The 1970s were a time of turmoil and transition. Connor Harney gives a Marxist account of this pivotal decade.

Nostalgia for the Past

As we enter a new decade that will inevitably wear the birthmarks of the last, it seems of utmost importance to reflect on the current trajectory of the left in the United States. There are many reasons to both lament the state of the left in the U.S. and to remain hopeful of its potential. While it is uncertain if the current popularity of socialism, the upswing in labor militancy across 2018 and 2019, and Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential run will provide a foundation for a lasting movement that will outlast the current electoral cycle, the seeds do seem to be there. At the same time, it is not enough to expect them to sprout on their own. The seeds of the emergent socialist movement must be tended to, and must be provided an environment where they can flourish. For us, this means that we must not limit our study to the fertile grounds of revolutionary history. It is not enough to just survey 1789, 1871, 1917, 1959, or 1968, and imagine that it is only those moments that can help plot the path forward.

First of all, this approach often leads to a politically determined position that ignores the economic conditions of those moments, and second, it assumes that revolution is just around the corner—an understandably optimistic assumption that in the long term douses the flames of youthful militancy and burns out even the most committed. Even so, it is still wrong to outright dismiss the revolutionary potential of the moment the way that many on the social-democratic left often do. Socialists, communists, and others on the radical left should be at the same time prepared for both immediate insurrection and the slow process of movement building: be it by preparing the ground for a new working-class party or by rebuilding and forging new trade unions and other organizations of proletarian solidarity. In doing so, we can ensure that Santiago and Paris are not just burned to the ground over a repressed discontent with the status quo.

Our frustration should be channeled towards rebuilding these cities in our own image out of the ashes. Many within the embryonic socialist left, especially within the “democratic socialists”, but also among the purportedly more radical trends like Marxist-Leninists or Trotskyists look to the period of the 1930s and 1940s to draw inspiration from. In particular, they look at the New Deal and welfare states constructed contemporaneously in Europe, and arguably the Soviet bloc as well, and focus on the social leveling and the higher standard of living for working people as an aspiration in a time of absurd levels of wealth inequality. The sentiment seems to be “if it worked then, it can work now.” But good Marxists should always be uneasy applying the traditions of the past whole cloth to the present. As Marx famously quipped in the Eighteenth Brumaire, “men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.”1

The specific conditions that allowed radicals to push for reforms to the capitalist order are entirely different from those present at the current moment. When the pieces of legislation that made up the New Deal were passed, the left was at the peak of its strength and was acting in the context of a worldwide depression that grounded capitalist economies to a halt—alongside the memory of the October Revolution which still haunted the minds of the ruling class like a waking nightmare. Casting aside the question of whether a Green New Deal or Medicare for All is possible under current conditions, we should ask instead whether or not such reforms are enough? The answer to such a question is to be found not in the period of the New Deal or Great Society programs, but in the crises of the 1970s that created and forged the current moment. It was at this moment that the limits of those reforms were made clear. Not only was the dilemma of stagflation unthinkable from the standpoint of Keynesian orthodoxy, the doctrine’s salve no longer healed the wounds of the U.S. economy.

In order to grapple with that period, we need to complicate the well-tread intellectual history of Hayek and Friedman that is so often trotted out in order to explain the rise of neoliberalism. As the story usually goes, by the 1980s, the conservative movement had succeeded in its long war to erode the social peace that made up the postwar consensus, and in the subsequent turmoil managed to implement its agenda of privatization and tax cuts proposed by Friedmanites. While part of this may be true, it is not the whole story. To this idealist conception of historical development, E.J. Hobsbawm once wrote that historians should remember that ideas “cannot for more than a moment be separated from the ways in which men get their living and their material environment [… because …] their relations with one another are expressed and formulated in language which implies concepts as soon as they open their mouths.”2

Rather than assume that neoclassical economics created the current moment, the more important line of inquiry should be as follows: how did the crisis of the postwar pact between capital and labor and the Keynesian consensus produce the conditions that allowed previously marginal ideas to become hegemonic not only at the commanding heights of the economy, but even among the working class themselves? Written in May of this year for the Correspondent, Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s article “The neoliberal era is ending. What comes next?” perfectly encapsulates such a view of the past. He correctly diagnoses the cracks in the facade of neoliberalism but does so starting from a faulty premise. Bregman takes the architects of neoliberal economic thinking at their own word, without accounting for the process by which their thinking went from marginal to common sense. He cites Milton Friedman’s view that in times of crisis, “ideas that are lying around” are picked up if the “proper groundwork” has “been laid.”3 But what groundwork? And why is it that certain ideas are picked up over others? Bregman claims that over the course of the crises of the 1970s “spread from think tanks to journalists and from journalists to politicians, infecting people like a virus.”4 He does not try to explain the crises, nor address why the old Keynesian medicine could not cure its patient any longer, but in his description of how neoliberal ideas became hegemonic we find our answer. For him, in society there is a battle of ideas over who can best explain the world, and to the victors goes the spoils of the material world, that is until their ideas no longer make sense. But hidden in his word is the class explanation for the ideas that get picked up. Think tanks, journalists, and politicians do not by and large represent the working class, particularly in the United States where there has never even been a labor party. Instead, the contest of ideas described here is largely between elements of the ruling class in an attempt to consolidate its own position in a time of crisis.

Later in the piece, Bregman begins to wonder who will be the progenitors of the new economic ideology, suggesting the names of Thomas Piketty, Emanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman, or Marian Mazzucato. What these thinkers have in common is a desire to return to higher tax rates and more government regulation, believing that those policies could reverse high levels of income inequality and restore economic growth by putting more in the pockets of everyday people. Piketty is an interesting choice, as his first book Capital in the 21st Century was a lightning rod of admiration and controversy when it was released. In it he documents the trend toward higher inequality since the 1970s, offering politics as the solution to the problems of the economy. His latest book, Capital and Ideology is an attempt to bridge the gap between his prescriptions and how they might be practically realized.

In a review of Capital and Ideology, liberal commentator and economist Paul Krugman claims the book can be described as “turning Marx on his head.”5 According to Krugman:

In Marxian dogma, a society’s class structure is determined by underlying, impersonal forces, technology and the modes of production that technology dictates. Piketty, however, sees inequality as a social phenomenon, driven by human institutions. Institutional change, in turn, reflects the ideology that dominates society: ‘Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.’6

For Piketty, the dominant ideology of a given time is created by ‘ruptures’ that can be used as “switch points” by a “few people” to “cause a lasting change in society’s trajectory.”7 A few people? Piketty himself perhaps? What Krugman misses in his explanation of Marxian orthodoxy, is that the relationship of the forces of production to society is not a one to one reflection. In fact, technology itself is shaped by the relations of production, which include within them the ideology necessary to reproduce society as is, and in the case of capitalism, its continued expansion. By turning Marx on his head in this way, we do not even get Hegel, who in his own way had a materialist conception of history. Instead, we get a view of a society unmoored from its material basis, one in which politics is merely a discursive exercise in figuring out the best way to do things, the cream of the intellectual crop will float to the top.

To go back to Bregman, his theory of change very much aligns with that of Piketty: someone thinks of an idea and it gets put into practice. He claims “that the way we conceive of activism tends to forget the fact that we all need different roles.”8 Instead, he believes some tend to focus on the work of grassroots mobilization, others on that of high-profile leaders, while still others struggle over whether to protest or begin “the long march through the institutions.” Bregman argues that we must remember that this is not “how change works.” “All of these people,” from Occupy protesters to “lobbyists who set out for Davos,” have their roles.9 The message seems to be that only if people remember their place, then our society could see progress. Leave it to the Pikettys and the Krugmans of the world to figure out the problems of the world, to bring the stone tablet solutions down from the mount, but it is for those in the street to spread the good word. From this conception, the question remains: After the long line of world-historic crises faced in only the first two decades of the 21st century, why do people reject the sermons of our new economic high priests? Partly, I think this can be attributed to people’s rightful perception that these thinkers themselves offer no real plan to deal with the present. Their role is to project the programs of the past to our current circumstances without dealing with the failings of the New Deal project in the first place: a shortcut for young people desperate to attend to the alienation of their own lives and the imminent climate crisis facing the planet.

From this inability or unwillingness to deal with the flaws in their own conceptions of the New Deal horizon we arrive at two faulty assumptions. Firstly, that if left unhindered by the machinations of the Right, those working today, the children and grandchildren of the greatest generation, would find themselves working the “three-hour shifts” or the “fifteen-hour work week” that Keynes famously predicted.10 Flowing from the first comes the second assumption: namely that the economic crises of the 1970s were entirely political in nature, be it the consequence of oil shocks or the lack of political will necessary to take the steps required toward full employment. The secret to the peaceful transition from capitalism had already been cracked—it was only a matter of putting in the right people to implement it. Setting aside the logical problem of a political strategy that requires no opposition to realize, both of these presuppositions fail to deal with the real political-economic problems of the Fordist era. From the widespread discontentment and alienation of a consumer society still predicated on the production of value and the increasing inability of the capitalist basis of society to cash the check of promised affluence for all those who toil.

Nostalgia of the Past

It was not only those living at the time that were unable to resolve these contradictions inherent to the postwar consensus. Even now, there are those who continue to either outright ignore the problems inherent to that political-economic arrangement. They do so, by either refusing to see that economic order as a problem at all, or at best, they are ignorant of its history. By doing so, they help to maintain the marginal position of the left by sustaining an unfounded nostalgia over a progressive program.

This longing for a bygone era of increased possibility for a segment of the working class is not new to the twentieth-first century. It began as soon as the cracks in the old order were beginning to have ramifications in the daily lives of working people. It is no wonder then, that in the last few years Christopher Lasch has seen a resurgence in currency among some circles within the radical left. Lasch was a witness to the unraveling of social solidarity and the rise of a “culture of narcissism,” and understandably lamented the “logic of individualism” carried to “to the extreme of all against all,” in which “the pursuit of happiness” became “the dead-end of narcissistic preoccupation with the self.”11 As a historian and preeminent critic of society, he identified atomization as the ill that ailed Americans as the turbulent 1970s drew to close. This diagnosis brought Lasch to discover the solipsistic self-awareness that informed the condition of postmodernity. He writes in the Culture of Narcissism:

Distancing soon becomes a routine in its own right. Awareness commenting on awareness creates an escalating cycle of self-consciousness that inhibits spontaneity. It intensifies the feeling of inauthenticity that rises in the first place out of resentment against the meaningless roles prescribed by modern industry. Self-created roles become as constraining as the social roles from which they are meant to provide ironic detachment.12

Yet, his critique of this form of disassociation offers no way out of the endless spiral of the self he describes. Instead, what little solace Lasch does offer was a romanization of the past that ultimately led him to the dead end of fetishizing the patriarchal family.13

Still, Lasch’s description of a society in decay is not without value for the left. Indeed, even his intuition that the history could offer a sense of hope for the future can be salvaged sans the rose-colored and romantic relationship to the past, for “a denial of the past, superficially progressive and optimistic, proves on closer analysis to embody the despair of a society that cannot face the future.”14 Andreas Killen, a historian obviously influenced by a Lasch’s unique brand of history infused with both a sociological and psychological analysis, has more recently characterized 1973 as a collective “nervous breakdown” from which the United States never recovered. Echoing the concern of forgetting the past, Killen writes that the inability to grapple with the malaise that infected the American psyche after the failure of 1968 exists even to the present.

In a certain sense, he is correct. The revolution that the New Left envisioned never came to fruition, and without the power to transform the material basis of society in the United States, the concern became the realm of culture.15 Yet, what this analysis misses, is that the revolutionary moment was not simply reacting to the remaining vestiges of de jure racism and sexism. As the 1960s progressed it became clear that it was necessary to not only dismantle the juridical apparatus of oppression but also to remove the levers of exploitation that the capitalist left firmly engaged. What many did not foresee, however, was the drying up of the material conditions that had made mass politics possible in the first place.

This inability to understand the contours of a changing political-economic constitution of late capitalism underpinned not just their moment, but also the current one. Killen contends, “the crises of the 1970s are not so easily buried; indeed they have emerged with new intensity in our time.”16 The historiography of the 1970s has grown immensely since Killen penned 1973 Nervous Breakdown in the first decade of the new millennium, and within the wider historiography of the United States the decade has gone from marginal to what Judith Stein called a “pivotal decade.” This essay seeks to flesh out a historical materialist analysis of the 1970s in order to add to the ongoing debate over the political-economic trajectory of the second half of the twentieth century, not to provide a roadmap to a socialism, but rather to point out the assumptions that led to the political cul-de-sacs informing left debates for more than half of a century—be it through imagining a return to the politics of the New Deal, or for the more radical left, a return to the Popular Front of the 1930s.

Past the Post-Industrial Society

The historian Jefferson Cowie, has argued for years that the New Deal was “the Great Exception” to the American national project. While there are components of his arguments that may be overstated, there is a truth to the overall content of his message. These thirty golden years of American capitalism may have stoked a small, but long-standing spirit of egalitarianism in the United States. At the same time, it is ultimately a footnote in the larger national project, and yet, so much of the popular image of the country emerged from this moment. Even the political and cultural norms we observe now were shaped by this aberrational moment. Indeed, part of the inability with those living through the breakdown of New Deal order was the assumption that the good times were here to stay, that the pact between labor and capital would last forever, and that the perceived mutually-beneficial relationship would continue to produce mutual gains for all.

In his introduction to Labor in the Twentieth Century, former labor secretary for the Ford administration and labor economist John T. Dunlop called the twentieth century “the worker’s century.” His misplaced but understandable optimism was part of the ideological fog that shrouded the postwar compact’s breakdown. Written in 1978, as the seams were really beginning to unravel around Keynesian orthodoxy, he could still say that any “reader of this volume must conclude that the twentieth century is likely to be known as the century of the worker or of the employee in advanced democratic societies,” and further that, “the first three-quarters of the century provide a desirable frame of reference to consider the course of development out to the year 2000.”17

While Dunlop and Galenson’s volume is billed as a comparative work, looking at the trajectories of a handful of advanced industrial economies, more often than not it falls prey to an analysis of Keynesianism in one country. That is, it bases itself on the assumption that redistributive welfare state and regulatory apparatus can rely on the industry of its own country to provide the material basis for those policies to operate. Only four years later, another set of labor economists wrote in their predictions for the future of the field that:

it is likely that the current awareness of the effects of world-wide competition, the interdependence of national economies, and the popularized comparisons of differences in national systems of industrials and management process will further spur in comparative and international industrial relations research.18

Clearly, the encroachment of the global on the national became something that could not be ignored even by those invested in maintaining the conventions of the old order. Or, to put in Marxist terms, if national economies are like giant cartels, they must compete with one another due to the coercive laws of competition, which in the long term to push them to increase the productivity of labor through either investment in more advanced techniques of production or the increased level of exploitation of labor through suppressing wages or increasing the working day. Such an impulse could not be contained as the United States’ global dominance eroded: a result of a shrinking advantage in productive capacity, which also underpinned its ability to maintain a stable international credit system.

Part of this is what historian Judith Stein argues in her seminal work Pivotal Decade. Where she diverges from a certain Marxist reading of events is clear from her book’s subtitle: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies. For Stein, the political class’ inability to protect manufacturing in the United States was the downfall of America’s detour into social democracy. In her view, these jobs were not just any jobs, but productive labor that allowed a large portion of the working population to live “the good life.” The book’s final chapter deals with the current “age of inequality” born out of this failure to maintain the economic hegemony of the United States. In it she prescribes a revival of manufacturing. According to Stein, “as long Americans use computers, wear clothes, drive autos, build with steel, play video games—in short, do everything,” there will be a need for someone to do the work, and for that reason, the explosion of debt-fueled consumption in the years following the crisis of the 1970s reflect a society in which “Americans consumed these items but did not make enough of them.”19

What Stein overlooks, is that manufacturing was not simply outsourced, it was also automated. Fewer workers are required to oversee the production of the coats, chairs, cars, and computers that are a part of daily life in the modern world. At the same time, her view also reduces hundreds of millions of people in the world to merely unproductive vagabonds leeching off the work of those doing those “making things.”

Setting aside the first point of automation, the question of productive labor within the world economy is an important one. In the often ignored second volume of Capital, Marx discusses the importance of the work that goes into both maintaining and transporting commodities, which, if nothing else, is the work of the grocery clerk, the long-haul trucker, the fast-food worker, and the Amazon warehouse worker. He writes:

Within every production process, the change of location of the object of labor and the means of labor and labor-power needed for this plays a major role; for instance, cotton that is moved from the carding shop into the spinning shed, coal lifted from the pit to the surface. The transfer of the finished product as a finished commodity from one separate place of production to another a certain distance away shows the same phenomenon, only on a larger scale. The transport of products from one place of production to another is followed by that of the finished products from the sphere of production to the sphere of consumption. The product is ready for consumption only when it has completed this movement.20

In other words, for the modern consumer to enjoy their Big Mac, watch Netflix, or read the newest novel by their favorite, labor is required to not only produce goods but to transport and maintain them. Crucial to this circulation of commodities across the country, and more broadly the globe, is physical infrastructure like roads, cellphone towers, and electrical lines—all of which are run or maintained by any army of workers who ensure their continuous movement. In concrete terms, as important as the papermill, the slaughterhouse, and the factory, are the warehouse, the freight companies, and the restaurant. While there may be a kernel of truth to Stein’s argument about a decline in productive work, what Stein’s work shows more than anything else is the limits to a strictly national labor movement and the attempt to reform capitalism within the borders of one country. The highly-centralized business unions within AFL-CIO proved outmoded against increasingly decentralized and international corporations. In a word, interdependence carried the day, and the old ways of organizing proved incapable of withstanding its onslaught.21

On the other side, there are many that have cheered on the decline in manufacturing in the United States, extolling the virtues of the so-called post-industrial society—a term popularized by sociologist Daniel Bell in his work The Coming of the Post-Industrial Society published in 1974. In the same year, Harry Braverman, metalworker and long-time editor of Monthly Review Press challenged this vision of the future, claiming in his agitational magnum-opus Labor and Monopoly Capital that such a view represented another in long line of “economic theories which assigned the most productive role to the particular form of labor that was most important or growing most rapidly at the time,” but in the last analysis, he suggests, each form of labor peacefully coexists “as recorded in balance sheets” of multinational corporations.22 Most importantly, rather than a decline in the application of Taylorism to the world of work, the rise of the service economy represented its universalization. As a truck team member at a major grocery chain, his description of “a revolution…now being prepared which will make of retail workers, by and large, something closer to factory operatives than anyone had every imagined possible,” is no longer one possible path of the historical development of the forces and relations of production, but rather a foregone conclusion, at least in that segment of the service economy.23

Braverman’s unique conception of deskilling flows from this notion of scientific management’s universal application. With the proliferation of white-collars jobs over blue-collar jobs in manufacturing, there is often the assumption that increased requirements of education and the more technology is applied to accomplish workers’ daily tasks on the job the more skilled the overall workforce, but what Braverman contends is:

The more science is incorporated into the labor process, the less the worker understands of the process; the more sophisticated an intellectual product the machine becomes, the less control and comprehensions of the machine the worker has. In other words, the more the worker needs to know in order to remain a human being at work, the less does he or she know.24

For example, ask someone whose job it is to stock the shelves at the local grocery store how what they are stocking gets to the store and how the store knows to order it, chances are the response will be a blank stare—not due to any lack of intelligence on the part of the worker—but rather, because of the complexity of daily life under the modern division of labor mediated by network technology.

Such a state of affairs cannot help but help alienate the working class from one another. Not only do they become a cog in the giant machine of global capital, but they also can no longer imagine how their own movement has an effect on the other gears. While Braverman rightfully dismissed the sociologists and other academics whose sole focus was studying this alienation over the objective conditions of work experienced by workers over the course of their careers, their scholarship can help highlight how those conditions are then experienced on a psychological level.

After years of successive strike waves, culminating in 1971 as the most active year for the labor movement since the militant heyday of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, the Nixon administration commissioned a Special Task Force to create a report on “work in America” for then Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Elliot Richardson.25 From the report, the administration would catch a glimpse into the lives of working people in order to get them back to work, or so they thought. Unfortunately for them, the results pointed to no easy answer, or at least to none within the framework of the postwar compact. The only solutions gestured either out of capitalism or towards the past, before the 1935 passage of the Wagner Act, which laid the ground for both a new kind of labor struggle and eventually paved the way for a labor truce. The report analyzes the problems of the “blue-collar blues,” “white-collar woes,” and the conflicts brought on by the increasing diversification of the workforce. According to the report, the blue-collar blues was not simply tied to traditional bread and butter issues like wages and benefits, but also to “[workers’] self-respect, a chance to perform well in his work, a chance for personal achievement and growth in competence, and a chance to contribute something personal and unique to his work.”26 This sort of alienation was not limited to blue-collar workers, but also was there for white-collar workers:

The office today, where work is segmented and authoritarian, is often a factory. For a growing number of jobs, there is little to distinguish them but the color of the worker’s collar: computer keypunch operations and typing pools share much in common with the automobile assembly-line.27

Clearly, the unraveling of the New Deal was not simply a question of “diminishing expectations” in the face of economic decline, but its terms became increasingly untenable from the physical and psychological toll wrought by the spread of scientific management to each sector of the American economy.

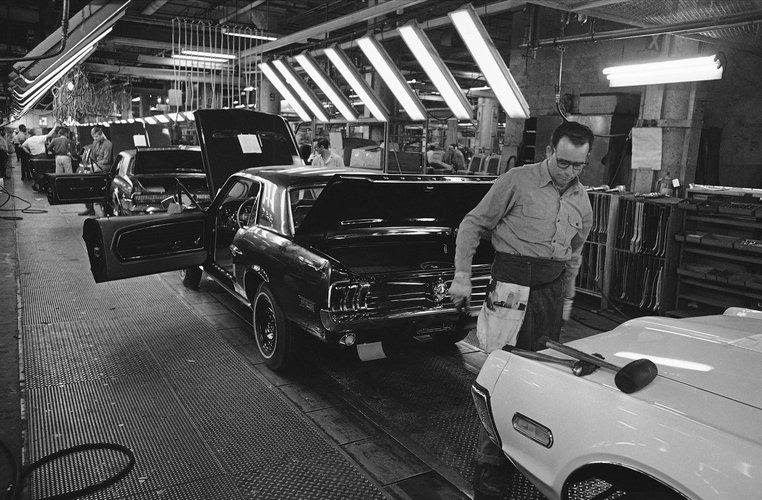

Bruce Springsteen captures this disillusionment with the old promise of the American dream in his song “Factory” from his 1978 album Darkness on the Edge of Town. In it, he describes the Faustian bargain faced by American workers as he sees his “daddy walking through the factory gates in the rain,” that “factory takes his hearing, factory gives him life.” To emphasize the truly one-sided nature of the deal, Springsteen sings that at the “end of the day, factory whistle cries/men walk through these gates with death in their eyes.”28 Like many working-class baby boomers, Springsteen had seen the way that the wear and tear of a lifetime of monotonous toil could wrack working people with an overwhelming sense of emptiness alongside the physical debilitation that often comes with manual labor. As the 1970s progressed into the 1980s, material decline faced by workers created a new reason for anxiety. In spite of this harrowing reality, it is important to highlight the problem of romanticizing the affluent society that came before our own neoliberal moment. Despite less precarity, there was still powerlessness felt in the face of the growing power of faceless multinationals to structure the daily lives of millions of people both in the workplace and the marketplace.

The Planning System and Monopoly Capitalism

This process by which the world became one colossal factory and market was experienced as deindustrialization in many advanced industrial economies. As the massive skyscrapers, factories, hospitals, schools, bridges, and feats of engineering, built by the hands of workers, decayed and fell into disrepair, there was little they could do. They may have made them, but they did not own them. To offer the words of Marx in the Grundrisse: “the condition that the monstrous objective power which social labor itself erected opposite itself as one of its moments belongs not to the worker, but…to capital.”29

Despite the monstrosity of a world increasingly alien to those who make their way in it, it should not be assumed that the great mass of people cannot overturn the existing order of things—that the monster cannot be slain. As the giants of the postwar era, like Ford, IBM, and General Electric began to dominate more and more aspects of everyday life, there came a tendency to view these monopoly monsters as invulnerable to the traditional foes of the individual firm within the capitalist system. Indicative of this perspective and informing much of the thinking on monopoly capital in the postwar was the work of economists like J.K. Galbraith, particularly in his work the New Industrial State first published in 1967. Here he attempts to illuminate the transformations of the capitalist system in the twentieth century, arguing that the conditions of free competition and exchange ceased to underpin the existing social relations within capitalism. Of course, from the standpoint of a critique of political economy, such relations never truly existed in the first place, except maybe in the utopian dreams of liberal partisans during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. As Marx wrote in the Manifesto, the bourgeoisie:

drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – Free Trade.30

They made a world in which “naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation” replaced an exploitation “veiled by religious and political illusions,” but at the same time, this very exploitation “accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals.”31 Utopian dream indeed, but only for those lucky enough to find themselves outside the ranks of the proletarians whose muscle and blood built this wondrous new world. Eventually, free competition and exchange became a watchword, part of a new veil forged to cover the nightmares created for the mass of society in realizing their bourgeois dreams. A new mystification for a new age.

Most important to understanding Galbraith’s contribution to political economy is an analysis of what he calls the “Planning System.” For him, the “Planning System” was a patchwork of the largest corporations in the U.S. economy, all working in concert to coordinate costs of production through a relationship to the state. In a certain way, Galbraith’s analysis aligns with conception of monopoly capital put forward by Marxists Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy in their work Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order, released only a year before the New Industrial State. If the tendency of global capitalism before World War II had been toward regular crises, then the postwar period can only be described as infinitely more stable. Both works attempted to explain this relative stability against the behavior of the capitalist system over the previous century and the beginning of the twentieth—behavior that helped bring about not only nearly thirty years of near-constant warfare—but also two world-historic revolutions which attempted to break with the very system that brought such destruction and misery into the world.

According to Galbraith, the “Planning System” arose out of the need to mitigate the uncertainty by ensuring continued profits alongside the rapid expansion of production. This growth was predicated on the application of increasingly complex technology. In turn, this meant a growing portion of a company’s capital had to be tied up in maintaining old and researching new technology. Part of this cost, as Baran and Sweezy also noted, was offset by state spending on both public research and government contracts, but ultimately, to ensure a return on these investments in technology, companies created massive advertising apparatuses that shaped the desires and wants of the consumer. Of course, such an operation could not be sustained without recourse to planning, and Galbraith believed that this forecasting replaced market mechanisms in determining what the cost of production and final price of commodities would be. While this “Planning System” may have stabilized capitalism to a degree, he worried that “we are becoming servants in thought and in action of the machine we have created to serve us.”32

On the one hand, Galbraith’s preoccupation with planning helped him see through the ideological mist of American society, where “the ban on the use of the word planning excluded reflection on the reality of planning.” However, his tendency to see planning as purely the necessary outgrowth of the size and level of technology of a particular firm tended to obscure the role of competition in determining the need for planning.33 While Galbraith acknowledged that technology was employed in order for firms to compete with one another—planning could, in the final analysis, eliminate a particular market altogether. This line of thinking brought him to two conclusions, the first that “size is the general servant of technology, not the special servant of profits,” and second, that “the enemy of the market is not ideology but the engineer.”34

The idea that the growth and complexity of capitalist society created an antimony between engineers and other technical experts and market interests was not new. More than a quarter-century before, heterodox economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen came to a similar conclusion. But rather than decry the power of the engineer over production in industrial society, he welcomed it as a great mediator.35 This “general staff of industry” as he called them would settle the dispute between capital and labor for good. This was necessary for two reasons: first, the complexity of the industrial system (very similar to Galbraith’s planning system) meant that it could no longer be run by non-experts, and second, too large a community outside of capital and labor were dependent on that system to allow one side to work toward their vested interests alone. Veblen believed that engineers could continue running the industrial system in the interests of the community as a whole, rather than from their own narrow interests. In The Engineers and the Price System, he wrote that he believed that they would soon realize their ability to oversee society for the greater good. As the role of engineers and professional experts grew exponentially in society, they were “beginning to understand that commercial expediency has nothing better to contribute to the engineer’s work than so much lag, leak, and friction.”36 Further, “they are accordingly coming to understand that the whole fabric of credit and corporation finance is a tissue of make-believe.”37

But of course, fantasy has long driven civilizations to action, even the immaterial can have objective consequences. This is what Marx meant when there was a “phantom-like objectivity” to the value of a commodity.38 While the marks of the socially necessary labor time imbued in a commodity may not be readily apparent, that it has been worked by human hands is understood. Along with that understanding, is that of a whole host of corresponding social practices that allow such an abstract principle to order human affairs. At the same time, Veblen was correct to point out that technology applied to production was constrained by the relations of production, of the need to maintain private ownership, and the corresponding profit motive, but that tension exists does not mean that it will be worked out. Particularly, if there is no revolutionary rupture with the old order of things, which he believed not only unnecessary but an unwanted obstruction to the industrial system. For him, the success of the Bolsheviks was what had simultaneously made their situation so difficult. The fact that Russia was technologically backward meant that the: “Russian community is able, at a pinch, to draw its own livelihood from its own soil by its own work, without that instant and unremitting dependence on materials and wrought goods drawn from foreign ports and distant regions.”39

In the case of an advanced industrial society like the United States, such a revolution was undesirable for the inverse reason: dependence on the industrial system meant that disrupting its function would lead to widespread deprivation and misery. Instead, Veblen believed there would eventually be a bloodless coup by engineers, after capitalists “eliminate themselves, by letting go quite involuntarily” as “the industrial situation gets beyond their control.”40 In doing so, he underestimated the lengths that capital would go in holding on to their interests and just how complex industrial society would become. The increasingly complicated division of both mental and manual meant that even a vanguard of engineers and experts could not manage the whole system alone. Eventually, this process would erode their relative independence from either the capitalist class or the working class by pulling them toward one pole or another.41

Much like Veblen, in an ironic twist of fate, Galbraith the economist came to the position that economics no longer mattered. Rather, the conquest of political power by monopolies had, and would, determine the future of American society. By separating the political from the economic, rather than view them as two sides of the same co-determined coin, he assumed that one could continuously dominate the other, rather than engage with each other in a dialectical back and forth. This view that monopolies could disembed themselves from the dictates of the market has not gone anywhere. In fact, it was central to the argument of Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski’s popular book the People’s Republic of Walmart that made the rounds across a number of different left groups and tendencies. Phillips and Rozworski present a full-throated socialist defense of planning in the People’s Republic of Walmart, highlighting the prominence of firms like Walmart and Amazon, whose very success, they argue, is predicated on their tendency to eliminate as much uncertainty as possible through complex planning systems.

The authors acknowledge that “the real world is often one of messy disequilibrium, of prices created by fiat rather than from the competitive ether,” but still “remains one where markets determine much of our economic, and thereby social life.” Unfortunately, their conception of firms as “islands of tyranny” reinforces the notion that these massive companies can remove themselves from the sea of market competition.42 To put in Marxist terms, these firms are somehow able to ignore the law of value through their application of central planning. Much like Braverman’s critique of postindustrial society as overemphasizing the growth sector of the economy, a similar criticism can be leveled at Phillips and Rozworksi for focusing too much on the ascendant firms of the twenty-first century. Amazon and Walmart may be economic juggernauts now, but no one can know what the march of history has in store for them in the long term. When Galbraith wrote the New Industrial State in 1967, he seemed very certain of the futures of Ford and GM. The same cannot be said of either from 2020. This is not to suggest that socialists should not be concerned with central planning, but rather, that planning is not a magic bullet that makes the transition away from capitalism inevitable.

Over a century ago, Lenin praised the scientific management of Taylor as a progressive force in capitalist society because of its tendency to bring order to the chaos of capitalist production. He believed that it would eventually lay the foundation for socialism through its rationalization of production and distribution within capitalism. According to Lenin, Taylorism had inadvertently helped prepare for “the time when the proletariat will take over all social production and appoint its own workers’ committees for the purpose of properly distributing and rationalizing all social labor,” and that the increasing centralization of industry on a large scale would “provide thousands of opportunities to cut by three-fourths the working time of the organized workers and make them four times better off than they are today.”43 If one looks at the universalization of Taylorism in the capitalist world and the experience of the Soviet Union, there is, at the very least, a question mark over the efficacy of taking on the methods of scientific management without a mind to the way they help structure relations of production.

The same can be said about the claims of planning. While it may have had the effect of stabilizing individual capitals, or even large segments of capital, planning has not led to the stabilization of capital in general. In other words, to assume that the means to liberate ourselves from capital exist as tools to be grasped fully-formed from the capitalist system, be it either scientific management or central planning, is to an assume the inevitability of socialism, a false proposition that Rosa Luxemburg grasped more than a hundred years ago when she appealed to the imperative toward either socialism or barbarism.

Writing during the nightmarish upheaval of total war in Europe, Luxemburg reminded the proletariat movement of their latent potential, their role as agents in history to overturn the existing order. From the standpoint of the early twenty-first century, in a world wracked by imperialist proxy wars, climate catastrophe, and political-economic uncertainty, her words echo today as true they did then when she first wrote them in 1915. In the face of this reality, “the only compensation for all the misery and all the shame would be if we learn from the war how the proletariat can seize mastery of its own destiny and escape the role of the lackey to the ruling classes.”44

What Luxemburg so masterfully illustrates with her passionate reminder of human will in shaping the course of history, is what E.H. Carr gestures toward in his methodological book What is History? His book outlines a general methodology for the history discipline. In doing so, he takes aim at critics’ contentions that historical materialism posits an inevitable outcome to history. At the same time, he challenges a view of history as random happenstance. For Carr, “nothing in history is inevitable, except in the formal sense that, for it to have happened otherwise, the antecedent causes would have had to have been different,” but at the same time, history is not completely “a chapter of accidents, a series of events determined by chance coincidences, attributable only to the most causal of causes.”45

Late Capitalism and the Law of Value

The discussion above may seem a digression from the larger analysis of the long 1970s. However, the faith that the economic question within capitalism had been solved by social democracy and that the road to peaceful transition had been charted, is what blinded many to the cracks in the postwar consensus—a belief not altogether different from that of the inevitable triumph of socialism. Today, a similar belief exists. For many, the idea that we could go back to the politics of the postwar consensus is not only feasible, but also desirable. This stems from a mistaken notion that the only thing that led to its breakdown was politics: if we can just get back to the right kind of politics, then we can make social democracy great again.

Even as he criticized the power of the corporation and the state in the modern economy, Galbraith made such an argument about politics during the breakup of the postwar order. He wrote in the Introduction to the 3rd edition of the New Industrial State released in 1978, that by all accounts the “sharp recessions” of that decade were “by wide agreement…the result of a deliberate act of policy to arrest inflation,” with “those holding most vehemently that inflation was still a natural phenomenon being those responsible for the policy.”46 While Marxist Economist and Historian Ernest Mandel would likely agree that nothing in political economy is inherently natural, this does not mean that human beings do not create systems that stand over them and cannot be controlled at will. Human beings certainly forged those bonds through the muck of ages, but that does not mean that their essence remains apparent as they become imbued with new meaning across time. This is of course what Marx meant when he employed the concept of commodity fetishism, that is to say social relations between people appear as relations between things.

Mandel’s Late Capitalism is very much a response to this overly politically-determined view of history. He provides empirical evidence to support the notion contrary to thinkers like Galbraith, Baran, and Sweezy that Marx’s critique of political economy still stood as definitive in the era of monopoly capitalism. Even the title of his work was meant as a response to those who believed capitalist society had superseded the laws of motion of capital as described by Marx in the same way that an Einsteinian universe had eclipsed the Newtonian one early in the middle of the twentieth century. For Mandel, the question of whether late capitalism represented a new stage of capitalist development could be answered by asking whether “government regulation of the economy, or the ‘power of the monopolies,’ or both, ultimately or durably cancel the workings of the law value.”47 Indeed, if that question was answered in the affirmative, then any unstable holdovers from the old order such as “crises and recessions” could “no longer… due to the forces inherent in the system but merely to the subjective mistakes or inadequate knowledge of those who ‘guide the economy.’”48

By holding Marx’s critique of political economy as valid even in the age of monopoly capital, Mandel was able to see the postwar era for what it was: the calm before the storm of capitalist crisis. An interregnum, which could lead either towards continued domination or towards the liberation of the working class. Rather than take monopoly power as something eternal, Mandel looked at its long-term historical trajectory. First, by sticking to a Marxist conception of the economy that is consistent with the labor theory of value, his starting point of analysis is that the equalization of the rate of profit as it relates to the theory of the rate of profit to fall does not imply an equal division of profits among capitalists. Rather, because this rate is determined by the “total mass of capital set in by each autonomous firm,” those firms that employ the greatest amount technology or constant capital in the production process, are able to siphon surplus from those with a below-average level of productivity, despite a smaller footprint in terms of variable capital or labor power used in the course of production.49 However, while this does not imply an equal mass of profits, there is still the tendency to push and pull the rate of profit towards a social average on the level of individual firms. Effectively, this means that the role of the monopoly in late capitalism is to prevent as long as possible the equalization process from taking place by blocking the movement of capital from one branch to another. But as with any wall, there is always a ladder that can be climbed to reach the other side.

For instance, Mandel argues that the short-term need of monopolies to bring non-monopolized sectors under their purview to control effective demand leads in the long term to an erosion of their monopoly power through an acceleration of the equalization of the rate of profit. In other words:

The more this process advances, and the nearer the package of goods produced by monopolies comes to compromise the whole range of social production, the smaller monopoly surplus-profits will tend to become and the closer the monopoly rate of profit will have to adjust to the average rate of profit. The monopolies will thus increasingly be dragged into the maelstrom of the tendency for this average rate of profit to fall.50

At the same time, even if non-monopoly sectors of the economy remain independent of the monopoly ones, in times of downturn those sectors find themselves at a diminished capacity. Therefore, the monopoly sector is not furnished with the surplus-profits that protect them from the fall in the rate of profit. Not only do monopolies in the last analysis sow the seeds for their own demise vis-à-vis their need for continual growth, but also attempts to subvert this tendency in the long term, including those of the state, have the effect of intensifying these contradictions.

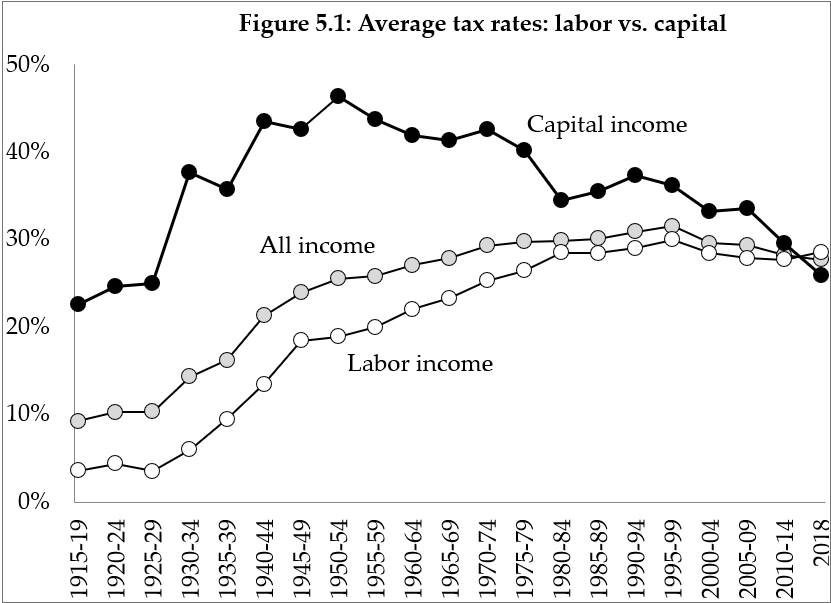

Mandel identified at least three specific limitations to state intervention into the capitalist economy. First, the stimulation of demand through the printing of new money has the effect of lowering the rate of surplus-value i.e. the rate of profit, and in no way does it ensure productive investment–that is investment in the production of value leading to the accumulation of capital. Second, if the state invests any redistributed surplus-value towards productive investment of its own, it must ensure that those investments do not directly compete with already existing sectors of the economy. Finally, if state investments made from tax revenues are to be generative of new value, rather than a redistribution of existing surplus-value, they must not be from capital itself, but from the petty bourgeoisie and the working class’ general wage fund.51 Data from Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman’s recent book the Triumph of Injustice bears out this assumption. While their definition of what constitutes wealth and the question of how to address income inequality may be flawed, their collection of average effective tax rate data is a helpful illustration of the shifting tax burden that Mandel first theorized in 1972:

This change in the composition of the tax base helps to create antagonistic relationships between the capitalists on the dole of the state and the petty bourgeoisie, as well as those segments of capital whose profit is not ensured through state subsidy. This explains the rise of the politics of the taxpayers revolt, which was and has been so central to building a base of support for the neoliberal turn.52 Mandel identifies this tension as a real limit to the support that the state can have for monopolies: the state cannot support monopolies if they endanger the capitalist system as a whole.53

Long Waves of Capitalist Development

The main point of Late Capitalism may have been to illustrate the continued validity of the Marxist research project in the face of its dismissal by critics on both the left and the right, but Mandel did not simply seek to explain the crisis of his moment. Instead, he sought to provide a long-term view of capitalist development, one that explained the tectonic shifts in the mode of production from one generation to the next, and most importantly, one that might clarify where the transition of his own time might lead.

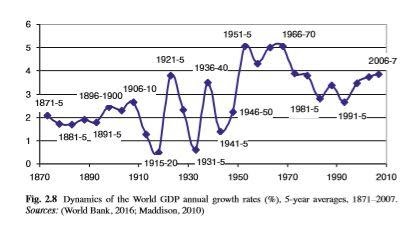

This longue durée approach to the historical development of capitalism is precisely why Mandel’s work seems so prescient in the light of the present. This perspective allowed Mandel to historicize his own moment as part of the larger development of capitalism as a global economic system counterposed to contemporaneous bourgeois economists, who held that golden age as a permanent stasis. Mandel accomplished this by adapting Soviet Economist Nikolai Kondratieff’s work on long waves of capitalist development, which posited that along with short-term business cycles there were longer-term ones that lasted for fifty years more or less. These long waves inevitably brought about a restructuring of the capitalist economy through a revolution in technology, or, to use another phrase, the development of the forces of production. In Mandel’s version, these long waves consisted of a period of twenty-five to thirty years, either expansionary or depressive in character. Despite the dichotomy of expansion and depression in Mandel’s long waves, the standard five to seven-year business cycle still operated. For example, during depressive waves recoveries are not as robust as those that occur during expansive ones.

Mandel explains the breakdown of each kind of wave and its effect on the rate of profit as follows: “expansive waves are periods in which the forces counteracting the tendency of the average rate of profit to decline operate in a strong and synchronized way,” and “depressive long waves are periods in which the forces counteracting the tendency of the rate of profit to decline are fewer, weaker, and decisively less synchronized.54This connection to rate of profit, and thus to the levels of investment, helps explain another part of Mandel’s unique interpretation of the long waves in capitalist development. He posited that, unlike business cycles, expansionary waves were by no means automatically triggered by long depressive one. In this way, he was able to integrate Leon Trotsky’s criticism of Kondratieff into the way that he applied the concept. Trotsky critiqued Kondratieff’s long cycles for removing human agency from the development of new technology and ways of working, as well as, the role played by what might be termed exogenous or outside the economic base of society such as wars and revolutions to creating conditions for a new expansionary wave.

Defending this interpretation and application of long waves to the history of capitalism against charges of eclecticism, Mandel argued that, often, the “creative destruction” needed to reinvigorate the level productive investments and trigger a new expansionary wave could actually require the physical destruction of fixed capital and of older technology, rather than just its market devaluation. Indeed, his retort, that:

it is inevitable that new long wave of stagnating trend must succeed a long wave of expansionist trend, unless of course, one is ready to assume that capital has discovered the trick of eliminating for a quarter of a century (if not for longer) the tendency of the average rate of profit to decline.55

speaks to the room that exists for “heterodoxy” within the orthodox Marxist tradition.

If nothing else, Marx continuously used the newest methods bestowed to him by the practitioners of classical political economy in critiquing them. To assume that he would not have continued to do the same had he had the opportunity to continue his project is to contradict the very nature of his work. Like Marx, Mandel’s use of long waves in no way betrays his commitment to critique of political economy, in that their abstraction is in no way opposed to the concrete. If anything it was Mandel’s critics who were idealistic in their criticism of his notion of exogenous triggers.

The 1970s as the End of an Era and the Foundation for the Neoliberal Turn

Another useful method inherited from Mandel’s adoption of the modified Kondratieff’s cycles, is the notion that these long waves could be conceptualized as unique historical moments. The postwar boom represents just one of many long expansionary waves, and the interwar years and the Great Depression represent an example of a long period of stagnation. Considering that the lectures that made up his book Long Waves were given in 1978, most of his theorization on the period of the collapse of the postwar order and the neoliberal turn remained mainly predictions based on existing evidence from the start of that wave and other speculations. Still, they do offer an insight not only into how this turn was experienced for Mandel as an individual, but also on some general assumptions and observations that can be subject to an empirical review of subsequent data.

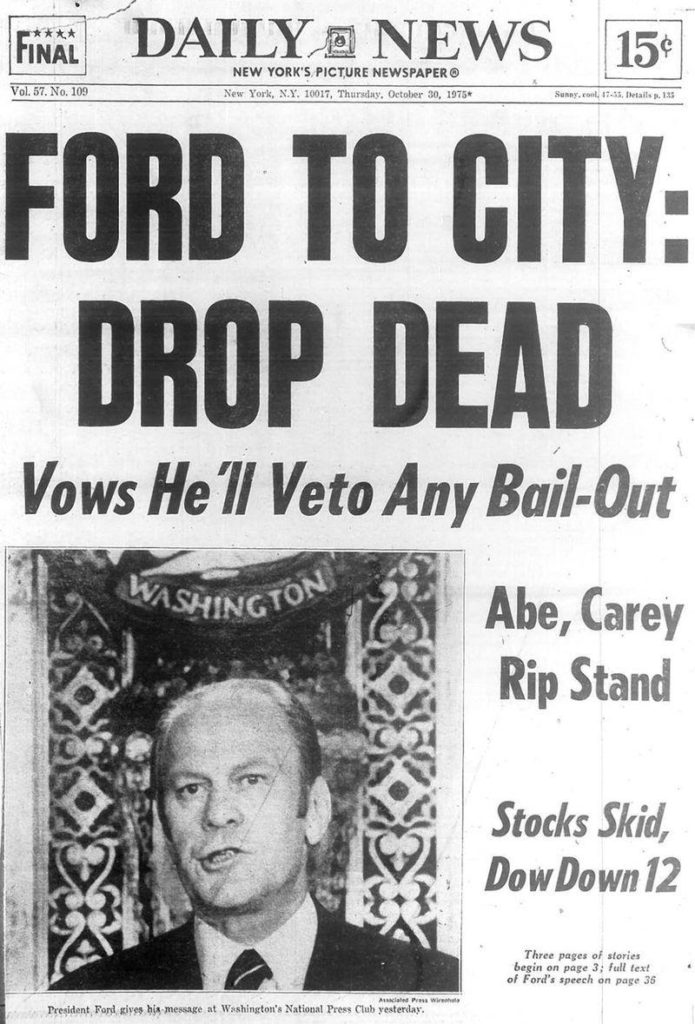

One point, in particular, seems terribly cogent, especially in the light of contemporary explanations of the neoliberal turn on the left. Mandel postulates that the shift from a certain Keynesian orthodoxy to a monetarist one at the level of national governments did not create neoliberalism, but rather, it was the political-economic crisis brought upon by the stagflation of the 1970s that made one set of ideas marginal and brought the other in vogue. Given the logic of capital and its need to restore the rate of profit, the welfare state could no longer offer the safety net it once had, and indeed it represented a barrier to further accumulation. This materialist explanation of the hegemony of the likes of Friedman and Hayek makes far more sense than the notion that somehow the strength of their ideas created a brand-new consensus by the 1980s. As Mandel writes, this “new economic wisdom” was by no means ‘scientific,’ despite claims to the contrary, but rather “corresponds to the immediate and long-term needs of the capitalist class.”56 Recent scholarship on the New York City financial crisis of 1975 that among other things, produced the now infamous headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” points to such a pragmatic and ad hoc adoption of new economic ideas in response to uncertain realities of the day.57

Fear City by Kim Phillips-Fein, tells the story of the response to the deep crisis of the city from above and below, but ultimately though, it was those who acted from above won the day. However, the idea that those crafting fiscal policy and managing the city’s budget were either contemporary Republican deficit hawks and their Third Way Democratic party handmaidens of austerity should be put to rest. Prior to the financial crisis, Phillips-Fein argues that New York City was a bastion of social democracy created by decades of militant working-class struggle. It could only have through such a crisis that those gains could have been unmade. Even those in seats of authority called to helm the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC) and the Emergency Financial Control Board (EFCB) saw themselves more in line with the liberalism of the Great Society than that of the Third Way.

The MAC was a public-benefit corporation set up to financialize the city’s assets in the face of mounting debt and the EFCB was an institution set up to oversee the city’s spending. Both institutions exemplify how the financial crisis created two political-economic functions characteristic of the emergent neoliberal state: with one hand the state privatized its assets to make up for shrinking state coffers, and with the other, took away those services deemed unnecessary to the accumulation of capital in general. In the case of men like Felix Rohaytn who helped create the MAC, it would be their experience of saving the city from itself that would transform their thought, rather than their thought transforming the city. However, we should not assume that it was unavoidable that such a view would become the hegemonic one. Indeed, it took the mythologizing of the moment by politicians like New York Mayor Ed Koch for the notion that there was no alternative to austerity for the view to take hold. Koch did so by painting the crisis as a teachable moment that allowed the city to see the error of its ways and to move on “in a positive direction.”58

Aside from explaining the formation of the new dominant bourgeois ideology of late capitalism, Mandel also described the actions that would be necessary to restore the rate of profit during the depressive wave that began in 1973, signaled by the oil shocks of that year. He predicted that in order to lay the foundation for a restored rate of profit which would eventually give way from a stagnating wave to an expansionist one, there would need to be a disciplining of organized labor through the use of unemployment. This would simultaneously allow capital to increase the level of exploitation through a degradation of conditions and circumstances of work, the further concentration and centralization of capital, which would lead to reduced cost in means of production like equipment, raw materials, and energy—and most importantly “massive applications of new technological innovations” and “a new revolutionary acceleration of in the rate of turnover of capital.”59

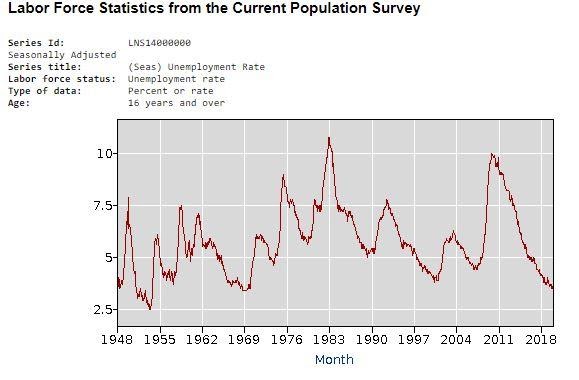

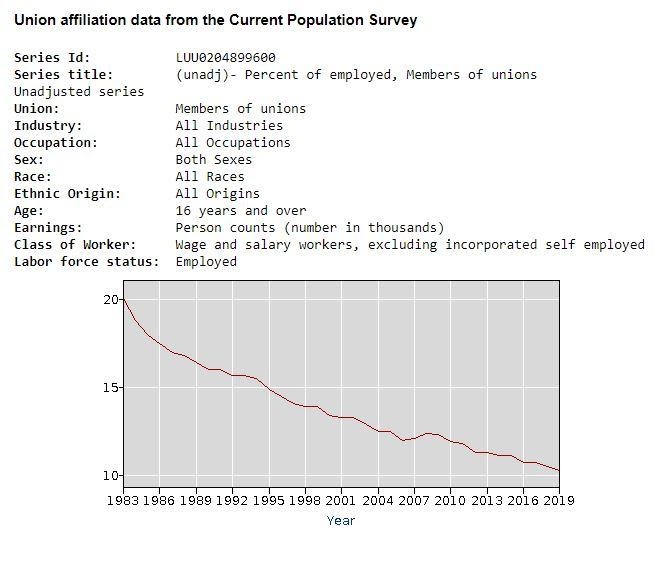

Taking up Mandel’s point about the necessity of unemployment to weaken labor organizations, it is no accident of history that from the mid-1970s forward the rate of unemployment never reached the consistent lows of the preceding periods, at least until the precipice of the current century. Nor does it appear to be a coincidence the same period saw a massive dip in levels of unionization as unemployment grew. While this development was by no means inevitable, and was most certainly did not come to pass without resistance, the necessary preconditions for the neoliberal subject were forged through this moment. There was “no alternative,” not because Reagan and Thatcher said so, but because attempts to move beyond the New Deal and the Great Society had become stalled and the material preconditions for the working class to fight in their own name were increasingly closed off from them. The experience of that process for working people and their institutions will be picked up below.

Keeping in mind the fact that expansionary waves are not an unavoidable exit from a depressive one, Mandel highlights a certain point about the expansion of the world market that warrants close inspection. He argues that “one should not confuse an overall expansion in the world market at a rapid pace with an overall restructuring of the international division of labor.” That is, “employment at lower wages in certain countries is substituted for employment at higher wages in other countries,” and “equipment [being] shifted from one part of the world to another” at best leads to a marginal increase in effective demand through lowered operating costs, but this is not enough on its own to engender “a new long-term wave of accelerated growth.”60

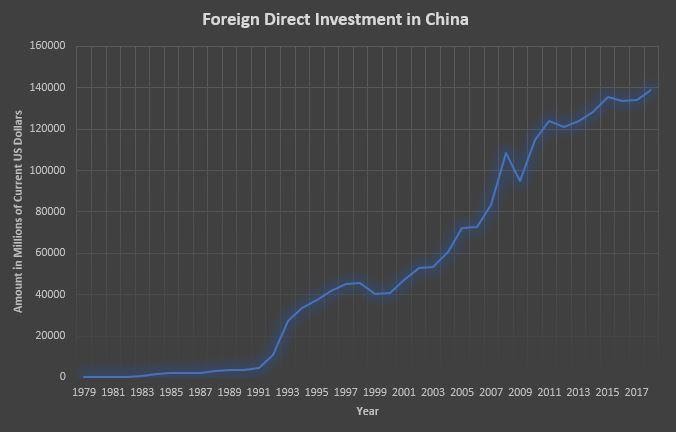

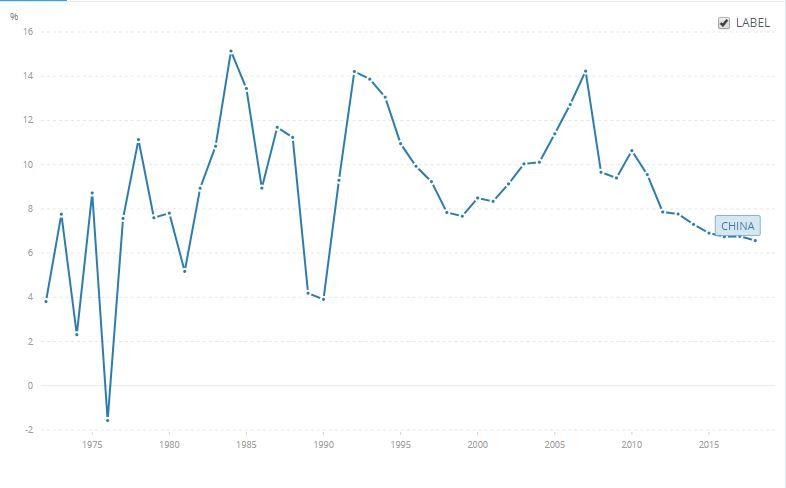

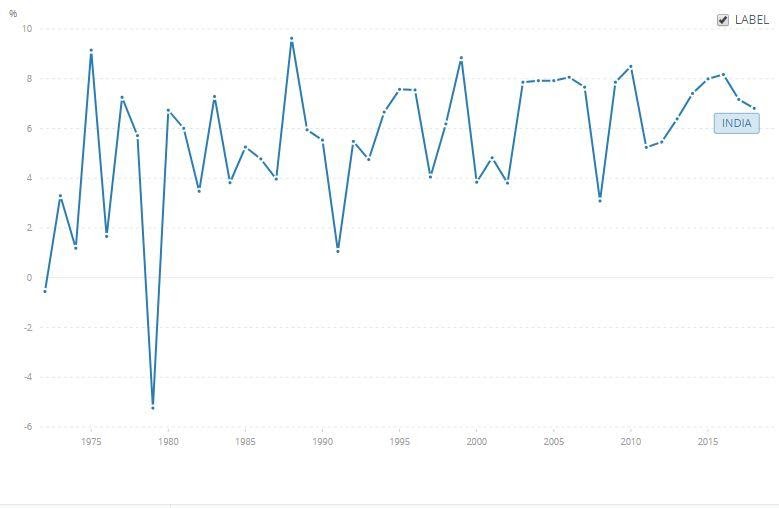

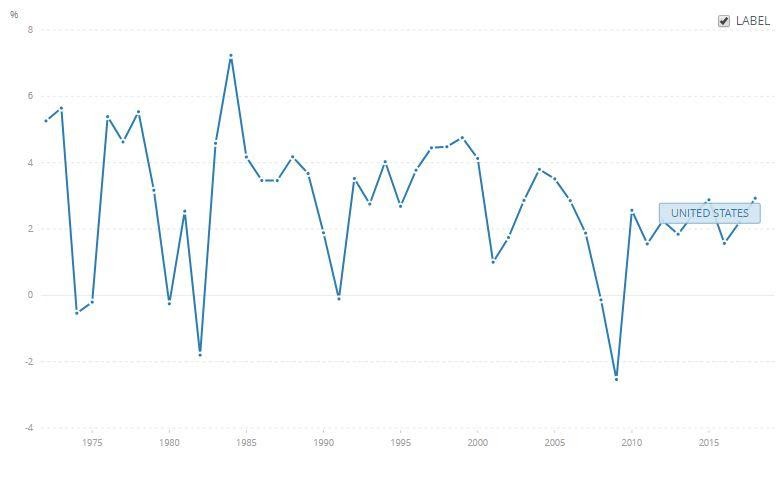

Neoliberalism as a political project is often spoken of as going hand in hand with globalization. In other words, in order to return to an era of fiercer capitalist competition, barriers to trade between nations needed to be overcome, either by trade agreement or military coup. Except, rather than completely transforming the international division of labor, for a time neoliberalism amounted to tinkering around its edges. Meaning that, what is thought of as the rapid development of countries like China and India did not occur as rapidly as is often assumed. It took decades to move from countries which provided raw materials to components of manufactured products to countries that finished goods themselves. It took years of reinvestment in themselves before their economies could stand on their own two feet. Looking at levels of foreign direct investment as an indicator of multi-national development of national economies, it seems clear that it took years before even the levels of investment in formerly colonized countries began to approach those of the dominant economic player of the twentieth century: The United States. Despite these changes, following decades of infrastructural neglect, catalyzed by the devaluation and privatization of the Great Recession, the U.S. once again became a haven for foreign investment in the 21st century.

This data on foreign direct investment taken alongside GDP growth makes clear that rather than completely transforming relations between the United States and the developing world, FDI reified the existing order of things. Of course, this does not mean that nothing changed between 1973 and 2008, but instead that it took the deepening of the long-term crisis of capitalism (more accurately described as malaise or stagnation) for this incremental process of capitalist realignment to achieve a qualitative shift from a quantitative one.

The only thing that kept the machine of capital in motion was the industrialization of the developing world as a means of propping up advanced industrial economies. What this means is that despite the massive economic growth across the last 40 years, these developing economies were still relegated to junior partners of American and European firms due to the need to attract the investment needed to develop their productive forces in order to compete with the level of productivity of those companies. This means that they still played their historical role of furnishing raw materials and later cheap manufactured goods to advanced industrial economies, which in return provided capital goods, means of transport, and management methods.

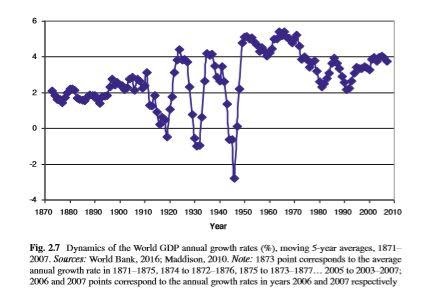

When all of this is taken into account, a picture emerges of a unique phenomenon: what might be called a stagnating expansionary wave. In a word, while there was a recovery from the prior lows, it never matched that of the previous cycles. This is where Mandel’s notion of non-self-sustaining cycles can be of some use. Without the massive “creative destruction” of worldwide warfare or a global catastrophe, and the continued application of Keynesian monetary policy without its commitment to demand stimulating fiscal policy, the conditions created could only partially restore the rate of profit following the crisis of the 1970s. This analysis fits with some recent scholarship of Kondratieff waves or K-waves, particularly those working within the world systems tradition. While three such practitioners: Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch, argue that the period from the 1970s forward is not out of line with the long-term historical trajectory of K-Wave cycles, they, at the very least, seem to see its effect on the core/periphery dynamics within the world market.

They characterize the period from 1968/74 to 1984/91, or what they term Phase B of the Fourth K-Wave in the history of capitalism, as a moment in which:

The Core was ‘attacked’ by the Periphery economically—first of all through a radical increase in oil and some other raw material prices. In the meantime, the West invested rather actively in the Periphery (especially, through loans to the developing countries).61

At the same time, the following period, or Phase A of the Fifth K-Wave (1984/91 to 2006/08), saw the centers of growth slowly shift from the traditional Core to the Periphery. In other words, economic development moved from the First to the Third World, from developed to the developing world. On a purely economic level, they assert that this period represents red in the ledger for the core and black for the periphery, which of course leaves out so many of the social realities that sustained these processes, but that problem has already been addressed by countless thinkers and needs not be relitigated here.62 What is important for the moment is their preoccupation with a mechanically-determined system change, in both the literal technological sense and an economic one, a framework for understanding long waves that both Trotsky and later Mandel criticized as removing human agency from the equation of world history.

Staking a claim against those that see the period from the 1970s on as one of “decelerating scientific and technological progress,” they contend that the further development and generalization of new technology is a product of the need for the periphery to catch up to the level of development of the core.63 That is, the further accelerated development of the core over the periphery would risk a fracturing of an integrated world system, and to be charitable, they do account for the necessity of “structural changes in political and social spheres” for “promoting their synergy and wide implementation in the world of business.”64 However, from this perspective, it seems the capitalist and international state system bends to fit the needs of developing technology, rather than vice versa. If it is assumed that humanity has created a machine too big to control, then such a view makes sense. However, if we still believe that the technology we build and the economic system we live within is capable of being transformed through our own force of will, then it is imperative that such a view be rejected.

Indeed, a general proliferation of advanced technology on a global scale, at least that imagined in their work, would require the transcendence of capitalism. As Mandel wrote in Late Capitalism, there are real limitations on the professionalization of the workforce and the automation of labor, as those movements tend to diminish the total amount of surplus-value being produced by reducing the number of workers employed by capital, at the same time that they transform the mental and manual separation of labor—a division that ensures discipline and hierarchy among the working class. To brush up against those limits is to go against the drive toward “self-preservation.”65

Grinin, Korotavev, and Tausch may not see the new economic order that rose from the ashes of the postwar compact during the 1970s as outside the ordinary pattern of long wave cycles. However, their own data does seem to point to a newly emergent pattern of development, one that vindicates the Mandelian notion of expansionary long waves as often contingent upon exogenous triggers to restore the rate of profit. On the surface, this seems to lend credence to the idea of stagnating expansionary waves outlined above, but it would take more than the work examined so far to legitimate these waves as a category of analysis.

The 1970s and the Failure of Capitalist Production

Marxian economist Andrew Kliman’s work on the rate of profit and the underlying causes of the Great Recession helps to bridge the gap between the work of Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch and Mandel. At the same time, it makes the existence of stagnating expansionary waves not only seem likely, but also the most probable explanation for the movement of capitalist development over the last half-century. This work, The Failure of Capitalist Production, is fairly straightforward in its line of argumentation. There is very little in the way of literary frills or flourishes that a historian might like to see in his attempt to correct what he calls the “conventional left account” of neoliberalism. Regardless of form, its content empirically validates what had only been examined previously through tangential bourgeois economic measure: the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Marxist economists like Mandel used measurements like GDP, CPI, and Industrial Capacity Usage as stand-ins for actually measuring the rate of profit, among other things, to grasp through darkness towards answers—to see beyond the form of appearance. For instance, a lag in GDP growth might point to a lag in new productive investment or low Industrial Capacity Usage might point to a lack of incentive to invest productively, but Kliman does something different with his book. Applying the temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI) of Marx’s value theory, he uses the extensive U.S. economic data to measure fluctuations in the rate of profit.66

In doing so Kliman finds that, in contrast to what more traditional accounts have argued, the discipline of labor and the shift in advanced industrial economies away from manufacturing to service and finance did not produce an upswing in the rate of profit. Instead, he shows this to be on the whole a failed fix to increase productive investment, due to the unwillingness on the part of policymakers to unleash the destructive potential of an untethered capital upon the world. The fear of what a crisis as deep as the Great Depression would do to the system as a whole acted as a failsafe against a pure market fundamentalism. To unchain the latent extirpative force would be folly, as it represents an existential gambit on the part of capital on whether it would survive the destruction intact or if it would be felled by the gravediggers it might produce.

Ultimately, this double-bind creates conditions in which “artificial government stimulus…produces unsustainable growth” that “threatens to make the next crisis worse when it comes,” and all for nothing, as “the economy will remain sluggish unless and until profitability is restored”—that is unless the character of production changes.67 From this perspective, what could be termed neoliberalism did not begin in the 1980s, but rather, was born out of the beginning of a “long period of relative stagnation” that began in the 1970s.68 The Reagan Revolution and Voodoo Economics were themselves a means of saving the system from itself without recourse to Pascal’s wager of pure creative destruction, and not the crucible of economic transformation themselves.

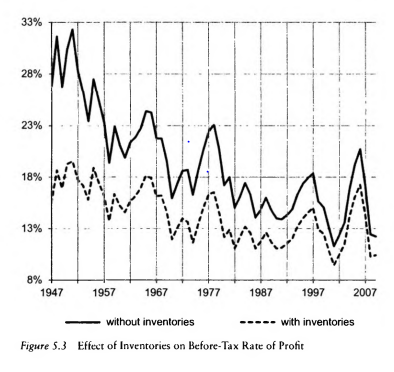

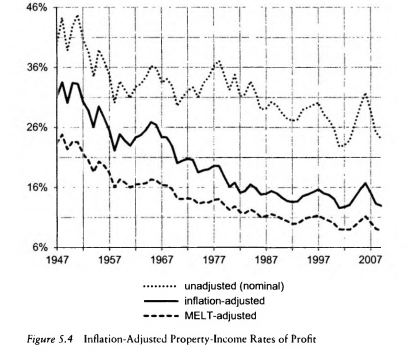

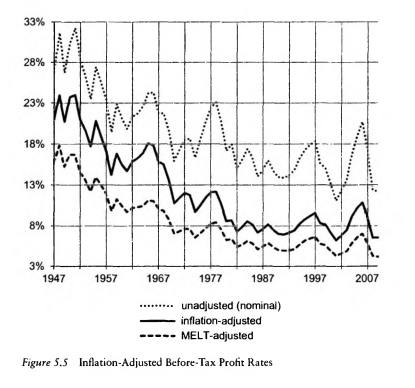

Kliman pulls from two data sets to measure the rate or profit in the United States: the first, before tax-profits; and the second, what he describes as the “property-income” rate of profit. The second data in his estimation is closer to the spirit of Marx—in that it “counts as profit all of the output (net value added) of corporations that their employees do not receive,” including “money spent to make interest payments and transfer payments (fines, court settlements, gift contributions, and so on, to pay sales and property taxes, and other minor items.”69 Such an approximation of the Marixan rate of profit makes sense, when we consider that Marx wrote in the second volume of Capital that it is:“immaterial for the rent collector of a landlord or the porter at a bank that their labor does not add one iota of value of the rent, nor to gold pieces carried to another bank by the sackful.” Rather, all that mattered was that they received a portion of value produced from the point of view of the total social production.70 Kliman demonstrates this historical decline in the rate of profit by applying various methods of control to both data sets in different ways. For instance, including inventories in the before-tax rate as a way to factor in the importance of turnover or adjusting for inflation, among other methods.71

All of this serves to illustrate the economic stagnation of the last fifty years, the collective process of kicking the can down the road on the part of the bourgeoisie and their representatives in the bourgeois state. Both wings of neoliberalism failed to address the problem of the falling rate of profit and instead papered over the contradiction with a series of stopgaps that have ultimately made capitalism more unstable, and not less. However, to just understand the economics and not the accompanying social realities are to do a disservice to the Marxist project. Knowing the problem, on the other hand, better shapes the line of inquiry into the historical experience of working people and how they have reacted to and shaped the unfolding of historical processes.

Working from Fordism to Neoliberalism

Before dissecting the economic basis of the emergent neoliberal era, this essay sought to illuminate the difficulty in which those writing at the time of breakdown of the postwar order had in seeing that the systems built through the crises of the 1930s and 1940s struggle under the strain of globalization. For many, collapse appeared as a bump in the road, one that could simply be smoothed over. But as the expansionary wave of the postwar boom gave way to the stagnating depressive wave in the middle of the 1970s, the possibility of simply repaving the same road became untenable. The ability to maintain an adequate rate of profit and the truce between capital and labor became a pressing contradiction that had to be resolved one way or another. In the end, it was capital that won the battle over who would determine the future, but not without struggle.