Before the rise of the Soviet Space Program, utopian visions of space travel existed alongside serious scientific work to make it a reality. Donald Parkinson explores the culture of space exploration that existed both before and after the Bolshevik Revolution and how it laid the groundwork for Sputnik.

Common sense tells us that the Soviet Space Program was primarily a state project, an outgrowth of the military sector aiming to create ballistic missiles that culminated in Sputnik and launched what is commonly known as the “space race”. In this interpretation, the space race was merely a geopolitical competition between two governments to overpower the other in terms of technological achievements that would also give the respective states a military edge. Some, such as Deborah Cadbury in her book Space Race, reduce the competition to traverse the cosmos to a battle between two great scientists, Wernher Von Braun, and Sergei Korolev. Yet to reduce the Soviet aspiration to leave the Earth’s atmosphere to a mere military operation, or two men’s personal ambition, would ignore the cultural roots of the Soviet Space Program that date back to the pre-revolutionary period of the late 19th century, where a group known as the “Cosmists” combined techno-utopianism with occult spirituality to develop a vision of colonizing the cosmos. After the Bolshevik Revolution the idea of space travel was popularized by the creation of various Cosmonautics Societies, with or without state approval. The Bolshevik Revolution, and its promethean drive to conquer nature in the name of human progress, allowed a flourishing of ideas that existed on a spectrum that ranged from crankery to brilliance. While such cultural experimentation ultimately was repressed if not shut down by Stalin’s “cultural revolution” and purges, the utopian cosmonauts of the 1920s represented a truly revolutionary culture. Within this unique culture, the Cosmists stood out. Their uncompromising prometheanism went beyond Bolshevik hopes and preceded the mid-century Soviet fascination with space. By examining the ideas of the Cosmists we can see in action the utopian imagination unleashed by revolution, one that is in continuity with past trends of thought yet accelerated to cross new boundaries.

The first state-subsidized rocket program in the USSR started in 1933 through cooperation between the Red Army and amateur space enthusiasts. This collaboration represented a general contradiction within the Soviet space program between Cosmic dreamers and military men. The military was interested in using technology to expand the military capacities of an isolated Soviet republic, which had chosen a course of “socialism in one country” in which international isolation necessitated an industry dedicated to arms build-up.1 The other side of this collaboration involved a wide range of enthusiasts of the Cosmos, who continued and amplified a Russian tradition of fascination with space flight, with ideas ranging from scientifically groundbreaking to occult mysticism. This colliding of military interests and promethean utopianism was described by the historian of the Soviet space program Asif A. Siddiqi as the “bridging of imagination and engineering”. Much has already been said about the role of engineering in the Soviet Space Program, but hardly anything has been said about the role of imagination.

The focus here will be on imagination: those who dreamed of an escape from Earth’s gravitational pull to pierce the atmosphere and enter unknown frontiers. Before the Bolsheviks ever took power, space travel existed as part of the popular consciousness in Russia, although in a relatively subdued sense. Jules Verne’s popular novels serve as the first major example of the presence of space travel in the Russian consciousness. Verne’s first novel translated into Russian appeared in 1864, going on to be one of the most popular foreign novelists in Imperial Russia. French novelist Camille Flammarion’s astronomicheskii roman (astronomical novels) also added to the allure of space, contributing to a popular fascination with Mars through their musings regarding life on the planet. Alexander Bogdanov, a Bolshevik himself, wrote the great Russian novel Red Star about an advanced socialist society on Mars in 1908. Bogdanov’s version of the astronomicheskii roman serves as a sort of prophetic vision of how the imaginative desire for space travel would merge with the actual construction of an (attempted) socialist society that would itself travel the stars.

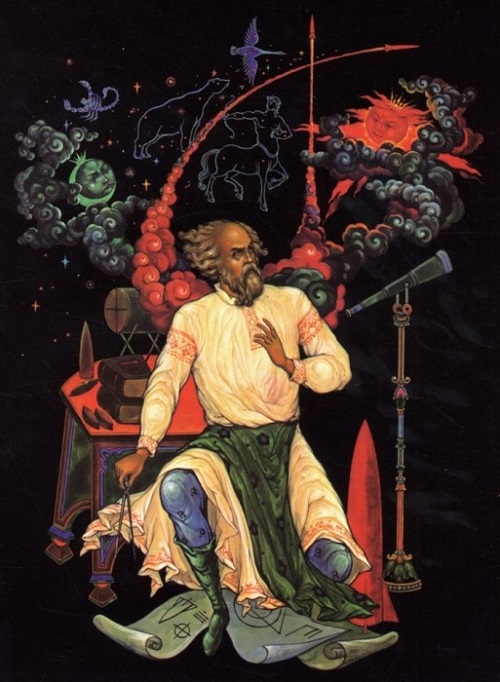

The topic of space travel in Imperial Russia was not limited to the flights of fancy of science fiction writers, however. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky wrote science fiction novels but also did serious scientific work on questions of space travel, writing: “If a man is a participant not only on Earth, but also in the Heavens, then the influence of free space should be of special interest.”2 Tsiolkovsky’s first major achievement came in 1903 when he mathematically proved that a rocket could reach escape velocity using liquid fuel, using a model that related the three variables of changing rocket speed: rocket mass, propellant mass, and the exiting velocity of the gas. While his work was under-recognized at the time, this paper would go down in history as the first rigorous proof that space travel was within the realm of possibility.

Tsiolkovsky went beyond scientific tracts and developed his own philosophy of the cosmos. For Tsiolkovsky, the mystical and the scientific would be combined without contradiction, taking from German occultists like Carl du Prel as well as Darwinian natural selection and, of course, the Christianity of the Russian Orthodox Church. At the core of his thought was an attempt to reconcile the scientific worldview with the Christian worldview and prove the consistency between Biblical worldviews and science. Through these attempts to develop a whole philosophy of cosmic belonging, Tsiolkovsky took part in the creation of the philosophy of Cosmism, a form of promethean mysticism that strove to take the transcendent qualities of religion in a scientific direction.

Another who took a leading role in the development of Cosmism was Nikolai Fedorov who would die in 1903, leaving behind the epic Philosophy of the Common Task. Fedorov’s philosophy was religious in scope and claimed that the unifying goal of humanity was to become immortal and to resurrect the dead. Christianity had a strong influence on this philosophy — if man was to emulate Christ, then man must rise from the dead. One can see a rough parallel with Marxism in this philosophy: humanity must develop society and the productive forces in order to flourish as human beings and overcome the limits of both class society and nature itself. Another parallel ideology is transhumanism, which is more associated with Silicon Valley libertarianism. Like the transhumanists, Fedorov aimed to utilize technology in an unprecedented way to achieve the abolition of death itself. Technology was de-secularized in Fedorov’s philosophy and framed as a means to achieve mystical ends. Fedorov also saw astronomy as a sort of master science of which all others, especially biology, were subsets. The mastery of astronomy would also mean the mastery of biology, which in turn meant that those once dead could live again and transform the universe in a human image.3 Here we see a strong link between immortality and space travel: before conquering the cosmos, mankind must conquer death itself. To traverse the stars for such distances death cannot become a barrier to the cosmonaut’s journey. Fedorov would greatly influence Tsiolkovsky and both were key in developing the philosophies of Cosmism. Combining Fedorov’s drive to end mortality and his own visions of traversing the cosmos, Tsiolkovsky wrote in 1912:

“In all likelihood, the better part of humanity will never perish but will move from sun to sun as each one dies out in a succession. Many hundreds of millions of years hence we may be living near a sun which today has not yet even flared up but exists only in the embryo.”

When Fedorov died in 1903, the Cosmists were only beginning to develop their thought. The collapse of Czarism and the Bolshevik Revolution would give new life to the Cosmist vision. While one could see the mystical tendencies of the Cosmists, often dealing in Christian themes and agrarian folklore for inspiration, as at odds with the militant rationalism of the Bolsheviks, the Cosmists shared aspects of the Bolshevik worldview as well. Like the Bolsheviks, the Cosmists saw technology as a tool for human liberation, a means to move past old barriers and achieve greater states of social being. For both the Bolsheviks and Cosmists, technology offered a way to conquer the barriers of nature rather than blindly follow them. However, one could say the Cosmists had a more ambitious goal: rather than merely the classless society of the Bolshevik future, the Cosmists wanted to conquer death itself and master the entire universe.

As Richard Stites has pointed out in his book Revolutionary Dreams, the post-Revolutionary period in the USSR was one of great social experimentation and utopian imagination. Stites noted that despite Fedorov’s Tsarist and Orthodox Christian roots, his influence extended to various actors taking part in the revolution.4 The Cosmist followers of Fedorov found themselves in contact with the infamous Proletkult, a mass organization based on the ideas of Bogdanov that aimedto construct a new proletarian culture that would transcend the culture of bourgeois society. Proletkult was where the pre-revolutionary followers of Fedorov, Tsiolkovsky in particular, directly connected with Bolsheviks in their quest to build a new society. Yet Proletkult would be derided by both Lenin and Trotsky. Trotsky critiqued it for trying to build a new proletarian culture without first bringing the best of bourgeois culture to the illiterate masses, arguing that the new culture of socialism would be an expression of universal humanity rather than a specific class. In 1920 Proletkult was integrated into the Narkompros or Ministry of Education, no longer continuing an independent role but bringing many of its ideas into the Narkompros itself.

After the end of the Russian Civil War and the beginning of the New Economic Policy (which ended the state of economic war on the peasantry by tolerating a level of agrarian commodity exchange), a period of stability emerged. This period of stability was one of great artistic and scientific experimentation, where the “cosmic imagination” of the Russian Revolution was at its most visible. The scientific and artistic pluralism of the NEP meant the works of the Russian Cosmists flourished, with Tsiolkovsky doing some of his most creative work.

The ideas of space travel gripped much of the Soviet masses, with Cosmonautics societies popping up around the country simply to discuss its possibilities. One such society was the Obshchestva Izucheniia Mezhplanetnykh Soobshchenii (Society for the Study of Interplanetary Communication), which organized a lecture in 1924 by the engineer Mikhail Lapirov-Skoblo which was so highly anticipated it sold out two days early. This same year the film Aelita: Queen of Mars, where a young man travels to Mars to unite with Queen Aelita to overthrow the “Martian Bourgeoisie”, was released. In the period from 1921 to 1932, Russian media published nearly 250 articles and more than 30 nonfiction books about spaceflight, dwarfing the mere two nonfiction works published in the United States. A discourse of utopian imagination and belief in the power of science were opened up to all. This was not through top-down state commands, but the experience of a society itself living through the actual process of trying to build a new world. In fact, the Soviet State, preoccupied with political challenges, did very little to promote such thinking. And yet this lack of interest from the Soviet state did not prevent a massive cultural interest in space exploration; the general ethos of the revolution was a catalyst all on its own. Anything seemed possible, and space travel was not an unreasonable goal. Many believed that the forces unleashed by the revolution could make the dreams of Fedorov and Tsiolkovsky into a reality.

The ideas of the Cosmists show the level of both crankery and ingenuity produced by the NEP culture at the time. While the Cosmists were not the only space enthusiasts during this era, they are most easily available to study in their own words. The works of Cosmists aimed to be both scientific and prophetic, combining mysticism and science in a way one only finds in science fiction. The Cosmists aimed to go beyond storytelling and instead provide a vision for the future, one that was to be created in the Workers-Peasants Republic of Soviets. To best grasp the general vision of the Cosmists, we shall look at the work of Tsiolkovsky in the 1920s, when his ideas were at their height of influence among various cliques of space enthusiasts.

After the revolution, Tsiolkovsky continued his work outside the Bolsheviks party but remained respected by figures such as Lenin. While not a Bolshevik, Tsiolkovsky found that the October Revolution had ushered in a culture in which his ideas could flourish and become influential. Despite this, state funding did not come easily, possibly because his ideas ultimately seemed too absurd to warrant serious state funding in a time of economic difficulty. It wouldn’t be until the 1930s when Tsiolkovsky was granted state recognition for his work and was awarded the Honor of the Red Labor Banner, being invoked as a homegrown scientific hero who didn’t follow the sensibilities of bourgeois specialists who were under attack at the time.

In his work The Earth and Future of Mankind, Tsiolkovsky begins by speculating that at least 500,000 Earth-style inhabitable planets exist in the universe and that it would be possible to pierce through the atmosphere and “blaze a path into the Ether, the interplanetary environment, and beyond.” Even beyond this, “man would build homes in the Ether….encircle the sun, and people’s wealth would increase billions at a time.” One can see in this description a vision of what some have called “space communism”, which certainly inspired later visions of many Soviet artists in the period of the “Space Race”. Despite his calls for expanding society beyond Earth, Tsiolkovsky still sees Earth as humanity’s primary base and notes that leaving its domain is no reason to forget the need to “clean it up of its torments”. Echoing his religious tendencies, Tsiolkovsky claims that the destiny of the Earth is the destiny of the universe. Earth is a sort of perfect ideal, one of all other planets to live up to.

Tsiolkovsky’s prometheanism leads him to see an earth that is unused, full of soil that awaits transformation. His solution is for all of humanity to unite, end private ownership of property, and wage a “struggle on nature” to cultivate unused land and eradicate hostile elements. These schemes may sound rather bizarre today but are related to the struggle to modernize agriculture, which at this time was limited to small plots owned by peasants. Further, Tsiolkovsky speculates how all corners of the Earth could be made habitable for humans using scientific methods, combining a sort of messianic desire to expand the dominion of man with faith in science to placate the miseries of nature. “Man shall slowly overcome everything,” Tsiolkovsky would write.5

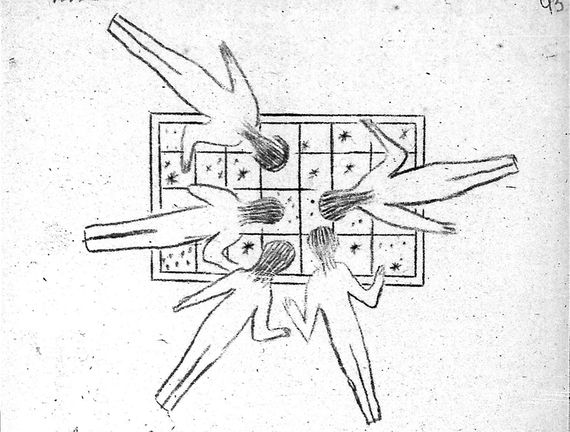

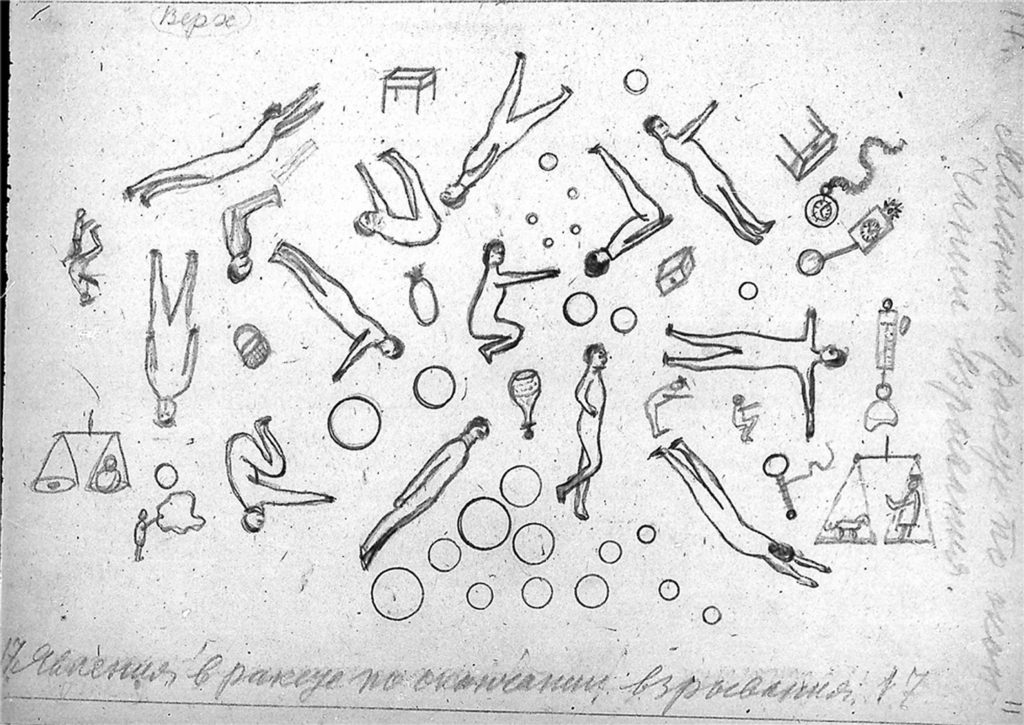

The prometheanism of Tsiolkovsky goes as far to suggest what looks like geo-engineering, saying that deserts must “become a paradise on Earth” and be “covered with special inhabitable greenhouses.” The aim is to make the deserts immensely agriculturally productive, further allowing human flourishing on Earth. Tsiolkovsky also calls for the use of what today can only be called solar panels. This grand transformation of nature, of “filling Earth’s entire surface to the extreme” is merely a part of a grander process of mankind conquering the Cosmos, as he adds that artificial moons containing industry will already exist before this task is completed. This conquering of nature on Earth is merely a prelude to the conquering of the solar system, which he adds would hold a population of no fewer than a thousand trillion.6 In fact, the aim of Tsiolkovsky’s agenda in The Future of Earth and Mankind seems to be to allow the maximum expansion of a human population, which to him inevitably leads to greater perfection of the individual and a “more advanced solar system.”7 His end result is essentially to make Earth the equivalent of a capital city in a broad solar system. Tsiolkovsky’s vision of massively terraforming of the Earth may sound absolutely horrendous in an age of life-threatening climate change. Yet one cannot one help but appreciate his ambitions, a sort of techno-utopian drive that goes beyond what the Bolsheviks themselves dreamed of at the time.

Tsiolkovsky was also fascinated by the prospects of intelligent life, some he hints at in The Earth and the Future of Mankind with his mention that 500,000 Earth-like planets exist. His own personal philosophy of panpsychism and monism were based on the idea that all matter is composed of living things, down to the last atom. This meant that the needs for life were the same on all planets, from there arguing that it is possible for planets to have intelligent life. Using what can only be described as an early form of the Drake Equation, Tsiolkovsky then argued that if intelligent life were to develop life on other planets than the development of space travel for these beings would be inevitable just as it was for humans. Objections to this argument that Extraterrestrials would already have visited us or would have made their presence known are also addressed in Tsiolkvosky’s work, claiming that it may take years for such an encounter or that other species are too engaged with visiting more advanced species.8

Panpsychism as a general theory of the universe would guide all of Tsiolkovsky’s work. In his 1925 exegesis on the topic, Panpsychism, or Everything Feels, Tsiolkovsky aims to give a simple rundown of his philosophy. He promises “conclusions more comforting than the promises made by the most life-affirming religion” while also adding that “compared to me, Spinoza is a mystic.” Written after the Bolshevik revolution while possibly trying to win favor with the new revolutionary regime, it is quite possible Tsiolkovsky is aiming to hide his religious sensibilities if not leaving them behind entirely. Instead, the universe is teeming with life, all organisms feeling pain or pleasure thus having the property of sensitivity. Sensitivity, or responsive, is not equal for all organisms however; plants have less sensitivity as do dead bodies. Therefore all of the universe is one substance, but with differing degrees of sensitivity. This is the essence of panpsychism, further arguing that all matter in the universe essentially follows the same laws. From this, Tsiolkovsky argues that the tendencies that led to life on Earth will lead to life on other planets.9 This is the basis for his aforementioned argument that extraterrestrial intelligence must exist. His panpsychism is also a basis for a unified human community around a rational society, which like his vision of terraforming the Earth is a launching ground for colonizing not merely the solar system but the entire Milky Way. What is interesting here is how a logical line is drawn from the conclusions of pansychist philosophy to the domination of the universe by mankind, a sort of need to realize the inherent connection of all matter and the dissemination and achieve perfection in the Cosmos.

Another Cosmist who made explicit the link between immortality and space travel was Alexander Svyatogor, an anarchist futurist poet who like many anarchists collaborated with the Bolsheviks. During the Russian Revolution, Svyatogor expropriated bourgeois apartments alongside the anarchist Black Guards, then going to Ukraine to fight the German and Austrian occupiers. Back in Moscow, Svyatogor would break from his previous organization the Anarchist Universalists and form a group of Biocosmists-Immortalists who operated under a slogan of “immortalism and interplanetarism”. His work Biocosmist Poetics from 1921 begins with a claim that natural laws are merely expressions of a particular balance of power, a balance that can be interrupted with the introduction of a new force or removal of an existing one. Thus it is possible to set the forces of immortality into motion. A similar attitude is taken to space travel by Svyatogor:

“Our agenda includes “victory over space.” Let us not refer to it as aeronautics – it is not enough – but rather space travel. Our Earth must become a spaceship steered by the wise will of the Biocosmist. It is a horrifying fact that from time immemorial the Earth has orbited the sun, like a goat tethered to its shepherd. It’s time for us to instruct the Earth to take another course. In fact, it is also time to intervene in the course taken by other planets too. We should not remain mere spectators, but must play an active role in the life of the cosmos!”10

One cannot help but be reminded of Trotsky’s dictum in Their Morals and Ours that “the means are justified only if the ends are” and that the ends are justified if they lead to “increasing the power of man over nature and to the abolition of the power of man over man.”11 Arguably the Cosmists took this to the extreme, believing that man’s power over nature would extend to the point where death was no longer a necessity. This was a vision of socialism that aimed to challenge everything that seemed fixed, even natural laws of science, believing that humanity taking control over its own conditions could change the very mechanics of the universe. Svyatogor sees the revolution not merely ushering a new mode of production, but exiting “all previous history, from the emergence of organic life on Earth to the massive upheavals of the past few years, constitutes one age: the age of death and petty deeds.” The new era for the Biocosmist is the age of “immortality and infinity”.12

Other Cosmist thinkers would also straddle the line between occultism and science. Leonid Vasil’ev was a parapsychologist who experimented with telepathy, claiming to have found proof of such phenomena in his experiments. One can see the influence of the aforementioned panpsychism of Tsiolkovsky, where all life is interconnected with living energy. If immortality is possible, why not telepathy? Chizhevskii, a friend of Vasil’ev, would develop a theory that comes off as a mix of pseudo-scientific astronomy and Spengler, where there are four cycles of world history based on the activity of the sun: the epoch of minimal excitability, the epoch of mounting excitability, the epoch of maximal excitability, and the the epoch of diminishing excitability. Each phase has a corresponding level of mass political activity, where increasing excitability from transition to phases leads to social upheaval and then stability.13 While Tsiolkovsky was able to combine his flights of fancy with actual scientific work, Cosmists like Svyatogor, Chizhevsky, and Vasil’ev were closer to occultists than proper scientists.

The role of the utopian and mystical visions of the Cosmists was not so much to serve the Soviet state as it was a part of a broader artistic and scientific culture (with the Cosmists a strange synthesis of both art and science) that carried much pluralism. For Bolsheviks like Lunacharsky who set the tone of cultural affairs in the early Soviet Republic, such musings had value in developing a new socialist consciousness regardless of their instrumental utility to developing industry. Lunacharsky promoted artistic experimentation and only excluded outright reactionary provocations, while the sciences were not straight-jacketed by the state-imposed orthodoxy. Rather, early Bolshevism sought to win the most talented bourgeois scientists to the revolutionary project while promoting their work regardless of political affiliation.14 This pluralism combined with a general attitude that society was taking a leap into an unknown frontier where humanity would take control of its own destiny led to an explosion of new thought, much that is completely forgotten to this day. As one can see much of this thought was on the verge of pure crankery and quite laughable today. Yet perhaps crankery is a necessary product of a broad and innovative scientific and artistic culture and cranks perhaps have something useful to tell us despite their tendency to make entries into irrationalism. Reading Tsiolkovsky’s visions of terraforming the planet may seem absurd in an age facing global warming, but perhaps they demonstrate the kind of scale of action and transformative drive that conquering the threat of species extinction may require.

With the rise of Stalin, the “cultural revolution” that accompanied his industrialization and collectivization drives would see an introduction of rigidity into the arts and sciences. This meant that the Cosmists would eventually be marginalized, with the exception of Tsiolkovsky who nonetheless was controversial due to his belief in eugenics. Crankery still existed, such as the likes of Lysenko, yet only was tolerated because it fit the bounds of state ideology and the needs of an industrializing state. The utopian experiments of the 1920s were shut down for not conforming to the needs of mass industrialization, and socialist realism became official doctrine in the arts. Science became purely instrumental for the needs of industrial development and had to conform to the official Marxist-Leninist ideology. This process didn’t happen overnight and came to a height with the purges of the mid to late thirties. Yet it was clear that the atmosphere of experimentation that produced the Cosmists was long gone.

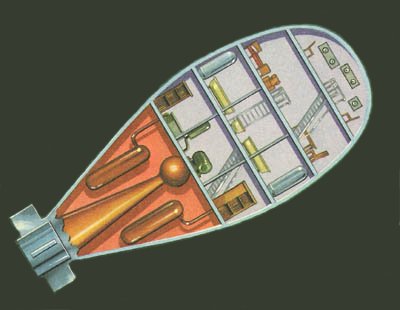

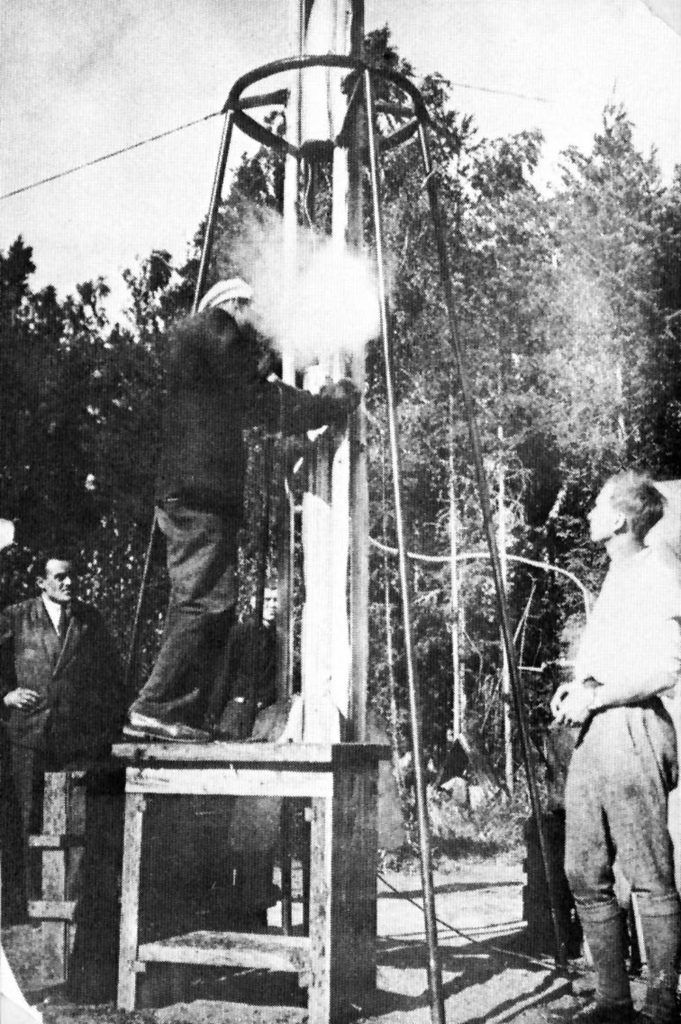

Yet ironically fascination with Space was picked up officially by the state, as rocket technology became an interest of the military. This was not without its links to the space enthusiast Cosmists of the 1920s. A key link was the figure of Fridrikh Tsander, member of the aforementioned Society for the Study of Interplanetary Communications who would quit his job in 1927 to live off donations of his comrades and design a space plane.15 Tsander was very much like Tsiolkovsky in that he was prone to utopian flights of fancy while having a practical mastery over science and engineering. In 1930, independent from the state, Tsander was testing what was essentially a primitive jet propulsion engine, built from a modified blowtorch, a spark plug for ignition, gauge to adjust fuel level and conic nozzle for exhaust. After a long series of rejections, Tsander eventually joined the Osoaviakhim, or Union of Societies of Assistance to Defence and Aviation-Chemical Construction of the USSR. Within the Osoaviakhim Tsander formed the GIRD or Group for the Study of Reactive Motion. It was here where Tasander met Korolev, an aeronautics enthusiast who would go on to become a hero of rocket science and the Soviet front in the Space Race. The GIRD was funded entirely by volunteer donations at one point, but in 1933 this would change. Marshal Tukhachevskii took interest in the research and development of rockets, and military research and development would now include rocketry.16 While the utopian goal of space travel was put to the side, the technical aspirations of rocketry would expand and set the stage for the world-historic voyages of Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin.

There is a certain irony in how things played out; the rise of Stalinism saw the explosion of cosmic imagination repressed in favor of monolithic party ideology, yet the industrialization of the country and massive expansion of the military also allowed the development of rocket technology they once only dreamed of. Illustrative of this contradiction was that Korolev would design the basis for the rocket that would take Sputnik into orbit while in the gulag. Yet Korolev was required the keep his desires for space travel a secret during his research on military technology once released from the gulag, and it wasn’t until 1956 that he would convince Khrushchev to take up the production of satellite technology, particularly as a propaganda win against the USA. With this, the proponents of space travel were able to meet the needs of the Soviet state and a new era of space travel began. While the Cosmists’ dreams of immortality and telepathy remain unrealized, their goals of using rocket propulsion to leave the Earth became a reality.

- Siddigi. Asif A. The Red Rockets Glare, 115.

- Siddigi. Asif A., 25.

- Fedorov, Astronomy and Architecture, Published in Russian Cosmism ed, Boris Groys, pg 58.

- Stites, Richard, Revolutionary Dreams, 171.

- Tsiolkovsky, The Future of Mankind, Published in Russian Cosmism ed, Boris Groys, pg 114-119.

- Ibid, 128-129.

- Ibid, 130.

- Lytkin, V., Finney, B., & Alepko, L.,Tsiolkovsky – Russian Cosmism and Extraterrestrial Intelligence, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 36, NO. 4/DEC, P. 369, 1995

- Tsiolkovsky, Panpsychism, or Everything Feels, Published in Russian Cosmism ed, Boris Groys, pg 143.

- Svyatogor, Biocosmist Poetics, Published in Russian Cosmism ed, Boris Groys, pg 83.

- Trotsky, Their Morals and Ours, 1938.

- Svyatogor, 84.

- Chizhevsky, World Historical Cycles, Published in Russian Cosmism ed, Boris Groys. Pg 18.

- Helena Sheehan, Marxism and the Philosophy of Science, pg 156.

- Siddiqi, Imagining the Cosmos, 116.

- Ibid, 152-153.