How should socialists engage in coalitional politics? Jack L draws conclusions based on historical lessons and recent experiences in the housing struggle.

In the summer of 2022, it is clear that the forces of reaction are on the rise. Across the world, right-wing movements grounded in reactionary cultural beliefs and dedicated to enforcing undemocratic minority rule are getting organized and winning power. In the United States, while the Democratic Party controls the House, Senate, and Executive office, they and the rest of the liberal establishment seem to have no answer to this problem of right-wing reaction, although they pose it as an existential threat to the US political system. Meanwhile, the socialist and anti-capitalist left is divided (both organizationally and strategically), and appears to be in a post-Bernie, post-BLM decline in organizational capacity and cultural prominence (although the crises stemming from the right-wing minority-rule Supreme Court suggest an opportunity for renewed activity).

In this context of an ascendant right wing and a set of weak and divided alternatives, many socialists have begun thinking about consolidating the left and forming broad coalitions to fight the reactionary right. DSA members across the political spectrum have alliances on the mind, from the Socialist Majority Caucus to the Bread & Roses caucus (with one B&R caucus member writing about the utility of a “membership-based left-wing alliance” like the Richmond Progressive Alliance).

The benefit to a united front of socialists and working class organizations is relatively obvious. The power of socialists and the working class comes from our ability to act together, in large numbers, marching in lockstep toward socialism. However, it is not so obvious how liberal bourgeois organizations relate to this theory of working class power. The Working Families Party, Justice Democrats, Citizen Action, and any number of progressive NGOs are definitely not socialist organizations, and they are definitely not accountable directly to a working class base. All these organizations seem to align with the socialist and working class left on the broad imperatives of “fighting the right” and “building a better life for working class people,” but their divergent class interests suggest an uneasy relationship: where these conflicting interests collide, cross-class alliances may be forced to either split, or to choose between the liberal bourgeois faction and the working class socialist faction. Certain temporary cross-class alliances are inevitable, but how should socialists engage in them without diluting our politics or losing our class independence?

There is also the question of how these coalitions should work. How are alliances forged, and on whose terms? How are decisions made and disagreements resolved: censorship and purges, or democracy and open debate?

Thankfully, socialists have grappled with these problems for over a hundred years, and have left a substantial written record in the process of doing so. This history and these writings can illuminate some principles to take with us as we analyze the present conjuncture and chart a path forward.

Some principles are:

- Fight against the politics of class-collaboration

- Defend the politics of class independence and the freedom to criticize

- Build socialist, working class unity through difference and democracy

Applying these principles to the question of whether or not NYC-DSA should “consolidate” with organizations like the Working Families Party or into coalitions like Housing Justice For All or Invest in Our New York, a few takeaways are clear. None of these organizations are working-class or socialist organizations, and all of them have a history of class collaboration (i.e., siding with the state over working people). While NYC-DSA should enter into temporary alliances with these organizations where shared interests emerge, we must reject any agreement (formal or otherwise) that compromises our ability to criticize coalition members, to build class-independent organizations of socialists and workers, and to fight for our genuinely socialist program. Concretely, this means that these organizations should not be able to influence DSA’s decisions of who to endorse, what campaigns to run, and what programmatic demands to make. DSA should also be prepared to mount full-throated criticisms of these liberal organizations (and the Democratic Party writ large) when they inevitably betray the working class with their class-collaborationist politics, the aim of which can be defined as reconciling antagonisms between the interests of the working class and the interests of factions of the ruling class in favor of the latter. Reconciling factional disagreements in favor of the ruling class obviously weakens the position of socialists and the working class. It follows that compromises on internal decisions (which are at risk of class-collaborationist influence) and public criticism of class-collaboration weaken and demobilize socialists.

On the other hand, DSA should be prioritizing class-independent political work, the aim of which can be defined as the creation of organizations, campaigns and demands that represent the unadulterated interests of socialists and the working class, both in form and in content. This work includes tenant and labor organizing, as well as agitational electoral politics and other work that will help us become a political party for socialists and the working class, united through democracy and a socialist program. With a mass party of socialists and the working class unified in struggle alongside other class-independent working class organizations, the movement for socialism is at its most capable of fighting the right and the liberal bourgeois towards a revolutionary transformation of society towards a socialist democratic republic. This article will explore the historical and theoretical reasons for this strategic orientation toward coalitions.

Fight Class Collaborationism!

Since at least the early 1900s, socialists and the working class have aligned with liberal elements of the peasant, petty-bourgeois, and bourgeois classes to form a “popular front,” typically to fight reactionary forces (tsarism, monarchism, or fascism, depending on the place and historical period).

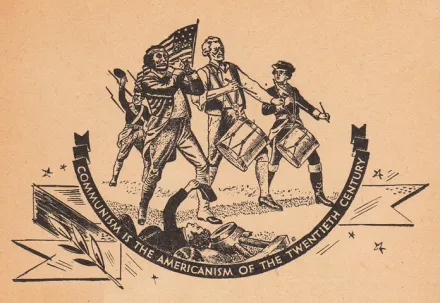

“Popular front” is another term for cross-class alliances. The term originated in the mid-1930s to describe the Comintern’s policy at the time of forming cross-class alliances (or popular fronts) in order to fight the ascendant force of fascism. One relevant example of a popular front is that of the US Communist Party (CPUSA) in the 1930s and 1940s. Per Charlie Post, CPUSA’s orientation stems from the Comintern’s 1935 strategic mandate to build a popular front “with social democrats in the struggle against ‘fascism and reaction,’ … includ[ing] the leadership of social-democratic parties and unions as well as ‘liberal democratic’ capitalists.” In the United States, “[t]he strategy had two central components: an alliance with the democratic middle classes and capitalists through the Democratic Party and a long-term, center-left coalition with supposedly progressive trade union officials in the CIO [Congress of Industrial Organizations].”

Post goes on:

Popular frontism transformed the CP. The party went from promoting self-organization, militant action, and political independence among workers, African Americans, and other oppressed groups to serving as the CIO bureaucracy’s point-men in its drive to tame worker militancy and cement its partnership with the Roosevelt administration.

Most notably, during World War II:

[T]he CP condemned any and all worker attempts to stop speed-up or to oppose workplace despotism as “fascist,” often collaborating with management and the CIO leadership to break wildcat strikes in the defense industry. As the only left current with real weight in the labor movement, the Communist Party’s wartime strikebreaking doomed the movement against the no-strike pledge.

Although the CP’s patriotism won it temporary acceptance among the liberal middle classes and the CIO leadership, the popular front strategy during the war undermined the credibility of the Communists and other radicals among rank-and-file workers and only enhanced the popularity of conservative and anticommunist elements within the CIO.

Post’s overview of CPUSA’s popular frontism in the 1930s and 1940s makes clear that socialists can dilute their politics in order to cement partnerships with liberal bourgeois “partners” in the popular front, which is viewed both as necessary to fight the “existential threat” posed by the right and as useful in broadening the appeal of socialist politics while gaining more access to liberal’s streams of influence and funds. The end result is a class-collaborationist “subordination of the interests of the working class to those of the state,”1 and a decline in militant, independent working-class political activity. This is far from the only example of socialists self-censoring on the terms of the bourgeois liberal statists in a cross-class coalition resulting in a demobilization of class-independent political activity. This phenomena has taken place within the Labour Party in the UK, the PCF in France, and more locally, NYC-DSA in the Housing Justice for All coalition.

In 2020 and at the beginning of 2021, the Housing Justice for All coalition (comprising liberal NGOs, DSA, and a number of autonomous tenant unions with a range of anti-capitalist politics), was united in fighting for an eviction moratorium and the universal cancellation of rent (Cancel Rent!) to address the crisis of housing instability during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in February of 2021, Democratic Party leadership began pushing for a much more business-friendly resolution: means-tested rental assistance and the end of the eviction moratorium. Organizations on Housing Justice for All’s right-wing liberal flank, such as the Legal Aid Society, began aligning with “progressive” Democrats such as Brian Kavanagh in support of this means-tested approach, which, by sacrificing the housing stability of millions of working-class New Yorkers, would allow state administration of capitalist market relations to resume without further delay. Naturally, NYC-DSA and the autonomous tenant organizations began showing up to Kavanagh’s home and to online events to protest this development. These protests were met with disgusted counter-protests from the Legal Aid Society and others in the liberal wing of Housing Justice for All; absurdly, some even went so far as to claim that these protests constituted a campaign of harassment that credibly threatened Kavanagh’s life. While this counter-protest was framed in terms of decency and norms of political civility, functionally it was an attempt by liberals in the coalition to censor the socialist wing of the coalition for criticizing one of their political allies. The fact that Kavanagh was now positioning himself as an opponent of the coalition’s goals to that point was seemingly secondary to certain NGOs’ interest in maintaining cordial relations with an elected politician. After this liberal counter-protest, NYC-DSA decided to limit public criticism of Kavanagh because of his connection to the liberals in the coalition. I know this because I was working on comms for DSA’s Housing Working Group at the time. The end result? With the socialist and working-class wing of the coalition effectively neutered, the state passed their shitty rental assistance bill (with support from Legal Aid and other liberals in the coalition), the eviction moratorium ended, and the more leftist organizations retreated from the coalition to regroup, the bitter taste of betrayal in our mouths.

There is certainly more nuance to both of these stories than can be contained by this account. But the question raised by both is the same: why do cross-class coalitions tend to result in socialist self-censorship and a decline in militant, independent working-class political activity? Karl Kautsky provides some theoretical explanation. Although Kautsky recorded these thoughts in 1904, and is discussing the particular situation of French socialists serving in the cabinet of a bourgeois republican government, his analysis of coalitions between socialists and bourgeois liberals rings true to this day.

In “Republic and Social Democracy in France,” Kautsky writes:

The colossal growth of proletarian socialism made ‘duping the workers’ urgently necessary for the bourgeois republicans – more than ever before. … But they had already given up on formally winning the workers from socialism through these means and shackling the workers to their tatty banner. They were compromised too much and had lost all credibility amongst the proletariat. There was now only one way of exploiting the proletariat’s power for bourgeois ends – to win the socialist parliamentary deputies to carry out those bourgeois policies which the bourgeois republicans had already become too weak to carry out by themselves. Since they could no longer kill off socialism, they sought to tame it and make it subservient to them.

So the bourgeois republicans rely on socialists both to carry out their own policies (which they are too weak to fulfill), and to make socialism “subservient” to their bourgeois goals: at bottom, the maintenance of the capitalist state.

How then do the bourgeois republicans win these socialist politicians to their cause? Through a popular front against monarchism and clericalism, which bourgeois republicans characterize as “the greatest danger to the republic.”

Of course, as Kautsky notes,

In France, the struggle of the revolutionary-minded sections of the bourgeoisie, the petty bourgeoisie, and the proletariat against the Church is over two hundred years old … does this fact alone not prove that the bourgeoisie is incapable of dealing with the Church, and that the proletariat will burden itself with a labour of Sisyphus if it faithfully follows the bourgeoisie in this struggle and acts as its knave?

This cross-class struggle against the Church is doomed to fail, because at the end of the day,

the bourgeois liberal politicians have every interest in the struggle against the Church, but by no means in triumphing over it. They can only count on the alliance of the proletariat as long as this struggle continues. If it comes to an end, their ally will be transformed into an enemy …

Replace “the Church” with “fascism” or with “Trump” and this analysis immediately becomes contemporary. Yes, liberals did join in a popular front with socialists to fight fascism during World War II, but the post-war history of the incorporation of Nazis and fascists into the US state and other liberal states as allies against the rising threat of socialism and the USSR indicates that cross-class alliances will always be temporary, due to the differing class character of these political elements. Do liberals really want the same things socialist do? Of course not. They want to maintain capitalism, and they will always betray socialists to accomplish this end.

Liberals’ commitment to cornerstone values like freedom are also illusory. They are constrained by the contradiction between liberal values and the exploitative nature of capitalism. Indeed, as Lars Lih writes in Lenin Rediscovered,

the bourgeoisie’s interest in political freedom goes down as the proletariat’s interest in it goes up. The bourgeoisie certainly would not mind having political freedom for themselves, and they have no qualms about enlisting proletarian help in getting these freedoms – as long as the bourgeoisie can be sure that the proletariat will not use them in a dangerous way.

Examples of this contradiction resolving in favor of market exploitation can be found throughout US history, from the stain of slavery on US independence (and the continuation of that legacy, through Reconstruction to Jim Crow to the prison industrial complex to ongoing attempts at suppressing the voting rights of Black people) to the fundamentally undemocratic nature of our primary system. On the other hand, socialists and the working class are the protagonists capable of taking the struggle for freedom to its logical end: against the domination of capital in everyday life.

Given this history, should socialists form temporary alliances with liberals to fight the right, or when there is other common ground? Yes, but with no illusions: the post-war alliance between liberals and the fascist, reactionary right reminds us that liberal alliances can and will cut both ways. Liberals and socialists have entirely different class interests, leading liberals to fight the right only insofar as it allows them to regain control of the capitalist state and continue to administer it. This means that, in the United States, socialists must be prepared to loudly criticize liberals (and especially the Democratic Party) for betraying the working class through their duplicitous, class-collaborationist politics putting capital before working people.

It is important to remember Wilhelm Liebknecht and Vladimir Lenin’s guidance here. In his preface to Liebknecht’s pamphlet “No Compromises, No Electoral Agreements,” Lenin, summarizing Liebknecht, states that “the strength of fighters [is] real strength only when it is the strength of class-conscious masses of workers. The class-consciousness of the masses is not corrupted by violence and Draconian laws; it is corrupted by the false friends of the workers, the liberal bourgeois, who divert the masses from the real struggle with empty phrases about a struggle.”

Defend Class Independence and the Right to Criticize!

How then to engage in these liberal-socialist alliances that are fraught with class-based contradictions? It is important to keep two principles in mind:

- Retain working-class independence, and resist class collaboration that subordinates the interests of the working class to those of the state.

- Retain the ability to criticize coalition partners for their class-collaborationist politics and their political horizons that are insufficient for working class liberation; and the right to speak freely about socialist alternatives.

In Revolutionary Strategy, Mike Macnair makes the case for the need to resist the class-collaborationist politics of the popular front’s liberal and social democratic “right” wing:

The right is linked to the state and willing to use ultimatums, censorship and splits to prevent the party standing in open opposition to that state. It insists that the only possible unity is if it has a veto on what is said and done. The unity of the workers’ movement on the right’s terms is necessarily subordination of the interests of the working class to those of the state. Marxists, who wish to oppose the present state rather than to manage it loyally, can then only be in partial unity with the loyalist wing of the workers’ movement. We can bloc with them on particular issues. We can and will take membership in parties and organisations they control – and violate their constitutional rules and discipline – in order to fight their politics. But we have to organise ourselves independently of them. That means that we need our own press, finances, leadership committees, conferences, branches and other organisations. It does not matter whether these are formally within parties which the right controls, formally outside them, or part inside and part outside. This is tactics. The problem is not to purify the movement, which is illusory, but to fight the politics of class collaborationism.

Where there is alignment, socialists can and should enter into temporary agreements with elements of the liberal bourgeoisie. At the same time, socialists must fight to retain both class-independent organization and class-independent politics. What form this class independence takes is a tactical question grounded in concrete situations. But it certainly means avoiding the mistake made by past popular frontists (CPUSA with the CIO, NYC-DSA with Housing Justice for All, etc.) of fudging political differences through censorship on the class-collaborationist right’s terms. When socialists tail a cross-class coalition’s liberal right wing, class-independent political rhetoric is diluted and class-independent organization is demobilized.

As a first-order strategic priority, socialists must always criticize the existing political system and promote independent working-class organization and a programmatic socialist alternative. As discussed above, abandoning this right to criticize has been a fatal flaw in past usages of the popular front, cross-class coalition. To the contrary, in these cross-class formations the socialist’s ability and willingness to speak (both to offer negative criticism and positive alternatives) becomes all the more important. Per Kautsky:

The more the bourgeois republicans tried to dupe the masses of workers by presenting their next goal solely as that of salvaging the republic in association with the bourgeoisie and fighting the Church … the more socialist propaganda had to confront critically the bourgeois aims and means of struggle in order to show: how little the proletariat would gain from these; that the proletarian republic is different from the bourgeois republic; that the proletarian methods of salvaging the republic and fighting the Church are fundamentally different from those of the bourgeoisie; and that social democracy rejects an alliance with the bourgeois republicans, rejects becoming an accomplice in everything that these forces have done and failed at.

So when we are asked to join in cross-class coalitions (to fight the right or otherwise), we can enter into this alliance on a temporary basis, but we must at the same time maintain our class-independent political position and criticize liberals for class-collaborationist duplicity. This is all the more important when temporary alliances are in place because, in these formations, the danger of liberals duping the working class into believing their class-collaborationist politics are the same as socialist class-independent politics increases. This is why DSA must never shy from criticizing the Democratic Party and their liberal bourgeois allies. Even when the shared threat is the force of right-wing reaction, history demonstrates that the liberal bourgeoisie are not ultimately interested in defeating these political forces, only in prolonging the struggle against them so long as it remains useful in its goal of maintaining a hold on power in the orchestrated management of the capitalist state. If Democratic class collaborationism replaces socialist class independence, we will lose the fight against the right and scuttle the chances of an organized movement of socialists and the militant working class. These profound risks necessitate that class collaborationism be criticized all the more thoroughly in moments of temporary alliance.

Build Socialist Unity through Difference and Democracy!

I have focused so far on the topic of cross-class alliances. However, alliances of working-class and socialist formations must also be considered (contrary to cross-class “popular fronts,” the term “united front” was the Cominterm’s phrase to describe the tactic of working class, socialist coalitions, which was enshrined as Comintern policy at the 4th Congress of 1922). The benefits to united fronts are again obvious: socialists and the working class benefit from strength in numbers, marching in lockstep on the basis of shared demands and a common ruling-class enemy, even if everyone in our ranks do not share our analysis to the letter. As in cross-class alliances, working-class alliances must promote class independence and the right to criticize and express political perspectives. However, a distinct benefit of working-class alliances is that while class contradictions (as will be discussed more below, the tension between leadership, which tends to skew middle class, and the working class rank and file) are still a factor, they are nowhere near as fundamental. For this reason, contrary to the temporary nature of cross-class alliances, socialists should aim to form more permanent and more deeply unified alliances with other socialist and working-class organizations.

While working-class alliances are not faced with the same class contradictions as cross-class alliances, Macnair highlights two important contradictions that must be considered.

The first contradiction is between national interests and the interests of the international working class. A united front of the working class in one country must never compromise international solidarity, lest it fall into national chauvinism and subordinate its politics to the national bourgeoisie.

The second contradiction is internal to the coalition of socialists. It is between the working class base and the organizational leaders who are “either members of the intelligentsia/managerial middle class (petty proprietors of intellectual property) by background, or, if they originate as workers, become intelligentsia by training as fulltimers.”2 The problem here “is to find a road to subordinating the full-timers to the membership.”3 The solution? In Macnair’s words,

To retain its character as an effective instrument of the proletariat as a class, a workers’ organisation must have freedom to organise factions within its ranks. Indeed, the struggle of trends, platforms and factions is a normal and essential means by which its differences are collectivised and a unity created out of them. It must be a unity in diversity.

In other words, socialist coalitions (and socialist organizations themselves) need to cultivate a healthy culture of factional disagreement. It is only through debate, discussion and the democratic resolution of these differences that a true unity can be reached. Otherwise, the only forms of unity that can be accomplished—unity through exclusion, refusal to act, and censorship—are forms that weaken the movement of socialists and the working class.

One variation on the cross-class “popular front” and the working class “united front” coalitions is the “broad front:” a coalitional form being promoted by some members of Bread & Roses that generally entails socialists creating working-class organizations (with some elements of civil society that are not working class) fighting for demands or causes that are not explicitly socialist in nature, but close enough to function as a “transition” towards socialism. The argument is that these have the ability to bring in large numbers of people because of their “transitional,” non-socialistic nature. While a much more detailed analysis of broad fronts is called for, there are a few concerns to note:

- As is the case with cross-class popular fronts, these transitional broad fronts tend towards the dilution of socialist politics towards class-collaboration. The history of non-socialist broad fronts emerging from “civil society” are instructive, in that many of these “civil society” organizations are now practically indistinguishable from liberal bourgeois non-profits that have absolutely no mass base to speak of.

- Accordingly, transitional broad fronts also have an unclear relationship towards class independence: while many broad fronts have more of a working class character, because they are not explicitly socialist organizations, they can tend towards the liquidation of socialist politics into class-collaborationist liberal politics (or worse, liquidation of socialists into liberal organizations they have no control over).

- While broad fronts can tend towards liberal liquidationism, they can also tend towards sectarian bureaucratic centralism. This is due in part to the application of this tactic by the relatively small organizations of Trotskyist and other more sectarian tendencies, who assume leadership of these mass-character broad fronts. As Macnair writes in his excellent critique of broad frontist politics:

Broad frontism uses liquidationist arguments, but does not immediately take the form of liquidationism, because in most cases the broad front is conceived as being ‘on the road to’ the construction of a ‘revolutionary party’ – meaning by the latter a bureaucratic centralist group which lurks within whatever broad front its comrades happen to be involved in.

This latter point is why it does not make much sense to criticize those opposing broad fronts as “sectarian:” oftentimes, it is the sectarians themselves who seek to set up broad front-style front groups that they control through bureaucratic centralism!

Again, this is not to say that the broad front form of coalitional politics cannot be effective tactically: merely that an assessment of the concerns around class-collaboration, liquidation and bureaucratic centralism, as well as a commitment to class-independence and organizational democracy (including the right to criticize class-collaboration and talk openly about socialist politics) is called for.

Conclusion

History shows us that coalitions, both of elements within the working class and across classes, are both inevitable and fraught with contradictions and potential pitfalls for socialists. To avoid these pitfalls and strengthen the socialist position through coalitions, socialists must uncompromisingly fight for class independence, the right to critically draw the line between class independence and class collaboration, and a socialist unity forged through debate, discussion and the democratic resolution of factional differences.

These principles must be applied tactically, within a concrete situation and with respect to a specific coalition. The question of detailed tactics is outside the scope of this article, but for now suffice it to say that, before DSA (NYC-DSA especially) enters into lasting partnerships with liberal organizations like the Working Families Party, or deepens our involvement with coalitions like Invest in Our New York or Housing Justice for All, we should conduct an honest and public accounting of these organizations’ and coalition members’ tendencies toward ruling-class collaboration and suppression of dissent. We must understand the extent to which our ability to criticize, promote class-independent politics, and fight for DSA’s program will be weakened. We must draw firm lines in the sand in accordance with these principles: lines on organizational independence (to make our own endorsements and programmatic demands), the freedom to criticize class collaboration, and so on. We also must be willing to leave alliances when those lines are crossed, criticizing these organizations openly and loudly as we walk away. This accounting may seem relatively straightforward for clearly class-collaborationist organizations of liberal-bourgeois politicians (such as the Working Families Party), but it is important to stress two things: first, for many in DSA, this accounting is not obvious at all; and second, it is especially unclear (and all the more important) for broad front organizations and coalitions that are spearheaded by socialists but have unclear mixtures of class-collaborationist and class-independent politics. Without this open and honest accounting of tendencies toward suppression and class-collaboration, and without a firm commitment to class-independent programmatic politics, socialists are likely to weaken our cause through the repetition of our predecessors’ well-documented mistakes.

Fight class-collaborationism; defend class independence and the freedom to criticize! Build socialist, working class unity through difference and democracy!

- Macnair, Revolutionary Strategy, pg 83

- Macnair, 101

- Ibid.