Andrew Smith argues that the USSR’s relation to Palestinian national liberation was more about realpolitik than earnest dedication to the cause of the Palestinian people.

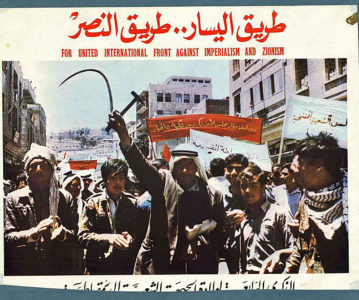

The relationship between the Soviet Union and the Palestinian national liberation struggle was a highly ambivalent one set against the backdrop of the Cold War. As the Western and Eastern Blocs vied for influence in the Middle East, the Soviet Union proclaimed in the late 1960s that they would resolutely support — materially, diplomatically, and ideologically — the Palestinian people in their war of national liberation, and the broader Arab world against “imperialism and Zionism.” This position, they proclaimed, stemmed from the Marxist-Leninist positions of “proletarian internationalism” and “self-determination of nations.” However, like much of Soviet foreign policy, reality was far different from rhetoric. Upon further examination of Soviet actions toward Palestine, this supposed solidarity with Palestinian revolutionaries was not one of revolutionary internationalism and anti-imperialism, but was, in fact, simply a cover for the realpolitik the Soviet Union utilized to make the Middle East one of its spheres of influence, with the Soviet Union often sidelining Palestinians in favor of keeping allied Arab states within their orbit. Even at the height of Soviet aid to the PLO, the relationship was one of conditional love and, in some ways, borderline cruelty in its pragmatism.

To gain an understanding of Soviet rhetoric concerning Palestine, one must take into account two major tenets of Marxist-Leninist doctrine: the concepts of proletarian internationalism and self-determination of nations. Proletarian internationalism is the notion that, as Marx and Engels said in the Communist Manifesto, “the working man has no nation” and that the interests of the international proletariat take priority of the interests of one’s own nation. At the same time, Marxism-Leninism espouses that all nations have a right to determine their own destiny without fear of intervention from imperial and colonial powers. From its birth, the Soviet Union — at least ostensibly — believed that it, as a nation, had a duty to stand in solidarity with the anti-colonial and national liberation struggles of the Third World.

According to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s official policy, Zionism was “the most reactionary variety of Jewish bourgeois nationalism” and “distracts Jews from class struggle because it treats Jewish workers and bourgeoisie as both having the same interests.”1 While Jews were an officially protected national minority with their own small autonomous oblast in the Russian Far East and antisemitism was heavily disdained in Soviet discourse, Jews were not seen as a coherent nation-state with distinct ties to a particular region of the world. As such, the idea of a Jewish homeland within Palestine was, in a Soviet Marxist framework, completely unacceptable and could only act as an imperialist project for capitalist powers against the colonized Arab peoples. Soviet Jewish organizations, following the party line, were resolute in their opposition to Jewish migration to Palestine.

After World War II, however, pragmatism trumped principles. Reeling from the Holocaust and still unsure of how to deal with the massive displaced populations of Jewish survivors in the Eastern European states it had liberated from Nazi rule, the Soviet Union decided to recognize the State of Israel in 1948. The motive for this was two-pronged: the first reason was to appease the United States. Soviet leader Josef Stalin knew that the alliance with the West forged during the war would not last much longer, that a long Cold War was coming, and that he needed to buy time to prepare for the protracted confrontation. The second reason was to push the British out of Palestine and keep in check any further British or French colonial ambitions in the Middle East. Nevertheless, the Soviets were strong believers in the need for both a Jewish state and an Arab state with Jerusalem serving as the capital of both, and they opposed the mass expulsion of Palestinians from Israel in al-Nakba of 1948.2

The honeymoon period between the USSR and Israel was extremely short-lived. By the end of the year, 200,000 Jews had emigrated from the USSR and Soviet-occupied countries to Israel. The Soviets quickly feared strengthening Zionist organizations within their borders, and in 1949 the Soviet press denounced Zionism once more as “bourgeois nationalism.” Diplomatic ties between the USSR and Israel were broken in the 1967 war.

Across the 1950s and ’60s, with Nikita Khrushchev at the helm of the Kremlin, Moscow threw an enormous amount of investment and advisement into Egypt and Syria, particularly during the United Arab Republic period, as well as Iraq to a lesser extent. This was primarily done in order to curry the favor of these countries’ governments and convince them of the superiority of a socialist-based economy and the advantages of staying within the Soviet camp, albeit keeping class struggle by local communist parties on the sidelines of this broader strategy. For nearly fifteen years, the Soviet Union kept the Palestinian question as a minor one of little consequence to their broader Middle Eastern strategy, with only the occasional statement about the “legitimate rights of Palestinian Arabs” to a right of return.3

In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization was founded in Cairo, Egypt, as a coalition of Palestinian armed groups and political parties dedicated to the liberation of Palestine from Israeli occupation. While most anti-colonial and national liberation organizations during this period were greeted with enthusiasm by the Soviets, the proclamation of a new chapter in the struggle for Palestinian self-determination was met with icy silence. The Soviets, it seemed, could not have cared less about the foundation of the PLO, and in UN meetings concerning the matter would only speak about the problem of Palestinian refugees and the right of return for Palestinians to their ancestral lands.4 If one were to take the USSR’s anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist credentials at face value, one might find this silence around the matter to be puzzling.

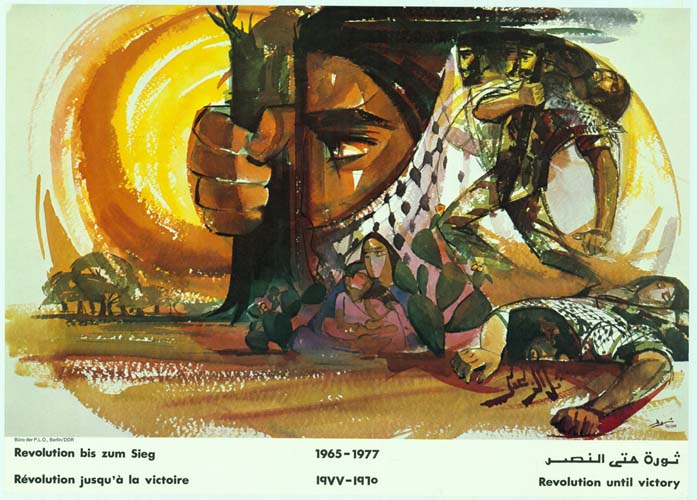

The warming up of relations between Moscow and the Palestinians was extremely gradual. The Soviets began to grant scholarships for members of the General Union of Palestinian Students and the General Union of Palestinian Women to study at universities in the USSR. However, even as late as the end of 1968, the Soviets openly chastised the PLO. Groups like the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, despite themselves being Marxist-Leninist organizations, were particularly criticized for being too close with the Chinese and for their guerrilla warfare tactics, which were labeled “adventurist” and “ultra-leftist.”5 Indeed, nations like China, Cuba, East Germany, Romania, North Vietnam, and even North Korea were more happy to supply material aid to the PLO and were more vocal in their support of the Palestinian national liberation movement at large.6 Nearly all early PLO delegations to Moscow were neither officially hosted by the Soviet state nor by the Communist Party, but by the “Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee” in order to maintain an appearance of a diplomatic disconnect, where support for the Palestinian struggle arose from Soviet citizens who were party activists, not from state conduits.7

It was not until the defeat of the Arab states in the Six-Day War of 1967 that the Soviets realized that the PLO could become a useful tool in countering Israeli — and thus, by extension, US —aggression against their three main Arab client states. In 1969 the Soviets officially hosted PLO leader Yasser Arafat at a reception for Egyptian president Gamel Abdel Nasser, whom he was accompanying on the journey.8 This trip to Moscow by Arafat still did not seal the deal, however — the Soviets acknowledged the PLO’s existence but did not recognize it as the international representative of the Palestinian people. Indeed, when the Syrian Communist Party began to enthusiastically back the PLO in 1971, Moscow almost immediately told the SCP to cease such endorsements and bluntly brushed off any discussion of Soviet support for a new Palestinian homeland. The establishment of serious Soviet-Palestinian ties was further stalled when the Palestinian Black September Organization murdered eleven Israeli athletes and diplomats at the 1972 Munich Olympics, an event which the Kremlin strongly condemned and implicated the PLO in being complicit in.9

By 1974, after the defeat of the Arab states once more in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Soviets realized just how desperately they needed the PLO within their Middle East machinations, and began to treat the PLO as the de facto representative of the Palestinian people on an international level (although they did not officially declare this until 1978, in response to the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt).10 Egyptian president Anwar Sadat began to cool relations with the Soviets after the Yom Kippur War and made significant overtures toward the US that same year. Without Egypt in its orbit and their relationship with Syria also strained, the Palestinians seemed like the logical choice as a group to support to keep Israel in check.11

With the friendship between the Kremlin and the PLO finally cemented after almost seven years of protracted back-and-forth, the Soviets maintained a clear policy: that the goal of any Palestinian national liberation struggle they supported would result in a two-state solution. The PFLP and DFLP’s refusal to relinquish their demand for the dismantlement of Israel and for a multinational socialist republic to take its place was admonished by the Soviets, who firmly planted their support in both rhetoric and financial/military aid behind Fatah, Arafat’s party which commanded the majority of the PLO. Fatah was also important to the Soviets not just because Fatah was the largest faction in the PLO, but because it was also the most likely of the PLO parties to be conducive to a two-state end to the conflict. Furthermore, Moscow understood Fatah as the “bourgeois-nationalist” faction of the PLO most likely to lean towards the West in the distant future; as such, Fatah became their biggest ally and their greatest liability in establishing themselves as allies of the Palestinian people.12

When the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975, the Soviets found themselves juggling three allies now at odds with one another: the Syrians, the PLO, and the Lebanese Communist Party. During the first year of the war, the Soviets were comfortable in the ability to support the PLO-LCP united front.13 With Syria’s intervention into the conflict in 1976 resulting in the bloodshed of Palestinians, however, the Soviets began to feel a great sense of confusion and discomfort. Soviet newspapers such as Pravda began issuing criticisms of the Syrian role in the conflict and the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee released a statement calling on all progressive forces in the region to support the Palestinians. Leonid Brezhnev, then General Secretary of the Communist Party, sent a letter to Syrian president Hafez Assad demanding a withdrawal of all Syrian troops from Lebanon. When Syria refused to back down from its commitment to Lebanon, however, Moscow relented, deciding that it had little to gain from the situation. From 1977 onward, the Soviets kept a mostly hands-off policy toward the Lebanese crisis, pulling away aid from all sides after realizing that taking a position in the fight could be a liability to them.14

Despite the Soviet Union’s abandonment of the PLO in Lebanon, the two sides continued to work with each other in other endeavors, with the Soviet Union hosting a major official PLO delegation in November of 1978.15 After the Camp David Accords, the Soviets began to escalate public rhetoric in support of the PLO and to paint itself as the great ally of the Palestinian, and other Arab, peoples. The Soviets spoke of being “consistent advocates of the Arab people”16, began throwing even more financial and military aid toward Fatah, and recognized the Palestinian Communist Party’s induction into the PLO in 1982.17 In 1983, Communist Party leader Yuri Andropov brokered a deal between the PLO and Syria in Lebanon that staved off further bloodshed between the two parties.18 Finally, it seemed, the Palestinians had found a true friend in the Soviet Union.

With the rise of Gorbachev in 1986, Arafat and Gorbachev realized that both the USSR and PLO were in significant decline in terms of prestige in the Middle East: both had alienated many of their Arab allies and failed to construct new relations with other political trends within the region. The communist movement in the Arab world was nearly moribund, and the Soviets had only one socialist ally in the entire region: the relatively quiet and non-strategic South Yemen. While the PLO still received praise in the press of left-wing parties around the world, Arab state sponsorship of the Palestinian cause was at an all-time low due to the PLO’s refusal to relinquish the use of terrorism as a major tactic in armed struggle against Israel. Now, more than ever, it seemed that the USSR and PLO needed each other on the global stage if both were to maintain relevance in the region.19

In 1989, as the USSR was unraveling and communism was collapsing in the Eastern Bloc, the Soviets and the PLO seemed to continue their firm relationship and the Soviet Union seemed guaranteed a decisive role in the peace process, particularly with the 1988 First Palestinian Intifada uprising having made headlines due to its dramatic scope and scale. At first, Moscow was at first content with the Intifada, primarily due to it being a spontaneous uprising not initiated by the PLO, but the Soviets soon grew uneasy as the PLO became more tied to the uprising and Gorbachev gradually became more interested in ending to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through negotiations rather than armed struggle. Mixed feelings toward the trajectory of the Palestinian national liberation movement is noticeable in the Soviet press of the time, which extensively covered the Intifada but did not paint it in an enthusiastically positive light. The Intifada was, however, spun as a symptom of America’s insufficient work within the peace process: indeed, coverage of the Intifada was more anti-American than it was anti-Israel or pro-Palestine, and was meant to tout the USSR as the only trustworthy broker for peace in the region.20

Rekindled ties between Moscow and the PLO soured quickly in 1990 when, in response to rocky relations between the PLO and the US, Arafat aligned the PLO with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. When the Gulf War broke out in August of the same year, the USSR backed the anti-Iraq coalition forces, causing a great deal of consternation within the PLO. Indeed, the resentment towards the Kremlin became so sharp that when the August 1991 putsch by Party hardliners against Gorbachev was attempted, the PLO hailed the abortive coup against “the renegade” Gorbachev. The Palestinians were no longer simply displeased or disappointed: they felt unrelenting antagonism and antipathy towards the Soviets.21

With the USSR fully in tatters, in September of 1991 Gorbachev set into motion a policy of allowing full freedom of immigration for Soviet Jews to Israel. By the end of the USSR’s existence on December 25, 1991, the PLO viewed the Kremlin as an enemy of the Palestinian people, with the PLO seeming to only understand Moscow’s true intentions toward them once the Soviet Union was on its deathbed.22 In the end, it is clear that the Soviet Union was never truly the “consistent advocate” of the Palestinian people that Moscow so enthusiastically touted in its media. Indeed, compared to their support of national liberation struggles like East Asia and Africa (e.g. Vietnam, Laos, Angola, Mozambique, etc.), the Soviet Union’s support of the Palestinian national liberation movement is glaringly half-baked. It is an obvious fact that the USSR was a fair-weather friend only interested in realpolitik, and without concern for the well-being of the Palestinian people, much less for a legitimate peace in the Middle East.

- Bolshaya sovetskaya entsiklopediya (The Great Soviet Encyclopedia). 3rd ed., s.v. “Sionizm.” Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya, 1973, p. 282.

- Galia Golan. Soviet Policies in the Middle East: From World War Two to Gorbachev. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991, p. 37-39

- Galia Golan. The Soviet Union and the Palestine Liberation Organization: An Uneasy Alliance. New York, NY: Praeger, 1980, p. 5.

- Golan, Soviet Policies, 110.

- The Soviet Union and the PLO, 7-8.

- Paul T. Chamberlain, The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015, 61-64.

- Golan, The Soviet Union and the PLO, 26.

- Soviet Policies, 110.

- Ibid., 110-111.

- Ibid., 110-111.

- Roland Dannreuther, The Soviet Union and the PLO. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1998, 31.

- Chamberlain, 221.

- The Soviet Union and the PLO, 180.

- Ibid., 208-209

- “Otyezd delegatsii.” Pravda, November 2, 1978, 9.

- “Arafat-Brezhnev Meeting.” Journal of Palestine Studies 11, no. 2 (1982): 184-86.

- Soviet Policies, 274.

- Yevegeny Primakov. Russia and the Arabs: Behind the Scenes in the Middle East from the Cold War to the Present. New York: Basic Books, 2009, 240-245.

- Dannreuther, 143-144.

- Ibid., 160.

- Ibid., 169-170.

- Ibid., 171.