Reading Ted Reese’s response to my criticisms of his recent Cosmonaut article, I found that much of my warnings about the limits of pure empirical analysis went unheeded. When Reese says that he focuses on “collating a very comprehensive array of empirical economic data…to see if these already established theories do in fact play out in practice, in real-world capitalism” I believe he summarizes the issue very well, in collating vast amounts of empirical data, Reese fits these facts into theories so as to construct narratives he’s familiar with. What Reese does not do, however, is create an understanding of a theory by operationalizing its concepts via empirical facts. What exactly is the difference between these two approaches? The first approach, of narrativizing theories with facts, cannot actually challenge one’s pre-existing notions, whereas operationalizing a theory, such as by applying its mathematical categories or logically thinking through its implications, can radically change one’s understanding of an underlying theory as well as reality itself. Here, I will show what I mean by this, going in order of importance.

Profit Rates

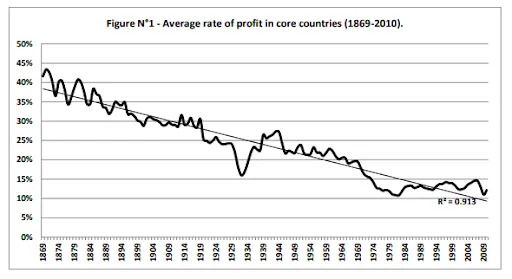

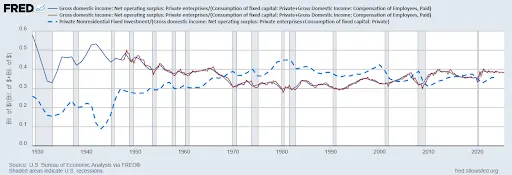

In his original piece, Reese made several comments which attempted to explain high financial speculation via falling profit rates, and I had pointed out that under neoliberalism profit rates had not fallen, but rather stagnated secularly. Initially, Reese seems to misunderstand my comment about stagnation to be about real GDP growth, which, while lower than the pre-neoliberal period (and this is where debates about secular stagnation come from), are still positive, however eventually we do get to the meat of the debate about profit rates. He cites studies such as the one by Esteban Ezequiel Maito to say that there is a tendency for profit rates to fall progressively to zero, but Maito’s study itself, while it of course saw a negative slope in its linear regression for profit rate data going back to 1869, also identified the same plateau (or stagnation) in profit rates beginning in neoliberalism, and not just in US data but in core countries more generally.[1] Since Maito’s data ended in 2009, this could at the time be taken as a temporary aberration, but here we are almost 20 years later and the situation is about the same. Similar stagnation can be found in the data from Basu et al for the US.[2] I’ve included Maito’s chart so that readers can judge for themselves in these matters.

Reese does suggest that more narrow measures of profitability around the non-financial sector may yet show the sort of decline which feeds into the mechanisms he’s been talking about regarding heightened financial speculation, specifically citing Michael Robert’s works. As he says: “In the non-financial example the rate clearly trends down from 17.2% in 1997 to 11.5% in 2020.” That might seem ironclad enough, but if one steps back a moment, something might seem strange about that ending date. 2020. Wasn’t there something else happening that year?

Indeed, in nearly every dataset of profitability, there was a major decline during COVID, which was both severe and brief. Profitability quickly recovered, and in the graph, Reese cites it is exceptionally clear that the large decline during COVID was not an indication of a broader secular decline, as according to that measure, profitability in 2019 was ~15%, not far off the 1997 high point.[3] In short, there is absolutely no case for saying that profitability, whether general or nonfinancial, has experienced a significant decline during neoliberalism, and certainly no reason to assert that the rise in financial speculation, including crypto and gold the past few years, was the result of falling profit rates.

Reese doesn’t explicitly admit this point, but does accept that the measures required to support the rate of profit at its current levels and prevent its fall may be behind much of neoliberalism’s peculiar symptoms.

Investment Rates

There is one section from Reese’s letter which I think summarizes his approach to testing theories and which I’ll quote in full:

Marx though obviously needed empiricism for the basis of forming a theoretical framework. He then investigated empirical observation by using the method of successive approximation: abstract schemas (mathematical patterns) that simplify the process of capital accumulation are made less and less abstract by reintroducing elements of capitalism originally left out, testing the results from the abstraction against more realistic versions of the social system. Just as with the maximum abstraction, the more complex schemas deliver the same theoretical conclusion: capital overaccumulates and the rate of profit falls – to an increasing degree – confirming the empirical reality that had motivated Marx to begin his investigation. Nevertheless, complex schemas are still naturally quite abstract.

With the advantage of another 130-odd years of data, we can test Marx’s theoretical conclusions against empirical reality and vice-versa – and conclude that empirical reality rather compellingly backs him up. That is the work that needs to be done most pressingly, for Marx (and Henryk Grossman, his best defender) have already provided the scientific theoretical framework.

The primary problem I have with this understanding of theory is that it begins from the conclusions and works backward. What does it mean for capital to overaccumulate and the profit rate fall? Is it some fundamental law of the universe? Surely not, as from the very beginning, Marx insists on the historical contingency of capitalism. If it is a fundamental law of capitalism, then there must be specific reasons and causes for why that is the case. Indeed, Marx spends pages and pages of his magnum opus thinking through this logic of just why capitalism leads to overaccumulation and falling profit rates. It is therefore not simply the observation of overaccumulation and falling profit rates that can vindicate Marx, but the observation of the whole chain of causality that Marx outlines as the specific causes of over-accumulation and falling profit rates. If profit rates are secularly falling purely because of a falling rate of exploitation, this would entail a mark against Marx's notion of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, as he had assumed it would be the result of rising productivity and capital intensity. If profit rates have ceased to fall, the reason why also matters deeply here; after all, many different economists have postulated tendencies for falling profit rates for different reasons. Marx assumed that falling profit rates were the result of the internal logic of capital. If profit rates fall because the economy has deviated in some way from the broader logic of capital, then this is not so much a problem for Marx’s theory, but a problem for the economy.

My contention is that we have seen a departure from the logic of capital in neoliberalism, and this is the reason for the stable, not falling, profit rates, in neoliberalism. This is connected to the issue of investment rates as I brought it up in my earlier letter, however, due to several erroneous interpretations of these theoretical concepts and empirical facts, I'm not sure Reese has grasped the significance of this.

Reese suggests that financialization has occurred because profit rates have fallen due to classically Marxist reasons: that the ratio of labor to capital has fallen, even though he acknowledges that investment rates have fallen. Unfortunately, these two things are incompatible. Let us recall some basic facts about economics: the capital stock and its depreciation are determined by previous investment, and investment is always some share of surplus. The Kalecki profit equations are very helpful here, as in their simplified form, they show that Gross Profit = Capitalist Consumption + Gross Investment (or alternatively Net Profit = Capitalist Consumption + Net Investment). Assuming a stable rate of exploitation, therefore, the only way for the ratio of capital to labor to fall is for investment to take up a larger share of surplus. For example, if we have a depreciation rate of 100%, then investment will always equal constant capital, so the relationship between investment and labor will be the same as capital to labor. Since Marx assumed rising capital intensity and organic capital composition from competition-driven productivity gains would drive down the rate of profit, Marx's tendency for the rate of profit to fall is exactly identical to a tendency of the investment rate to rise. Indeed, if we examine the rate of profit data and investment rate data together, we see that the huge decline in profit rates coincided with a precipitous rise in investment rates, and that the rise of neoliberalism entailed a reversal in the rise of investment rates, which correlated with the minor secular recovery in the rate of profit.

When Reese says “...it is silly to point to one trend line on one chart and say that the theory in this case does not apply. That one chart or trend line may look OK in the period concerned; but GDP growth, labour productivity growth and R&D growth have all fallen decisively across the neoliberal period; and the quality of human life – the loneliness epidemic, the explosion of chronic illnesses, and so on – has evidently continually declined,” he is speaking out in favor of motivated reasoning, rather than scientific analysis. I point to this strange historical anomaly of neoliberalism’s investment rates and profit rates not to falsify Marx’s theories; indeed, I don’t believe it does that, except for a few notions Marx had about the capitalist class being capital personified. I do it in order to fully understand Marx’s theories and their implications. Here, it is crucial to separate the secular trend from the cyclical change. In terms of secular economic development, Marx precisely predicted that capitalism would lead to world-historic growth in terms of the mass of commodities (what we call GDP today), as well as labor productivity and scientific innovation, even though he was adamant that capitalism would continue to face severe cyclical crises. The secular transformation of capitalism under neoliberalism, particularly in its anglophone epicenter, caused it to have declining investment rates, rising profit rates, lower capital intensity growth, lower GDP growth, and lower labor productivity growth. These things are not in contradiction at all! This is exactly what Marx, and indeed all the classical political economists, would have expected to go together. Adam Smith perhaps put it best when he said “…the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity, and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich, and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries that are going fastest to ruin.”[5]

This ruination could eventually create a political crisis for neoliberal capitalism by making the conditions of the mass of people that much worse, but it does not appear at all that this tendency for falling investment rates actually represents a direct problem for the capitalist class, rather than a boon. Investment rates are not, as Reese suggests, going to zero, at least in terms of gross investment. Net investment rates, perhaps, can be said to be converging towards zero, which is just to say that the capital stock is stabilizing in relative terms, neither growing nor shrinking.[6] There is a certain myth (not repeated by Reese here, but is common) that capitalism needs growth for profit to exist, or to reproduce itself on an extended scale. This is not true. As was mentioned earlier, profit is equal to investment plus capitalist consumption, which can exist whether there is growth or not and also means that the less capitalists invest the more they can consume, hence why neoliberal stagnation is primarily a political, not economic, challenge to the capitalist class; when there is no rising tide to raise all boats, those already afloat aren’t so concerned unless they face the wrath of those left behind. It should also be noted that a high investment rate can present a problem for the capitalist class independent of profitability, for the simple reason that capitalists need to consume a certain amount to reproduce themselves as a class, as the more investment that’s required to reproduce a system of production, the less room for actual capitalists.

State Capitalism

Regarding the issue of what exactly state capitalism is, and whether or not it is our future, I do not mean to imply that state capitalism is just “the government doing things” or otherwise having an important role in the economy. I mean something more specific: that the state takes on the role of the idealized capitalist as laid out by Marx. This means that the state is pushing forward higher investment, raising capital intensity and labor productivity, revolutionizing the means of production, and maximizing the exploitation of labor within cultural and historical limits. What makes China’s state capitalism “more authentic” than previous incarnations, is that when the previous incarnation of state capitalism pushed investment rates to such levels that the reproduction of the capitalist class began to be placed at risk it led to the breakdown of the state capitalist system and the emergence of neoliberalism, China’s powerful Communist Party and its control of state enterprises and the financial system means that the state can direct investment and production without the involvement of the capitalist class if necessary, something the western state capitalism could not do.

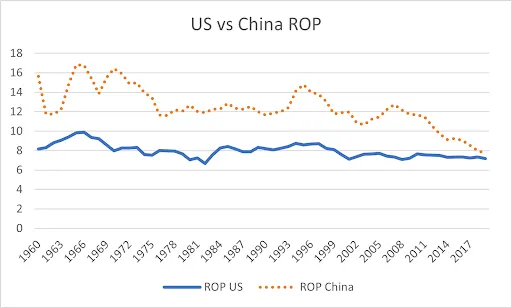

China’s investment rate is more than double that of the US, and this has led to a rapid decline in profit rates there. Indeed, it is not right to say that “...China’s capital is younger and therefore has not yet suffered from overaccumulation to the same extent,” if we compare the profit rates of the US and China, we can see that China had already converged to US levels by 2019, and has likely fallen further since given all the complaints about low profitability and “involution” in the press.

Reese suggests that the current level of Chinese state ownership, and presumably investment rates, will not be tolerated by the Chinese bourgeoisie. Where this power of the Chinese bourgeoisie is expected to come from, I am not sure, considering even the mildest criticisms of the party by large capitalists are liable to receive harsh censure and suppression. He suggests that when profit rates fall to an unviable level, Chinese state support will be withdrawn from an industry, citing the withdrawal from real estate. But it’s important to note that the Chinese state did not step away from supporting real estate because of low profit rates, as China has supported many low or even negative profit rate industries in raw materials for decades as a means of developing the productive forces of the whole economy. Rather, China stepped away from real estate because it had turned from a means of developing productive forces and increasing urbanization into a money pit of resources, where rapid depreciation of real estate projects was used as a means to secure ever more state support and thereby generate huge amounts of waste. In other words, the name of the game has always been developing the productive forces, rather than maintaining a reasonable level of profitability.

This structural role of the Chinese state is easy to differentiate from that of the US or UK, where all policy measures are taken to maximize capitalist consumption at the expense of all else, particularly investment. When I say that the UK’s crisis, which began with the great financial crisis and never ended was “avoidable” I mean that it was perfectly possible for the UK to have had a normal level of investment, given so many of its peers around the world were able to, even other countries with impeccable capitalist credentials. The US and UK are unique due to their role in capitalist imperialism; their level of de-industrialization was almost certainly so severe due to this structural role, which already in the years prior to World War 1 Lenin was calling out in the UK[8]: imperial surplus extraction cannot help but atrophy the domestic industrial base. The importance of US and UK financial sectors and other forms of rent seeking in the global economy mean they are the primary benefactors of such imperial surplus extraction. It’s in this way that the US and UK collapse in investment rates was avoidable, even from the perspective of its domestic bourgeoisie. Had the US and UK renounced and participated in the global economy primarily by selling actual commodities, their domestic bourgeoisie would have persisted, albeit looking a little leaner, and with the eventual risk of future falling profit rates leading to another crisis of capitalist reproduction. These discomforts and risks are things that the bourgeoisie of continental Europe, East Asia, and South America have simply lived with, after all.

Reese suggests that my emphasis on these divergent goals of the American vs Chinese ruling class is evidence of idealism. How can it be that what matters is simply that the Chinese “care” about developing the productive forces, and the Americans do not? Aside from the very material impacts of global surplus extraction, I do not believe it is idealist to note how particular states vary in the measures of reproducing their domestic relations of production. The reproduction of the relations of production is done via labor and its coordination, after all. When faced with the problem of the reproduction of the capitalist class during the profitability crisis of the 70s, there was no pre-determined “right” answer provided by history for the bourgeoisie; the course needed to be discovered by experimentation and adaptation. The Marxist perspective here cannot be that it was all inevitable as an extension of the logic of capital, it is rather that any and all options taken are restrained by fundamental economic laws with their own tradeoffs, none of which can escape the inexorable logic of capital that forces capitalism’s economic development to lead to its own destruction, which I consider to be as irontight a scientific truth as Darwinian evolution or the second law of thermodynamics. Of course, this logic only operates on a structural, rather than empirical level - perhaps empirical history could have escaped the death of capitalism by a global cartel of the bourgeoisie restraining investment and economic development, and therefore the logic of capital, the rise of a truly universal mediocrity, essentially what neoliberalism attempted to do. Capitalism could escape its destiny, but only at the expense of its dynamism and economic growth. But given that modern China exists, with its high investment rates and drive to develop the productive forces at all costs, this position is no longer tenable.

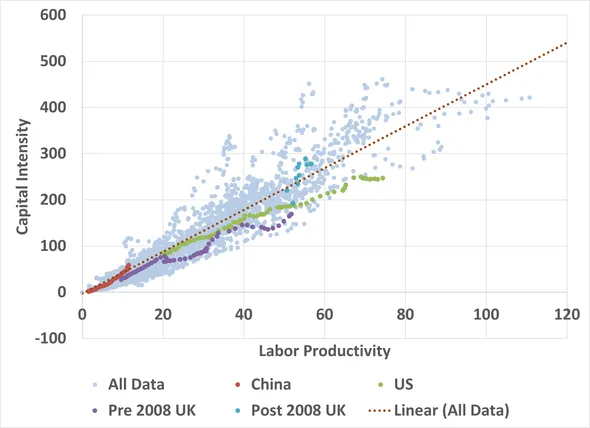

I don’t believe Reese misunderstands, on a fundamental level, Marx’s theory. However, it does seem that by failing to use this theory to examine facts and understand their significance, he has created a disorienting and confused method for applying it. For example, he says that UK capitalists were forced to innovate after the 2008 crisis to raise labor productivity and export over-accumulated capital overseas, except, as my graphic he was responding to showed, labor productivity did not rise by any significant amount during this period, but stagnated. This story Reese tells is the typical one Marxists might tell about an economic crisis of overaccumulation, and indeed this more or less describes what happened in the US after 2008, but as a matter of empirical fact, it did not happen in the UK. Instead, the UK’s labor productivity stopped growing as further investment raised capital intensity, pushing it back towards the global mean in terms of its relationship between capital intensity and labor productivity.

Similar issues apply to his less explicitly Marxist analysis as well, such as with debt and banking. Reese continues to insist on the importance of absolute quantity here, despite the fact that any liability would be as harmless as a hamster if the assets to repay it were readily available. The reason debt presents an issue to the US economy is not its quantity, but the fact that the US is structurally reliant on foreigners to plug the holes in both its capital and trade accounts, something that makes it, and the UK, unique among major debt-issuing sovereigns. Regarding bank financing and loans, Reese seems to want to have his cake and eat it too with the meaning of the relationship of loans to treasury and cash reserves, either this is a direct measure of how easy it is to profitably invest money capital, or it is a measure of financial excess. Indeed, if we are focused on the cyclical nature, we must first see the financial excess aspect, most crises after all are not the result of pure financial overaccumulation, but physical overaccumulation, whether that was internet infrastructure in the dot com boom, housing in the 2008 crisis (overaccumulation here being from the perspective of capital), or earlier crises involving railroads and international trade. This physical overaccumulation would just as well be seen in rising ratios of loans to treasuries and cash, but this would not necessarily mean money finding profitable uses.

Parting Remarks

When I think of genuinely scientific Marxist theoretical practice, I frequently return to the scientific aspirations of Marx, Engels, and Lenin and how they operationalized those aspirations. All three were well-versed in the political economy theories of their day, and spent significant effort researching empirical facts and statistics to understand where the truth and lie could be found in those theories so as to further develop their own models of things. There was no artificial separation between theory, as a fully realized system, and empirical research on the other, which merely verified this pre-established system, as the systemization of knowledge occurs as a part of a dialectic, even in the classical sense of the term, with broader empirical research. The purpose of making a theory rigorous is so that different empirical results can actually mean different things within the broader system; without this operationalization, the theory becomes a stale dogma. To permanently separate theory from empirical research is one of the greatest errors of our modern era of Marxism, whether by abandoning empirical research as many Marxologists and value form theorists are want to do, or by abandoning Marx’s theory in favor of regurgitating empirical facts with Marxist language, as many other Western academics do. Reese’s approach is puzzling because he has assembled both Marx’s theory, and a set of empirical facts for his readers, but has done little to actually put them together in any meaningful sense. Hence, we are left with a long list of contradictions, some of which are contradictory even within the very same paragraph. To amend this would be a simple thing, only to take the time to treat empirical research in the same manner as Marx did.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Maito, E., The Historical Transience of Capital: The Downward Trend in The Rate of Profit Since XIX Century, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2014. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/55894/1/MPRA_paper_55894.pdf

↩ -

Basu et al., “World Profit Rates, 1960-2019”, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2022

↩ -

Roberts, M., “The US rate of profit in 2020”, The Next Recession, December 5, 2021 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/12/05/the-us-rate-of-profit-in-2020/

↩ -

“Gross Domestic Income: Net Operating Surplus: Private Enterprises/(Consumption of Fixed Capital: Private+Gross Domestic Income: Compensation of Employees, Paid) | FRED | St. Louis Fed.” 2017. Stlouisfed.org. 2017. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=1568389#.

↩ -

Smith, Adam. 1776. “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.” Https://Www.gutenberg.org/Files/3300/3300-h/3300-H.htm. 1776. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3300/pg3300-images.html.

↩ -

“Consumption of Fixed Capital: Private/Private Nonresidential Fixed Investment | FRED | St. Louis Fed.” 2017. Stlouisfed.org. 2017. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=975439.

↩ -

Basu et al., “World Profit Rates, 1960-2019”, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2022; https://dbasu.shinyapps.io/World-Profitability/

↩ -

“Further, imperialism is an immense accumulation of money capital in a few countries, amounting, as we have seen, to 100,000-150,000 million francs in securities. Hence the extraordinary growth of a class, or rather, of a stratum of rentiers, i.e., people who live by “clipping coupons,” who take no part in any enterprise whatever, whose profession is idleness. The export of capital, one of the most essential economic bases of imperialism, still more completely isolates the rentiers from production and sets the seal of parasitism on the whole country that lives by exploiting the labour of several overseas countries and colonies…An increasing proportion of land in England is being taken out of cultivation and used for sport, for the diversion of the rich. As far as Scotland—the most aristocratic place for hunting and other sports—is concerned, it is said that “it lives on its past and on Mr. Carnegie” (the American multimillionaire). On horse racing and fox hunting alone England annually spends £14,000,000 (nearly 130 million rubles). The number of rentiers in England is about one million. The percentage of the productively employed population to the total population is declining” V.I. Lenin. 2019. “Lenin: 1916/Imp-Hsc: VIII. PARASITISM and DECAY of CAPITALISM.” Marxists.org. 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/191;6/imp-hsc/ch08.htm.

↩ -

Villarreal, N., “The Chinese Encounter”, October 15, 2025. https://nicolasdvillarreal.substack.com/p/the-chinese-encounter

↩