…aim the workers’ fire straight at the employers and catch the union bureaucrats in the middle. If they didn’t react positively, they would stand discredited.

–Farrell Dobbs[1]

Introduction

A labor union is a particularist form of organization. By its very nature, it does not transcend a section of the working class and that section’s particular interests. Although attempts have been made to transcend the narrowing and limiting inertia of this form by expanding the scale of what workers could be included in a union—namely the movement for industrial unionism and its combination of the skilled and unskilled, black and white, foreign and citizen, man and woman—there has never been a trade union that amalgamated the entire working class into one organization.

Some modern unions, like SEIU, have come very close to being a general union in terms of the range of its workers’ occupations, but hardly a general union in any one firm or in any one industry or in any one region. The opposite has been the trend. Unions have fractured the most organized section of the working class into tens of thousands of shards across all these material divisions. We have seen our labor movement degenerate into a situation today where the unions spend much of their time fighting each other in small skirmishes and cold wars, rather than the employing class. Now is a time of intense particularity in the labor movement.

We will see what the future holds, but as socialists we must be prepared for one in which unions remain particular rather than general and in which we must continue to build a socialist movement and merge it with the wider labor movement, even if that labor movement has profound divisions and antagonisms within its industrial organization. In other words, we must have a socialist strategy that is operative even if the unions remain at odds with each other and sometimes even with the wider public. This is only possible if our strategy is one that imbues the leadership of the trade union movement with a spirit toward generality, what others have called a class struggle basis for unionism, a basis which sees fellow organized workers as autonomous and mutually respectable comrades and the mass of the unorganized as constituent human material no different than its own in any meaningful way.

This means a merger of socialist leadership into the leadership of the unions. This will be a leadership which coordinates itself and its own political program across all unions. In so doing, this leadership will rationalize the behavior of any individual unions against the strategy of a wider movement, for the benefit of all. In order to see this merger take place, socialists must throw themselves into struggle and imbue their ideas at every level of union leadership there is: root, stem, branch, and fruit.

Currently, the only accessible level of leadership to socialists is the absolute bottom of union leadership in any given union job or in the mass of the unorganized and ordinary workers. Even committee leadership and stewarding can have barriers to entry in some particularly broken unions. Of course there is always the barrier of the boss himself. So in order to open up the leadership of unions at every level, we must also reform these unions into organizations which do not prohibit the spreading of socialist ideas through our organizing and which do not discriminate or purge socialists who are coordinating across the entire movement. Despite being of a particularist form, it is possible to reform any union such that its structure will momentarily accept into itself a visionary socialist leadership. This is possible, and for a wider renewal of the labor movement, this is necessary.

That takes us to the question of union reform, a question socialists and non-socialists alike have tried to answer with increasing frustration for the past twenty years. So how do we rebuild our decaying unions? I argue, like many others, that we do so by getting ourselves organized as a political force—preferably a party but for now a proto-party— and into the leadership of the unions. However, I diverge widely from the dominant rank-and-file strategy in my attention as to how and where we accomplish this. I offer some concrete material trends and a review of union reform in this millennium to make my case.

My thesis in this series of articles is simple: when we built the labor movement before, we did it by organizing the unorganized. Why should we expect there to be any kind of movement in the workers’ movement if we keep placing preliminary reform steps between ourselves and setting to work on organizing the unorganized again?

All strategies for socialists to intervene in the labor movement have thus far failed to arrest the rapid disorganization of the working class and the labor movement in the United States now stands at its greatest crisis since the end of World War I. Tens of thousands of union leaders across this country are fighting like hell, yet every upsurge, every outburst, every glimmer of good news has fallen behind years of continued precipitous decline. In order to have hope, we must have a plan. In order to have a plan, we must have a strategy. Whatever strategy we pick must include room to imagine that, despite failure after failure for half a century, success is still possible as long as it has certain definite conditions.

This series will elaborate a new strategy for socialists in the labor movement which I have uncreatively named Reconstruction. It is exactly what it sounds like, and I will draw on four sources of success from past reform movements and synthesize them into a new strategy that is greater than the sum of its parts:

- Union entryism, past and present

- The worker-to-worker organizing model and examples as elaborated by Eric Blanc

- A proven successful type of union construction

- The republican ideal of social organization as it applies to union construction

I take as my motivation the same as that of Eric Blanc, when he writes in his new book:

An underestimation of today’s unique challenges has led more than a few advocates of militant grassroots organizing to rely too much on examples from the distant past and to be excessively vague about the means to build new unions today. Radical union writer Joe Burns, for example, has explicitly made a case for saying little about organizing methods, arguing that ‘left-wing trade unionism is not fundamentally about skills; it’s about putting trade unionism on a class struggle basis… Perhaps less organizing would be required if we actually had strategies that made sense to workers.’ Parallel to this vagueness about the nuts-and-bolts of union growth, leaders and activists grouped around Labor Notes have until recently focused more on transforming existing unions than on building new ones.[2]

I could not state the motivation behind my theorization of this new strategy any better than how Blanc puts it into words there.

To begin, our way of categorizing unions is hopelessly simple and lacks any real explanatory power to inform our strategy. Business, service, social movement, industrial, red—these each seem to indicate a general approach to unionism but say little about the structure and organization of power in the unions which are lumped in these categories. Are all business unions authoritarian and totally lacking democratic bodies? No, many of the building trades unions have more democratic control than the service unions. Are all service unions incapable of organizing workers outside of growth agreements? No, the nurses are primarily of a service model and yet can routinely organize and mobilize massive numbers of workers on contract campaigns and new growth fights. Do all social movement unions have a political strategy that consistently favors left-wing Democrats? No, some of the most “left” or “radical” social movement unions, which spend unbelievable amounts of their members’ money on their political programs, do so in support of libertarian and wrecker candidates for opportunistic reasons.[3]

In The Rank and File Strategy, Kim Moody references business unionism and its ideology over fifty times, tracing its roots from the post-Civil War walking jobsite delegate all the way to the late 1990s.[4] Moody several times contrasts business unionism with the Trade Union Education League (TUEL), the Congress of Industrial Organization’s (CIO) pre-war social unionism, and other foils. However, at no point in the pamphlet does Moody actually characterize what business unionism looks like in the contemporary period.

One can be certain that Moody believes business unionism is more inclined to engage in forever-bargaining in endless closed-room negotiations with the employer rather than taking immediate shop-floor action, like a strike. But beyond that general sense, it is impossible to say what Moody means by business unionism outside of the various context-sketches he provides. This is not at all helpful in the year 2025. Every union engages in collective bargaining. Every union has a grievance procedure. Every union has a voluntary political action fund and needs leaders to canvass the membership to raise the dues check-off rate. Every union makes temporary non-aggression compromises with employers. These legalistic and bureaucratic features of instantiating the union within the rest of civil society cannot be considered defining characteristics of business unionism. Neither can business unionism simply mean those unions which resort to these means more often than most unions do or those unions which resort to them more often than an arbitrary idealized type does.

Unfortunately, Moody’s is simply not clear as to what he’d have us do to unwind the destructive features of unions that are holding back worker militancy and class consciousness because the starting ground of play is too hazy and we begin thinking about unions and their structures in an unclear way. In order to know how a movement might strategize, we need a clear picture of that movement first.

This series of articles will construct a new labor reform strategy by addressing a number of issues. First, a new labor reform strategy necessitates a new typology of unions rooted in the actual organization of leadership that more clearly describes the differences in their structures and which has more explanatory power regarding union behavior and campaign outcomes. This is necessary for the moment since most labor literature relies on face-value readings of public communications by union leaders or theoretical guesses as to how the inner workings of unions actually run. This, I argue, has led our labor reform literature further from truth and utility. This new typology will be the primary subject of this initial installment.

Second, in order to deepen the socialist strategy for a new generation beyond Jane McAlevey and Joe Burns, it will be necessary to consult the latest evidence and observations coming out of new fights and new thinkers. Here we may rely more on Eric Blanc and the experience of organizing Amazon to think clearly about questions such as whether the teachers unions are still reformed, whether structure-based supermajority organizing in the McAlevey tradition ever really worked in an enduring, permanent sense, whether it is possible to return to CIO methods in the digital economy of small, distributed worksites. Similarly, we must contend with the fact that entryist strategies from the last few generations of socialist organizers, including, yes, even Shawn Fain’s tenure at the head of the UAW, have not produced significant gains in unionization among the unorganized. In order to fully understand the history of labor reform movements, I will return to each period of socialist reform strategy in light of the new categories and attempt to explain what part of the strategy or its implementation failed or did not take account of certain facts about workers and their unions.

Third, I will argue that the rank-and-file strategy as argued by Kim Moody could never have been a complete strategy and that the manner of its implementation by DSA will continue to bear no results until DSA is itself reorganized through campaigns along the lines of other labor tactics which could inform a more sophisticated and comprehensive strategy.

Fourth, I will review the latest serious proposal for the mass of socialist organizers, Eric Blanc’s take on a worker-to-worker model, which is rooted as much in observation and evidence as it is in a calculation about the reality of economic costs that are entailed by other organizing models.

Finally, I will construct a new strategy that considers all that came before and which identifies the most strategic points of intervention for socialist labor reformers and which gives proposals for both a type and model for organization of new union campaigns but also of socialist organizations which will need to create new organizing programs and leadership development pipelines.

The Boss Campaign Context

Before presenting my typology, we must make a short detour to discuss the most important structural obstacle to organizing a labor union: the boss as a free individual able to self-consciously campaign and strategize as much, or more so, than workers thanks to abundant economic resources. The boss is not an anarchic or unthinking structure. The boss is not “the superstructure” or “The Man.” The boss is the boss… or a handful of bosses delegated to make collective decisions on behalf of an even bigger boss. But in any case, from the owner-operator of a laundromat to the C-Suite of Google, there is someone in an office somewhere reviewing reports, reading memos, calling lawyers, asking questions to inferiors, jotting down notes, reviewing spreadsheets, in short, strategizing the most effective counter-campaign against the unionization of their workers. Somewhere in this person or people is a mind capable, yes, of creativity.

Too often, socialists in the labor movement unnecessarily muddy the facts by trying to evade this figure—the boss—by abstracting their decisions into a superstructure that cannot fully explain them all, or by presuming that whatever boss campaign there is will be predictable and uninteresting against the socialist organizer’s theories or prognostications. In other words, socialists perform a lazy kind of anti-boss inoculation by waving their hands at the boss’s intelligence, tactical acuity, and capacity for deception. This is wrong.

The DSP owners at Amazon, for example, are some of the trickiest campaigners I have ever encountered. They are ruthless, innovative, and unyielding in their insistence on defeating the union. The company has created a massive yawn of defensible space between themselves and litigation, and in many stations have given DSP owners many degrees of freedom to campaign independently within the scope of Amazon’s greater strategy. This has brought out the worst in boss campaign ingenuity, and Amazon is only one example.

The boss campaign in 2025 is not something to be waved away or trifled with. The boss campaign—or even just the fear of it—is the asymmetrical force that most often brings defeat upon worker organization. That is why every manner of union construction must have a crystallized form, what I will call “types,” a form that constantly sustains the legitimacy of its leadership and assuages the only truly universal tactic in any boss campaign strategy: third-partying.

From the beginning of trade unionism in the US as we understand it, there have been both organization campaigns by progressive workers and the reactions of bosses, which we will call counter-organization. From the earliest moments of organized labor, the public material of boss campaigns have always relied on the same premise, at minimum: that the union organizers, the leaders of the workers, whether from among them or not, are “outside agitators” who have a separate agenda or interests conflicting with those of the workers themselves.

It is sensible that the boss would reach for this among many other talking points. After all, the boss definitely has interests which conflict with those of the workers. To oversimplify a bit, every dollar a worker earns is a dollar less that a boss gets to keep. Workers inevitably discover the injustice of this arrangement after so long in an organizational campaign and become agitated against the boss on this fact. A true leader of the workers in such a campaign must share their interests completely. As the workers rise, so their leaders rise; as the workers fall, so their leaders fall. The only way for the boss to set the leaders of the workers and the leaders of the company on a level playing field in the workers’ collective imagination is to assert that, at bare minimum, just as the boss and the workers have an irreconcilable set of economic interests, so too do the union leaders and the workers.

This framing sets the situation up as a matter of comparison. Instead of workers directly confronted with the question, “will I follow my union leader to fight my boss for power?,” they must first answer the question, “which person whose interests I do not share do I respect more or would be more willing to follow, my boss or my union leader?” The former is a matter of overcoming personal fear, a matter of courage, a matter of the heart—a question that has one answer that leads to growth and improvement and another answer that leads to dilapidation and shame. Organizing a union is the human craft of getting as many co-workers to answer that first question the right way as possible. By contrast, the latter is more so a matter of weighing economic and social trade-offs, which reasonable people might answer in either way and which reasonable people may expect a net gain or a net loss for themselves and others depending on the context and balance of forces.

The famous Mohawk Valley Formula, written by James Rand Jr., the owner of the Remington Rand typewriter factories and who waged a complex Machiavellian boss campaign against his unionized workers in the late 1930s, has as its very first plank: “When a strike is threatened, label the union leaders as ‘agitators’ to discredit them with the public and their own followers.”[5]

The problem today of any one organizational campaign is the problem of defeating the boss campaign. The problem of unions taken generally is their failure to organize the unorganized—to crystallize structures into which leaders can be arranged and seem to routinely defeat the boss campaign, and to make these structures repeatable across time, space, and context so that they can be deployed to defeat the boss campaign anywhere within an economically feasible budget. This is the problem of private-sector labor organizing now, and this is a problem which socialists must also throw themselves into.

Union Construction and Organization

A new labor reform strategy necessitates a new typology that describes not only the tendencies and behaviors of unions but also their construction of leadership. In particular, the term “business unionism” has creeped far beyond its explanatory power and has become perhaps the least helpful term for understanding structural obstacles to organizing within unions. Rather than relying on the flawed heuristic of “business unionism,” I argue for a typology of five categories that frame the existing unions and their reproduction through both new organizing and maintaining existing organization. These five types are as follows:

- External-Bureaucratic

- Internal-Bureaucratic

- Separated-Powers

- Synthesized-Powers

- Spheres-of-Influence

As with any typology, there are no perfect real-world cases and many unions straddle the edge between two types.[6] However, I will not get rid of the old “model” categories altogether. Instead, I view these models as tendencies to resolve potential conflicts between the bureaucracy and officers, on the one hand, and the rank-and-file membership, on the other. Models describe the way this relationship is negotiated between the rank-and-file and their leaders. These models intersect with the new typology to give us a deeper understanding of union structure and behavior. I will set up four great models: service, business, organizing, and mass movement.

Each of these constructions is at once a manner of organizing power and leadership of a labor union. However, this manner of organization also entails both the provision and solution of the problem of third-partying. In other words, each of these types supplies an answer to: “Who will the boss say is the outside third party?” and “Why/How is that entity not really a third party?”

Each of these unions will train its staff organizers and worker leaders differently on how to talk about third-partying the union and in what manner they should reframe or resolve the problem of third-partying.

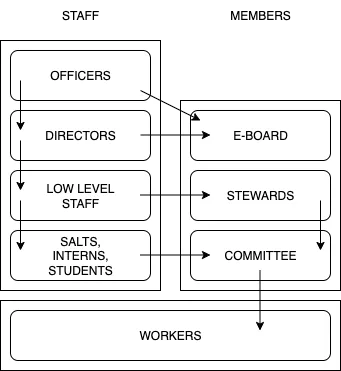

External-Bureaucratic

The external-bureaucratic union is one in which the locus of organizational power is found within a layer of staff bureaucrats drafted primarily from outside, or external, to the union’s rank-and-file membership. It is not only the provenance of these organizers but their current conditions that are external to those of the rank and file. In this type of union, the officers and staff have career ambitions, social groups, cultural valences, places of living, professional networks, and so on, all very distant from those that are typical of the rank and file. By having their interests and concerns set so far outside—external—to the rank and file membership, in addition to having been drafted from outside of it, and so, lacking even a memory of it, this union type finds that its leaders often respond more to concerns and interests external to the members.

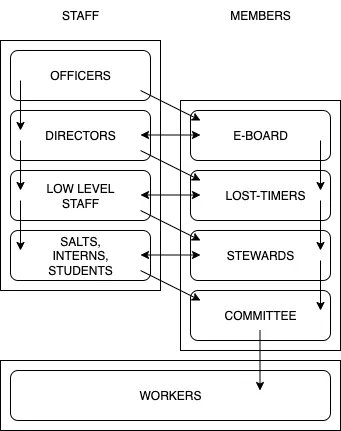

The external-bureaucratic union is not meaningfully organized and reorganized by democratic or deliberative bodies of members, such as member-only steering committees, executive boards, conventions, houses of delegates/representatives, etc. It is typical in this type of union that a group of staff directors makes decisions which are delegated to field staff on an ad hoc or intermittent basis. It is also typical in this kind of union that major organizational decisions are not made by the presidents or secretaries-general, with these serving as rather a more symbolic layer of leadership which may exclusively negotiate political or strategic relationships with important outside politicians or other key figures. It is at the level of the directors—sometimes making decisions by committee, other times independently over fiefdoms—where the real organizational power lies. In this sense, power is imposed onto the membership by a bureaucracy whose provenance is primarily external to the union itself.

These directors are mostly lifetime labor bureaucrats. Most of them, but not all, worked their way up to their directorship from starting positions as internal field representatives for a healthcare or service union. They were promoted by their predecessors and elevated largely on the basis of successful navigation of politics internal and exclusive to the union staff at this layer.

External-bureaucratic unions validate the boss campaign the most of any type. Because the directorship is so severed from the daily lives of the workers—by income level, education, race, geography, culture, employment background, and more—it is relatively easier than in the other types for the boss to find and develop anti-union leaders among the workers, who rightly begin from a posture of suspicion that the union leaders aren’t listening to them, aren’t responsive to their feedback, or don’t seek to elevate them to leadership equal with themselves. For the same reasons, the union leaders are less likely to correctly identify consensus campaign issues from among the workers. Even if they do know the workers’ local issues, they may have larger strategic campaign needs imposed on them which lead them to disregard those local issues.

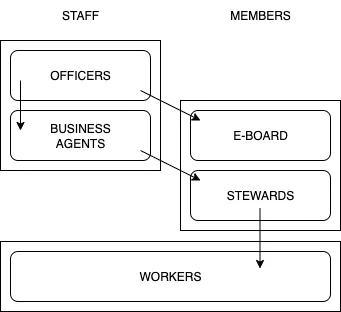

Internal-Bureaucratic

The internal-bureaucratic union is run by a layer of staff drawn mostly from—i.e. internal to—the rank and file membership. The staff layer is usually much smaller in headcount than the external-bureaucratic union. The internal-bureaucratic union has few deliberative or democratic bodies and those it does have carry little influence over the decisions of the executive leadership of the union. What we typically call business unions very often take on the character of this type. One key difference between the external-bureaucratic union and this internal-bureaucratic type is that either the secretary-treasurer or president, depending on the constitution or charter, carries much more power than the directors because that individual has wide latitude to control spending. This type tends to be the most authoritarian type of union, where the top leader of the local dictates ad hoc orders to directors of bargaining units or divisions who then do the same to their business agents or field representatives.

The typical president or secretary-treasurer of a union of this type started work in the industry and became a member, then became a steward or worksite leader, and finally was drafted onto staff full-time as a business agent. Elections for officers in these locals can be competitive, but dynasties are often set up that turn over leadership across an entire generation. Leaders of unions of this type often draw a large measure of their legitimacy from their experience in the rank and file over many years and stories of leadership from their time as member-leaders.

Internal-bureaucratic unions primarily validate third-partying through cronyism, corruption, and very strong aesthetic and cultural signifiers of in-group loyalty. Thanks to the closed shop, hiring hall, automatic growth, and high bargaining unit leverage of their workers, these unions do not need to invest in full structure coverage leadership within worksites in order to win contract fights, which means stewards are usually picked by business agents on the basis of loyalty, family ties, in-group identity, or cultural and racial background, rather than the objective spread of their leadership in the shop. These stewards can in many cases effectively serve to weed out junior, apprentice, or day labor from the hiring hall when they are out of step with the in-group status quo. This engenders the sense of unfairness within a plurality, if not an outright majority, of the membership in any given worksite, disincentivizes productive disagreement, and narrows the leadership development pipeline from the rank-and-file to a smaller, curated, and unrepresentative group of workers. Effective boss campaigns may portray these union leaders as aggressive thugs who are only interested in promoting friends and family to high-paid union offices.

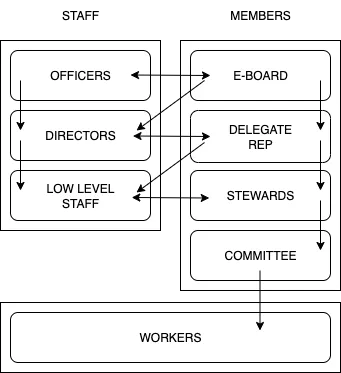

Separated-Powers

The separated-powers union is a union in which most major organizational decisions are made by collective deliberative bodies that are usually democratically elected. In this model, deliberative and executive powers are separated, normally on the basis of separating the functions of staff and membership; where members have direct routes to authority through elected bodies and staff through promotion within the bureaucracy. In this model, the membership strongly retains the power to set priorities and strategy, whereas the staff and officers strongly retain the power to execute and mobilize the membership toward the accomplishment of these goals.

On the less democratic end of the spectrum, these unions are those that have at least a robust convention every year and whose member-only executive board/steering committee is at least as influential as its staff directors. On the more democratic end of the spectrum, there are even some unions of this type which have strong and directly elected houses of representatives and/or delegates, boards of directors, and officers. These unions usually have powerful member leaders who work side-by-side in the organization of the union with staff directors. Normally, the president of this kind of union is also more than a symbolic office and which may have great influence over the organizational structure of the union. Because of strong democratic oversight over the budget, the secretary-treasurer or financial vice president, or equivalent, is not nearly as powerful of an office in this type of union as it is in the internal- and external-bureaucratic types.

The typical president of this kind of union began in the rank-and-file and ran for presidential office after having served terms on one of the elected governing boards. It is not typical—and in most cases not even possible—for unelected staff directors or field representatives to be able to run for president in a union like this. This is in major contradistinction to the internal- and external-bureaucratic types, where top leadership offices are usually captured by a business agent or field organizing director.

These unions are characterized by limits in scope of what the membership and the staff can do. Very differently from the internal- and external-bureaucratic unions, there are definite limits to the powers staff have in the separated-powers union. There is a whole scope of union business and leadership that is deliberately restricted to members. Members in these unions self-organize and can create their own leadership development conferences, retreats, programming, spending budgets, etc.

Separated-powers unions are the least vulnerable to third-partying campaigns by the boss thanks to their democratic structures and member-staff power-sharing arrangement. This type tends to produce union leaders who are most representative, on the whole, of the workers in their worksites.

Synthesized-Powers

The synthesized-powers union is the rarest type and may perhaps be defined by a single union: UNITE HERE. The synthesized-powers union is often misunderstood and mischaracterized as something like the external-bureaucratic type. This leads to explanatory errors, a mistake made famous by Jane McAlevey’s work, in which she ties together and somewhat equivocates SEIU and UNITE HERE under the same Saul Alinsky community organizing model, which she claims is staff-driven and suited only for mass mobilization, not deep and enduring organization.

The synthesized-powers type is one in which deliberative and executive functions are synthesized into the same body and where each member, staff, and officer is expected at varying times and contexts to engage in both deliberation and execution of plans, strategies, etc. The synthesized-powers union does not have strong democratic control by the membership. Conventions tend to be every other year, executive board members are hand-picked by staff directors, and most major strategic decisions are made, as in the external-bureaucratic model, at the level of directors, not by the membership bodies or the president. The key difference from the external-bureaucratic model is that these deliberative functions have not completely dissolved into toothless ceremonial bodies. Instead, deliberative and executive functions are fused, synthesized, in the fundamental unit of organization: the committee.

The synthesized-powers union is a structure of recursive, overlapping, and graduated committees. The model begins in the shop: a committee that is both representative and capable of mobilization is formed under a steward, who is identified as the leader by others. These committees are organized under a low-level staff organizer, who is himself a member of a team which operates as a committee under a lead. These leads are clustered together in departments as a committee under a director. The directorship is itself a committee.

The key organizational fact of this committee structure is that each committee at every layer is supposed to operate only on the basis of discipline: either all members agree to execute the committee’s plan with fidelity or no plan proceeds. This is a major distinction to all other types—the internal- and external-bureaucratic types find the staff operating individually, over fiefs, without substantial oversight, or by only the oversight of a single superior, such as a president or secretary-treasurer; the separated-powers model may operate on the basis of majority support for a campaign from its democratic controls, ie, 50%+1—none of these types require strict discipline or consensus to organize the way that the synthesized-powers type does.

The synthesized-powers union is also different from the external-bureaucratic union in that a substantial amount of staff leadership is drawn from the rank-and-file through leave-of-absence, internship, and volunteer organizing assignments. Many, sometimes up to half, of the directors and presidents are from the rank-and-file and for those who are not, there is an emphasis on hiring those who have tried to organize a union at their own worksite at some point in the past. This further dissolves the group boundary between staff and member leadership. This also differs widely from the separated-powers model, which tends to draw on the labor market pool of professional staff organizers, often, as in the case of the California Nurses Association and UTLA, trying to spend high and attract only “the best” organizers that these generous salaries can buy.

This model is as susceptible to third-partying as the external-bureaucratic type at first, but has several advantages to fight back thanks to more public-facing worker leadership on campaigns and the key organizational fact of committees campaigning by consensus, which ensures a unity between workers and staff that is more persuasive to undecided workers faced with a boss campaign.

In order to best distinguish between the synthesized-powers model and the external-bureaucratic model, it is worth analyzing McAlevey’s critique at length. Somewhat outrageously and with no supporting evidence, McAlavey claims in No Shortcuts that UNITE HERE’s organizers stand behind rank-and-file leaders pretending to be powerless bureaucrats, but in fact make all the decisions and, I suppose, actuate their members like puppets to pass staff decisions off as member-inspired.

I do not deny that this kind of thing happens in all unions, including great organizing unions with powerful leaders who are also capable people in their own lives: nurses, teachers, firefighters, electricians. Lazy and bureaucratic staff who do not understand how to recruit, retain, and develop real leaders of unions are endemic to the labor movement. McAlevey seems to specifically identify this problem with SEIU and UNITE HERE and roots it in the intellectual inspiration of Saul Alinsky on a generation of college-educated organizers that joined the staff of these unions in the 1970s. She quotes SEIU 1199NE’s longtime leader Jerry Brown:

I never heard anyone use Alinsky in any way as a model for us. He was always talked about only in the context of community organizing, and how their organizers always had to be behind the curtain—their job wasn’t to speak publicly, their job was to find and recruit. [The union that] came closest to this was HERE (the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union), because they always had rank-and-file officers who appeared to be the leaders. The rank-and-file officers were often wonderful union members who put a lot of work into the union, but they were very seldom the real, strategic leaders. I thought the 1199 model, with all its troubles with staff being members and sharing leadership, not just facilitating recruitment, it was 100 percent more honest to what was going on, and actually who was really leading. I just always felt that the way in which HERE actually led, and the way in which it appeared they led, were very different realities.[7]

It would perhaps shock McAlevey to find out that a definite component stressed constantly to young staff in UNITE HERE is that they are real leaders, with real responsibilities, and with a plan for their development to make them as much as they can possibly be, just as there is for each member. The key to synthesizing executive and deliberative functions in this type of union is to place the burden of growth, development, leadership, and intelligence on everyone. No one serves only the deliberative function, where someone else serves only the executive function. Staff make real leadership decisions, and members spearhead real mobilizations to execute those decisions. And vice versa: members who step up to take leadership make real decisions and delegate their implementation to staff.

Across the country, members directly out of the rank-and-file of UNITE HERE who were not salts but organic leaders discovered in the course of campaigns have fought their way up into directorships of the staff of large locals, often starting out their career unable to even speak English and without documentation to live in this country legally. It is insulting to these very real leaders to presuppose some other director—probably white, probably a man, probably highly educated—is actually undermining these leaders and feeding them decisions, because, although they are “wonderful,” they just aren’t capable of forging their own path.

Later on, McAlevey claims, “the full-time staff of most of these groups said, ‘Leaders make the decisions, we just implement them’—a claim still made today by SEIU, UNITE-HERE, and many other unions. Clawson points out that SEIU and UNITE-HERE made a conscious decision to hire from outside their ranks starting in this same era, the 1970s, which was atypical.”[8]

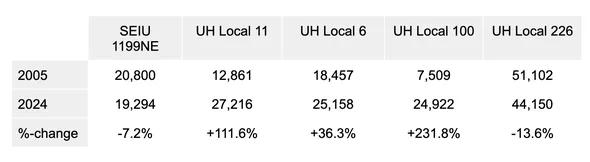

She goes on to unfavorably compare HERE to 1199NE on every point, claiming that HERE doesn’t organize supermajority participation strikes often enough or considers strikes merely symbolic, that it uses card check to build paper membership, and so on. Well, to put a final point in McAlevey’s mistake about the nature and success rate of the type of union UNITE HERE is, see the membership data for 1199NE next to the four largest UNITE HERE locals over the past twenty years through not one but two major shutdowns and recessions in the hospitality industry, while healthcare profits and employment have soared.

Although Culinary 226’s membership has declined on net, it must be noted that membership is tightly correlated with the hospitality business cycle, and it was recently announced that the casinos on the Las Vegas Strip are now at 100% union density under Culinary 226 contracts. With over 95% of represented workers choosing to opt-in for membership in an anti-worker, right-to-work state, this represents an unheard-of industrial victory.[9]

These locals managed to grow through the most damaging raid of the twenty-first century US labor movement simultaneous with a recession in 2008-9 that wiped out 220,000 (47.9%) of the international’s members, and another 165,590 members (53.8%) again in 2020 due to COVID-19 shut-downs of the hospitality sector. And yet, just five short years after the last of these calamities, the union is back up to about 300,000 members, the highest level since 2008. Meanwhile, Local 11 took on the largest coordinated hotel strike in US history in 2023 in southern California that involved about 15,000 hotel workers out of contract.

In contrast, as of 2024, there are 41,230 home care workers, 1199NE’s jurisdiction, making a median wage of $16.92 in cozy liberal Connecticut, which has the fourth highest unionization rate in the country and the highest for public-sector workers.[10]

It is very easy to back-interpret and over-estimate the influence of a single key person—in this case, Saul Alinsky—but this is precisely why I am preparing this new typology. I believe lazy, unclear, and simply factually wrong assertions about how our existing unions are organized continue to proliferate throughout the labor movement, and often from its most prestigious minds. Explanations that cast types onto unions based purely off the influence of one person, which look backward in time for models in the CIO or the TUEL, which hold the public statements of union leaders up against a rubric, or which have reasoned backward from an ideological predestination—all of these simply fail to describe how contemporary unions actually work and what about their structures makes their campaigns either routinely succeed or fail.

Spheres-of-Influence

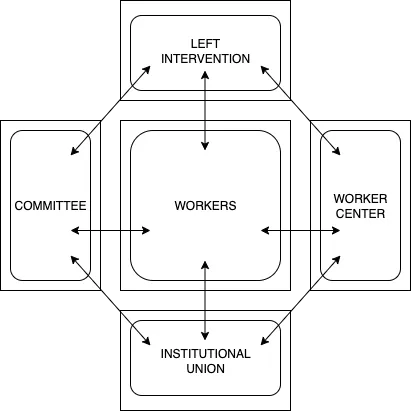

The spheres-of-influence union is exclusive to new worker organizing contexts and is the most unstable construction of all types. The “spheres of influence” in question reflect a mosaic of communities under disparate leadership all united by one and only one goal, unionization of a worksite.

In some new organizing contexts in this country presently, this mosaic looks like worker centers, nonprofit groups, charities, university solidarity groups, socialist organizations, one or two major institutional unions, and an organic worker leadership. Many unions which employ a “comprehensive campaign” strategy, such as UNITE HERE, might draft this kind of a mosaic into a given union campaign, but retain fundamental strategic and organizational control over workers in the shop. The spheres-of-influence type differs from these campaigns in that leadership truly is divided and must be consolidated through treaty/agreement of authority granted largely by the shop floor.

This type of union usually describes the arrangement of power in extremely low-wage organizing contexts, such as immigrant day labor organizing, ethnic neighborhood community organizing, fast food organizing, the organization of the working homeless, and so on.

The spheres-of-influence type is the most difficult to define and identify, as unions of this type test the boundary between organization and disorganization. Campaigns rise and fall within the scope of weeks or months, rather than years. The balance of forces and institutions shift and change, with players entering and exiting the union campaign frequently. This is also the type that predominates in extremely high-turnover industries where the worker leadership is constantly changing. For precisely these reasons, this type of union is fairly difficult for the boss to third-party. The closest institutional union to the campaign or primary financier will be identified as the third party.

Organizational Models

It does not automatically follow from the type of a union’s construction what its organizational model will be. By “organizational model,” I refer to the relationship negotiated between the rank-and-file and its leadership in the form of staff and officers. Even if a union is constructed in the external-bureaucratic type, for example, that does not mean it will never organize its rank and file membership. Sometimes, an external-bureaucratic type is even capable of deep and mass organization. Yet it remains an external-bureaucratic type due to the locus of power in the union and from where that power derives its authority.

The four great models of organization in US unions are: service, business, organizing, and mass movement. I will review what defines each of these models.

Service—this is an organizational model in which the rank-and-file membership of the union relates to its leadership primarily through services. Members of these unions think of their leadership as primarily the mediators by which these services can be provided.

Business—this is an organizational model in which the rank-and-file membership of the union relates to its leadership very infrequently or not at all. Union leaders negotiate growth and contracts primarily without member knowledge or participation. Stewards are appointed by business agents or field representatives, but most shops do not have any. Structured participation in the life of the union is virtually absent.

Organizing—this is an organizational model in which the rank-and-file membership of the union relates to its leadership through voluntary participation and an obligation to lead when needed. Union leaders spend lots of time with rank-and-file members, talking to them and trying to persuade them to participate, follow, or lead in their union.

Mass Movement—this is an organizational model in which the rank-and-file membership display a high degree of self-initiative toward mobilization and do not wait for formal leadership to engage in mass action. This model predominated in the 1930s but is rare in the twenty-first century and primarily, though not exclusively, mediated through mass digital communication.

It would be generally true to say that the construction of the union is imposed from the top down whereas the organizational model grows from the bottom up. Whereas union reform movements of the past have sought to capture the top echelon of leadership, usually the officer and board seats, some of these movements have assumed that the reorganization of the union at the bottom will happen as a matter of course after staffing changes, reorganization of worksite leadership structures, or even changes to the constitution and bylaws of the union. This is not the case. Bottom-up reform requires altering the organizational model, which after years of conditioning by former generations of leadership, may be hard-wired into the rank-and-file shop leaders in the form of learned helplessness, expecting services on-demand, lack of trust in their own members, inexperience with the logistics of large mobilizations, etc.

To truly reform a union, the type of construction must be changed first, but there must also be radical changes brought upon the grassroots of leadership in the rank-and-file. This change of model cannot be imposed by newly hired staff organizers, as this is both expensive and risky given that most internal field representative staff organizers are unfamiliar with an organizational model and more often reproduce service and business models they learned at other unions, not to mention that imposition by staff jeopardizes the reform movement in the first place by threatening the reestablishment of an external-bureaucratic type. Instead, the bottom-up remodeling must be patterned by the workers who have taken reform leadership themselves, and that means more member-to-member organizing and an effort to build structures directly connecting rank-and-file local leadership with the top officers.

The Organizational Limits of Each Type

Under capitalism, it is the goal of any good union leader to organize workers to strike against the employer. The benchmark of success for a strike is precisely the degree to which production ends and thus the degree to which profits are lost. In a theoretically frictionless context, we might assume that a union has a 100% success rate in its organization which results in 100% of workers walking off the job indefinitely. The boss in this scenario could then attempt to replace 100% of those workers with scabs from the world outside the firm. At which time, the union, which is 100% effective, would then organize all 100% of those scabs not to cross the line. The employer then would find another group of scabs and the union would organize them not to work, either. So on and so forth, and it would appear this perfect, powerful union would keep production 100% shut down. The settlement of victory in this case may be total ownership of the firm, in our perfect world.

Anything less successful than these conditions means that production continues but at a reduced rate or at a higher cost to the employer. In the real world of strikes, the operating philosophy for a union organizing a strike is simply to maximize this cost or minimize this rate of production, or both, which will result in maximal economic damage to the employer and, thus, the most favorable terms of settlement for the workers to return to work.

Now let us assume that the degree to which production is slowed down or made more costly is a function of the balance of persuasion over the workers as between the campaign of the union and the campaign of the boss—and let us assume for a moment that it is only a function of this balance. In this world, a 0% effective boss campaign and a 100% effective union campaign would result in a 100% walkout and a 100% stop to production. Perhaps a 25% effective boss campaign and a 100% effective union campaign would result in a 75% walkout. A 50% effective boss campaign and a 50% effective union campaign may result in a 25% walkout. It is not important in this theoretical construction what the function might be, just that there is some relationship between the effectiveness of the boss campaign, the effectiveness of the union campaign, and the level of success of the mobilization of workers to strike—a headcount on who is out of the shop and on the picket line.

We have established that the primary campaign tactic of the boss, and the only fundamental campaign tactic the boss can resort to if all others fail, is the third-partying of the union—there are many others, but let us only consider the universal one for the sake of making an argument. We have also reviewed our different types of unions and made a note about how much vulnerability they have to being third-partied by the boss. Now let us bring in our types of unions to this theoretical strike and ask ourselves the question—for each type of union, what level of effectiveness of the boss campaign do the unions give away for free, so to speak, by virtue of their structure of leadership?

A perfect, general, voluntary union—perhaps the ideal union construction imagined by the early Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—would be a union that springs up entirely organically, one which is not sewn by more conscious elements, outside organizers, institutional bureaucrats, intellectuals, etc. This is a union where by dint of enlightenment ex nihilo, the organic indigenous leaders of the workers in a worksite realize the injustice of how they relate to production, awaken, and begin to organize those they lead to take immediate action to shut down production. This union gives exactly nothing away to the boss campaign. Lacking outside agitators, union staff, intellectuals from the city, members of other unions in the same industry, religious zealots, or any other outside factor whatsoever, this kind of union could not be said to be anything but equivalent to the movement of struggle of the workers themselves, on their own, to take production away from the boss. This type of union, which does not exist, may be more or less effective in its own positive campaign, but we can say that it certainly gives away 0% effectiveness to the boss campaign, since no component of its structure is vulnerable to accusations of third-partying and its behavior would not validate the claims of third-partying.

To the other theoretical extreme, we can imagine a mandatory, specific, involuntary union—in this union, only a subset of the most skilled workers are eligible for membership; failure to pay or failure to cooperate with the bureaucracy that collects dues results in death by beating, so this is also a maximally coercive power structure; exactly one person, who neither works with the members nor even in the same industry or city, decides the pace of struggle and the terms of settlement with the employer; and finally, there is no mechanism for members to intervene in this situation. This is a union which we might say fully validates the third-partying claims of the boss campaign, in other words, it gives away 100% of the effectiveness to the boss campaign that it could possibly give away.

All of the types of real unions described in the typology of the previous section, in reality, give away some effectiveness to the boss campaign, to a degree somewhere between the two theoretical unions described above. Indeed, some give away more and others less.

If it is still unclear that unions routinely give away effectiveness to the boss campaign, consider the following illustrations of third-partying in the most common union scenarios that are happening by the thousands on the day that I write this:

I can’t help you with this grievance if you don’t bring me good documentation and evidence.

This is third-partying because it removes the locus of control of struggle from the worker. The worker becomes a field secretary for the staff, yet an individual grievance in most cases is a contract violation against just one member. Training the member to see themselves as someone who is merely there to help someone else fight for them, rather than challenging them to fight for themselves, is a form of third-partying the union into a staff bureaucracy.

The rewrite:

In our meeting with management, I think you might embarrass yourself if you don’t have the evidence you need to make your case. What do you think this grievance is missing?

This implies everything—gathering evidence and making one’s own case in a step meeting—is going to be handled by the member. This new framing will challenge them to develop their leadership.

Life is better when you join the Teamsters.

The construction of new unions is not a matter of “joining” an existing union, but of struggling to organize new workers for the establishment of an entirely new organization. Although existing institutional unions may lend financial and organizing support to unionizing workers, their framing that support as primarily joining or growing the existing union is a form of automatic third-partying.

The rewrite:

Life is better when you and your coworkers are organized to make it better. What can the Teamsters do to help you succeed in building your union so that it’s as strong as it can possibly be?

This implies that the union is in the hands of the leadership of the workers and that there will be a process of construction which they control and direct, while also emphasizing the superiority of union organization and being clear that Teamsters will also be helping that process along.

You want to have a contract. You want to have the benefits of representation.

The collective bargaining agreement is not something anyone owns. It is a statement of what should be the militancy of workers and their degree of organization crystallized in three or five year increments of time and the documentation of the ideal terms of a mutually agreed non-aggression between workers and their management. The expectation is for the employer to violate almost all of those terms for the period of the contract, which this statement obfuscates by implying ownership or possession of a copy of the contract somehow makes its provisions real in effect.

The rewrite:

You want to fight so well that you get everything you want, and whatever contract you win should reflect that. What would happen to you if you left the quality of your job entirely in the hands of your boss?

This rewrite captures the fact that contracts are merely a symbolic representation of terms of employment that have been actually secured through struggle.

All three of these examples are routinely heard in campaigns and framed as good, proactive organizing by most union staff. Yet all three of these organizing lines destroy worker leadership and hand free victories away to the boss. While the journey of these messages across the workforce and the general understanding of the workers in a worksite of what their union is may be complex, all forms of third-partying ultimately add up to giving away tactical advantages to the boss campaign.

Returning to our theoretical strike campaign, we can imagine that some unions probably produce organizing claims like the following more often than others:

If we don’t strike, we can’t get a good contract.

Once we win the strike, we can get back to dealing with grievances for our local issues.

Striking is the only way for us to get more money.

All three of these, perhaps to the reader’s surprise, are also flippantly third-partying the union. The first sets the goal of a strike as a contract—the opposite is the case; the goal of a strike is to build organization to the extent that it can routinely and permanently strike to end production and cost the boss as much in lost profits as possible. Strikes should build organization, not expend it. Good strikes construct the union. The contract is a reflection of the power the union builds, not its object or end-goal.

As to the second, it frames the building of organization as a necessary obstacle to engaging in a representational process that is less effective at solving problems than the strike itself.

The third is a slightly more subtle restatement of the first.

More sophisticated and worker-leader oriented field organizing programs that have internalized the danger of third-partying will simply try to bypass the issue by training their staff organizers to basically refuse to make declarative statements and instead rely on so-called “hard organizing questions.” This method is slightly better, as it deliberately leaves space for workers to conjure solutions to their own problems, but it does not solve the third-partying problem unless the questions themselves aren’t also free of third-partying in their premises. Consider the following questions:

How do you expect to be able to afford to live in California if you don’t strike?

What will it take for this strike to win a fantastic contract?

What do you think your life will look like by [insert projected end of next contract cycle] if you don’t strike?

At this point, our organizing questions are starting to reflect what you might hear at the best, most dynamic organizing unions. However, think for a moment about the premises underlying each of these questions and whether or not each third-parties the power of the workers into some form of bureaucracy beyond their control or a symbolic gesture toward power that is supposed to reflect, but not literally is, power itself. Put simply, do these questions necessarily lead a worker to understand that their power is the power to end production and that anything else is an epiphenomenal consequence of that power, a written artifact of it? They do not. Instead, each of these questions assumes the premise that the strike has an object or an end that is material.

Of course, strikes result in great contracts and more money to the degree that they are effective. No one disputes this. But questions that presume an endstate if the worker is to strike are questions that actually do project a definite cause-and-effect into the future—this must be avoided at every juncture of a campaign. Strikes do not always lead to keeping up with the cost of living. Strikes do not always lead to a fantastic contract. Strikes do not always lead to a better life.

The readers should now see that the preponderance of organizing in the labor movement is actually being done along premises that third-party the union severely with even what seem like the most thoughtful questions. The actual best organizing questions for a strike:

What will happen if every single one of you strikes?

What will it take to get every single one of you to strike?

What kind of person will you see yourself as if you can get all your coworkers to strike?

These questions inevitably get one response from workers the first time they are asked: “I can’t answer that because that isn’t possible.” Aha! So we have finally hit the root impediment in the union campaign, a much more productive answer than one will get from any of the other questions offered above. No strike will ever stop production if the leaders don’t believe it is even possible. Any good union leader knows that this is possible. A failure to imagine the possibility that a strike could completely succeed moves hand-in-hand with the implied belief that a strike is merely symbolic, one of the most dangerous and destructive ideas floating around the contemporary labor movement.

So, what are the propensities for each type-model of union to produce these kinds of strategic liabilities, these free gifts to the boss campaign? The external-bureaucratic business union is the most likely and the separated-powers mass-movement union is the least likely. The latter exists in trivially few places in this country, possibly only Starbucks Workers United (SBWU) and the UE’s graduate student drives, which I will elaborate on further in a subsequent installment. Every other type-model fares somewhere in between when it comes to handing away free third-partying liabilities to the boss campaign, but generally speaking the most consistent and consistently successful type-model is the synthesized-powers-organizing union, which tends to produce a steady growth of well-organized new workers and can strike its internal membership at regular intervals and at supermajority levels of participation when needed.

The reader must accept that it is impossible to find any real or useful data about the frequency of unforced third-partying by leaders in organizing campaigns. We are discussing the absolute roots of the human connections that make up labor organizing and, in general, these things are near-impossible to study on-site due to the lack of interest, lack of funding, highly secretive nature of new organizing campaigns, and, most frustratingly of all, a lack of new union campaigns even happening, all of which have contributed to my very real motivation to construct this typology. But alas—the reader must take much of what I say on trust alone when it comes to this portion of my argument. These assertions are not based on an anecdotal few of my own organizing conversations—but on both my own and dozens of other organizers’ conversations across five different unions of different types, good and bad, in multiple languages, with hundreds of workers across all walks of life.

I believe this typology is much more helpful than the hazy distinctions we have been making between social movement, business, and service unionism. It captures many more aspects of how power actually works in a labor movement split between the voluntary leadership of workers and a massive army of college-educated, lifelong staff bureaucrats. I believe this typology, presented in light of the boss campaign, also helps illuminate why some unions simply cannot organize new workers at scale with their current structure. I welcome readers to respond with counterexamples and/or elaborations on this typology. Having laid out these new categories, my next installment will review the various periods of labor reform movements, the many ideas proposed for socialist union organizers, and make arguments about why these have failed to arrest the decline in unionization or spur on new worker organizing.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Bryan Palmer, Revolutionary Teamsters: The Minneapolis Truckers’ Strikes of 1934 (Brill, 2013), 71-72.

↩ -

Eric Blanc, We Are the Union: How Worker-to-Worker Organizing Is Revitalizing Labor and Winning Big (University of California Press, 2025), 48.

↩ -

For instance, AFSCME 3299’s recent $1 million expenditure to unseat Josh Newman in the California Senate in favor of one of the most labor-hostile politicians in California. See: Ryan Sabalow, “California Senate leader calls union ‘morally bankrupt’ for opposing a vulnerable Democrat,” Calmatters, November 13, 2024, https://calmatters.org/politics/2024/11/afscme-against-california-democrat/.

↩ -

Kim Moody, “The Rank and File Strategy: Building A Socialist Movement in the U.S.,” https://solidarity-us.org/rankandfilestrategy/.

↩ -

Benjamin Stolberg, “Vigilantism, 1937,” The Nation, August 14, 1937, https://web.archive.org/web/20090720035040/http://newdeal.feri.org/nation/na37145p166.htm.

↩ -

For example, the California Nurses Association has some internal structures, such as a large, outside-hired non-nurse organizing staff that makes most of the organizational leadership decisions instead of members, that fit the type-character of external-bureaucratic while other structures, such as its dynamic, nurse-driven new organizing campaigns more fit the synthesized-powers model.

↩ -

Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing For Power in the New Golden Age (Oxford University Press, 2016), 46-47.

↩ -

Ibid, 49.

↩ -

Rio Yamat, “All major Las Vegas Strip casinos are unionized, defying national trend,” Associated Press, August 4, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/las-vegas-strip-culinary-union-casinos-hotels-804fafe363e0bc593084ab17531b2e25.

↩ -

“Healthcare Support Occupations -Statewide 1Q 2023,” https://www1.ctdol.state.ct.us/lmi/wages/statewide2023.asp#healthcaresupport.

↩