What political lessons can be learned from the failed Bavarian Soviet Republic? Alexander Gallus takes a deep dive into the history of this famous moment from the German workers’ movement and aims to draw contemporary lessons for revolutionary Marxist politics.

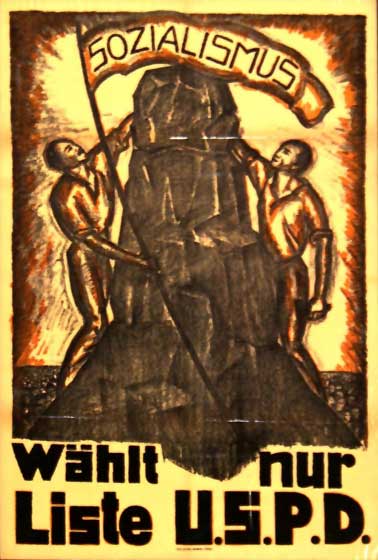

As World War I came to an end, it became clear, contrary to the Kaiser’s war propaganda, that Germany was losing and would concede losses to the Allies. Changes would come and were already coming to Germany. However, the Social-Democratic Party of Germany, which had irresponsibly betrayed its foundational principles to overthrow capitalism and its state order, by supporting the Kaiser’s war, became the main political benefactor of the eventual German Revolution. Discontent and horror at the practical dictatorship of the wartime Army were widespread, and a multiplicitous opposition within the SPD split into an Independent Socialist Party, or USPD. While still small in 1917 at its inception, it was to gain a third of all branches from the SPD within three years. In Bavaria, the Independent Socialists became famous for agitating the January Munitions strike in which 8,000 workers organized in an attempt to thwart military production.

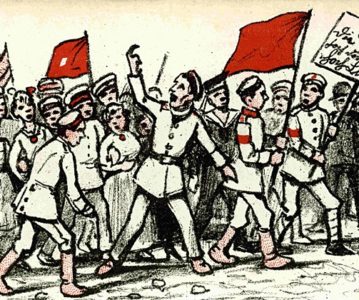

While the USPD had many tendencies and was not certain in its political mission, it became a politically relevant party that genuinely threatened the SPD from the left. While the senseless war which had already been lost continued, zealous Generals still demanded soldiers to fight and give their lives for the pride of the nation. In response to the Navy’s order on October 24th to take to high seas once more, the rebellion of sailors in northern Germany to take over the Kiel navy base instigated what was to become the German ‘November Revolution’. Counterintuitively, it was in conservative Bavaria where, with the SPD dominating the USPD’s smallest local, Germany’s first monarchy was overthrown. Beginning at the expansive Theresienwiese and site of the yearly Oktoberfest, the revolutionary procession of November 7th was planned and instigated by the local offshoot of the SPD, the Independent Socialists, and radicals around Eisner. Having been a powerful leader of the Social-Democratic Party before and at the outset of the war, Eisner fell out with the right-wing leadership of the party over his war-opposition and was labeled a left-wing detractor, later to join the founding congress of the USPD.

The Bavarian revolution spanned from November 1918 to May 1919.

Kurt Eisner had just been released from Stadelheim prison a few days ago. It had been half a year that he had endured in the Bavarian King’s jails for supporting the January Munitions strike. Many of his incarcerated comrades had not. Clara Zetkin and Eisner had mourned deeply over their friend Sonja Lerch’s suicide inside the prison, that fiery woman whom the bourgeois press called the Russian ‘steppe fury’ and understood that “she roused the workers stronger than Eisner”. (Gerstenberger, pg. 295) Every day since the sailor’s mutiny a week before, the tension and excitement among Munich’s people and socialists rose as the size of the demonstrations grew. Two nights ago Eisner felt compelled to send the crowd home, promising more within ’48 hours’. Now here he was, standing in the sunlight under the towering Bavaria statue, looking over the gathering on the Theresienwiese. There were significantly more people assembled here today, by all estimates 10%-20% of Munich’s population.

Auer, the local SPD leader, had been compelled by his members to organize and attend this anti-war and hunger protest on November 7th, assuring the Imperial Minister of the Interior that he would maintain control of the situation. As ever more people came to listen to the speakers it quickly became clear that most had no time to spare for Auer’s empty promises of a future peace and distant socialism, and that the SPD orderlies had no control over the free movement of the crowds. Sailors, soldiers on leave, as well as soldiers who simply left their garrisons, came armed and mixed with the workers. It was Eisner who felt the mood of the crowd and followed it. A soldier’s call to his peers of “All soldiers to Eisner!” is dutifully followed as Eisner’s speaker section fills up. (Schmolze, pg. 89) Discussions about the seriousness of the situation are conducted among the crowd. As the revolutionary conviction and excitement grew, the growing calls of “Peace!” and “Up With the World Revolution” are met with heckles and jeers from the SPD section. There is a moment of silence. The tension is great and only interrupted by Felix Fechenbach’s (Eisner’s USPD associate) decisive call to march on the barracks as had been planned two days prior by the local USPD leadership.

How much longer were they expected to suffer kill and die for the luxuries of the royal families? The winter of 16/17 had starved tens of thousands of Bavarians to death, mostly the vulnerable, young and old. And now with the Spanish flu raging at the start of the next winter the nation was still sending all its resources to the front. They had enough. Today they were not going home. Following Fechenbach’s call and the lead of the group around Eisner, the procession marches northwest. Barracks after barracks sees the soldiers join the revolutionary march and the police pressed against the wall. Knocking on the doors of the ‘Türken barrack’ no one opens and the revolutionaries expect resistance when suddenly a young conscript’s head pops out of an upstairs window and asks “What’s up?”. “What do you think is up? Revolution!” (pg.91)

In response, the Imperial Bavarian military was trying not to lose total control over their Bavarian regiments. After tens of thousands of Munich and surrounding Army forces proved rebellious they had only two reliable divisions left to send to Munich, one being Prussian. A Bavarian division en route to the Alps of the Tyrolean war front was turned around midway and sent back towards Munich. On its way back to mute the burgeoning worker-peasant and soldier councils, this Bavarian division’s shock troops were met not by one but two whole revolutionary automobiles which successfully disarmed them. The incoming Prussian division was similarly met with red guards laced with belts full of hand grenades and rifles slung over their backs, on the outskirts of Munich, informing them not entirely soberly that “Brothers, Comrades, it’s over with the Slavery – don’t raise your weapons against your brothers, throw them away!” (pg. 120) And in unison they did.

Of all states, the Bavarians were the most conservative of Germans, yet they were the first to overthrow the dynasty and proclaim the Republic, in which the revolutionary councils were to take a leading role. While the Munich Independent Socialists (USPD) indeed had very few members in October of 1918 (Morgan, pg. 156) there is reason to believe that the release from prison of the popular January strike organizers, including Eisner and his colleagues (as well as the USPD left around Fritz Sauber and August Hagemeister), led to a rapid increase in worker membership, numbering in the multiple thousands by the time of the revolution. The party local had numbered in the thousands earlier that year, and now the size of the demonstrations and participation of workers, and especially soldiers, grew exponentially every other day in the week since the prisoners’ release.

After the idealistic intellectual leaders successfully took power, the Bavarian November revolution had the historic fortune of firstly being underestimated, and secondly evading immediate military repression. Having been mostly composed of bohemian intellectuals and poets which gathered at pubs and cafes, the group around Eisner and himself (which included a popular blind peasant leader) were apparently significantly out of touch with the realities of politics. Being hopelessly outnumbered by the size of the SPD, the USPD had an ill-fated future if it was to rely on the working class to successfully wield power. The strength of Eisner’s personality, however, dedication to pacifism, intellectual ability, and radical turn to the revolutionary mood of the time all resulted in his popularity; his relatively uncontested stature among revolutionary socialists and rebellious workers in Munich resulted in a situation where there was no serious socialist rival to decide the course of the November revolution. This is, at least, so far as existing historical record is concerned.

Invited to Berlin in 1898 by Wilhelm Liebknecht to improve qualitative content, Eisner’s chief editorial position at the SPD party newspaper Vorwärts ended after 5 productive years when he refused to publish two polemical statements by then party chair August Bebel, who reacted with a healthy temper. (Gerstenberger) Refusing to accept the reality of the harshness and skullduggery of party politics, Eisner moved back to Bavaria to write about the virtues of a libertarian socialism and poetry, as well as warning against a coming war in the Bavarian Social-democratic newspaper. While not being unjustly labeled as a revisionist by the Orthodox Marxists of the SPD, Eisner’s views fit no existing mold. Alongside his colleague Karl Kautsky, Eisner energetically countered Bernstein’s views that socialism could not be scientific and that the party ought to focus on the betterment of workers’ lives in the present instead of distant social goals.

Retaining that a scientific socialism was vital to the worker movement, Eisner’s personal philosophy was however influenced by the “ethical” ideas of Kant and hence differed with Kautsky’s principally causal moral, implicit in the philosophy of historical materialism. After taking the city of Munich by storm and holding a vote in the Mathäserbräu Beerhall on the night of November 7th, the revolutionaries elected Eisner to head the new government. His signed public proclamation was printed on the 8th, including, amid phraseology, that “order will be maintained by the worker and soldier councils”, and, “that the security of persons and property is guaranteed”. (Weidermann, pg. 23)

While the national USPD in its majority at the time of the November revolution certainly rejected capitalism and aimed to replace it with “socialist construction” (Morgan), Eisner’s group thought it better under the circumstances not to verbalize this traditional principle of the workers’ movement once in power. The egregious logic of this example points towards a strategy of appeasement to the authority of the SPD and in this case the actual owners of property. The SPD, as a matter of course, had a dedication to the governance of a capitalist constitution. Instead of denying legitimacy to the wishes of the bourgeois ruling class and SPD leaders, on the basis of their murderous betrayal of principle and irresponsibility, no thorough challenge to the authority of the social-democratic leaders was posed. This meant that when it actually came time for the USPD to govern (if one can call it that, as it was so without plan or routine) the Bavarian council republic ended up asking the SPD to occupy half the government’s ministries.

Although Eisner genuinely strived towards an international rule of councils, he saw no alternative to inviting the SPD if peace was to prevail. Peace at any price, that was Eisner’s mission, even if it meant more workers had to endure being ruled by those who had destructively sold them out. Consequently, the Independent government let itself be dominated by the majority Social-Democratic ministers, who turned to the existing bourgeois-monarchical bureaucratic apparatus for help. (Beyer, pg. 21) The Eisner government thereby threw itself into political paralysis, with hopes that the heterogeneous array of over 600 councils would spontaneously act to help or that the “struggle for the souls” would bear fruit and (almost divinely) intervene. What resulted was a dysfunctional and powerless government, where no one party (neither the alliance of the SPD with the bourgeois-monarchy, nor the USPD and councils) was able to exercise power. The USPD’s hope in councils acting to successfully challenge the dominance of the SPD had failed.

Even dominant soviets or councils, however, in and of themselves clearly don’t lead to successful worker government. First, one should be aware that worker councils initially appeared mostly at workplaces with very large workforces like factories, where large strikes led to sit ins, sit ins to committees for workplace occupation and their interconnection. While frequently effective at the management of workplace production, the efficacy of a system of councils for regional, or even nationwide governance, hinges not on the abstract desirability of workers having more direct involvement in deciding production and their representation, but technical knowledge and the political question. Simply being involved in the act of producing a commodity in return for a wage does not indicate one’s level of education or understanding for what is necessary and beneficial for the working class programmatically. There is also the problem that councils of large and smaller industry, where unionization is high and militant tradition strong, leaves a large part of the population outside the realm of the decision-making process and representation.

The downward trending growth of capitalist production, its tendency to be more and more artificially upheld and the developing “fourth industrial revolution” have seen through western “deindustrialization”, making the vision of soviets universally liberating us from capitalism thoroughly blurred. Naturally, pursuing a hopeful policy of creating councils and pushing it on the mass of people (or rather, pushing the mass of people on to councils…) could result in their more widespread creation beyond large industry etc. If these soviets were more widespread, it would however already imply a significant influence of proletarian ideas on the mass of people and yet still leave the flaws of councils unaddressed. Romanticizing “direct democratic” worker councils as a vehicle for revolution not only is a cheap attempt to tackle the task of representation, it is a dangerous ideal and a potentially fatal mistake for Socialists to engage.

National Assembly elections of late January 1919, although a disastrous humiliation for the USPD, showed that almost 40,000 of the Munich population voted for the party. (Beyer, pg. 42) By this point, while the local USPD right pressured Eisner to step down, the left removed themselves from more party activity. Instead of utilizing the newly won unprecedented freedoms like those of the press and challenging the party’s failed Eisner-leadership from the left, Sauber and others chose to abort the struggle for leadership of members and dived into the councils, later to join the KPD’s adventurism. The experience of many socialists within councils enthralled them at the perception of having found a mass organization of direct democratic control. But in reality, these councils, which were bestowed with so much hope, were nothing more than impotent theaters of mere congregation absent an actual political struggle for authority. The Bavarian Imperial Army officers understood this docile and manipulatable vulnerability of the popular councils, calling on the help of SPD men and soldiers in attempts to control and project their power through them. (Schmolze; Beyer) The diminutive KPD’s founding congress cry of “All Power to the Councils!”, in this light, appears perhaps as delusional as the politics of Eisner’s government.

Leading up to the January electoral defeat, Eisner was increasingly pushed into insignificance by the reality of class struggle. The SPD’s open trend to the right was “countered by a trend to the left among the militants of all the socialist parties, especially in Munich. The Independents, pulling away from Eisner’s moderating influence, consolidated their alliance with the groups to their left, especially after the Berlin disturbances of early January, and the activity of all these groups increased” (Morgan, pg. 161) As Bavaria did not yet have a Communist organization until December 11th with the local emergence of a few inexperienced Spartacists, most of the working class discontent either ran into the befuddled hands of anarchists like Mühsam, politically disinterested syndicalists or isolated communists.

For up to four months Bavaria was in this particular state of paralysis. Whereas Munich was to become the hotbed of right-wing extremism over the next twenty years and the birthplace of Nazism, Bavaria, unlike the rest of Germany, did not yet have an organized Freikorps (mercenary paramilitary group). The bourgeois had failed to organize a counter-revolutionary force in Bavaria for months, turning to the SPD for help in building a “citizens” militia forming as late as December 27th. This maneuver was struck down, and dozens of its members arrested, after USPD delegate Ernst Toller reported on its plans to machine gun the ministry building of Eisner.

Suspended in this fluid and economically unresolved situation, where the Proletariat were tied by the hip to class collaborationists (as in the rest of Germany), little record of an organized public opposition to Eisner from the left exists within this period, although spontaneous actions such as the December occupation of half-a-dozen slanderous bourgeois newspapers did occur (Schmolze pg. 189, organized by soldier council head Sauber [USPD] and others who began a loose, council communist movement). Kautsky himself (perhaps not surprisingly) did not challenge the illusory zeal for and hope in councils of his party’s left, saying in the same breath as defending the genuineness of the SPD’s revolutionary posturing, “…their [the councils’] control made it possible for the old state apparatus to continue to function without bringing about the counter-revolution.” (Kautsky pg. 3)

Systems of communication among the local USPD and communists were unfortunately extremely poor. While numbering at half a dozen Bavarian newspapers later in the year of 1919, the USPD’s own newspaper in Munich, “Die Neue Zeitung”, was founded on December 20th of 1918. (Beyer pg. 35) As a tool of Eisner and those nationally regarded as the party center, it refused to follow the dominant social-democratic agitation against the Spartacists. Proclaiming their paper’s mission to ‘fight against the press’, against bourgeois defamations and prejudices, the Bavarian Independents’ efforts were the most successful of all the country, numbering only a few hundred members for most of 1918, to 40,000 by September of 1919. The success of USPD locals in winning over SPD members was seen principally there where daily papers were established, as the researcher Hartfried Krause shows.

Using Marx to justify the view that capitalist industry had to be rebuilt before socializing it, to then “grow into socialism”, Eisner’s revisionism was never deconstructed before the Bavarian public. To his credit, however, as the political situation in Berlin became more desperate and the Bavarian left radicalized, Eisner’s later statement in support of the workers’ growing frustration and council movement’s desire for power, was, “We have no more patience to push our dreams of Socialism into the distant future; today we live and today we want to act” (Schmolze pg.201) Within this environment of the absolute freedom of the press, a lack of clear proletarian leadership, nor an armed working class, the bourgeois inciters were the benefactors. The Thule society and other splintered anti-semite and nationalist groups flourished in Munich, preying on the ignorant and fearful. One of these pre-fascist types was Count Arco von Valley who wrote in his journal “I hate Bolshevism, I love my Bavarian Volk […] he [Eisner] is a Bolshevik. He is a Jew, not a German. He betrays the fatherland — so…” (Schmolze, pg. 228) On his way to declare his official resignation, after being forewarned by his associates not to walk from the Ministry over the public street, Eisner was shot twice from behind and immediately dead. It was to be the first shots of the reaction, instigating the second stage and radicalization of the revolution of Bavaria. For now, however, it was the Social-Democratic party which was preparing counter-revolution.

[… to be continued]

References:

Gerstenberger, Günther. Der Kurze Traum vom Frieden. Germany, Hessen: Verlag Edition AV, 2018

Schmolze, Gerhard. Revolution und Räterepublik in München 1918/19 in Augenzeugenberichten. Germany, Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1978

Morgan, David W. The Socialist Left and the German Revolution. UK, London: Cornell University Press, 1975

Weidermann, Volker. Träumer. Germany, Cologne: Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2017

Beyer, Hans. Die Revolution in Bayern 1918-1919. East Germany, Berlin: VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1988

Karl Kautsky, Das Weitertreiben der Revolution, Berlin, Freiheit, No. 79, 29th of December 1918