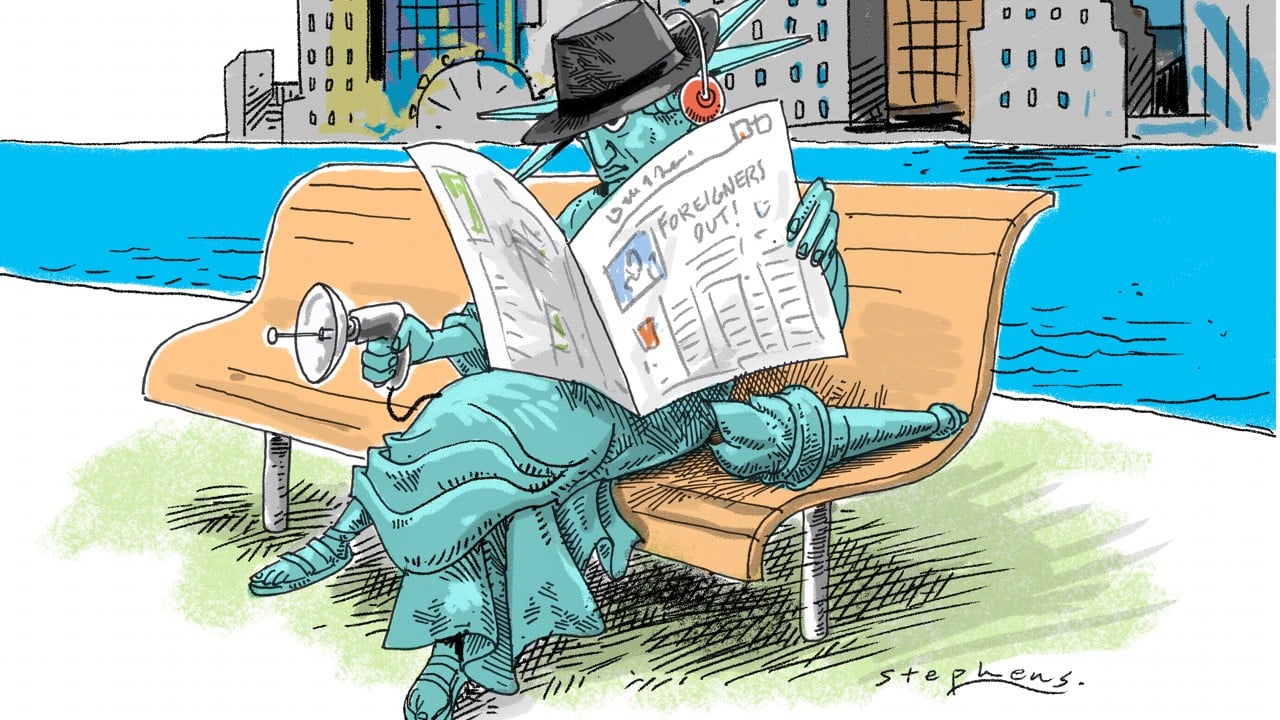

Steven De Castro raises the alarm about the weaponization of the Foreign Agents Registration Act against the left and provides advice on how to best work around the realities of an unjust and arbitrary law.

Since 2016, Democrats have been pushing the Justice Department to crack down on U.S. politicians serving as paid Russian agents. While this crackdown flows from the Democrats’ effort to pin Hillary Clinton’s election loss on Russian interference, it poses the problem that federal prosecutors may be casting wider nets that have the potential to threaten the work of DSA and other socialist activists.

As a result of this crackdown, the Justice Department has stepped up enforcement of a previously obscure statute from 1938 entitled the Foreign Agents Registration Act—FARA for short. Covington and Burling LLP reports on its website that “Prosecutors have brought more FARA prosecutions in the last several years than they had pursued in the preceding half century.”

FARA requires any person acting as an agent of a foreign power to register with the Justice Department and report all their political activities every six months. Failing to register carries a prison sentence of five years. This new interest in FARA enforcement led to the 2018 conviction of Paul Manafort, who volunteered as Donald Trump’s campaign manager while secretly serving as an agent of a Ukrainian political party tied to Russia, in exchange for payments totaling 17 million U.S. dollars. In August of 2022, the Justice Department went after African People’s Socialist Party (APSP). APSP founder Omar Yeshitela, 81, and his wife and co-founder Ona Zene Yeshitela, woke up in their home to the sound of flashbang grenades as militarized FBI units raided seven homes and offices of the APSP across Florida and Missouri.

On April 18 of this year, the Biden Justice Department unsealed an indictment accusing Yeshitela and others of FARA violations. Prosecutors say that the activists traveled to Russia to meet agents of FSB (The Russian Federal Security Service, successor to the KGB), and, over several months, received speakers and cash to make statements in support of Russia’s war goals in Ukraine.

Although most anti-imperialist organizations do not have Russian connections like those alleged against APSP, the case reveals the potential danger of selective enforcement against activists, either under Joe Biden or under a future administration.

It is only a matter of time before right-wing movements and other economic interests attempt to weaponize FARA to silence dissent against military spending, defense contracts, and proxy dictators by calling for investigations into activists who, for instance, oppose the embargo against Cuba or oppose military aid to Turkey or the Philippines. This case is a wake-up call for activists engaged in anti-imperialist struggle, human rights struggle, or international solidarity – essentially, any political activism which brings you into contact with people outside the United States.

These raids are also a wake- up call for me. In addition to being a lawyer, I am also a documentary filmmaker. In my film projects, I often engage with liberation movements abroad. Having worked with outlawed revolutionaries, I know that FARA changes the way I work. It could change the way you work, too.

Could FARA Expose DSA Members to Prosecution?

Any U.S. activist who regularly communicates with people outside the United States risks arrest, in the same sense that anyone driving a vehicle risks arrest, if the driver fails to learn the local traffic laws. In both cases, knowledge of the law can reduce your risk. DSA members working in anti-war, human rights, or other international issues are often in contact with unions, political parties, activists, and liberation movements outside the United States. When might they unknowingly cross a line? This raises the question of what constitutes a crime under the FARA.

FARA creates a federal crime with two elements: (1) a foreign principal, and (2) an unregistered foreign agent. U.S. activists can run afoul of FARA if their communications and course of conduct with a foreign principal meets the definition of foreign agent in the statute.

Just who is a “foreign principal”? FARA defines the term in a way that most people would not accept. During your travels, did you meet a farmer in Latin America displaced by a dam project, a college professor who told you about the human rights violations of U.S. funded paramilitaries, or a union leader who shook your hand at a rally in France? All are considered foreign principals under FARA. FARA defines a “foreign principal” as a foreign government or political party, any person outside the United States (except U.S. citizens who are domiciled within the United States), or any entity organized under the laws of a foreign country or having its principal place of business in a foreign country.1

FARA’s incredibly broad terminology obscures the fact that a U.S. citizen has the right to meet, converse, collaborate, and learn from people involved in liberation movements across the world, as protected by the First Amendment rights of free expression and freedom of association.

The second element of FARA with which we should be concerned is the definition of “foreign agent.”

The most controversial aspect of FARA is that Congress, in 1938, intentionally expanded the meaning of the word “agent” beyond how this word is commonly understood in U.S. law (it certainly goes beyond the popular conception of a foreign agent that the average person could have from a movie or novel).

In the statute, any American who acts at the request of a foreigner to engage in political activities could be considered a foreign agent. A foreign agent is not necessarily someone who is paid. The agent could easily be a volunteer or activist. Nor does the activist necessarily have to act at the direction or under the control of a foreign entity. To repeat, the registration requirement can be triggered if you engage in political activities at the request of the foreign entity. Pursuant to 22 U.S. Code § 611, Congress defines a foreign agent as any person who acts “at the order, request, or under the direction or control, of a foreign principal. . .” [Emphasis added]

FARA’s definition of foreign agent threatens to criminalize the most common activity that a U.S. activist is likely to engage in with a foreign entity. Victims of U.S. imperialism will always ask for help from Americans, to petition the U.S. government to stop military aggression, to stop U.S. support of a dictator, or to call for the release of a political prisoner.

Section 611 remains on the books, but court decisions and federal policies have attempted to limit the broad reach of the language. Judges and federal lawyers have lately recognized that Congress’ broadening of the term “agent” should be matched with a narrowing of the term “request.” According to this staff memo of the Congressional Research Service, The Second Circuit has recognized that the “exact parameters of a ‘request’ under the act are difficult to locate, falling somewhere between a command and a plea.” Holding that no single factor is determinative, the court determined that “[o]nce a foreign principal establishes a particular course of conduct to be followed, those who respond to its ‘request’ for complying action may properly be found to be agents under the Act.”2

How to Continue Our Solidarity Work Under FARA

To date, no DSA groups have been targeted by FARA. But in light of the increased rate of prosecutions, activists should create simple strategies to reduce their exposure. I have developed six guidelines designed to protect DSAers, not only regarding FARA but regarding infiltration by government and right-wing agents.

#1: Exercise discretion in all electronic communications.

Your emails and phone calls are supposed to be protected from warrantless search by the Fourth Amendment. Regardless, your communications with foreigners –whether through phone, chat, Zoom meeting, or email– can easily be monitored without a warrant under current law. No so-called secure app affords protection.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) “authorizes the targeting of foreigners even when this ‘targeting’ results in the ‘incidental’ collection of constitutionally protected Americans’ communications. As a result, the government can ‘acquire’ the contents of Americans’ e-mails, VOIP calls, chat sessions, and more when they communicate with people outside the US.”3

The strategy I describe involves using your communications to make clear the intentions of your actions. Any federal investigator conducting surveillance on me for FARA violations will be focusing not on others, but on what I say and do. Because I can control my actions and statements, I never feel the need to restrict what a foreign entity says to me over an email, because it is not my role to counsel a foreign entity.

#2: Always act based on your own viewpoint, and take care that your communications reflect that fact.

One should never, for example, say in a meeting, “The (foreign organization) thinks we should propose this resolution in Congress, so we should do what they want.” In any meeting, it should be clear that the organization’s decisions are the result of its own deliberative processes. In a deliberative atmosphere, a foreign entity’s viewpoint can be considered among others.

(T)he fact that a person is persuaded on a matter by a foreign principal and then advances that position is not, standing alone, sufficient to make him an agent. A foreign government’s explanation of its point of view, for example, may persuade a policymaker to adopt that position as his own; his (sic) subsequent actions in support of that position may be taken of his own accord, not as a function of any agency relationship. See, e.g., INAC, 668 F.2d at 161 n.6 (quoting Heymann Testimony at 701). At the same time, the fact that a person and a foreign principal may agree on a particular policy does not necessarily preclude an agency relationship, because lobbyists often agree with their clients’ views without losing their status as agents.4

For example, if a human rights organization in another country urges you to pressure the U.S. government to stop providing military assistance, your response by email should be noncommittal, but feel free to say that you will take this viewpoint back to your organization or consider this viewpoint as you formulate what action you intend to take. After consideration, you are free to agree with the foreign principal on the need to take the suggested action, which is constitutionally protected speech.

#3: Use this FARA Notice on written communications.

To inform the intended recipient that the communication complies with FARA, activists should provide the following notice:

FARA Notice. This communication is constitutionally protected speech originating from the author, expressing the author’s personal viewpoint, and it is not made at the order, request, or under the direction or control of any foreign government, political party, organization or person or any agent thereof. Cf. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) (22 U.S.C. § 611[c]).

The FARA notice should be used liberally, in the footer of every email. A FARA Notice should be on a flyer or email announcing a rally or discussion on an international topic. The inclusion of this FARA notice may seem insignificant now, but it may make a difference if the government reads the email, which could be many years from now.

Sometimes the small print matters. For example, a FARA Notice should be included in a meeting request to a congressional representative, because it will be helpful to assure the staff that the meeting request comes from a constituent and not from a foreign principal or an unregistered foreign agent. The FARA notice should technically accompany all political activity, which FARA defines as

any activity that the person engaging in (it) believes will, or that the person intends to, in any way influence any agency or official of the Government of the United States or any section of the public within the United States with reference to formulating, adopting, or changing the domestic or foreign policies of the United States or with reference to the political or public interests, policies, or relations of a government of a foreign country or a foreign political party.5

Although it is good practice to use the FARA notice, it is even more important to reflect on your communications and actions and ensure that the representation in the FARA notice is true.

#4: Avoid any kind of relationship that involves oversight or editorial supervision by a foreign principal.

Do not agree to submit one’s work for feedback to a foreign principal. Do not submit drafts of political documents for editorial approval. Avoid any relationship that involves a written agreement with a foreign principal (unless a lawyer drafts that agreement. In which case, that agreement will make clear that you are not a foreign agent.)

The Justice Department will be examining your entire pattern of conduct, so your communications as a whole should not suggest an agency relationship. Another way of putting it is that your communication with a foreign entity should never sound like you are talking to a boss or someone superior in rank.

#5: Consider whether it would be beneficial to register as a foreign agent.

In the course of your friendship with foreign persons, you could be asked to arrange meetings with U.S. politicians or to organize a conference within the United States to promote the views of a liberation movement or a political party. Although this request may make you nervous, nothing in FARA bars an American from assisting a foreign principal in their political activities, as long as you understand that registration may be required.

Wealthy foreign interests routinely employ paid lobbyists in Washington, D.C. Why shouldn’t working people have the same right to lobby for foreign liberation movements? If you have a project to promote a foreign movement that you believe in, consider filing the FARA registration and necessary reports, and then terminating your registration when the work is complete. Suppose you are unsure whether you need to register as an agent. In that case, it is common to request an advisory opinion from the Justice Department to determine whether or not registration is required. You can call the Justice Department FARA Unit at (202) 233-0777. They can even give you an appointment to come into the office and talk about it.

Although activists should generally avoid being classified as a foreign agent, they should not be afraid of registering as such, if a project is worthwhile.

#6: Do not accept money! Except. . .

Fundraising for a foreign entity likely demonstrates that the fundraiser is a foreign agent. In fact, accepting money on behalf of a foreign political government or organization in any context entails legal issues beyond the scope of this article. When in doubt, don’t.

However, keep in mind that humanitarian fundraising does not require FARA registration. FARA’s definition of a foreign agent specifically excludes “Persons engaged in the solicitation or collection of humanitarian funds to be used only for medical assistance, food, and clothing.”6 So if your organization wishes to help raise funds for victims of a flood or earthquake, humanitarian fundraising is specifically permitted.

These are not the only exceptions. An informational flyer of the Congressional Research Service provides that the following entities are not required to register under FARA:

- News or press services engaged in bona fide news or journalistic activities that are ∙ organized under the laws of any U.S. jurisdiction;

- at least 80% beneficially owned by U.S. citizens;

- run by officers and directors who are U.S. citizens;

and

- not owned, directed, supervised, controlled, subsidized, or financed by any foreign principal or agent.

- Foreign diplomats, consular officers, or other recognized officials and staff.

- Persons engaging in private and nonpolitical activities in furtherance of a foreign principal’s bona fide trade or commerce. By regulation, commercial activities of state-owned companies are considered “private” “so long as the activities do not directly promote the public or political interest of the foreign government.” However, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has concluded that tourism promotion is not private or nonpolitical activity because tourism fosters economic development, which is in every foreign government’s public and political interests.

- Persons engaged in the solicitation or collection of humanitarian funds to be used only for medical assistance, food, and clothing.

- Persons engaging only in activities in furtherance of bona fide religious, scholastic, academic, or scientific pursuits, or of the fine arts.

- Attorneys engaged in the legal representation of a foreign principal before a U.S. court or agency as part of an official proceeding or inquiry.

- Agents engaged as lobbyists for a foreign nongovernmental person, corporation, or organization if the agent has registered under the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995. Persons engaging in other activities not serving predominantly a foreign interest.

For us as DSA, the most important point is that, as the late Justice William J. Brennan warned, laws like FARA have the potential of creating a chilling effect on citizens’ First Amendment rights. In other words, the very existence of the law can deter people from exercising their political rights to advocate for human rights and international solidarity for the people of the world.

To fight that chilling effect, we must sound the alarm over this poorly written statute and avoid creating vulnerabilities for our opponents to exploit.

- See 22 U.S.C. § 611(b)

- (FARA): A Legal Overview (Updated March 9, 2023)

- Electronic Frontier Foundation, Government Explains Away Fourth Amendment Protection for Digital Communications, Andrew Crocker and Hanni Fakhoury May 13, 2014.

- The Scope of Agency Under FARA, Justice Department undated memo.

- 22 U.S.C. § 611(o)

- 22 U.S.C. § 613(d)(3)