Terror...often arises from a pervasive sense of disestablishment; that things are in the unmaking.

-Stephen King[1]

Before 1968, horror looked different. Not just different from what we in 2025 expect a horror film to look like, but different from the life of the typical moviegoer in the US. Horror meant the “Shock Theater” package of Universal monster movies shown on television, which were horrifying in their day but became less so as a result of overexposure and audience familiarity. It meant the British Hammer Horror adaptations of Dracula and Frankenstein. It meant Roger Corman’s versions of Edgar Alan Poe stories. It meant the gimmick-ridden films of William Castle. In short, horror took place somewhere far away, in a distant time period.

Part of this was the result of film’s tendency to adapt works from the previous century. Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde were all the products of the 19th century. Poe’s “The Black Cat” and “The Raven” were also loosely adapted into Universal horror films. There were also ever present concerns about censorship and a desire to avoid upsetting the authorities. From 1934–1968, filmmakers worked under the strict Hays Code, which regulated onscreen content. Even before the Code went into effect, state censors removed a scene from James Wale’s Frankenstein where the Monster accidentally drowns a girl by throwing her into a lake. A line where Doctor Frankenstein compares himself to God was excised in some markets over alleged blasphemy.

Some horror writers were aware of the genre’s seeming disconnect from everyday concerns. August Derleth wrote in his introduction to classically inclined ghost stories, “In this nuclear age, the potential horrors of which far exceed anything heretofore conceived in the creative imagination of man,” the stories within were “almost an anachronism.”[2] Conservative public intellectual, and sometime Gothic horror writer, Russell Kirk argued in a collection of his own short pieces that the horror genre might be a solution to the social upheavals of the time. He wrote, “having demolished… the whole edifice of religious learning… [a] return to the ghostly and the Gothick [sic] might be one rewarding means of escape from the exhausted lassitude and inhumanity… of the sixties.”[3]

1968 was a year of tumult. The US empire won a pyrrhic victory during the Tet Offensive. Dubček attempted to build “socialism with a human face” during the Prague Spring. Students and workers almost took down De Gaulle in France. Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King were both assassinated. After the latter’s killing, riots erupted in many major US cities. In Chicago, at the Democratic National Convention, a “police riot” resulted in numerous cases of brutality against peaceful anti-war protesters.

The chaos of the times was reflected in the changing face of the horror film, embodied by three titles that came out that year: Night of the Living Dead, Rosemary’s Baby, and Targets. These films differed in budget, production value, and the trajectories they sent their creators’ careers on. All, however, responded to the fears and anxieties audiences were feeling as the world’s foundations were shaken, if not toppled.

Many contemporary critics were largely blind to how these films engaged with the issues of the day. When they deigned to review them, it was often to tut-tut at their boundary pushing violence or sexual content. Although none of the filmmakers consciously set out to make a grand social statement, a few did recognize the significance of the year’s events as they related to their projects.

They Won’t Stay Dead

Night of the Living Dead created the modern zombie film. Despite historian Mike Kurlansky downplaying the film as “a type of cheap thriller done repeatedly since the 1930s,”[4] Night of the Living Dead was something new. Earlier zombie films, such as the Bela Lugosi-starring White Zombie, showed zombies as the result of voodoo magic. They served a witch doctor, and usually represented white, western fears of “primitive” foreign religion.

By contrast, the zombies in Night of the Living Dead are “a grimly hilarious cross-section of ordinary Americans.”[5] They are reanimated corpses from every background. Director George Romero called them “blue collar monsters” who could be “the neighbors.”[6] The zombies, referred to as “ghouls” in the film, attack and eat the living, with their bite serving to transmit the condition to others.

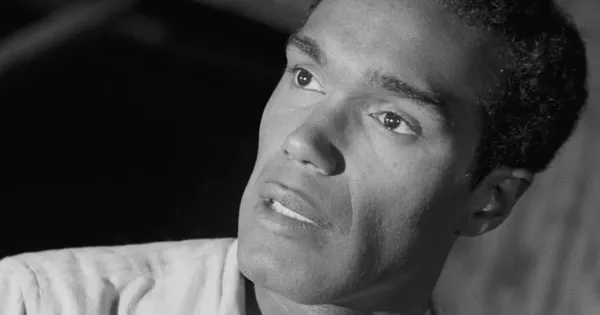

Reinventing this classic monster aside, the film’s other significance comes from casting Black actor Duane Jones in leading-role, Ben. Ben is unlike Black characters from previous horror films. They were superstitious, cowardly, and often the butt of racist jokes. Jones’ character breaks from these crude stereotypes. He is intelligent, decisive, and quick to action, unlike the white characters in the film.

The plot mostly takes place in a farmhouse under siege by the undead. The characters attempt to fortify the position and, when that becomes difficult, escape. Periodically the action is interrupted by radio and television broadcasts giving the impression of a world teetering on the brink of collapse. Ben is opposed in his plans by Harry, a white patriarch stranded with his wife and daughter. Harry’s opposition to Ben goes beyond any rational basis. Although it’s never explicitly stated, it’s likely that he is a racist.

The film ends with Ben, the sole survivor of the ghouls final assault, shot, and killed by a white mob looking for zombies. His corpse is dumped unceremoniously into a pile of bodies. “Okay, that’s another one for the fire,” a sheriff proclaims. Romero denied any explicit political commentary, saying “we were young bohemians, so in that sense we were automatically against authority. But I didn’t think it was political.”[7] He maintained Jones was hired simply because he gave the best performance.

This has not stopped critics from arguing the film is an allegory for racism in the United States. Danny Serge, writing in April 1970 for Cahiers du Cinema, took that view. J. Hoberman viewed the zombies as standing in for Richard Nixon’s “Silent Majority” opposing the changes of the 60s. He wrote, “as Gore Vidal pointed out, the phrase Silent Majority was a Homeric term for the dead.”[8] When Romero returned to the zombie genre, he seemed to take these readings in stride. Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, and Land of the Dead were all more explicitly satirical and politically charged.

Some reviewers were appalled by Night of the Living Dead. Variety wrote it cast “serious aspersions on the integrity and social responsibility” of the people who made it. “Until the Supreme Court establishes clear-cut guidelines for the anatomy of violence, Night of the Living Dead will serve nicely as an outer-limit definition by example.” Roger Ebert reviewed the film for the Chicago Sun-Times. “The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying,” he wrote. “When the hero is killed, that’s not an unhappy ending but a tragic one: Nobody got out alive. It’s just over, that’s all.” Ebert was shocked that theaters would show such a bleak film to children. He observed several of them crying throughout.

Pray for Rosemary’s Baby

Rosemary’s Baby was based on Ira Levin’s best selling suspense novel. The aforementioned William Castle purchased the film rights in hopes of directing. He wanted Rosemary’s Baby to be his ticket into the respectability he long craved. Yet Paramount Pictures was wary of Castle’s B-movie reputation. They gave him a producing credit and allowed him a cameo in the film but hired Roman Polansky to direct.

Rosemary’s Baby concerns Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse, newlyweds who have moved into the haunted Bramford apartment building in New York City. Guy is a struggling actor. Over the course of the film, the lengths he’s willing to go for professional success crystallize. He makes a deal with Satan to impregnate his wife, so she will bear the son of the Devil.

Although the Satanists are certainly menacing, it’s male domination of women in the traditional family that is the real villain. The Woodhouse marriage embodies Engels’ claim that “the modern individual family is founded on the open or concealed domestic slavery of the wife.” Guy’s name marks him as a stand-in for males generally. When Rosemary realizes she’s been sexually assaulted, Guy claims responsibility, rather than admitting that the Devil raped his wife as part of a Satanic ritual. At the time the film was made, marital rape was legal in all US states. Guy manipulates Rosemary throughout the film by gaslighting her and downplaying her concerns.

Guy feeds Rosemary a drugged mousse prepared by the neighbors, themselves members of the Satanic conspiracy that recruited him. The scene makes for even more uncomfortable viewing in light of Polanski’s drugging and raping of a thirteen year old in 1977. The director fled the United States rather than face justice. It’s a terrible historical irony that a filmmaker guilty of such crimes could make, along with Chinatown, two masterful films critical of men’s treatment of women.

The novel and film both explore the burgeoning disbelief in the Warren Commission’s conclusion that President Kennedy was not assassinated as a result of a conspiracy. In Levin’s novel Guy discusses the assassination over dinner after reading a book critical of the Warren Report.[9] The slain President himself appears in lapsed Catholic Rosemary’s visions during her Satanic assault. Later, Rosemary desperately asks a friend, “There are plots against people, aren’t there?” As the sixties continued, more and more viewers would answer in the affirmative.

The film’s occult subject matter was boundary pushing. Four theaters in Vermont banned the film after protests from the Burlington Catholic Diocese over its content.[10] The National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures gave the movie a condemned rating. A representative stated “the very technical excellence of the film serves to intensify its defamatory nature.” The film’s box office success showed the declining influence of this sort of clerical censorship. Within a few years, films like The Exorcist and The Omen delved even further into these Stygian depths and became blockbusters. Without the success of Rosemary’s Baby, it’s unlikely these films would’ve been made.

TARGETS are People... and You Could Be One of Them!

Director Peter Bogdanovich was given a seemingly impossible job to make Targets. B-movie kingpin Roger Corman told Bogdanovich to cobble together a film from Corman’s flop The Terror, and whatever footage he could shoot of Boris Karloff, who owed Corman a few more days of filming. The result was a swan song for Karloff’s brand of horror, and a welcoming in of the new.

Bogdanovich was not what one would call an especially political filmmaker. A companion recalled a dinner with Boganovich and director Howard Hawks. Hawks held forth on what to do with anti-war protesters: “If I was in charge, I’d arrest them all, cut their hair off. Shoot ’em!” Bogdanovich sat in silence. His motto was “it has nothing to do with us. We’re artists.”[11] Nevertheless, Targets remains a profoundly political film.

Part of that comes from circumstances beyond the filmmakers control. The film’s plot of a sniper on a rampage resonated in the year of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King’s assassinations. The director recalled after King’s murder that “half the studio wanted to kill it and the other half wanted to release it immediately.”[12] George Romero likewise said of King’s murder “Man, this is good for us.”[13]

Targets tells two stories that finally interact during the climax. In one, veteran horror actor Byron Orlock (Karloff) laments that his brand of horror has become passe and unable to deal with the real world. “My kind of horror isn’t even horror any more... Look at that,” he says pointing at a newspaper story on a supermarket massacre. “No one’s afraid of a painted monster anymore.” Karloff’s role is partly autobiographical. Although he had been a major star in the 30s and 40s, that star had dimmed considerably since.

In the other story, disturbed young Bobby Thompson, an obsessive gun collector, commits a spree of killings across Hollywood. Thompson wears a US Army jacket and served in the Vietnam War. It’s likely his wartime experiences contributed to his current instability. His sniper attacks on random civilians bring the war home to a civilian population ignorant of the costs of modern warfare.

Thompson’s lack of discernible motive baffled critic Howard Thompson of the New York Times. He wrote, the explanation behind “the random sniper-murder of innocent people is never answered in Targets. This is the only flaw, and a serious one.” Thompson’s confusion was understandable at the time, given the rarity of mass shootings. Charles Whitman’s Texas sniper attacks were both a then-recent exception and an influence on Targets. From a modern vantage point, however, the lack of discernible reasoning feels realistic, given the mass killings of our day that are the result of inscrutable motives, when there are motives at all.

The Nightmares Continue

In the aftermath of the release of these three films, horror’s engagement with social and political concerns only increased. In the ’70s, films like Deathdream, Dawn of the Dead, and Alien dealt with the Vietnam War, the growing consumerism based on credit, and amoral mega-corporations. The ’80s saw perhaps the greatest political horror film of all, John Carpenter’s class-war, Invasion of the Body Snatchers riff They Live. Even more recently, films like Us and Sinners have gone beyond Romero’s unintentional allegory to tell stories directly about racial oppression in the US. In a sign of Hollywood’s still insufficient progress, both of these films were directed by Black men. Jane Schoenbrum’s I Saw the TV Glow uses horror to relay the trans experience.

While the filmmakers behind these 1968 classics made no pretensions behind changing the world, in effect, that’s what happened. Although Night of the Living Dead, Rosemary’s Baby, and Targets never encouraged anyone to go on strike or occupy a university, 1968 was as pivotal to the horror genre as it was to global politics. Can anyone doubt that the years since have been the time of monsters?

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (Everest House, 1981), 22.

↩ -

August Derleth, “Foreword,” in Dark Mind, Dark Heart (Arkham House, 1962), vii.

↩ -

Russell Kirk, “A Cautionary Note on the Ghostly Tale,” in The Surly, Sullen Bell (Fleet, 1962), 232-236.

↩ -

Mark Kurlansky, 1968: The Year that Rocked the World (Random House, 2005), 183.

↩ -

J. Hoberman, The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties (New Press, 2003), 260.

↩ -

David Konow, Reel Terror: The Scary, Bloody, Gory, Hundred Year History of Classic Horror Films (St. Martin’s Press, 2012), 99.

↩ -

Jason Zinoman, Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror (New York, 2011), 106.

↩ -

Hoberman, 261.

↩ -

Ira Levin, Rosemary’s Baby (Signet, 1967), 82.

↩ -

UPI, “Vermont City Bans Rosemary’s Baby,” Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1968.

↩ -

Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (Simon and Schuster, 1998), 116.

↩ -

Zinoman, 43.

↩ -

Ibid, 42.

↩