Adam Turl’s Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted from Heaven & Earth, published by Revol Press earlier this year, is a slim chimera of a book. In it, as in their own artwork and cultural organizing, Turl sets out to imagine what it would take to create art by and for what he calls “gothic futurist working class subjects.”[1] These are precarious workers who presumably share a global subjectivity conditioned by what Leon Trotsky called uneven and combined development (UCD). Turl contends that classic examples of UCD, such as the close co-existence of both the most archaic and most advanced forms of economic organization in late-Tsarist Russia, have always been central to capitalism the world over. The logic of UCD is built into business strategies such as planned obsolescence, for example. It is responsible for a convulsive march forward during which capital never ceases to reinvent itself. The term “gothic futurism” is meant to describe how this warpath is littered with holdovers from the past that refuse to die. Those born along the way, bastards of neoliberalism, must embrace their hybrid, monstrous natures and rise to become the gravediggers of capitalism once and for all. Turl suggests that in the visual arts, they do so by producing art that emerges from and seeks to narrate the conditions of this subject’s creation, as well as the self-organization of cultural spaces outside the capitalist art market and the neoliberal university.

The thesis of Gothic Capitalism, like the existential loneliness of Frankenstein’s monster, is driven by rage at the conditions of its own creation. Unlike the monster, who is single-minded in his quest to hunt his creator to the ends of the earth, Turl’s text reads as confused in its aesthetic and political mission. The first three pages of the book contain a clear enough articulation of “gothic" as a category, which Turl uses to describe a contemporaneity marked by the uneasy coexistence of high technological advancements alongside revivalism and ruins, as well as what Turl sees as the potentially explosive nature of this coexistence. Turl calls on artists to “wrest art away from the dominant culture, using the art space as a theatrical, social and spiritual space that gives voice to proletarian narratives: the narratives of those who hold the power to abolish capitalism and create a genuine and democratic society.”[2] Shortly thereafter, however, Turl begins to lose the plot.

Chapter One is the re-working of an article that Turl originally published in the periodical Red Wedge, of which they were a co-editor, in 2014. In its opening section Turl paraphrases a 1996 secondary source that describes Bolshevik Revolutionary Aleksandra Kollontai’s novel Vasilisa Malygina as a gothic critique of the New Economic Policy (NEP). The novel’s proletarian protagonist, like the heroines of one strand of popular late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century Romantic literature, becomes trapped in a mansion. Turl introduces the reader to poor Vasilisa to associate the gothic with uneven development. The mansion is a recurrence of the economic order toppled by the Russian Revolution and belongs to her NEP-man former lover. It also sets the stage for Turl ascribing a gothic character to contemporary capitalism in the US. Among the anachronistic ruins and “gothic artifacts” that give US neoliberal capitalism this quality, according to Turl, are those produced by Left political movements in the second half of the twentieth century.

Adam Turl’s Socialist Surrealism

Turl argues that the status of the cultural landscape of the twentieth century Left, reduced in the present to artifacts subdued by gothic capitalism, requires that contemporary Left-wing cultural producers create more than simply didactic propaganda. To aid in imagining what this contemporary, non-propaganda art might look like, Turl introduces the term “gothic Marxism” as a foil to gothic capitalism. Gothic Marxism is not an economic philosophy as much as it is an aesthetic program that borrows heavily, if inconsistently, from both the Marxist humanism of Austrian communist Ernst Fischer’s 1959 text The Necessity of Art, and an interest in psychoanalysis on the part of the socialist camp of the early- to mid-twentieth century, international Surrealist movement in the literary and visual arts.[3]

Implicit in Turl’s invocation of Surrealists like poet André Breton is the heady aesthetic debate around Realism that preoccupied committed artists of many political inclinations over the course of the 1930s. Turl denies themselves the opportunity to productively revisit this conversation through the lens of “capitalist Realism” as described by Left literary critic Mark Fisher, as they fall on the sword of their own anachronistic anti-Soviet sentiment, however. This can be read between the lines of his antipathy toward “propaganda.”

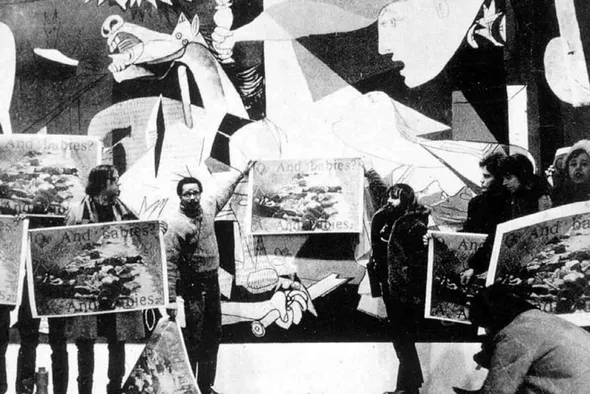

Indeed, many Left artists in Europe and the Americas during the 1930s, who considered their work to be in dialogue with the history of Realism, positioned themselves against an official style of visual and literary representation, often historical and politically-didactic or socially-instructive in content, that dominated Soviet cultural production by the mid-1930s. André Breton, who co-authored a 1938 “Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art” with Leon Trotsky and socialist muralist Diego Rivera, was one such artist. Frida Kahlo, who was professionally and personally affiliated with all three, took her own subjectivity, interpellated by Mexican colonial history, the proximity of US empire, class society, and the patriarchy, as the primary muse for her startling, figurative self-portraits, did not accept the label “Surrealist” given to her by Breton.[4] If the curators of her Mexico City house museum are as faithful to the original placement of her effects as they claim, she died with portraits of Stalin, Engels, Lenin, Marx, and Mao at the foot of her bed [Figure 1].

Turl’s early invocation of the distinction between “propaganda” and “art” bodes ill for the rest of the book, and Kahlo’s is an important example to keep in mind because she very clearly lays bare how this distinction is meaningless. Kahlo, Rivera, Breton—even Trotsky himself—enjoyed the patronage of governments, or individual capitalists, eager to outmaneuver their real or perceived, Soviet-aligned enemies. To discuss the political character of an artist’s aesthetic output without analyzing the political context in which it exists is naïve at best. This is true for our own moment as well, and Turl asks a big, urgent question at the end of this chapter: “[t]he question for leftist artists today is: how do we take the contradictions borne of the individual artistic tendency while simultaneously collectivizing them to help develop critical and revolutionary impulses?”[5]

Indeed, the eighteenth-nineteenth century, Romantic caricature of the artist as the genius individual, which Turl correctly identifies as tailing the development of mercantile capitalism, persists into the present. The individual artist is a gothic protagonist in an equally gothic capitalist art market. The art market exists, as it always has, to provide another avenue by which the ultra-wealthy may hide or launder their money. It is sustained by a highly specialized, yet heavily debt-burdened reserve army of art teachers, adjuncts, freelancers, and otherwise precariously employed creative laborers that artist, activist, and academic Greg Sholette evocatively calls “dark matter.”[6] It holds the university in its thrall, producing yea-saying academics to legitimize its ideology. It presents immense barriers to success for artists not born into privilege. It produces boring, lazy art for rich, lazy people.

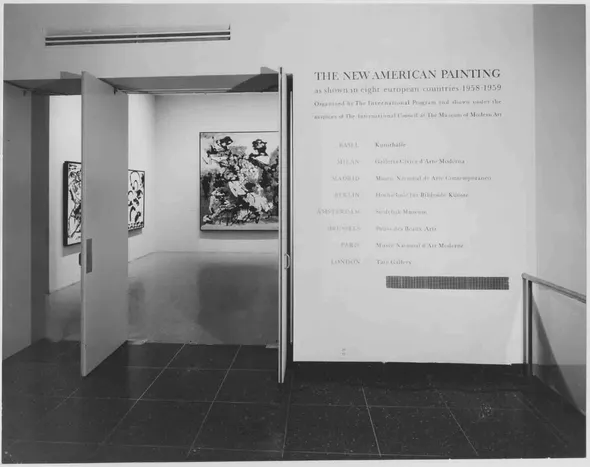

Unfortunately, the 110 pages that follow the end of Chapter One provide only the rarest glimpses of what could even begin to answer Turl’s Big Question about fostering the creation of socialist subjectivity among artists under these hostile conditions. Turl tries to do too many things, go too many places, in too little time, and the clarity of their thesis suffers for it. The concrete organizational or aesthetic recommendations that Turl does introduce early on—they recommend that artists more-enthusiastically embrace narrative techniques in their work, for example—could do with historical contextualization: what were some of the ebbs and flows of narrative representation in the fine art of Europe and the Americas over the course of the twentieth century? It’s directly related to those Popular Front debates about realism in which Breton and others participated. It persists into the Cold War, and informs the aesthetic concerns of anti-Soviet, one-time-Trotskyist intellectuals such as High Modernist kingmaker Clement Greenberg, and the theoretical questions of the commodity status of the artwork that pre-occupied the artistic inheritors of the so-called New Left [Figs. 3 and 4].[7] Turl dives into this last subject without so much as a breath, assuming that the reader is right there with them. The reader is lost in the woods.

Straw Men and Buzzwords

Turl demonstrates their commitment to the “individual artistic tendency” by taking copious pot-shots at Soviet Socialist Realism. However, their understanding of both official and unofficial Soviet visual art in historical context, at least as demonstrated in Gothic Capitalism, seems built on the brittle foundation of media theorist Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism, itself a gothic, Cold War artifact.[8] In this short text, originally published in German in 1992, Groys provocatively argues that the Soviet avant-gardes of the 1910s and ‘20s essentially became the handmaidens of the Great Terror when they tied their creative output to the success of the Bolshevik project.[9] Its 2011, Verso Books reissue fell on fertile ground in the corners of the contemporary art world, and its academic and non-profit auxiliaries, most preoccupied with critical theory. Between the late-1990s and 2010s, these were obsessed with debating the pros and cons of the aesthetic components of what they described as the twentieth century’s failed Modernist utopias.

That Turl's text should revisit these debates in Gothic Capitalism owes perhaps to the fact that the book draws heavily on work that Turl and associates published in the arts and culture periodical Red Wedge in the 2010s, as well as Turl’s 2016 MFA thesis. Turl’s anachronistic anti-Soviet sentiment, however, does not clarify or strengthen their call for socialists to develop an attitude toward art that both honors individual self-expression and aspires toward collective action.

To justify their belief in the working class as an “intervening historical subject,” their commitment to “metanarrative (the idea of totalizing systemic change),” and also to differentiate their aesthetic project from that of artists and theorists committed to a “discursive notion of power,” Turl dunks on “postmodernism.” The trouble is, the aesthetic strategies that Turl proposes for the “gothic futurist working class subject,” such as embracing narrative storytelling and theatricality, are art historical hallmarks of postmodernism.[10] Visual artist and one-time Black Flag bassist Raymond Pettibon, whose “strong” images, often drawn from pop culture and suffused with punk irony, Turl posits as antidotes to an easily salable kind of abstract art that briefly but controversially dominated the capitalist art market for a few years in the 20-teens, is a good example of this.

Like many other works of contemporary art criticism, Gothic Capitalism draws too much of its aesthetic urgency from a sometimes-poetic blurriness around discrete concepts and contexts. If one allows, like Turl does, that understanding trends in the capitalist art market of the past forty years is useful to socialist organizing, however, then it matters that Gothic Capitalism is peppered with sloppy art history and ill-defined jargon.[11]

Moreover, Turl often assumes a familiarity with recent artistic currents, artists, and artworks that is unfair to expect of an audience not already conversant in these topics—regardless of their broader level of education. There are, perhaps, material explanations for the text’s lack of clarity and cohesiveness. The book would gain a great deal from the inclusion of images, for example, but acquiring the reproduction rights might be prohibitively expensive for a small, independent press. Similarly, Turl’s text would have benefited from a more rigorous editorial process but again, this requires resources. The very existence of this book may be the result of the academic professional imperative to publish or perish. Such conjectures as to the origins of its shortcomings do not make Gothic Capitalism a less discouraging read.

In Search of Self-Organization

By the end of Chapter Three, Turl hits on the question of artistic self-organization. If contemporary socialists who are interested in the arts should heed the words of Adam Turl on any subject, it’s artistic self-organization. Turl is an accomplished cultural organizer who co-founded the arts and culture periodical Red Wedge along with other International Socialist Organization (ISO) comrades in 2012 and co-founded The Locust Arts and Letters Collective (LALC), publishers of the quarterly Locust Review with their partner, poet Tish Turl, in 2019. Together they operate the Born-Again Labor Museum, an explicitly leftist community center and exhibition space in Carbondale, Illinois.

These and other endeavors in which Turl has played a decisive organizing role have brought a number of skilled and like-minded artists into each other’s orbit and resulted in a great deal of dynamic collaboration. Turl’s visual art is often brilliant. Their Fast-Food Parking Lot’s Wives (2021-2024), for example, is both punny and poignant. The Wives are a series of found-object sculptures in which the disposable salt packets that accompany take-away orders are arranged in awkward, yet delicate, pillar forms. The humble, readymade materials of their creation are familiar, yet they take on a strangely epic significance when multiplied and recontextualized. With a gentle, black humor Turl recalls the Biblical tale of the woman turned to salt as punishment for looking back on her ruined city, albeit for a contemporary audience. This audience is likely grieving its own world, engulfed by flames.

Incidentally, the aesthetic and theoretical preoccupations evidenced by the work of artists such as Turl, and prominent LALC member Anupam Roy, tend to align with those expressed in Turl’s book. Reading Gothic Capitalism also sheds a great deal of light on the artists by whom and movements by which Turl is influenced. Confusion awaits those who did not expect from Gothic Capitalism a LALC manifesto or extended artist’s statement on Turl’s part, however. Moreover, Turl does themselves and their readers a disservice when they treat that important question of “individual artistic tendency” versus “collectivization” as one of ideology, couched in aesthetics, as opposed to primarily one of the ideologically motivated decisions that inform access to resources for cultural self-organization. Their text is filled with examples of artists whose work is acquiescent to the demands of the capitalist art market or accommodationist to the demands that corporate donors make of the private museum. Often, this is accompanied by shock over the ways in which such demands appropriate the visual or rhetorical language of past Left and socialist movements.

The functional relationship between aesthetic and political radicalism is tenuous if the cultural producers in question are not explicitly creating art for political movements in the first place, so Turl’s indignance is somewhat misplaced. Yes, artists creating art for the capitalist art market produce work that provides ideological cover for capitalism in all sorts of subtle ways. Yes, leftist artists ought to self-organize, but how? Though Adam Turl has ample experience in this area, the answers that Turl offers amount to some mumblings about “DIY,” a page and a half of generalizations about the aesthetics of Black Panther Party Minister of Culture Emory Douglas, and a list of the LALC’s accomplishments tacked on at the end.

The cultural lives of Left organizations will not be made more dynamic or sustainable simply by introducing aesthetic choices that are, by warmed-over Cold War metrics, more correct than those made by socialists in the past. They are also not enriched by poorly edited volumes that critique capitalist art world developments from over a decade ago, albeit “from the Left,” without contextualizing them or making a compelling case for why readers who are not already intimately familiar with contemporary art should care about them.

Considering the current, anemic state of the US Left, and the challenges faced by its already-existing institutions, Turl could have made a much more vibrant contribution to the conversation around contemporary art and politics by sharing some secrets of a relatively successful cultural organizer. Of course, there are strategic reasons one might stay quiet about one’s organizing tactics. The final pages of Gothic Capitalism, however, where Turl finally speaks on their own behalf, and on behalf of the LALC, suggest that Turl is not interested in maintaining a low profile. Had they started Gothic Capitalism here, it would be a book worth reading, and widely.

Appendix: Images

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Adam Turl, Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted from Heaven & Earth (Revol Press, 2025), 7.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

Ernst Fischer, The Necessity of Art: A Marxist Approach (Penguin Books, 1963).

↩ -

Charlotte Barat, “Frida Kahlo,” Museum of Modern Art, 2016, https://www.moma.org/collection/artists/2963.

↩ -

Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 27.

↩ -

Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, (London: Pluto Press, 2011).

↩ -

“Abstract art was the main issue among the painters I knew in the late thirties. Radical politics was on many people's minds, but for these particular artists Social Realism was as dead as the American Scene. (Though that is not all, by far, that there was to politics in art in those years; some day it will have to be told how "anti-Stalinism," which started out more or less as "Trotskyism," turned into art for art's sake, and thereby cleared the way, heroically, for what was to come.)” See: Clement Greenberg, “The Late Thirties in New York (1957;1960),” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Beacon Press, 1961), https://monoskop.org/images/1/12/Greenberg_Clement_Art_and_Culture_Critical_Essays_1965.pdf, 230-235.

↩ -

Readers interested in a measured, meticulously researched historical account of Soviet Socialist Realism should consider the work of art historian Christina Kiaer. See, for example: Christina Kiaer, Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism (The University of Chicago Press, 2024).

↩ -

Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (London, UK: Verso, 2011).

↩ -

Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 42-43.

↩ -

For example, Turl calls themselves a “Marxist in an irreal tradition.” Nowhere in the book is the term irreal defined. See: Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 95.

↩