucas Pope’s 2013 title Papers, Please, a celebrated dystopian simulation of border security work.

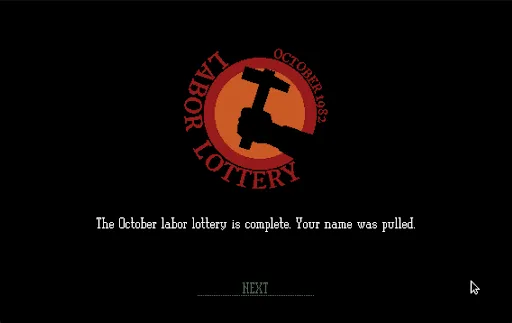

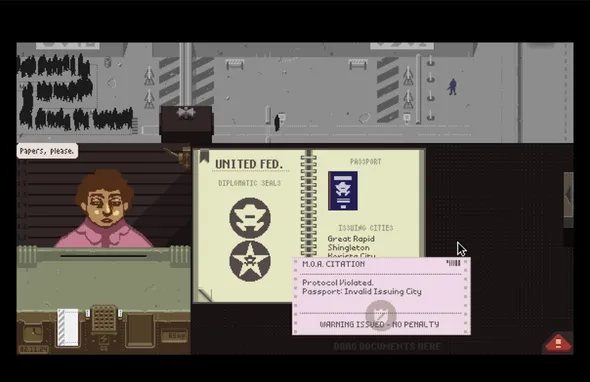

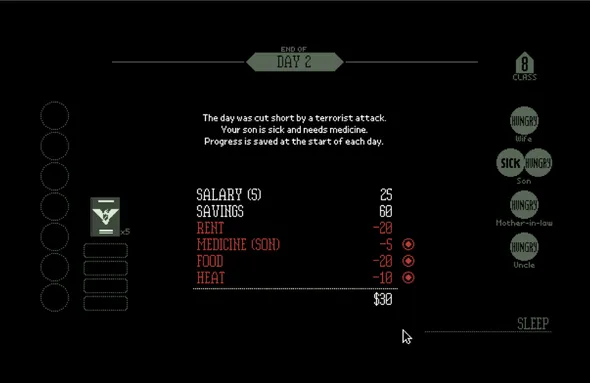

Papers, Please takes place in the fictional communist Eastern Bloc country of Arstotzka. You win the October labor lottery, which grants your family housing and you a position as an immigration officer. The Arsztokza border is newly opened, with newspaper headlines promising increased trade and prosperity. The line of massed humans outside your booth is more than can ever be processed. Throughout a simulated day, you call people forward one-by-one to present their passports and other paperwork for your approval. The majority of actions you take are shuffling papers around on your desk with your mouse, until you’re ready to approve or deny someone’s petition to travel. You are paid a flat wage for each person that you correctly admit to Arstotzka. You have several warnings per day before mistakes start causing government fines to accumulate.

While Papers, Please revels in a communist aesthetic, this is only the visual conceit of the game.[6] Its critique is actually most forceful when directed against capitalist wage labor. Every discrete day, you need to earn a minimum wage to make rent and pay for food and heating for your family (you lose if they all die; so your family members are fungible, except the last). With its analog controls, there are several strategies for processing paperwork as quickly as possible. You can get faster at flipping through documentation pages as you check each individual item for discrepancies: their name, face, weight, nationality, passport expiration date, purpose for travel, work permit validity, etc. You can memorize the issuing cities for each country’s passports to save you time. You can also… guess. The game does not care as long as you have enough money at the end of the day to pay your way to the next. Burawoy’s comment about investment in the social reproduction of a particular process here is inflicted on the player. If you want to play more, you need to learn who and who does not pass border regulations each day.

We can also see Burawoy’s dispersion of conflict across a workplace in Papers, Please. The way narrative events and mechanical rules play out most often pits you against other agents in the world through their effect on your wages and labor. You experience a terrorist attack not as an attack on your person or family but as a decrease in the length of your workday (and so your wages) and an increase in the complexity of your labor and the required documentation. The escalating documentary requirements the Arstotzkan state imposes on your labor make the game increasingly difficult and engender your resentment. But they are not something that can be negotiated with, only accommodated to. Your fellow Arstotzkan citizens have the least stringent requirements for travel, so they make it easier for you to earn your wages. The sight of an Arstotzkan passport slid onto your desk is a moment of relief. Travelers from neighboring Kolechia often require detainment, which slows your pay rate. Your family consumes food and heat but you can opt to pay for both, one, or none each day—one strategy for survival is alternating between feeding your family and heating your home. And so, a complex labor process is transmuted into letting your family slowly freeze.

The process of play is, in this case, a simulated labor process. For example, another title by Lucas Pope, Return of the Obra Dinn, magically simulates a different kind of unhurried, salaried, actuarial labor: the player travels through time to determine causes of death and liability for the entire crew and passengers of a derelict ship. Everyone is dead, but some people have estates. The more you do, the more accurate your accounting of awards and fines is. In comparison, playing Papers, Please is stressful. It feels like a job.

Disenchanting the Magic Circle

There is a concept popular among game-design educators, which they appropriated from Dutch anthropology: “the magic circle,” a term used by Johan Huizinga in his Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. The basic idea is that play asks us to draw a boundary within which the rules of life differ, and we must experience our identity and the world around us in a new way:

Within the magic circle, special meanings accrue and cluster around objects and behaviors. In effect, a new reality is created, defined by the rules of the game and inhabited by its players. Before a game of Chutes and Ladders starts, it’s just a board, some plastic pieces, and a die. But once the game begins, everything changes. Suddenly, the materials represent something quite specific. This plastic token is you. These rules tell you how to roll the die and move. Suddenly, it matters very much which plastic token reaches the end first.[7]

In this way, it is impossible to play a game to which you do not in some bare, minimal way, consent.[8] It is proprioception and identification (or dissociation) taken to the extreme. This appropriation read deeply into only a few lines of Huizinga’s text, but debunking “the magic circle” has become a popular exercise in academic games writing.[9] When we think of how games are treated as a cultural form, however, we often find that they are given magic circle treatment. As leisure time, games are often informally understood as creating a space outside of capitalist production and consumption, perhaps except as entertainment. This might be a legacy of games’ status as subcultural until fairly recently. The current pricing and distribution systems for games (digital especially) make this view hard to justify. Single-cost games have been replaced with subscriptions, early-access release models, and crowdfunding. These allow developers to extend their profit beyond a single enormous gamble the week they launch—more and more games are not simple commodities that can be owned. Instead, through subscriptions and digital distribution, they create a continuous relationship of consumption between players and games producers.

I discussed “The Reign of Play” how the experience of playing a game can shape players’ subjectivity in a way that is helpful for political education, even in the satirical manner of Paolo Pedercini’s Molleindustria Games of Oiligarchy, Rules & Roberts, or Democratic Socialism Simulator. But games like Papers, Please also teach us to discipline ourselves if we want to continue to play. Over time, this can help us develop skills useful to us beyond the game. But we also take something more than that with us—a mindset that confuses play for labor (and vice versa). “Serious games” and gamification are two overt ways that bosses have tried to harness this kind of socialization. The enticements, however, to game our way through labor processes extend far further. If game players are all optimizing our workplace performance for production inspired by the games we play, I fear the widespread result is the kind of lateral diffusion of conflict that Burawoy described.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Deliberately including seemingly non-work processes, like the joking or practice of telling war stories about repair work that Orr describes, is an important aspect of the labor-process project. See: Julian E. Orr, Talking about Machines: An Ethnography of a Modern Job (ILR Press, 1996).

↩ -

Michael Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process under Monopoly Capitalism (The University of Chicago Press, 1982), 55.

↩ -

Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent, 64.

↩ -

For example, “‘Going slow,’ aimed at the company redounds to the disadvantage of fellow workers … Common sense might lead one to believe that conflict between workers and managers would lead to cohesiveness among workers, but such an inference misses the fact that all conflict is mediated on an ideological terrain, in this case the terrain of making out. Thus, management-worker conflict is turned into competitiveness and intragroup struggles.” See: Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent, 66–7.

↩ -

Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent, 85.

↩ -

Much of the games-studies literature on Papers, Please never quite gets past a simplistic reading of the game as just a critique of Arendtian totalitarian bureaucracy. While he uses provocative conceits for his games, Lucas Pope does not by-and-large seem to put great effort into social verisimilitude as a designer. He recently received criticism for his other title The Return of the Obra Dinn and how its representation of 19th-century mercantile shipping sidesteps nearly any acknowledgment of racial capitalism and colonialism. See: Patrick Jagoda and Ashlyn Sparrow, “The Procedural Unconscious: Video Games and the Nonsynchronous Contemporaneity of Racial Capitalism,” ROMchip 6, no. 2 (2024), https://www.romchip.org/index.php/romchip-journal/article/view/199.

↩ -

Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals (MIT Press, 2004), 96.

↩ -

Echoes of Burawoy: “The very activity of playing a game generates consent with respect to its rules. The point is more than the obvious, but important, assertion that one cannot both play the game and at the same time question the rules. The issue is: which is logically and empirically prior, playing the game or the legitimacy of the rules?” Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent, 81.

↩ -

One of the authors of this appropriation claimed it was never to have been taken so reductively by readers—it was meant as a tool to help design students conceptualize the effects of game mechanics. See: Eric Zimmerman, “Jerked Around by the Magic Circle: Clearing the Air Ten Years Later,” Game Developer, February 7, 2012, https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/jerked-around-by-the-magic-circle---clearing-the-air-ten-years-later.

↩