The latest global capitalist meltdown appears to be underway—quite possibly the most destructive yet and one from which capitalism will never recover, necessitating an unprecedented struggle for human liberation and world socialism; a publicly owned economy on a worldwide scale.

US unemployment has been ticking upwards for the past two years and, after the worst October in two decades, job losses have already hit 1.2 million in the first eleven months of 2025, up by 54% year-on-year. (The number of jobs created from April 2024 to March 2025 has also been revised down by 911,000.) Job cuts have surpassed one million in a single year only five other times since 1993: in 2001, 2002, and 2003 when the dot-com bubble burst; 2009, during the housing market crash and Great Financial Crisis (GFC); and in 2020, when the COVID pandemic and lockdowns struck (following flatlining growth in 2019). The federal government leads the way with 300,000 job losses, followed by the technology sector (100,000), warehousing, retail, and services. Average time spent out of work has also hit twenty-four weeks, up from sixteen weeks before the GFC.

The beginning of a recession is unlikely to be officially confirmed until a year after it starts, but a wide range of economic data signals a brewing crisis. According to Moody’s Analytics, twenty-two US states and the District of Columbia have experienced shrinking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) this year and another thirteen have flatlined, leaving only sixteen generating or experiencing growth.

The Institute for Supply Management manufacturing index indicated a contraction in the US manufacturing sector for eight consecutive months up to the end of October, putting the index at 48.7, a figure strongly associated with an economy-wide recession. In fact, the index has only expanded in two months out of the past thirty-six.

Housing starts in the US are expected to come in at 1.3 million this year, having dropped from 1.6 million in 2021 to 1.55m in 2022, 1.42 in 2023, and 1.36m in 2024. In August, the delinquency rate of office mortgages packaged into commercial mortgage-backed securities jumped to 11.7%, surpassing the 2008 peak of 10.7%. As recently as December 2022, the rate stood at only 1.6%.

Some 67% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, up from 63% in 2024 (PNC Bank)—spending their entire income on bills and expenses as it comes in, leaving little to no money for savings or emergencies.

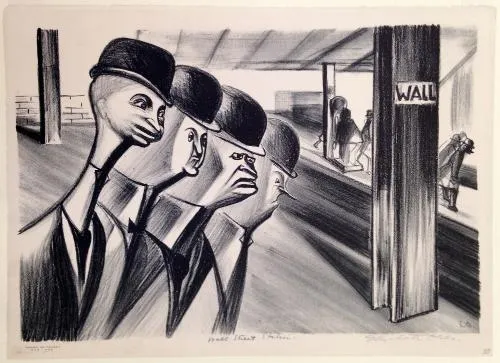

Glorified Betting

Desperate not to spook investors, multinational investment bank Goldman Sachs contended in October that “anticipated investment returns are sustainable.” In just the past three years the value of the S&P 500 has doubled—putting it at 179% of GDP—something that took twenty years from 1965-85; or seventeen in 1997-2014. The wider Wilshere 5000 is at a record high of 224% of GDP, beating the 193% of December 2021 and 135% of March 2000. The total volume of options traded (betting on price moves) has hit $3.5 trillion per day, a six-fold increase since 2020.

A stock market frenzy, however, is itself a bellwether of a weakening real economy, since a shortage of profitable opportunities in commodity production—where new value is created—is chucked instead into the glorified betting of speculation, inflating the value of stocks and generating a false sense of prosperity. From the start of October to mid-November, furthermore, only 38% of S&P 500 stocks trended upwards (risk-taking expands at 66%). Michael Burry, of The Big Short fame has, as he did back in 2008—when he made millions of dollars by betting against the mortgage market—deregistered his hedge fund.

Many commentators and analysts sounding the alarm are drawing comparisons to 2008 and 1929. The situation might well be worse than either. At the end of 2024, US banks had about $483bn of unrealized losses on their securities; compared to no more than $150bn in the run up to the GFC.

The concentration of stocks and general wealth in the US is now on a par with the late 1920s, for the first time since that dark period. The population’s richest 10% of households own 93% of the stock market’s value. The top twenty-five stocks account for 45% of the S&P 500 and the top seven for 31%. Nvidia's market cap is 7% of all 3,265 publicly-traded US companies.

But only 10% of households were invested in the stock market when it crashed in 1929—now 62% of US adults report owning stocks, and that's not counting retirement funds that are often directly or indirectly invested in the stock market. At least 43% of retail investors (individuals) are buying more stock than their cash can afford. The US economy is the stock market and, at an all-time high, it's highly leveraged.

In the run up to the Great Depression, all active home mortgages represented 10% of the US’ GDP, rising to 32% in 1930. US mortgage debt today is 70% of GDP, more than $18 trillion in total household debt. (In Australia and Canada, mortgage debt is higher than the country's entire GDP.)

The rapid expansion of margin debt, the total amount that investors have borrowed to buy securities—which fuelled the 1929 crisis—reached a record high of $1.1 trillion in September, up by 34% on 2024. The private (non-bank) credit market is exploding at a rate of around 15% a year, rising from $0.5 trillion back in 2012. Drawing comparisons to the 2008 subprime housing crisis, US subprime used-car lender Tricolor filed for bankruptcy in September after it allegedly pledged the same loan portfolios to multiple lenders, exposing private credit providers and major banks such as JPMorgan, Barclays, and Fifth Third to unexpected losses, with its filing listing up to $10bn in assets and liabilities.

‘AI’ Bubble

The private credit bubble is only a part of a much larger one—an ‘everything bubble’ that since the GFC has for the first time ever engulfed every asset class. Now the ‘AI bubble’ has joined the party and outbloated all that came before. The top ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks are all tech sector stocks, and the tech and ‘AI’ sector accounted for a scarcely believable 92% of US growth in the first half of 2025. Since the debut of the advanced research assistant tool ChatGPT in November 2022, AI-related stocks have added an estimated $17.5 trillion in market value—75% of the S&P 500’s gains.

In breakneck competition to construct expansive data centers equipped with specialised, cutting edge chips, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta reported a combined capital expenditure of $245bn in 2024, a figure expected to surpass $360bn this year. According to an MIT report, though, only 5% of integrated AI tools are generating profitable returns.

In the third quarter, venture capital deals with private AI firms dropped by 22% quarter-on-quarter. Amid ongoing problems with reliability and the rocketing costs of training new models, furthermore, AI-tool usage at firms with more than 250 employees dropped from nearly 14% in June to under 12% in August. According to Edge AI & Vision Alliance, training costs have surged by more than 4,300% since 2020, driven mostly by the rising price of chips and staff (engineers and researchers).

Investment has been pouring into AI stocks out of lack of other options. Oracle’s debt-to-equity ratio is 500%. Chat-GPT owner OpenAI is valued at $500bn but reported a net loss of $13.5bn on $4.3 billion in revenue in the first half of 2025. The company does not expect to be profitable until the end of the decade and is now begging tail-between-legs for a government bailout. Such talk at the start of November sent the NASDAQ down by more than 1% in a single day and wiped $1 trillion off the value of Wall Street's most valuable tech companies within a week.

Bain & Co. estimates that cloud service providers like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon will have to generate an additional $2 trillion in annual revenue by 2030 to afford all the necessary infrastructure—five times more than the current global market for software subscriptions. In 2024 Amazon, Alphabet, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and Nvidia combined made less than $2 trillion.

The capitalist state is already riding to the rescue. The 2024 AI National Security Memorandum recast the success of US AI as the national security priority of our times. The Trump administration’s AI Action Plan aims to accelerate AI adoption within the government and military by pushing changes to regulatory and procurement processes. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act authorised $1 billion in AI funding, and the administration says more loans, grants, and tax incentives for AI infrastructure will shortly follow.

These subsidies and bailouts heap yet more debt onto the back of a public increasingly weighed down by the burden of saving the private sector continuously since 2008.

Nvidia, OpenAI, and major data center operators are propping up one another’s growth through large, incestuous circular investments. As demand far outstrips the supply, Nvidia sells its chips (which it designs but are actually manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) at an extremely high margin. It is left with little choice but to subsidise that demand by investing in AI firms that then purchase its hardware. OpenAI has committed to buying 10 gigawatts of compute from Nvidia, at a cost at least $15bn each; but in return Nvidia is investing $100 bn in OpenAI (for non-voting shares). Similar arrangements run through other firms like CoreWeave and Nebius.

As profitability falls, liquidity reserves and lending dry up, and job losses rise, the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, is tentatively lowering its baseline interest rate to encourage banks to transfer their reserves onto the market (at higher rates)—fueling the bubble.

If an ‘external’ factor doesn’t spook investors first, the intensifying concentration of stocks will eventually shut out too many of them from returns and a massive sell off will begin, bursting the bubble, which will also happen if a panic-sparking absolute economic contraction sets in. The fictitious ‘money’ investors have been throwing into this hole will be wiped off the ledger board. A 30% correction is strongly correlated with an economy-wide recession, but a much higher figure, perhaps accumulated over the course of two or more ‘corrections,’ should come as no surprise.

Gita Gopinath, former chief economist of the IMF and now with Harvard, believes that a market correction of the same magnitude of the dot-com crash—when the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ Composite crashed by 50% and 75%, respectively—could wipe out about $20 trillion in wealth for US households, nearly 70% of annual US GDP. On that basis, consumption would fall by more than 3% and GDP by two percentage points, easily enough to push the US economy into a deep recession. She also estimates that foreign investors could face wealth losses exceeding $15 trillion, about 20% of the rest of the world’s annual GDP, since US equities make up 60% of the global market. We should not be surprised if Gopinath’s estimate turns out to be wildly conservative.

1929

In contrast with the asset inflation that characterized the aftermath of 2009 and the asset and consumer price inflation after 2020, 1929 resulted in absolute overall deflation, which the Fed is desperate to avoid, since money loses its value faster relative to debt and demand falls faster in anticipation of falling prices. The Wall Street Crash impacted the whole world so badly because the US, then a net lender, was the world’s biggest lender. The rest of the world needed to borrow US capital to grow their economies.

As the home of the world’s dominant reserve currency and richest consumer base, a US collapse today will again of course shock the whole world. Now, though, the US is a net borrower and the largest borrower in the world. About 25% of its government spending is financed by foreign capital inflows, but the appeal of the devaluing US dollar appears to be waning. At the end of 2024, China’s US Treasury holdings were $759bn, down from $1.07 trillion four years earlier. The figure for Japan is down from $1.3 trillion to $1.1 trillion. As a share of global reserves, the greenback has fallen to 56% from 73% in 2000.

Since 2020, official US government debt-to-GDP has been higher than the 119% at the end of WWII. On course to soon hit $40 trillion, US government debt is growing at around 6% per year and the annual government deficit (since 2008) 8.5%. As the debt rises, the risk of lending to the government climbs as the chances of the overstretched tax base losing its capacity to repay (and with interest) therefore naturally increases. Lenders therefore tend to demand higher rates, further undermining their own investment as the government is forced to increase its borrowing to cover the difference, expanding the money supply and fueling inflation.

Interest payments grew from 6% of government spending in 2020 to 13% in 2024, making it the fastest growing component of government spending—and already surpassing the outlay on Defense and Medicare. This state of affairs is clearly unsustainable. The tax base capital is so dependent on for bailouts and subsidies is collapsing.

The Trump administration is naturally desperate to bring borrowing rates down and is making moves to pack the Fed with its own people in order to get its wish sooner rather than later. When the Fed lowers its interest rates, market rates usually follow to some extent even if the Fed’s rate falls lower absolutely. In recent years, however, market rates have spiked in response to a lower Fed rate in anticipation of higher government debt and inflation, making debt more expensive to repay while relatively disincentivizing borrowing, investment, and dealmaking (i.e. mergers & acquisitions).

With inflation still stuck at 3%, above the 2% target aimed at maintaining business stability, the Fed is today much more reluctant to intervene than in the past. US inflation hit a forty-year high of 9% in 2022, impacting not only assets as in the aftermath of 2009 but also, this time, consumer prices. The average basket of goods is now 25% higher than in 2020. Coffee is still up 21% in the past year and ground beef 15%. Overall monthly inflation is only ‘low’ because of falling house and oil prices, and when the latter falls too low to retain profitability, oil production will be cut in order to hike prices, something that would certainly burst the stock market bubble.

For now the Fed is planning to drop its rates—possibly to zero, as it did, for the first time ever, in 2009 and then 2020—and print money to buy debt at an even greater rate than it did in 2008 and 2020, when the money supply grew by a shocking 40% in less than two years. At the start of December the Fed stopped tightening its balance sheet (as it has done since 2022 in its fight against inflation) and started reversing course. Sacrificing the housing market, instead of reinvesting in maturing mortgage-backed securities, proceeds will go solely into purchasing government debt in a desperate bid to bring down the cost of government borrowing.

The Fed’s coming intervention will again devalue wages and savings, amounting to another, likely greater round of relative inflation in terms of lost purchasing power combined with or followed by overall deflation as investment plummets. That could come after a period of inflation and therefore even higher interest rates if and when the price of oil shoots up.

To sufficiently reincentivize investment, to whatever degree that remains possible, the capitalist state will have no choice but to limit bailouts to a smaller proportion of the private sector (compared to in 2008 and 2020, when it did allow a portion to fail in order to centralise wealth, re-enabling accumulation for the winners); and making even greater cuts to spending on welfare and public services. At some point, though, it will likely have to bite off more than it can chew, as the costs of its warmongering, on labor and rivals, will become completely unaffordable or completely destructive.

Death Knell

Liberals and social democrats will blame Donald Trump’s anti-migrant policies for exacerbating labor shortages along with his tariffs—taxes on US importers and consumers which are impacting demand and draining reserves; but which are designed in part to tackle a government deficit that has been mounting over several decades.

Trump and his policies are symptomatic of deeper structural rot. The reality is that capitalism unavoidably generates the conditions of its own downfall. In summary, making profit of course requires growth (of commodity production) which, via innovation that speeds up production, tends to result in the devaluation of commodities and, in the long run (since devaluation initially lowers the cost of investment), less profit per commodity. Capital is therefore increasingly dependent on making the state its biggest customer and bleeding the public dry.

As the general rate of profit falls, investment opportunities dry up, resulting in ‘overaccumulated’ gluts of surplus money capital that cannot be profitably reinvested. Karl Marx’s contention that this immanent barrier to innovation and productivity growth tends to grow “more formidable” is illustrated in many ways: by the record high prices of cryptocurrency, gold, and speculative stocks, for example; and the amount of dead cash amassing in US money market funds, hitting $7.5 trillion in 2025, up by a phenomenal 33% in just three years.

Via bankruptcies and mergers and acquisitions—the recent deals between the likes of Nvidia and Open AI represent a gigantic proto-merger—the ownership of capital and wealth necessarily concentrates in order to offset falling profitability; excluding an increasingly large proportion of the population from the capitalist class, which is therefore pushed back into a corner of its own making from which it lashes out increasingly aggressively, stimulating an intensifying class struggle through which the working class must eventually prevail.

As capitalists continue to automate their operations in the effort to lower outlay and re-widen profit margins, the contradiction at the heart of the system is increasingly aggravated. No wonder AI is unprofitable—data is produced and rearranged at increasingly breath-taking speed. Not to mention that capital accumulation requires capital-intensive (expensively extractive) solutions (in order to produce exploitable labor time); while the relatively falling supply of skilled labor, due to education costs capital cannot afford, is making the skilled labor needed to produce and train AI increasingly pricey (producing a new and emerging proto ruling class of wealthy workers). Unlike humans, robots and computers cannot be exploited through wage labor for profit or buy commodities capitalists need to sell. The fully automated system of production capital itself reaches for is making capitalism historically obsolete and (global) socialism necessary.

Why socialism? Empirical economic data again makes the case clear: that concentration of capital through bankruptcies and mergers is demonstrated by the fact that, despite 50 years of aggressive privatization, the number of private banks and corporations in the US has roughly halved since the turn of the century, while the overall proportion of startups has also declined. That trend goes back much further, but the merger trend has tended to accelerate since 1990. A ‘final merger’ in the not-too-distant future evidently beckons—to be enacted by a socialist state, since a capitalist state cannot by definition socialize the whole private economy—necessitating the transition to an economy owned entirely by the public, since no exchange of ownership is necessary in a total monopoly.

This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the number of currencies in the world is trending towards zero, with the US dollar and UK pound both having lost nearly 100% of their purchasing power over the past century, indicating the approaching necessity of a moneyless economy.

Private enterprise itself, furthermore, is increasingly centrally planned, with the elimination of ‘internal markets’ (competition between departments) and the introduction of centralized databases in order to erase duplication and other inefficiencies, enabling decentralization as all data is accessible to all parts of a network. Central planning the economy as a whole is the next phase of this evolution.

A long, painful, unavoidable struggle awaits—but so too, at last, does working class and human liberation.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.