Can capitalist management thought provide solutions to the problems of the socialist movement? Jean Allen urges doubt and skepticism in this critical review of Morgan Witzel’s A History Of Management Thought.

Authors note 2020

This is the paper that made me a socialist. It’s odd to say that, seven years later, and especially odd to say that as someone who has for a long time advocated against the idea of finding communism at the end of a term paper. But it was precisely this term paper, written in the dark hours in my shabby Arlington apartment, which pulls from a dozen books paged through on the bus and which ends with a weak call for workplace democracy, that broke the years of largely self-imposed conditioning and put me on the path I travel now. Realizing that our economy was run via undemocratic methods that did not work even by their own standards was something I could not turn back from.

So it is even odder to say that now, seven years, this piece has become relevant again. Recently a comrade of mine, Amelia Davenport, wrote an article in this journal that speaks to a project we are both involved in: the development, within the socialist left, of a science of organization. I agree with them that the organized left has gone for far too long with proto-scientific methods, accepting tautological nonsense or ideological statements in place of analysis of organizational conditions. Realizing this allows us to start along the path of materially analyzing some of the largest issues facing the left today. It is possible to build an organization which deals with the tradeoffs of democractic decision making and effectiveness, of autonomy and coherence, of responsibility to the part and responsibility to the whole, of inclusivity and clarity, in a way that is amenable to the majority of our comrades

But, in an odd way, my comrade wrote an article which this piece is a precise disputation of, despite its having been written seven years ago. While I agree that the development of an organizational science for the left is of absolute importance now that we have a left worthy of an organizational science, what my comrade goes too far in saying is that we can look to bourgeois management science and take it, in its entirety, and use it to our own ends. That is, to my tastes, thoroughly inadequate as a response. While there are mistakes in this paper (regarding the historicity of F.W. Taylor’s examples), I hope that it shows that management science performs just as much, if not more, of a role as an ideological justification for the inequity of our society and of the lack of agency the working class has in our society. There is, certainly, a kernel of an argument in management that we can use, but when we look at the study of management in bourgeois societies it is not ever truly clear what aspects of it describe a real situation and the right answer, and what exists purely as magical thinking, the final analysis put out by a dying era and a dying economic system.

I am not making an aesthetic argument here, that to use the language or thoughts of management thinking will somehow inherently infect us with Evil. Management thinking is by and large an organic ideology, and it has become so to the degree that it does not work even on the terms it sets for itself. While the failure of the social sciences and particularly business sciences to analyze the world did not produce Trump or Brexit or Bolsonaro, their failure is yet another of the symptoms coming from the decline of a period of technocratic liberalism and the growing desire for a strongman, a decider who is not bothered by the desires of the masses or any desire to relate to them, who can make our discipline work through sheer force of will. But this failure was not a fall from grace, the groundwork was flawed from the very beginning and it is for precisely this reason we cannot take management science on its own terms and use it for ours. It is not only not useful for our ends; it has failed on its own terms.

In the course of editing this work for republication to Cosmonaut I have mostly edited for style and to remove a graduate student’s penchant for unnecessary phrase-mongering. In doing so I have tried to keep its argument consistent with the article I wrote in 2013, with a final conclusion to discuss Davenport’s article and this piece, and analyze where we could find a middle ground between the two.

Authors note 2013

This paper began as a critique of Morgan Witzel’s A History Of Management Thought, a book that was assigned for a graduate course on Organizational & Management Theory. The work, which claims to be a summary of management thought from the beginning of civilization to the modern-day, had a large number of apparent flaws and ‘holes’ in its historical structure, but during my critique, I swiftly found that the issue was not the text itself, it was the flawed and ideological history that Management has built up around itself. As this realization dawned on me this paper moved from an attempt to ‘plug the holes’ of Witzel’s work (by presenting a discussion on the power structures of early capitalism which he glosses over) into a critique of modern management thought in general. Throughout this paper I attempted, to what degree I could, to present these ideas and my critique, sans jargon and in a self-explanatory way. I hope you enjoy.

Introduction

“How would you arrive at the factor of safety in a man?” Wilson asked

“By a process analogous to that by which we arrive at the same factor in a machine,” he replied.

“Who is to determine this for a man?” asked A.J. Cole, a union representative.

“Specialists,” replied Stimson.1

When a political proposition is made, its political nature is seen, critiqued, its power structures discussed. But if that proposition survives, if it lasts a century or for centuries, it is no longer a proposition. It becomes a social system, a system we are brought up in, a system we are taught within, a system we have a hard time thinking outside of. This is especially true of management thinking.

A hundred years after the Congressional hearing on Frederick W. Taylor’s methods, and after decades of depoliticization, management has come to be seen as a science, a fact of life. In the meanwhile, management academics try desperately to fix the disorganizing effects of management thinking. 2 What both the layman and the academic miss is that management thought is political and serves to hide and justify the power relationships which occur within the workplace. Within this essay, I will discuss the political dimension of management thought through a critique of Morgan Witzel’s A History of Management Thought.

Morgan Witzel’s A History of Management Thought is a task of amazing scope–an attempt to provide a survey of all management thought from the very beginning of civilization, showing that “since the birth of civilization, people have been writing and thinking about problems in management and how to solve them”.3 Despite Witzel’s goal there are significant holes in his narrative–several times he says with surprise that this or that major civilization “did not produce much in the way of notable work on business…[or] administration”.4 Such a finding is without a doubt ‘strange, even perverse’, but such major holes suggest a mistake, not so much in archival work as in historical perspective.5

History is more than looking back

R.G. Collingwood’s The Idea of History warns against thinking that the past is merely a backward extension of the present and thinking of writing history as a merely archival endeavor. Cut-and-paste history, as he calls it, is a school of thinking which attempts to understand the peoples and practices of the past without understanding the thinking of the past. He sees it as a critical misunderstanding of history–a method that turns the study of history into a series of technical problems:

“a mere spectacle, something consisting of facts observed and recorded by the historian. This is highly problematic because it reduced individual thoughts into a continuous mass, indeed the individual level is seen as an irrational element; through positivism “nothing is intelligible except the general”.6

Instead, he argues that thinking historically requires putting any event or reading within the context of the time and attempting to put oneself in the shoes of those one writes about.7 This requires understanding the way a different culture or time functions, and appreciating the way that the context of the modern-day presses itself on the study of history.

How does this relate to Witzel? Witzel writes very much in the context of his time, the modern era when business has largely taken over thinking about organizations and even military or governmental organizations use the language of business. The modern-day is a world where rapid technological changes necessitate constant thinking and rethinking of organizational principles. It is a world where management and organizations are explicitly talked about, in books and articles that come out by the hundreds each year.

Our context is very different from even the immediate past. Explicit thinking about business did not start until the 18th century, and explicit thinking about management started in the late 19th century. Much of the thinking about management and business before this was ’embedded’ within society: people thought about management or organizations via analogies to other things which were more familiar to them. Without accepting the embedded nature of management thinking–an acceptance which would recast management thought as an ideology rather than as a discipline–accessing the past’s implicit thinking about management would be difficult if not impossible. This explains the major gaps in Witzel’s work before Taylor.

It also leads to a far more interesting question than why one university professor chose to write a history text in a certain way: what happened to change management thinking into an explicit discipline? People were able to manage massive organizations without a large corps of texts on management, and even as late as the 20th century there were many people who insisted that management could not be taught or explained to any satisfactory level. What led to the change?

This question–what events led to the emergence of management thought as a discipline rather than as a series of societal beliefs, is the key question of this essay. To answer it, I will examine Witzel’s text, as it is above all else a perfect example of a traditional history of management, while also constructing an alternate explanation for the creation of management science. This essay will be organized into three sections corresponding to three eras of management thinking. Through the first section, which will follow the time when management was an implicit mode of thinking, I will discuss three civilizations which Witzel says ‘did not have much to say’ about management (Rome, Ancien Regime France, and Ming China) as well as others to attempt to explain the hole in his narrative. With the knowledge gained there, the second section–following the 19th century and the creation of an explicit field of management–will explain the reasons for management’s shift into the public light. And in the third section (going over the 20th and 21st centuries), I will return to discussing the holes in Witzel’s narrative and how the origins of management still affect it today.

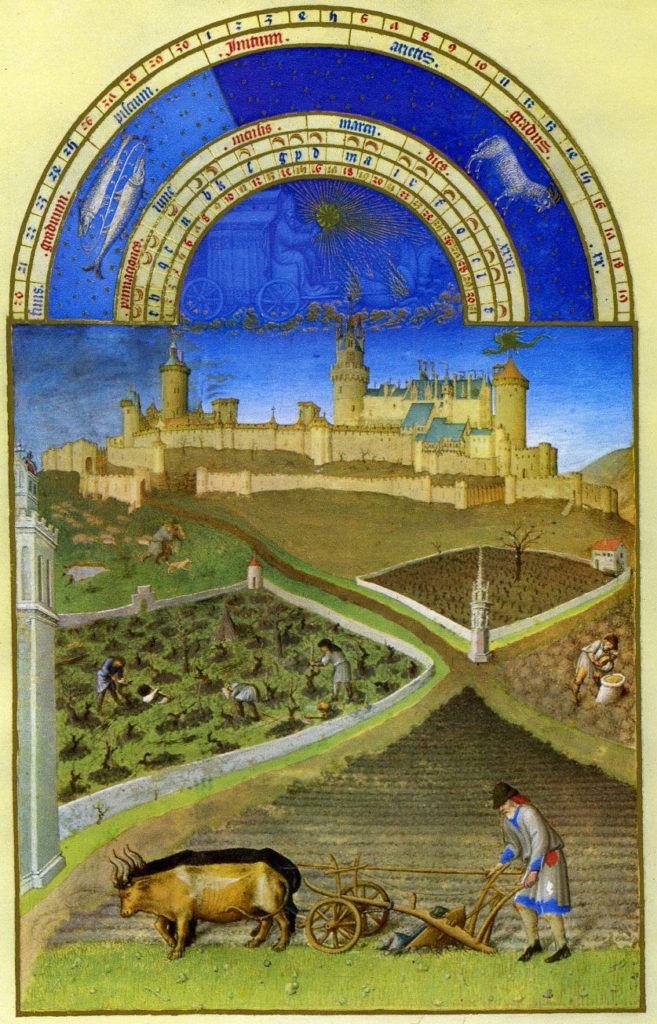

Family Manors: Management before 1789

Witzel’s choice to begin his discussion of management thinking at the very beginnings of human civilization is both a highly innovative choice while also opening space for problematic history. Many traditional histories of management have started with Taylor’s work or immediately earlier, and in doing so are able to talk about management science in the context of society relatively similar to ours rather than the massively different societies we saw centuries if not millennia ago.8

Witzel begins with the origin myths of several societies, describing how the very different origin myths of Greece, India, and China attribute the rise of civilization to some powerful leader and from this evidence states that these myths show that even ancient society expected things like competence from their rulers. From this Witzel begins to discuss the genre of ‘instructional texts’ given to rulers as the earliest origins of thinking about management.9

But the rulers of ancient Egypt or China were substantially different from the modern-day manager. Witzel merely notes the similarities between the Maxims of Ptahhotep and modern self-help books without noting the massive differences in the societies they came out of.10 The Pharos of Egypt, Kings of Babylon and the Emperors of China had far more responsibilities than any one manager: they were managing whole societies and were responsible for the justice system, the military, the state’s finances and the weather. Similarly, the justifications of this management were substantially different, depending on a connection between the monarch and the divine being of the society. For all the self-centered middle managers who read the Art of War in order to get a leg up in petty office squabbles, these texts were not written for them. Not only were the monarchs of the classical era managing all of society, but they also represented all of society.

But this is only the beginning. Witzel argues later on that the Pre-Socratic Greeks and the Romans “did not produce much in the way of notable works on business…[or] public administration”.11 This is where an oversight becomes a glaring error. There is no way that the Romans could have run an empire spanning Europe, an Empire that was impeccably organized and won through the efforts of the most efficient and ruthless army of its time without a massive amount of thinking about management.12 But Witzel gives us a clue to his mistake. By linking business and public administration, he tells us that he is looking not for ‘management thought’ but for ‘business management thought’, the business of the Classical era very different from modern-day business.

Regardless of culture and society, business was almost always seen as a dirty job during the pre-Victorian era. The only legitimate form of wealth gained, regardless of whether one is discussing Republican Rome, Ancien Regime France, or Ming China, was wealth gained from land ownership. Indeed, merchants often gave up better profits in order to gain entry into the aristocratic class, a tendency which could be seen in societies as disparate as 18th century Paris.13 and 14th century China.14 Such a tendency tells us that wealth, the accumulation of wealth, and the very idea of business was not seen as particularly important.

R.G. Collingwood noted a similar trend in his analysis of the ‘history of history’. He found that history had always been used analogically, and was viewed as a peripheral way of looking at the central philosophical problem of the time.15 This central philosophical problem, be it mathematics in Greece, theology in Medieval times, or the discoveries of the hard sciences in the post-Enlightened age, completely changed the way that history was studied. The goals of Medieval history were the discovery of the nature of god16, and the discovery of man’s universal nature imparted by god17, notions which were taken for granted and rarely exposed to criticism. Thus the kinds of historical knowledge gained by the Medieval Christians were often not what we would call historical knowledge, but theological knowledge presenting itself as history, even if the Medieval scholar still called his field ‘history’. As such we can say that history was an explicit field that was predicated on implicit societal views.

Paul Chevigny, in his book on police violence, describes another implicit phenomenon. He argues that since policing is seen as a “low” occupation unworthy of academic study or thought, the way that most people think about everyday police work occurs analogically: we think about policing as a subset of the way we think about ‘justice’ or ‘human rights’, not as a topic in and of itself.18 Thus policing is an implicit field of study which is thought about analogically through the explicit notions we have about society. This distinction will become important as we discuss management’s emergence as an explicit field. Until then, I will leave it that management was an implicit field before the Industrial Revolution, a notion which Witzel discusses (“most earlier authors did not set out to write works on management”)19 but does not seem to appreciate.

While pre-Industrial society practiced ‘management’ daily, they thought about it analogically: since business was seen as a “low” skill, management thinking was almost entirely an implicit field of thought which came via analogies to more familiar and more important institutions: the family, politics, religion, or ethics. Wealth was something to be attained in order to gain stature and political power, and once that stature and power were gained, the new aristocrat immediately took on the anti-business concept of their peers. Timothy Brook notes this trend throughout the Ming Dynasty: noting a plethora of nouveau riche aristocrats decrying the kind of practices that got them where they were and consistently attempting to hide the shameful, commercial, origins of their own wealth.20

Even though business (and indeed the very idea of working to make money) 21 was seen as a ‘low study’, Witzel argues quite successfully that businesses expanded into worldwide ventures during the Medieval period, which led to thinking about specific necessities of management such as accounting.22 The Enlightenment’s project of questioning established norms also led to a large amount of thinking about economics and eventually business.23

This leads to a question: if firms (if they could be called that) were doing business on a global scale as far back as the 12th century and the individual branches of management (finance, accounting, administration) were in place around the same time24, why did it take until the late 19th century before a complete concept of management came forth? Specifically, what changed to make businesses seem like a respectable element of analysis, and what changed that necessitated the creation of management thought?

Beyond the anti-business biases of pre-industrial society, aristocratic societies across the world developed an organic ideology that naturalized the idea of the inherent superiority of the aristocracy which came from their blood and breeding. This impeded the development of management thinking in two key ways. The first being that since ability was to some degree inborn, there was little to no need for teaching or even thinking about management. The second followed from the first: if the aristocracy was inherently capable, then the mercantile and working classes were therefore subhuman or otherwise incapable of agency, an ideology which meant that there was no need to develop a set of ideas based around specifically managing other individuals. These two intellectual products of the feudal economy combined with an allegorical view towards businesses made the development of management thinking unnecessary. It took not one but three revolutions to shake this framework.

That aristocrats had inborn abilities was commonsensical to the people of the pre-Industrial era. Many of the patrician families of Rome claimed to be descended from Gods25, and both Ming China and Ancien Regime France had a concept of gentlemanliness (in French, gentilhomme and in Chinese junzi), an inborn concept which placed one irrevocably above his peers. Gentillesse was a characteristic that could only be provided through the blood: “the King might create a noble, but not even he could make a gentleman…[gentillesse could only be created] by deeds, heroic deeds, and by time. Two generations usually sufficed”.26 The gentilhomme was a larger than life character, capable of more destructiveness and more greatness than any mortal could possibly grasp. The junzi was a remarkably similar character, a person beneath only the sage (a saint-like figure) in societal placement. The junzi was literally translated to ‘lord’s son’, which keeps with the inherited nature of nobility. The junzi, moreover, was defined by his ability to see what the everyman could not: his virtue and knowledge of the classics led to transcendent accomplishments inconceivable to the ‘small-minded’.27

Besides the gentleman’s construction as a sort of anti-business person (the French gentilhomme was a martial and artistic figure while the junzi was at heart an academic living isolated from the world), the conception of in-born gentlemanliness challenged management from another front.28 Witzel notes that as late as the 20th-century British business schools would not teach management, believing management to be an “aristocratic x-factor”, something which could not be taught.29 This gets to the heart of the problem: why think about management if the ability to lead was simply in the blood? Why not think about, instead, the blood? Pre-industrial societies shared widespread horrors at the possibility of miscegenation, and the societal punishments involved in a gentilhomme family marrying a non-noble one were so strong that no such combination has been found.30 Love between the Indian castes and Chinese classes was viewed with similar anxiety.31 This anxiety (and the complicated categories of nobility and peasanthood constructed over the centuries in nearly all societies) indicate that people saw inborn abilities as being so much more powerful than thinking about management that “certain physical characteristics exemplifying nobility were intentionally sought out and bred”.32

This belief in the inborn abilities of the nobleman had another side to it: a disbelief in the ability of the poor to think or act for themselves. The Fronde, a civil war in 17th century France, began because the crown considered the nobility as responsible for the revolts of their peasants: “in seventeenth-century society, peasants and artisans were considered to be something like leashed animals, and when they revolted, the king, the bishops, and the nobility frequently blamed the nobles…for not keeping the peasantry in hand”.33 Because the peasants were considered to be ‘childlike’ and obviously followed their superior masters, revolts along the Seine valley (caused by food shortages and egregious taxes) were considered to be aristocratic plots rather than a reaction by individual actors.

A similar example of individuality being viewed as either an aberration or as the purposeful malice of the master can be seen in the American south. During the 19th century, a pseudo-science was built around understanding the origins of slave revolts and runaways. The idea of Drapetomania, that is, the irrational want to run away from one’s masters, was prescribed as slaves reacting to masters “attempting to raise him to a level with himself”. That the position of the African slave is given as “the Deity’s will”34 is a common trend that occurs in readings from all over the world in the preindustrial era.

The belief in a hierarchy ordained by a divine being (or by the laws of science) permeated nearly all pre-Industrial cultures, manifesting in different ways in different societies. In India, it manifested as literal castes,35 in China in the ‘Nine Ranks’36, and in Europe as the Gentilesse/Noblesse/bourgeoisie/peasant distinction. This hierarchy created an interlocking set of beliefs which destroyed the need for management thinking. These beliefs in the supernatural and inborn powers of the nobility, the lower classes’ lack of agency, and the unimportance of business all combined into a feudal ideology that devalued the idea of social mobility, devalued the individual (excepting the aristocratic individual), and also devalued the unheroic task of running a business. Combined, they formed an organic ideology that allowed very little room outside of it. If nobility is inborn and nobility is only gained through ‘heroic’ acts, why care about running a business? If the peasants had little to no agency, why think about managing them? If social mobility is de facto impossible except through the state and the nobility, why invest one’s time in a business when a title is clearly so much more important?

This set of questions explains Wiztel’s surprise in finding little to no development in management thinking in Chinese, French, or Roman cultures: they thought about management analogically, through metaphors to leadership (which they considered inborn) and the family. The workplace, the prime focus of management, was seen as merely another, inferior, aspect within the broader society. Furthermore, management rests on an a priori assumption of a relatively equal relationship between the boss and the worker. The worker could be fired, the worker could work poorly, the worker could leave but in management, the worker is assumed to have agency, an agency which did not exist either conceptually or in the reality of the latifundia workplace.

The examples that Witzel finds of proto-management in the pre-Enlightenment era occurred in exceptional cases where upheaval destroyed the idea of inborn ability (Machiavelli’s Il Principe was written to the victor in an assumed coup, an event which occurred often in Italian city-states), or in the case of something considered far more important which management then adopted as its own (warfare). Simply put, the class society of feudalism could not conceive of management thinking, either as a science/means of analysis or as a justifying force in society, because it already had a justification for the hierarchy that existed within it. Often this aristocratic ideology was incapable of ‘working’ either by any objective measure or even on its own terms, but without an alternative system and a different material base, this form of magical thinking hung vestigially over society, justifying all sorts of harm and oppression despite being debunked and demystified. For centuries humanity hung between a feudal society that created all manners of useless suffering and a new method of organization that could not be spoken of let alone analyzed. This is a state I think we can relate to, and feudal notions hung onto relevance until it was felled, not by one Revolution but three.

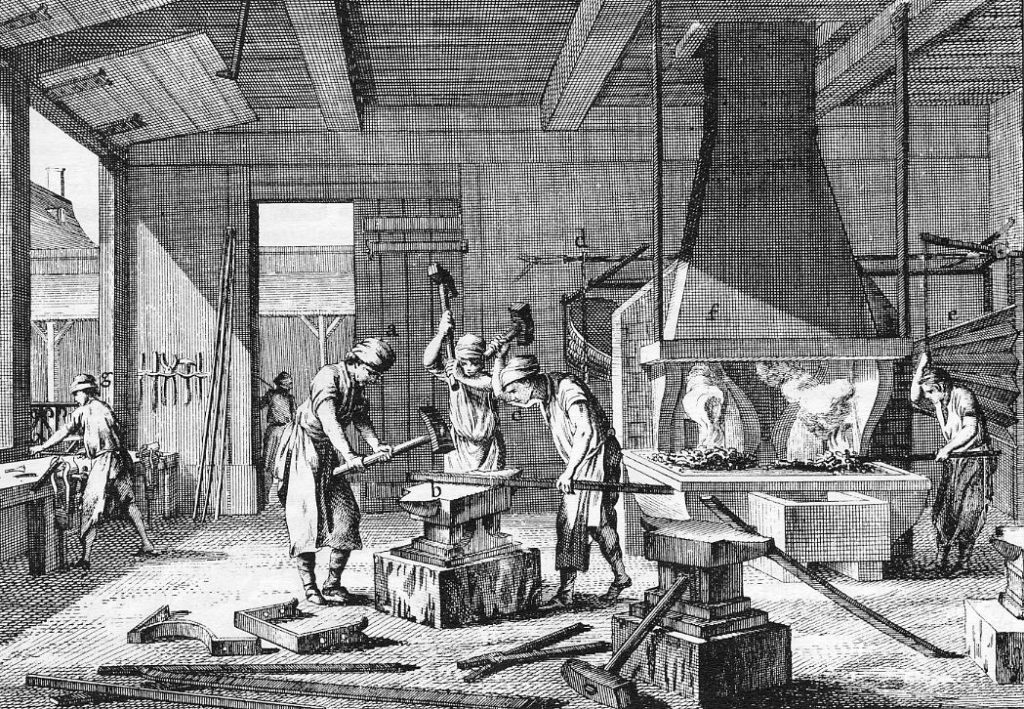

The Republic In the Workshop: Management as Reaction

The general notion of history is as a march to the present. It is the mistake of every society to think that the zeitgeist of the present day came about as the result of a series of won compromises and that we are living in “the best of all possible worlds”. The typical view of American history takes this viewpoint: the Founding Fathers are not seen as revolutionaries in their time, promoting a radically different system than what had came before, but as conservative figures in our time, promoting the current system that we have. Each step in American history: the revolution, the extension of suffrage, the abolition of slavery, the new deal, the civil rights movement, etc, is seen as a step towards the present that could only have gone this way when in reality each event had an infinite number of possibilities. From the perspective of the contemporaries of Washington, Jackson, or Lincoln, it was not so obvious where the events of their lifetime would lead.

I say this because Witzel’s history of management is written in a similar fashion: management is depicted as a natural outgrowth of the world.37 which would have emerged in roughly the same form regardless of the thinking of Taylor or of the events of the 19th century. Management was simply an answer to the organizational problem of factory life, which was merely waiting to be found by whoever picked it up. I will argue in this section that once management is put in its political context it becomes far less innocuous.

While the feudal ideology I described in the last section was collapsing in Europe over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, it was only the events of the late 18th century (the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution) that finally broke the back of the aristocratic notion of inequality among the classes. It was the notion of equality, conceptualized and argued through many world civilizations but then given form by the bourgeois-republican governments of France, the United States, and Britain, that attacked both the notion of inborn ability by allowing any man to stand for office and the idea that the poor had no agency by allowing the poor to vote.

The idea is that these movements occurred naturally, that the abolition of slavery or the extension of the franchise was a natural outgrowth of the birth of capitalist democracy. Hierarchical structures like slavery, the caste system, and noble privileges were economically insufficient, and thus their dissolution was inevitable. Such a construction ignores that these orders were as ideologically rooted, the deconstruction of these orders requiring revolutionary action in their time. And even if we accept that slavery’s dissolution was inevitable, the way in which an event occurs and what exactly replaces it is just as important as the event of dissolution itself.

Similarly, even if we take the eventual development of a field of scientifically minded management as a given, the kind of management thought that developed was just as important as the fact that a form of management thought emerged. Multiple strands of management thought grew at once in the late 19th century, and despite much of Taylor’s work being based on forgeries, Scientific management dominated all other forms of management in the early 20th century. This is because scientific management was about more than merely solving problems: it was an ideological response to the threat of socialist and democratic movements who sought to bring the logic of republicanism into the workplace.

Manifestations of this tension appeared throughout the Western world during the early 19th century. The rise of socialist and anarchist organizations, not to mention the development of unionism, all placed pressure on typical workplace relations. Their reasoning had its roots in the juxtaposition of liberty in the voting booth combined with autocracy in the working floor: “the consequence [of capitalistic relations] now is, that while the government is republican, society in its general features, is as regal as it is in England”.38 The pamphlets of the Workingmen’s Party (Workies) also featured a discussion of the similarities between chattel and wage slavery:

“For he, in all countries is a slave, who must work more for another than that other must work for him…whether the sword of victory hew down the liberty of the captive…or whether the sword of want extort our consent, as it were, to a voluntary slavery, through a denial to us of the materials of nature…”39

Similar events occurred in France. After the 1830 July Revolution, French workers waited “for the introduction of the republic in the workshop”. The “applied republic”, that is, a democracy which was replicated within the workplace, was a common call from the July Monarchy through to the Third Republic. It was in France during the election of 1848 that the first divergence emerged between “a social republicanism, seeking direct application of republican principles in the economic sphere, and a republicanism that sought to restrict these principles to the political sphere”, with the purely political republicans winning.40

Despite the victories of capitalistic republicanism in the early 19th century, social democratic parties and movements continued to gain strength, with the German Social-Democratic party becoming the largest single party in the country.41 The French created a word, sinistrisme, to describe the situation of the 3rd Republic wherein the leftist parties of one generation would become the right of the next as increasingly socialistic parties appeared and took their place. The reason for the continued decay of the 19th-century rightist parties was their tendency to use traditionalistic (that is, reliant on the feudal ideology I explained in the last section) justifications for the injustices of society, and the reason that Taylorism was so successful was that it finally presented a new and comprehensive argument against republicanism in the workplace: by creating “one best way” for all workers the manager is able to make everyone better off.

The argument that if the workers were only to sublimate their desire for agency gained via social movements and their relationships with each other into a desire for agency gained via the piece-rate system and their contract with their manager then everyone would be better off was able to convince social justice advocates such as Louis Brandeis, and leading many technocrats including Witzel to see anti-capitalist critiques as merely desires for better management.42 This shows the degree to which Tayloristic methods have survived within management: the wicked problem of workers asking for representation is changed into the technical problem of workers needing better managers. By viewing the problem of worker’s dissent and indeed the problem of autocratically managing another human being as a technical problem, Witzel is able to argue that the answer was “to make management more efficient and to restore harmony with the workers”.43 In effect, Witzel is able to erase the ideological aspect of both scientific management and the workers’ movements and to present a movement which disempowered workers as the restoration of harmony.

Taylor’s process was to watch a laborer at work, design a better way to do that job, and then to require each and every worker to work at that pace. This disempowered workers in several ways:

-

- It was yet another moment in an ongoing process of deskilling, turning autonomous workers into merely imperfect pseudo-automated machines without knowledge of their subject which could be used without the manager’s assent. 44

- It applied the division of labor hierarchically–all thinking to be done about the nature of the job and the task was to be done by management and the consultant (a division shown by consistent comparison of the manager to the ‘brain’ in organic metaphors of management and organizations.45

- By arguing that most firms were inefficient and that the “scientific” methods applied by experts were superior to rule of thumb methods, Taylor was implicitly denying the worker’s own experience and knowledge and alienated the worker from their ability to better the work-processes they engaged with on their own terms.

Taylorism and scientific management took its focus, the workplace, and transformed it conceptually from a part of society subject to society’s rules to an area of perpetual exemption, no longer shackled to the magical thinking of the where utter autocracy was allowed to rule under the rubric of efficiency. This allowed one to be simultaneously a democrat in general while being an autocrat in the workplace. The contradiction of capitalist republicanism, while not resolved, was now obfuscated.

The Dismal Science and the Pathologies of Management

Economics has often been called the dismal science because the needs of ‘science’ requires a perfect seeming model which rests on many assumptions. This is just as true of management: after expressing all of its arguments through algebraic notation and even after constructing highly complicated models meant to create computer simulations, it still deals entirely with the most difficult of variables: unabstracted, individual, human beings, and under a highly mutable criterion: efficiency.46

The first issue of management is that any problem involving the interaction of human beings in the social sphere is a wicked problem, which was defined by C West Churchman as “a class of social system problems which are illformulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing”.47 The number of these problems which appear in the management of people represents an intractable issue to expressing micro-level workplaces formulaically, let alone utilizing those formulas towards any useful end. Wicked problems are highly contextual which interacts badly with scientific management’s claim of ‘one best way’s and universalism.

The second problem of any scientific management is with the idea of efficiency. Deborah Stone, in her work Policy Paradox, notes that efficiency is an almost completely subjective measure, that is what is efficient for one actor may be inefficient for another.48 Management has simultaneously constructed efficiency as the manager’s efficiency, erasing the perspectives of the infinite other actors whose lives could be ‘more efficient’ at the sacrifice of the manager.

It is fully possible to create a scientific discipline under these conditions: psychology, philosophy, and history all deal with these problems. However, management has not responded to the problems of unclear criterion and mutable variables by embracing critical methods. Instead, management has leaned harder on scientistic methods, methods that ape the aesthetics of the hard sciences without regard to the differences between studying the interactions of electrons and studying the interactions of people.49 Efficiency has been discussed as if it were an objective physically extant variable rather than a construction that was then reconstructed in a specific way. Over and over again the vacuous baubles of the org chart and process chart have been embraced, leading to expensive reorganizations which do nothing but redraw the chart. Indeed management’s continued embrace of scientistic discussion has led to an overfocus on the organization (which, like efficiency, is treated like an objective physically extant object rather than a construction) leading to a management thought which does not have much to say about work and people–supposedly the two subjects of the discipline.50 And despite all of this faux-scientism, management has become inundated by pseudo-academic gurus who pump out books that tell people that they can take charge in the workplace in X easy steps by the hundreds.51

All of these trends emerge from management’s original sin: that it did not emerge as a way to create knowledge. Instead it emerged in response to two needs: first, the need to create a coherent justification for authoritarianism in the workplace, and second, the anxiety of managers who want easy answers to their immensely difficult problems. Like history during the middle ages, management has become an explicit field based on implicit views that management itself helped create (the necessity of an authoritarian figure in the workplace, the need for ‘objective’ analysis, the specific way that Taylor constructed efficiency). Because management stands on unquestioned concepts, the discipline has found itself riven with pathologies of its own making, finding itself breaking apart even within its own rules.

The pseudo-scientific methods of the gurus are an example of this. While they are decried by management scholars their methods are actually highly similar to Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management. During one of Taylor’s consultations, he asked 12 of the strongest men in a factory to simply ‘work harder’ and then guessed that under this level of work these men could haul 72 tons of steel (which he rounded to 75) instead of 42, and from this concluded that 75 tons of steel as the minimum amount of steel one could haul per day. This is not the seed of a scientific discipline.52

While scientific management has not succeeded in providing answers to the problems of the manager, it has succeeded in building a highly resilient ideology around itself, an ideology that has been based on the aping of scientific methods and the continued arguing of the necessity of an authoritarian figure in the workplace. The result has been the successful depoliticization of Taylorism and the continuation of the ‘gospel of efficiency’ to the degree that people now talk of efficiency as if it were an objective measure. However, the trends which have emerged from management’s original sin have started to become highly problematic, not only for those on the outside of the discipline but for the discipline’s practitioners.

Disciplinization and the ‘silo effect’ is one of the pathologies which has emerged from management’s attempts to don scientific garb. While the splitting up of management into different sub-disciplines has as much to do with the m-form organization (a way of organizing firms wherein each task would have its own department/division, an organizational method which had its roots in the divisional structure of armed forces53 as it does with the academy, the silo effect, which is the complete separation of the management sub-disciplines into their own self contained worlds academically and creating fiefdoms within organizations, is one of management’s major pathologies. This phenomena has two aspects: the academic aspect (the silo effect which occurs in the academy) and the practical aspect (the silo effect that occurs in the workplace). I will explain each in turn.

The academic aspect of the silo effect emerges straight from management’s origins. The belief in the need for experts and the simultaneous disbelief in the importance of the lived experience of the workers creates a need for a highly specialized expert class with knowledge which is independent of the workplace, that is a managerial class with a “view from the top” rather than a view from the workplace.54 And at the same time, scientific management and its successors have little to say about power relationships within the workplace. This dual absence – the absence of work and power from management – has exerted a centrifugal force on the management discipline, leading to disparate sub-disciplines.

A look at an example of good organizing, the Valve company, shows why such a sub-disciplinary trend is necessary from a control mindset. In the Valve company, there are no formal control structures, everyone is allowed to move around, and because of this, everyone, from the accountants to the lawyers to the managerial executives, is asked to gain a degree of knowledge in programming, which is the company’s specialty (Valve 2012 39-40).55 Without a rigid command structure originating from an invented concept, Valve requires everyone to have a common language and thus asks for T-shaped people (that is, generalists who also have a specific capability) because commonly held knowledge allows for easier collaboration.56 This syncretic, ‘liberal arts’ viewpoint of management is exactly the opposite of mainstream management teaching and thinking, because management is not concerned with work.

Instead, management takes as its focus the invented concept of the organization and how to best rule that invented concept. From this highly sterilized viewpoint, hierarchies become so necessary that they are rarely thought about. Authoritarianism in the workplace, which was so problematic in the 19th century, has been reconstructed as a battle between efficiency and equality, a battle which goes unexamined.57 Further syncretic knowledge is unnecessary because tasks are split into their component parts, allowing each part to be done by a specialist (a phenomenon which would not be unfamiliar to Taylor or Ford).58 This factory viewpoint leads to necessary overspecialization by academics and management students because cooperation between the highly disparate parts is assumed.

And yet when management students come to the workplace they find that cooperation is rarely forthcoming. Because management has historically seen all of the things which grease the wheels of cooperation. such as talking and building social relationships within one’s job, as unnecessary and wasteful.59 Furthermore, when cooperation is modeled by management thinkers, it often looks little like what we would think of when we think of cooperation. Works like Bardach’s Developmental Dynamics: Interagency Collaboration as an Emergent Phenomenon places ‘acceptance of leadership’ as one of the key steps/goals of collaboration while simultaneously complaining of agencies which worry about “imperialistically minded agencies [which] might steal a march on them”.60

This fear of collaboration leading to annexation emerges from management’s lack of focus on the work and on management’s competitive mindset. Because ‘the work’ is seen as comparatively unimportant compared to the need for control, collaboration must be done for some other goal besides merely getting things done. And because competition is seen as more important than cooperation, management often transforms cooperation into a competitive activity. One example is the imperialistic theories which Bardach uses wherein each step is a step towards control. In such an environment there is little reason to cooperate, leading to the silo effect within the workplace.

But what is tragic about management is that despite the pathologies and its inability to provide technical solutions to wicked problems, its logic has become massively powerful within our body politic. The growing influence of management thinking over politics will be the focus of the next section.

Ever more dismal

While modern-day management has failed in many respects, its promise of technical solutions to wicked problems has made it hugely successful as an intellectual lens. We can see this because even while management academics try to find a new form of management, they wring their hands about the loss of control and the chaos brought by equality. Even Valve, a model of new management, asks ”So if every employee is autonomously making his or her own decisions, how is that not chaos?”.61

Management thinking, despite its flaws and pathologies, has moved out of the workplace to become a part of the contemporary zeitgeist. This has produced two strange juxtapositions. First, while the pre-Industrial world saw business only via analogies to more important institutions (the family, the church), in the modern-day business has become the sole operating lens through which other institutions are viewed. We see government, the arts, nonprofits and even families as analogous to businesses and thus reduce them to a specific kind of economic lens.

Second, due to this domination, management, which was once used to defend authoritarianism in the workplace, has now become a way to argue for authoritarianism in the body politic. In our modern system, we are such advocates for democratic systems that we are willing to go to war to (supposedly) establish it in other countries while being unwilling to establish democracy in any substantial way domestically. We believe that man is worthy enough to weigh in on matters of national security, the country’s economic system, and even how one’s schools should be run, yet we do not believe that man can be trusted to have a say in the events that go on in their workplace. The paradox of democratic capitalism which produced management has now been wholly obfuscated by it.

A perfect example of this is the discussion of the role of the president in our political system. A massive series of worried articles have come out in the last 4 years saying that the job of the president “is to somehow get this dunderheaded Congress, which is mind-bendingly awful, to do the stuff he wants them to do. It’s called leadership”. This scarcely rises to the level of a statement. Through the last 20 years we have seen increasing demands for authoritarianism in the name of efficiency, in the name of the government ‘getting things done’, which are scarcely ever connected to a statement about what things the government ought to do. These vague requests emerge from the powerful yet meaningless demands of management thought and the way that they have mapped onto our politics. Just as management is absolutely sure of the need for an authoritarian manager while having vague answers for what a manager should do in any situation, in politics we know we need an authoritarian president so he can do something instead of listen to parliamentarians bicker over what to do, we just do not have an idea of what exactly we need that authoritarian president to do.

Similarly, so many policy arguments in the public sphere have been reduced to great man-ist arguments. The “Green Lantern Theory of Geopolitics”, also known as the “Confidence Fairy Theory”–the idea that “the only thing limiting us [in foreign policy] is a lack of willpower” has been used by conservatives and liberals alike to attack non-managerial approaches to policy.62 Practically, the idea of ‘willpower’ and ‘confidence’ is so vacuous that the idea that it is used in foreign policy talks seriously is almost laughable. But the ‘willpower’ argument is used to argue for an authoritarian figure in public policy just as scientific management is used to argue for an authoritarian figure in the workplace. In fact, things have devolved. We are so entranced by the power of authoritarian figures that our arguments are reminiscent of the faux psychologists who diagnosed slaves with drapetomania. The confidence argument has been used practically to argue that merely treating foreign rulers with respect–for instance, bowing to a foreign king weakens the confidence other countries have in our power and our will to use that power.

Twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the supposed total victory of democracy over all the tyrants of the world, a new yearning for autocrats is being expressed everywhere, from the fringes of the left to mainstream neoconservatives to libertarianism. This autocratic argument is new: it is not the old feudalistic argument for a person who represents the father of the whole nation. It is instead expressed in the language of Taylor, and the desire to transform our messy and muddled political arguments into the idealized hierarchy envisioned by management. Phrases like “It is for the experts to present the situation in its complexity, and it is for the Master to simplify it to a point of decision” appear even from leftist sources.63 The idea that if only we were more courageous, willful, and authoritarian that we would be able to make the hard decisions easy, that within each wicked problem is a technical answer which we could find if only we had an authoritarian figure with enough willpower, steps from the faith we still have in the system of scientific management. We believe that, like fairies, the manager will only be able to provide us with easy answers if we believe in the system enough.

These emerging trends, which came out of scientific management to become far larger than the factory workplace it originated in, are hugely problematic: the belief in a society of simple and rational answers is so enmeshed that any of its failures are attributed to the failures of individuals. This belief is larger than management and the schisms within the management field: just as positivism is based on a very particular and superficial notion of the hard sciences64, our current management norms are based on a very superficial idea of modern management thinking.

The line of thinking which I have been discussing is not directly connected to ‘the work’65 but rather to an idealized view of the way that workplaces should work. This is because this line of thinking has always been about control rather than results, and due to this the changes that have occurred within management academia have had little effect on management as it is practiced. In Witzel’s last chapter he does bemoan the disconnect between management and management academia, saying that “management thinking is now the province of the academic”.66This is not, strictly speaking, true: management fads and gurus have in many ways a broader audience than management academia. This is even more problematic than the possibility Witzel (rightly) presents, that management may be obsoleting itself by closing itself to the non-academic world.67 Management academia has a far better ability to turn management into a truly intellectually rigorous field in which the assumptions of management are questioned with the goal of creating more knowledge rather than upholding an ideological framework based on control than the guru cottage industry is. While this is not to say that management academia has served a progressive role, the willingness of management academia to specialize itself into obscurity is highly worrisome.

This gap desperately needs to be breached if management is to become a more rigorous field. But that is not enough. Larger participation in management by different parts of society,including workers, needs to occur both at the practical and academic levels in order to get management focused back on work and interpersonal relations. The larger problematic attitudes of society towards management need to be deconstructed at every level. Simply attacking them in the academy will not be enough. To some degree, the task is obvious. Addleson’s concept of ‘ubuntu’ (that is, connectedness with one’s group) and a more inclusive and democratic view of management is necessary in the context of knowledge work. But while being simple, the task is immensely difficult. Even if we accept that management’s replacement is inevitable, that scientific management gets replaced is not what matters. It is how it is replaced and what replaces it. And I have no answers with regards to that.

Conclusion: The Collective Mind

Much of this essay feels very dated as I write this in the spring of 2020. The dismissive attitude towards any kind of systemization, the confidence in workplace democracy as the only solution needed to these problems, the lauding of Valve of all things, all come off as the writings of a sharp if naive and new leftist writing a college paper in a very conservative institution. In this segment, I will speak to two elements which I was naive about (workplace democracy and the paper’s focus on ideology), before speaking to the ways this article applies to our current situation.

The naive excitement about Valve’s managerial model aged the worst of my concluding statements. The belief that a non-hierarchical corporation was a potential solution to the problems of management thought was not a conclusion I leaped to on behalf of my college, it was, at the time, an earnestly held belief. This belief was misplaced. A company who’s manual might as well be titled ‘ways to create a tyranny of structurelessness’ naturally moved to more hierarchical and frankly abusive management styles as the decade wore on (if, indeed, the original model ever truly existed in the first place). Furthermore, the idea that workplace democracy would be able to maintain it’s democratic structures within a capitalist system is ludicrous. What we’ve often seen instead are groups that allow workers to enact the same workplace discipline on themselves that a manager normally gives, a discipline that does not just emerge from managing styles but from the needs of the market.

The argument I consistently made through the paper, that management should not be seen as an academic discipline but as a malfunctioning ideology, is one I would maintain. But there is a limitation to this. When I wrote this in 2013 I was in the midst of a painful rebellion from Obama era technocracy towards socialism, and this reaction still held marks of the idealism one can easily find in academia. In focusing on the cultural justifications each mode of production creates for itself I allowed myself to think that this justification was one of the main ‘pillars’ of a mode of production, and if it were only surpassed we would be able to surpass that mode. Such idealism is anathema to the way I think now.

Feudalism was not primarily a series of ideological constructs but an economic system, and the same is true of management thought’s relationship to capitalist production. But there is a relationship between the superstructure and base, one where both are continually changing. The theme of a justificatory ideology slowly occluding the analytical elements which gave it vitality, leading to encroaching and, over time, fatal pathologies is one I have returned to again and again, with good reason. Management science was not conceived as a way to systematize the experience of workers into a theory of their work, but was rather created with the a priori need to justify autocratic workplace relations, a need which has over time overtaken the discipline’s ability to give knowledge about the subject for which it was created. This remains true whether the statements Taylor made were apocryphal and this brings me to discuss the recent article by my comrade Amelia Davenport.

Comrade Davenport is correct that the rule-by-thumb methods that organizers have developed over the last generation are insufficient to the task of running contemporary political organizations. She is also correct that what must replace that is a rigorous scientific method able to speak across contexts. At this point we part ways. While I cannot speak to Prometheanism, Constructive Socialism or our current ability to surpass scientific socialism (which all sounds nice but goes against my lifelong disinterest in abstractions), I do not think that Taylorism is the means by which we can reach a synthesis of theory and practice. We can see this in the lack of concrete examples in Comrade Davenport’s article. Taylorism confronted the complex problems of managing humans and solved this problem by treating people the same way one would treat machines, allowing engineering principles to be applied to the human body. Even if this narrowly worked within industrial production, it has only proven applicable to later methods of production in the most roundabout and analogical of ways and is not applicable to the variety of activities a political organization finds itself.

There is another method that we can apply analogically to our situation, which I would argue is a better analogy: the method by which Clausewitz attempted to train officers. Clausewitz correctly stated that war is a simple affair, but that within war, the simplest things are the most complicated. From this, he separated the study of warfare into two forms, the first being the science of war, which consisted of the creation of fortifications, the organization of a barracks, the logistics of war. These are relatively easily taught and, regarding our situation, should be standardized and taught to members in as quick a manner as is feasible so as to keep technical skills from becoming a boundary to participation. The other half of the study of warfare, the art of warfare, was far more difficult as it consisted of one’s ability to make decisions with limited time, limited information, and a large amount of chance involved. This does not mean that it was impossible to become skilled in the art of warfare, but for a long time it was something which could be learned but which, it was suspected, could not be taught.

This did not mean that there were not universal truths in warfare which Clausewitz found in his studies: that defense was a stronger form than offense, albeit one which could not win a war on its own, that warfare has a tendency towards escalation, etc. But this did mean that teaching a capable officer was a different task than teaching a capable engineer. You cannot predict everything that will occur on a battlefield, and seeing things in a mechanistic way where all must do is choose the right course of action as given to you by theory is a sure way to create a disaster. What Clausewitz did, instead, was teach his officers to replicate the decisions of past generals in their heads, without bias towards whether they were ‘right or wrong’, and try to understand why these generals did what they did.

This is the method we must use to train not just ourselves or those destined for leadership, but our whole organizations. The ability to critically analyze not just our actions but the actions of other groups is how we create nuanced and level headed organizers. But this is not something that can be standardized or mechanistically taught; it requires training one’s judgment, which is inherently a personalized process. This does not mean that it cannot be done. It would require many of the same things that comrade Davenport lists, but it would also require:

-

- The inclusion of a process of operational analysis including both analysis of our material conditions and criticism & self-criticism as often as possible, within group contexts and in writing.

- The creation of clear lines of communication and information exchange, publishing what can be safely and feasibly publicized, including these operational analyses.

- A focus on making as many decisions as is feasible democratically and including as many members as is feasible into the process of making decisions.

- An acceptance that, on the one hand, these democratic decisions are binding, but similarly that the minority viewpoint in each vote is to be respected.

At this point, we need to ask, ‘what is the point of democracy?’. Often we counterpose a positively coded democracy with the autocracy that people experience constantly in their day to day lives. But given the absolute dearth of democratic institutions, if we consign ‘democracy’ to being just ‘good’, we are laying the foundations for democracy’s undermining in practice even if we affirm it in word. Throughout the left, democracy is seen as something ‘nice to do’ if inefficient, a vision of democracy which leads to it being lauded in word and cast aside in practice. In other organizations, formal democracy is seen as the most important decision-making tool, even if that formal democracy impedes on the ability of the organization to act or practically limits the ability of people to interact with the process. Almost everywhere in the left democracy is affirmed at the point of decision and then cast aside when people move to implementation. These can easily lead to a curmudgeonly opinion, which is only outwardly expressed within at the end of a political cycle: that democracy is simply a waste of time, that if it is such a good thing to sit in a meeting hall trading points or order or consensing until our faces turn blue just to decide on the time of an event, that it would be better if we dropped it in the name of efficiency.

I am a member of the Democratic Socialists of America. In left circles, the idea of democratic socialism is often hand-waved as being limited to a project of developing social-democracy in an Anglosphere that has not ever had that uninteresting experience. But through working in this organization for years, I have gained a far greater appreciation for the concept. When I am giving a speech, democratic socialism is about creating a world that is both social and democratic in a world which is utterly undemocratic and anti-social. But going further than that, it also speaks to the fact that as human beings living under capitalism we have not had the experience of working in an organization that is democratically operating towards social ends. The life of the average proletarian is one of being told what to do without being able to respond, towards ends which would likely never exist without a profit motive, without the ability to influence the situation around them let alone change what task they are working towards. Indeed, even at the other end, your average manager may have the ability to make decisions but is still unused to that decision being made collaboratively. We are not used to thinking about the organizations which we operate in, either because we have a one-way relationship with those organizations, or because at the top these organizations are reducible to a handful of people working on a handful of projects, and can be worked within in the same way as any group of competing cliques. So when we are forced to interact with an organization, where not just us but the people around us all have a say in our decisions, we can be instinctively territorial, we can instinctively form into cliques, we can instinctively think not of the wellbeing of us as a collective but just of ourselves and our projects.

It is the task of all of us within the movement to build a collective mind, produced but not reducible to individuals, trained by but not reducible to our experiences, and we only build it by continually working in a democratic way. This means more than voting or reading consensus on something at the point of decision and then dropping democracy afterward. We need to operate democratically throughout every step of the process, from conceptualization to decision-making to implementation. This is not done out of some bleeding heart sentiment that it would be nice to do. We learn from doing, and the more democratic our processes are, the broader they are, the more people are included in that learning. When we make decisions and implement them in a democratic way, the whole group, not just a handful of staffers, organizers, or cadre, learns how to be more capable. When we work democratically we all learn about ourselves, our projects, the organizations we work in, the society we live in. The more we work democratically the more capable we are at making new decisions collectively, the more nuanced those decisions become.

Furthermore, we cannot put this off; we cannot wait for some moment to give us permission to flip the democracy switch. We will never be able to competently make collective decisions until we are asked to, until we try to, until we fail to. By making and learning from these decisions, we are able to better our organization’s ability to make future decisions. By fighting and losing in an internal vote and moving together regardless, we learn that our individual opinions are only important insofar as we work towards them, and strive to be better. Each time we decide on an action together and implement it together in a broad and democratic way, we teach ourselves and our comrades that our decisions matter. The dispersal of technical skills is an important aspect of this but it is the easiest one of the problems that face us. Dispersing democratic skills is far more pressing.

This is a problem that Scientific Management is unable to solve: it was never meant to build democratic organizations. Its conception of organizations can only be a top-down decision-making apparatus where a handful of people are given the ability to decide on behalf of their inferiors what work will be done and how that work will be done. It is categorically incapable of treating every element of a process as being guided by human beings possessed of agency because it ascribes humanity solely to the manager. This does not mean it is unscientific, just as with drapetomania it was an attempt to scientifically process an utterly ideological defense of an authoritarian status quo. This is not some revision that was added later, some fall from grace which occurred after scientific management was co-opted by capital. Nor was it some ideologically neutral technology that the Soviet Union was able to use in a substantively different way than the capitalist world. All of the faults and the degeneration that has come later up to the wholesale acceptance of magical thinking regarding willpower stem from the original sin of management thinking: that it was conceived as a justification for class rule.

Scientific management’s inherent flaws do not mean that we cannot learn from it: nearly every theory has embedded presumptions and flaws. Nor does it mean that we cannot hope to create a scientific theory of organizations that work towards the ends of socialism. But we cannot merely declare such a theory, and any such declaration made out of cobbled together past theories will not stick, because such a theory needs to come wholly through us, through our collective decisions and the new perspectives on old questions that such experience gives us. Just as we can only reflect on our collective decisions by doing them, we can only theorize our experiences by reflecting on them. True systematization, the kind of synthesis of theory and practice comrade Davenport speaks to, is not something we can merely jump to. The movement as a whole needs to be developed, not towards Prometheanism or Constructive Socialism specifically but towards a better understanding of itself and the world around it. Perhaps this will move in the direction comrade Davenport points to, perhaps it will not. It is out of the hands of any one person.

As socialists, our ultimate aim should be for the creation of a more humane and democratic world. To steer us there are the human and hopefully democratic organizations we fight within. While we should strive to liberate our comrades from the prison of rule-by-thumb, we should embrace the humanity of the organizations we fight within. We should strive not just to simplify our methods in such a way that the human element of need be abstracted, but to embrace and empower our humanity.

- Kanigel, Robert. The one best way: Frederick Winslow Taylor and the enigma of efficiency. (New York: Viking, 1997), 460

- Addleson, Mark. Beyond Management: taking charge at work. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 1

- (Witzel, Morgen. A History Of Management Thought. (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2011), 2

- Ibid, 26

- Ibid, 25

- Ibid, 151

- Ibid, 172-173

- Ibid, 1

- Ibid, 9-10

- Ibid, 10-11

- Ibid, 26

- Holland, Tom, Rubicon (London: Abacus, 2004), 5

- Ranum, Orest A, Paris in the age of absolutism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), 197-199

- Brook, Timothy. The confusions of pleasure: commerce and culture in Ming China. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 278

- Collingwood, R. G., and T. M. Knox. The idea of history (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946), 4

- Ibid, 55

- Ibid

- Chevigny, Paul. Edge of the knife: police violence in the Americas (New York: New Press, 1995), 270

- Witzel, 2

- Brook, Timothy. The confusions of pleasure: commerce and culture in Ming China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 96

- Holland, 18

- Witzel, 32

- Ibid, 54

- Ibid, 32, 33, 40

- Holland, 21-22

- Ranum, 135-136

- Wilson, xviii

- Brooks, 2

- Witzel, 131

- Ranum, 135

- Fukuyama, Francis. The origins of political order: from prehuman times to the French Revolution (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), 167

- Ranum, 136

- Ranum, 200)

- Ibid

- Fukuyama, 164-167

- Ibid, 146

- Witzel, 81

- Gourevitch, Alex. “Wage-Slavery and Republican Liberty.” Jacobin. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 May 2013. <http://jacobinmag.com/2013/02/wage-slavery-and-republican-liberty/>

- Ibid

- “Revolutionary France and the social republic that never was.” openDemocracy. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 May 2013. <http://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/vincent-bourdeau/revolutionary-france-and-social-republic-that-never-was>.

- Anderson, Margaret Lavinia. Practicing democracy: elections and political culture in Imperial Germany (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000), 273

- Witzel, 80

- Ibid, 83

- Mueller, Gavin. “The Rise of the Machines.” Jacobin. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 May 2013. <http://jacobinmag.com/2013/04/the-rise-of-the-machines/

- Witzel, 190

- Bardach, Eugene. “Developmental Dynamics: Interagency Collaboration as an Emergent Phenomenon.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11.2 (2001): 149-164.

- Termeer, C.J.A.M. & Dewulf, Art & Biesbroek, Robbert. (2019). A critical assessment of the wicked problem concept: relevance and usefulness for policy science and practice. Policy and Society. 1-13.

- Stone, Deborah A.. Policy paradox: the art of political decision making. Rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 2002), 61

- Witzel, 184

- Addelson, 22

- Ibid, 232

- New Yorker, 2009.“Not So Fast” https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/10/12/not-so-fast

- Witzel, 163

- Addleson, 15

- Valve. Valve Handbook for new employees (Kirkland, WA, USA: Valve Company, 2012), 39-40

- Ibid, 42)

- Stone, 80

- Witzel, 191

- Addleson, 22

- Bardach, 153, 157

- Valve, 23

- Nyhan, Brendan. “The Green Lantern theory of the presidency.” Brendan Nyhan’s blog. N.p., 14 Dec. 2009. Web. 6 May 2013. <http://www.brendan-nyhan.com/blog/2009/12/the-green-lantern-theory-of-the-presidency.html>

- Zizek, Slavoj. “The simple courage of decision: a leftist tribute to Thatcher.” New Statesman. N.p., 17 Apr. 2013. Web. 6 May 2013. <http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/politics/2013/04/simple-courage-decision-leftist-tribute-thatcher>

- Collingwood,126

- Addleson, 22

- Witzel, 238

- Ibid